Statutory Acknowledgements in Northland October 2018 Version Reason for Release Overview of Changes Date by Who

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

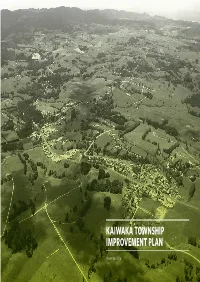

Kaiwaka Township Improvement Plan

KAIWAKA TOWNSHIP IMPROVEMENT PLAN November 2016 Acknowledgements Authors: Sue Hodge – Parks and Community Manager – Kaipara District Council Annie van der Plas – Community Planner – Kaipara District Council Sarah Ho – Senior Planning Advisor – NZ Transport Agency Brian Rainford – Principal Traffic and Safety Engineer – NZ Transport Agency Mark Newsome – Safety Engineer – NZ Transport Agency Production and Graphics: Yoko Tanaka – Associate Principal / Landscape Architect – Boffa Miskell Special thanks: Derek Christensen, Ruth Tidemann and all of Kaiwaka Can Taumata Council Robbie Sarich – Te Uri o Hau Liz and Rangi Michelson – Te Uri o Hau Ben Hita – Te Uri o Hau Martha Nathan - Te Uri o Hau Henri Van Zyl – Kaipara District Council Jim Sephton – NZTA Sebastian Reed – NZTA The wider Kaiwaka Community who have provided feedback into this plan NZ Police If you have any further queries, please contact: Kaipara District Council NZ Transport Agency Private Bag 1001, Dargaville 0340 Private Bag 106602, Auckland 1143 T: 0800 727 059 T: 09 969 9800 www.kaipara.govt.nz www.nzta.govt.nz CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION 2 2. CONTEXT 4 2.1 HISTORY 2.2 THE KAIWAKA TOWNSHIP TODAY 2.3 STATE HIGHWAY 1 (SH 1) 3. VISION FOR KAIWAKA 6 4. COMMUNITY ISSUES & DISCUSSION 7 TABLE 1. COMMUNITY ISSUES AND DISCUSSION 5. STRATEGY AND IMPROVEMENTS 14 TABLE 2: IMPROVEMENTS TO ACHIEVE VISION MAP 1: EXISTING CONTEXT PLAN MAP 2: IMPROVEMENT PLAN - WIDER TOWNSHIP AREA, SHORT TO MEDIUM TERM (1-5 YEARS, 2016 -2021) MAP 3: TOWNSHIP IMPROVEMENT PLAN - MAIN TOWNSHIP, SHORT TO MEDIUM TERM (1-5 YEARS, 2016-2021) MAP 4: TOWNSHIP IMPROVEMENT PLAN - MAIN TOWNSHIP, LONG TERM PLAN (5 YEARS+, 2021 ONWARDS) 6. -

Agenda of Kaikohe-Hokianga Community Board Meeting

KAIKOHE-HOKIANGA COMMUNITY BOARD Waima Wesleyan Mission Station 1858 by John Kinder AGENDA Kaikohe-Hokianga Community Board Meeting Wednesday, 4 August, 2021 Time: 10.30 am Location: Council Chamber Memorial Avenue Kaikohe Membership: Member Mike Edmonds - Chairperson Member Emma Davis – Deputy Chairperson Member Laurie Byers Member Kelly van Gaalen Member Alan Hessell Member Moko Tepania Member Louis Toorenburg Member John Vujcich Far North District Council Kaikohe-Hokianga Community Board Meeting Agenda 4 August 2021 The Local Government Act 2002 states the role of a Community Board is to: (a) Represent, and act as an advocate for, the interests of its community. (b) Consider and report on all matters referred to it by the territorial authority, or any matter of interest or concern to the community board. (c) Maintain an overview of services provided by the territorial authority within the community. (d) Prepare an annual submission to the territorial authority for expenditure within the community. (e) Communicate with community organisations and special interest groups within the community. (f) Undertake any other responsibilities that are delegated to it by the territorial authority Council Delegations to Community Boards - January 2013 The "civic amenities" referred to in these delegations include the following Council activities: • Amenity lighting • Cemeteries • Drainage (does not include reticulated storm water systems) • Footpaths/cycle ways and walkways. • Public toilets • Reserves • Halls • Swimming pools • Town litter • Town beautification and maintenance • Street furniture including public information signage. • Street/public Art. • Trees on Council land • Off road public car parks. • Lindvart Park – a Kaikohe-Hokianga Community Board civic amenity. Exclusions: From time to time Council may consider some activities and assets as having district wide significance and these will remain the responsibility of Council. -

Kaihu Valley and the Ripiro West Coast to South Hokianga

~ 1 ~ KAIHU THE DISTRICT NORTH RIPIRO WEST COAST SOUTH HOKIANGA HISTORY AND LEGEND REFERENCE JOURNAL FOUR EARLY CHARACTERS PART ONE 1700-1900 THOSE WHO STAYED AND THOSE WHO PASSED THROUGH Much has been written by past historians about the past and current commercial aspects of the Kaipara, Kaihu Valley and the Hokianga districts based mostly about the mighty Kauri tree for its timber and gum but it would appear there has not been a lot recorded about the “Characters” who made up these districts. I hope to, through the following pages make a small contribution to the remembrance of some of those main characters and so if by chance I miss out on anybody that should have been noted then I do apologise to the reader. I AM FROM ALL THOSE WHO HAVE COME BEFORE AND THOSE STILL TO COME THEY ARE ME AND I AM THEM ~ 2 ~ CHAPTERS CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY CHARACTERS NAME YEAR PLACE PAGE Toa 1700 Waipoua 5 Eruera Patuone 1769 Northland 14 Te Waenga 1800 South Hokianga 17 Pokaia 1805 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 30 Murupaenga 1806 South Hokianga – Ripiro Coast 32 Kawiti Te Ruki 1807 Ahikiwi – Ripiro Coast 35 Hongi Hika 1807 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 40 Taoho 1807 Kaipara – Kaihu Valley 44 Te Kaha-Te Kairua 1808 Ripiro Coast 48 Joseph Clarke 1820 Ripiro Coast 49 Samuel Marsden 1820 Ripiro Coast 53 John Kent 1820 South Hokianga 56 Jack John Marmon 1820 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 58 Parore Te Awha 1821 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 64 John Martin 1827 South Hokianga 75 Moetara 1830 South Hokianga - Waipoua 115 Joel Polack -

Kaiwaka and Kaipara District Council Working in Partnership Action Plan

Kaiwaka and Kaipara District Council Working in Partnership Action Plan Update 4 February 2016 Issue Update Crossing State Highway 1 is dangerous ONGOING PROJECT Oneriri Road intersection – what is the plan? Council is working with the New Zealand Transport Agency and community group Kaiwaka Can in Speeds along State Highway 1 and within the regards to improving State Highway 1 for local use. 70km-100km zone are too high This is focussing on a range of factors, including speeds through the township, and ensuring the town is accessible for all users – not just cars. This is an ongoing process and initial ideas were made available to the wider Kaiwaka community to feedback on in December 2015. Further opportunity for the Kaiwaka Community to provide input will be made available as this project progresses. Gibbons Road: The one way bridge outside the COMPLETE quarry has huge potholes either side, and is The eastern side of the bridge has been sealed to dangerous for those who do not know they are ensure the runoff will not sit on the surface, and there. The school bus has to stop to move around therefore reduce the occurrence of potholes here. these safely. The west side will not be sealed due to heavy traffic from lime work vehicles, as the presence of lime on the surface of the seal makes it slippery. On the Settlement Road and Tawa Road COMMUNITY INPUT REQUIRED intersection is a school bus pick up point. There Council’s Roading Engineer has visited the area, have been a number of accidents here with and was unable to see the site of concern. -

Mahinepua Peninsula Historic Heritage Assessment 2011

Mahinepua Peninsula Historic Heritage Assessment Bay of Islands Area Office Melina Goddard 2011 Mahinepua Peninsula: Historic Heritage Assessment Melina Goddard, DoC, Bay of Islands Area Office 2011 Cover image: Mahinepua Peninsula facing north east. The two peaks have P04/ to the front and P04/55 in the background. K. Upperton DoC Peer-reviewed by: Joan Maingay and Andrew Blanshard Publication information © Copyright New Zealand Department of Conservation (web pdf # needed) In the interest of forest conservation, DOC Science Publishing supports paperless electronic publishing. 2 Contents Site overview 5 Prehistoric description 5 Historic description 6 Fabric description 7 Cultural connections 10 National context 10 Prehistoric and historic significance 11 Fabric significance 11 Cultural significance 12 Management recommendations 12 Management chronology 12 Management documentation 13 Sources 13 Appendix: site record forms Endnotes Image: taken from pa site P04/55 facing west towards Stephenson Island 3 Figure 1: Location of Mahinepua Peninsula in the Whangaroa region Site overview Mahinepua Peninsula is located on the east coast of Northland in the Northern Bay of Islands, approximately 8km east of the Whangaroa Harbour. The peninsula has panoramic views of Stephenson Island to the west and the Cavalli Islands to the east. Mahinepua was gazetted as a scenic reserve in 1978 and there is a 2.5km public access track that runs to the end of the peninsula. It is located within a rich prehistoric and historic region and has 14 recorded archaeological -

21 Designations Importance

CHAPTER 21 - DESIGNATIONS Issues, Objectives and Policies within each Chapter of the Plan are presented in no particular order of 21 Designations importance. 21.1 Introduction Designations are a tool which enables Requiring Authorities approved under the Resource Management Designations Act 1991 to designate areas of land for a public work or network utility. A Requiring Authority can be a providing for public Minister of the Crown, a local authority or a network utility operator approved as a Requiring Authority under works in the Section 167 of the Resource Management Act. District 21.4 Designation Rules A Designation is a form of ‘spot zoning’ over a site or route in a District Plan. The ‘spot zoning’ authorises the Requiring Authority’s work or project on the site or route without the need for a Land Use Consent from 21.4.1 Permitted Activities the Council. A Designation enables a Requiring Authority to undertake the works within the designated The following activities shall be Permitted Activities under this Chapter: area in accordance with the Designation, the usual provisions of the District Plan do not apply to the designated site. The types of activities that can be designated include transport corridors, sewerage a) Any Activity complying with the Performance Standards set out in Section 21.5 of this Chapter. treatment plants, water reservoirs and schools. 21.4.2 Restricted Discretionary Activities Appendix 21.1 to this Chapter provides a schedule of Designations in the District. This schedule includes The following activities shall be Restricted Discretionary Activities under this Chapter: the associated Requiring Authority of the designated the land and the underlying zoning of the land parcel and its specific location within Part E – Maps (Map Series 2). -

Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand

A supplementary finding-aid to the archives relating to Maori Schools held in the Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand MAORI SCHOOL RECORDS, 1879-1969 Archives New Zealand Auckland holds records relating to approximately 449 Maori Schools, which were transferred by the Department of Education. These schools cover the whole of New Zealand. In 1969 the Maori Schools were integrated into the State System. Since then some of the former Maori schools have transferred their records to Archives New Zealand Auckland. Building and Site Files (series 1001) For most schools we hold a Building and Site file. These usually give information on: • the acquisition of land, specifications for the school or teacher’s residence, sometimes a plan. • letters and petitions to the Education Department requesting a school, providing lists of families’ names and ages of children in the local community who would attend a school. (Sometimes the school was never built, or it was some years before the Department agreed to the establishment of a school in the area). The files may also contain other information such as: • initial Inspector’s reports on the pupils and the teacher, and standard of buildings and grounds; • correspondence from the teachers, Education Department and members of the school committee or community; • pre-1920 lists of students’ names may be included. There are no Building and Site files for Church/private Maori schools as those organisations usually erected, paid for and maintained the buildings themselves. Admission Registers (series 1004) provide details such as: - Name of pupil - Date enrolled - Date of birth - Name of parent or guardian - Address - Previous school attended - Years/classes attended - Last date of attendance - Next school or destination Attendance Returns (series 1001 and 1006) provide: - Name of pupil - Age in years and months - Sometimes number of days attended at time of Return Log Books (series 1003) Written by the Head Teacher/Sole Teacher this daily diary includes important events and various activities held at the school. -

Photo Courtesy of Tony Foster

Photo courtesy of Tony Foster WHANGAROA COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2011- 2036 STAGE 1 – DRAFT PLAN FOR CONSULTATION 2 WHANGAROA COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD P ages 4- 5 OUR VISION STATEMENT Page 6 A PROFILE OF WHANGAROA Pages 7- 9 KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS Page 10 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT GOALS INTRODUCTION Page 11 1. THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Pages 12- 13 2. THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT Pages 14 - 1 7 3. THE PEOPLE Pages 18- 21 4. CULTURAL GOALS Pages 22- 25 5. ECONOMIC GOALS a) FARMING & FORESTRY Page 27- 29 b) FISHING & AQUACULTURE Page 30- 31 c) INITIATIVES & EVENTS Page 32- 33 d) TOURISM Page 34- 35 e) ARTISANSHIP Page 36 APPENDIX DEMOGRAPHICS 1. MAPS Page 37 2. LOCAL STATISTICS Pages 38- 39 3. DEVELOPMENT PROFILE Pages 40- 42 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Page 43 3 FOREWORD THE PURPOSE & VALUE OF THE WHANGAROA COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN The Whangaroa Community Development Plan (WCDP) has come about because a small group of residents expressed their concerns for the harbour and its surrounding environment to the Far North District Council, and talked of the need for an “integrated catchment management plan”. The Far North District Council’s response was to offer the community the opportunity of creating a Community Development Plan which included the concepts of catchment integration and sustainable management. A Community Development Plan is a document created by a community. It is an expression of the community’s vision and aspirations for their land, waters and people for the medium-term future. As such, it firstly has to seek those visions and aspirations. In the case of this plan, that work took place in a series of public meetings held through 2009. -

First Years at Hokianga 1827 – 1836

First Years at Hokianga 1827-1836 by Rev.C.H.Laws FIRST YEARS AT HOKIANGA 1827 – 1836 In a previous brochure, entitled "Toil and Adversity at Whangaroa," the story of the Methodist Mission to New Zealand is told from its initiation in 1823 to its disruption and the enforced flight of the missionaries in 1827. After a brief stay with members of the Anglican Mission at the Bay of Islands the Methodist party sailed for Sydney in the whaler "Sisters" on January 28th, 1827, arriving at their destination on February 9th. It consisted of Nathaniel Turner and Mrs. Turner, with their three children, John Hobbs, James Stack and Mr. and Mrs. Luke Wade, and they took with them a Maori girl and two native lads. William White had left Whangaroa for England on September 19th, 1825, and at the time of the flight had not returned. The catastrophe to the Mission was complete. The buildings had been burned to the ground, the live stock killed; books and records destroyed, and the property of the Mission now consisted only of a few articles in store in Sydney which had not been forwarded to New Zealand. Wesley Historical Society (NZ) Publication #4(2) 1943 Page 1 First Years at Hokianga 1827-1836 by Rev.C.H.Laws Chapter I The departure of the Mission party for Sydney is seen, as we look back upon it, to have been the right course. Sydney was their headquarters, they were a large party and could not expect to stay indefinitely with their Anglican friends, and it could not be foreseen when they would be able to re-establish the work. -

The Bible's Early Journey in NZ

The Bible’s Early Journey in New Zealand THE ARRIVAL It was so difficult in fact, that six years later Johnson was joined by an assistant. The Reverend Samuel Marsden, Towards the end of the 18th century, with the loss of later to be remembered by history as the Apostle to America’s 13 colonies in the American Revolution, Britain New Zealand, was studying at Cambridge University looked towards Asia, Africa and the Pacific to expand when he was convinced through the influence of William its empire. With Britain’s overburdened penal system, Wilberforce to become assistant chaplain to the penal expanding the empire into the newly discovered eastern colony at Port Jackson (by this time the original penal coast of Australia through the establishment of a penal colony settlement at Botany Bay had been moved). colony seemed like a decent solution. So, in 1787, six Marsden jumped at the chance to put his faith into transport ships with 775 convicts set sail for Botany Bay, practice and boarded a ship bound for Australia. He later to be renamed Sydney. arrived in Port Jackson with his wife in 1794. Thanks to the last minute intervention of philanthropist Marsden established his house at Parramatta just John Thornton and Member of Parliament William outside the main settlement at Port Jackson. There Wilberforce, a chaplain was included on one of the he oversaw his 100 acre farm as well as consenting ships. The Reverend Richard Johnson was given the to serve as a magistrate and as superintendent of unenviable task of being God’s representative in this government affairs. -

Book, 1789-92

~ 1 ~ KAIHU THE DISTRICT RIPIRO WEST COAST SOUTH HOKIANGA HISTORY REFERENCE JOURNAL THREE THE COUPLING OF CULTURES PHOTO BELOW SALT AND PEPPER A SPRINKLING OF MAORI AND EUROPEAN CHILDREN AT THE KAIHU SCHOOL ~ 2 ~ CHAPTERS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 6 PAGE 5 FOY FAMILY PAGE 149 CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 7 SNOWDEN-PATUAWA-FLAVELL- Foy-Sherman SHERMAN FAMILY PAGE 154 PAGE 6 CHAPTER 8 CHAPTER 2 WHITEHEAD AND BAKER FAMILY SNOWDEN-FAMILY HISTORY PAGE 178 PAGE 10 CHAPTER 9 CHAPTER 3 ARTHUR MOLD SNOWDEN-PATUAWA/NATHAN CONNECTION PAGE 194 PAGE 38 CHAPTER 10 CHAPTER 4 NEW ZEALAND - SOUTH AFRICAN WAR NETANA PATUAWA PAGE 212 PAGE 43 CHAPTER 5 SOURCES/BIBLIOGRAPHY FLAVELL FAMILY PAGE 219 PAGE 142 ~ 3 ~ Note: Intermarriage between Maori and Pakeha has been common from the early days of European settlement in New Zealand. The very early government’s encouraged intermarriage, which was seen as a means of ‘civilizing’ Maori. However, some people did disapprove of the ‘Coupling of Cultures’ 1 1 FULL STORY BY ANGELA WANHALLA MAIN IMAGE: MERE AND ALEXANDER COWAN WITH BABY PITA, 1870 ~ 4 ~ NOTE: WHANAU=FAMILY HAPU=CLAN IWI=TRIBE TAUA=WAR PARTY ARIKI=LEADER/CHIEF AOTEA OR NEW ZEALAND WHAPU/KAIHU=DARGAVILLE WHAKATEHAUA=MAUNGANUI BLUFF OPANAKI=MODERN DAY KAIHU It is my wish to have all of my ‘history research journals’ available to all learning centres of Northland with the hope that current and future generations will be able to easily find historical knowledge of the Kaihu River Valley, the Northern Ripiro West Coast and South West Hokianga. BELOW: COMPUTER DRAWN MAP SHOWING THE PLACE NAMES BETWEEN MANGAWHARE AND SOUTH HOKIANGA ~ 5 ~ INTRODUCTION Note: These following characters or families give a fine example of the connection between Polynesian and European people of the North and also their connection to the Hokianga, Kaihu River Valley and North Kaipara districts where some became prominent families of the Kaihu Valley. -

Natural Areas of Aupouri Ecological District

5. Summary and conclusions The Protected Natural Areas network in the Aupouri Ecological District is summarised in Table 1. Including the area of the three harbours, approximately 26.5% of the natural areas of the Aupouri Ecological District are formally protected, which is equivalent to about 9% of the total area of the Ecological District. Excluding the three harbours, approximately 48% of the natural areas of the Aupouri Ecological District are formally protected, which is equivalent to about 10.7% of the total area of the Ecological District. Protected areas are made up primarily of Te Paki Dunes, Te Arai dunelands, East Beach, Kaimaumau, Lake Ohia, and Tokerau Beach. A list of ecological units recorded in the Aupouri Ecological District and their current protection status is set out in Table 2 (page 300), and a summary of the site evaluations is given in Table 3 (page 328). TABLE 1. PROTECTED NATURAL AREA NETWORK IN THE AUPOURI ECOLOGICAL DISTRICT (areas in ha). Key: CC = Conservation Covenant; QEII = Queen Elizabeth II National Trust covenant; SL = Stewardship Land; SR = Scenic Reserve; EA = Ecological Area; WMR = Wildlife Management Reserve; ScR = Scientific Reserve; RR = Recreation Reserve; MS = Marginal Strip; NR = Nature Reserve; HR = Historic Reserve; FNDC = Far North District Council Reserve; RFBPS = Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society Site Survey Status Total Total no. CC QEII SL SR EA WMR ScR RR MS NR HR FNDC RFBPS prot. site area area Te Paki Dunes N02/013 1871 1871 1936 Te Paki Stream N02/014 41.5 41.5 43 Parengarenga