A Wholeperson Model of Care for Persistent Pain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Party Leadership Program 27Th – 31St May 2013

centre for democratic institutions Political Party Leadership Program 27th – 31st May 2013 Drawing Room, University House The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT As part of our contribution to the development of good political leadership and robust, accountable and democratic institutions in Melanesia, the Political Party Leadership Program (PPLP) is a peer-to-peer dialogue designed to encourage participants to: better understand the contribution that political parties can make to democracy and good governance; better understand political party leadership in Melanesia and Australia; increase their knowledge of how to manage and promote internal party democracy, policy development and lay party/parliamentary party relations better appreciate their role in leading the development and operation of their parties; develop strategies for successful party leadership; and establish peer support networks for continuous improvement. As with all our programs, PPLP’s objective is the transfer of skills and knowledge, not only from Australia to our partners, but crucially amongst our partner countries themselves, in this case Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Fiji. 1 Day 1 – Monday 27th May 8.15am Registration 8.45am Administration Briefing Josh Wrest, CDI 9:00am Course Opening and Welcome Dr Stephen Sherlock, CDI Director Grant Harrison, CDI Deputy Director 9.20am Welcome - Course Overview Dr Norm Kelly CDI Associate 9.40am Introductions Participants 10.30am - Morning Tea (and group photo) 11.00am The Contribution that -

Budget Estimates 2005-06 (Supplementary)

E565_06 attachment MP name Electorate Letter dated ACT Ms Annette Ellis MP Canberra 22-Aug-05 Mr Bob McMullan MP Fraser 22-Aug-05 NT Mr David Tollner MP Solomon 12-Sep-05 QLD Mr Bernie Ripoll MP Oxley 19-Sep-05 The Hon Robert Katter MP Kennedy 19-Sep-05 Mr Wayne Swan MP Lilley 19-Sep-05 Dr Craig Emerson MP Rankin 19-Sep-05 Mr Kevin Rudd MP Griffith 19-Sep-05 The Hon Arch Bevis MP Brisbane 19-Sep-05 Ms Kirsten Livermore MP Capricornia 19-Sep-05 The Hon David Jull MP Fadden 19-Sep-05 Mr Andrew Laming MP Bowman 19-Sep-05 The Hon De-Anne Kelly MP Dawson 19-Sep-05 Mr Ross Vasta MP Bonner 19-Sep-05 The Hon Mal Brough MP Longman 19-Sep-05 The Hon Warren Truss MP Wide Bay 19-Sep-05 Mr Cameron Thompson MP Blair 19-Sep-05 Mr Steven Ciobo MP Moncrieff 19-Sep-05 The Hon Teresa Gambaro MP Petrie 19-Sep-05 The Hon Peter Dutton MP Dickson 19-Sep-05 Mr Michael Johnson MP Ryan 19-Sep-05 The Hon Gary Hardgrave MP Moreton 19-Sep-05 The Hon Warren Entsch MP Leichhardt 19-Sep-05 Mrs Margaret May MP McPherson 19-Sep-05 Mr Peter Lindsay MP Herbert 19-Sep-05 The Hon Bruce Scott MP Maranoa 19-Sep-05 The Hon Peter Slipper MP Fisher 19-Sep-05 The Hon Alex Somlyay MP Fairfax 19-Sep-05 Mr Paul Neville MP Hinkler 19-Sep-05 The Hon Ian Macfarlane MP Groom 19-Sep-05 Mrs Kay Elson MP Forde 19-Sep-05 SA Dr Andrew Southcott MP Boothby 19-Sep-05 Ms Kate Ellis MP Adelaide 19-Sep-05 Mr Steve Georganas MP Hindmarsh 19-Sep-05 Mr Rodney Sawford MP Port Adelaide 19-Sep-05 Mr Patrick Secker MP Barker 19-Sep-05 Mr Barry Wakelin MP Grey 19-Sep-05 Mr Kym Richardson MP Kingston 19-Sep-05 -

Submission to the Senate Select Committee Into the Political Influence of Donations

Submission to the Senate Select Committee into the Political Influence of Donations Dr Charles Livingstone & Ms Maggie Johnson Gambling and Social Determinants Unit School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine Monash University 9 October 2017 1 Introduction Gambling in Australia is a prime cause of avoidable harm, with the harms of gambling estimated to be of the same order of magnitude as alcohol, and far higher than that associated with illicit drug consumption. (Browne et al, 2016; 2017). The gambling industry is a major donor to Australian political parties and politicians and appears to hold considerable cachet with many political actors, at both federal and state level. In this, it appears to be similar to other industries that produce harmful products, such as alcohol and tobacco. Its purpose in donating to political parties and politicians is similar; it seeks to deny the harmful effects of its products, delay or wind back reform, avoid effective regulation, and continue to extract profits for as long as possible. a) The level of influence that political donations exert over the public policy decisions of political parties, Members of Parliament and Government administration; The Australian gambling industry has utilised political donations as a mechanism to exert considerable influence over relevant public policy. This has been facilitated by the current donations regime, which has numerous flaws from the perspective of transparency and support for policy that acts in the genuine interest of the public. The industry is both significantly resourced and politically organised, and has actively sought opportunities for political engagement via donations to politicians and political parties. -

Flyer Update Western Sydney

noise and pollution directly threatens you. a western speak up, tell the government no. sydney airport no western sydney airport. threatens HAWKESBURY your quality of life and community in western sydney RICHMOND WINDSOR CASTLEREAGH SPRINGWOOD ROUSE HILL HORNSBY WOODFORD MT RIVERVIEW CASTLE HILL WAHROONGA ST MARYS BLAXLAND BAULKHAM HILLS PENRITH BLACKTOWN ST CLAIR PROSPECT RESERVOIR ERSKINE PARK GREYSTANES GLENMORE PARK PARRAMATTA HORSLEY PARK WALLACIA LUDDENHAM WARRAGAMBA KEMPS CREEK FAIRFIELD SILVERDALE CECIL PARK WARRAGAMBA DAM LIVERPOOL SYDNEY AIRPORT BRINGELLY GREENDALE HOXTON PARK THE OAKS CAMPBELLTOWN how high will a plane be over you? WALLACIA LUDDENHAM 1500 FT SILVERDALE air pollution GLENMORE PARK 2000 FT water pollution BLACKTOWN 2500 FT noise pollution ST MARYS 3700 FT PENRITH 4200 FT 24 hours a day CASTLE HILL 5000 FT MT RIVERVIEW 7 days a week Flight Paths Initial Flight Paths Longer what can you do about it? Development Term Development Aircraft Noise Greater Blue Mountains 60 - >95 dBA World Heritage Area Authorised by: No Badgerys Creek Airport, Residents Against Western Sydney Airport, Blue Mountains Conservation Society, February 2016. our communities a high speed rail what can i do? Cafes, street markets, festivals, bushwalks, lookouts, is a better option Aboriginal and European culture, art, theatre. Western A high speed rail from Sydney to Melbourne can WRITE LETTERS Sydney and the Blue Mountains has it all. We all love our reduce travel times, noise impacts, promote homes and no one wants it ruined by 24 hour aircraft noise. Write letters to your local newspapers and federal politicians telling development in regional areas along the route, them that you do not want this airport and why. -

List of Senators

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 19.1 – 20 September 2021 No. Name Electorate & Party Electorate office details & email address Parliament House State/Territory telephone & fax 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW 334A Marrickville Road, Fax: (02) 6277 8562 Marrickville NSW 2204 (PO Box 5100, Marrickville NSW 2204) Tel: (02) 9564 3588, Fax: (02) 9564 1734 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Tel: (02) 9869 4288, Fax: (02) 9869 4833 3. Allen, Dr Katrina Jane (Katie) Higgins, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 Tel: (03) 9822 4422 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, Fax: (02) 6277 8526 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel: (08) 9409 4517 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 7860 Minister for Home Affairs QLD Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227 (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel: (07) 5580 9111, Fax: (07) 5580 9700 6. Andrews, The Hon Kevin James Menzies, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4023 VIC 1st Floor 651-653 Doncaster Road, Fax: (02) 6277 4074 Doncaster VIC 3108 (PO Box 124, Doncaster VIC 3108) Tel: (03) 9848 9900, Fax: (03) 9848 2741 7. -

Criminality, Corruption and Impunity: Should Australia Join the Global Magnitsky Movement?

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Criminality, corruption and impunity: Should Australia join the Global Magnitsky movement? An inquiry into targeted sanctions to address human rights abuses House of Representatives Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade December 2020 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 ISBN 978-1-76092-168-2 (Printed version) ISBN 978-1-76092-169-9 (HTML version) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................. ix Membership of the JSCFADT Committee ......................................................................................... xiii Membership of the Sub-committee ..................................................................................................... xv Terms of reference ........................................................................................................................... xvii List of abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... xix List of recommendations ................................................................................................................... xxi 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ -

List of Members 46Th Parliament Volume 6.4 – 03 June 2020

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 6.4 – 03 June 2020 No. Name Electorate, Party Electorate office details, E-mail address Parliament House State/Territory telephone, fax 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW 334A Marrickville Road, Fax: (02) 6277 8562 Marrickville NSW 2204 (PO Box 5100, Marrickville NSW 2204) Tel: (02) 9564 3588, Fax: (02) 9564 1734 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Tel: (02) 9869 4288, Fax: (02) 9869 4833 3. Allen, Dr Katrina Jane (Katie) Higgins, LP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 Tel: (03) 9822 4422, Fax: N/A 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, Fax: (02) 6277 8526 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel: (08) 9409 4517, Fax: (08) 9409 9361 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 7070 Minister for Industry, Science and QLD Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Technology Varsity Lakes QLD 4227 (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel: (07) 5580 9111, Fax: (07) 5580 9700 6. -

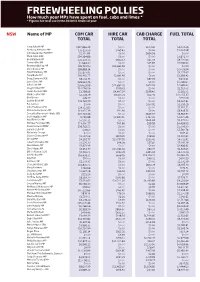

Freewheeling Pollies How Much Your Mps Have Spent on Fuel, Cabs and Limos * * Figures for Total Use in the 2010/11 Financial Year

FREEWHEELING POLLIES How much your MPs have spent on fuel, cabs and limos * * Figures for total use in the 2010/11 financial year NSW Name of MP COM CAR HIRE CAR CAB CHARGE FUEL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL Tony Abbott MP $217,866.39 $0.00 $103.42 $4,559.36 Anthony Albanese MP $35,123.59 $265.43 $0.00 $1,394.98 John Alexander OAM MP $2,110.84 $0.00 $694.56 $0.00 Mark Arbib SEN $34,164.86 $0.00 $0.00 $2,806.77 Bob Baldwin MP $23,132.73 $942.53 $65.59 $9,731.63 Sharon Bird MP $1,964.30 $0.00 $25.83 $3,596.90 Bronwyn Bishop MP $26,723.90 $33,665.56 $0.00 $0.00 Chris Bowen MP $38,883.14 $0.00 $0.00 $2,059.94 David Bradbury MP $15,877.95 $0.00 $0.00 $4,275.67 Tony Burke MP $40,360.77 $2,691.97 $0.00 $2,358.42 Doug Cameron SEN $8,014.75 $0.00 $87.29 $404.41 Jason Clare MP $28,324.76 $0.00 $0.00 $1,298.60 John Cobb MP $26,629.98 $11,887.29 $674.93 $4,682.20 Greg Combet MP $14,596.56 $749.41 $0.00 $1,519.02 Helen Coonan SEN $1,798.96 $4,407.54 $199.40 $1,182.71 Mark Coulton MP $2,358.79 $8,175.71 $62.06 $12,255.37 Bob Debus $49.77 $0.00 $0.00 $550.09 Justine Elliot MP $21,762.79 $0.00 $0.00 $4,207.81 Pat Farmer $0.00 $0.00 $177.91 $1,258.29 John Faulkner SEN $14,717.83 $0.00 $0.00 $2,350.51 Mr Laurie Ferguson MP $14,055.39 $90.91 $0.00 $3,419.75 Concetta Fierravanti-Wells SEN $20,722.46 $0.00 $649.97 $3,912.97 Joel Fitzgibbon MP 9,792.88 $7,847.45 $367.41 $2,675.46 Paul Fletcher MP $7,590.31 $0.00 $464.68 $2,475.50 Michael Forshaw SEN $13,490.77 $95.86 $98.99 $4,428.99 Peter Garrett AM MP $39,762.55 $0.00 $0.00 $1,009.30 Joanna Gash MP $78.60 $0.00 -

16 September 2020

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION WEDNESDAY, 16 SEPTEMBER 2020 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Minister for the Coordination of Education and Training: COVID-19 .............. The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Minister for Regional Development, Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Resources ........................................ The Hon. J Symes, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development, Minister for Industrial Relations and Minister for the Coordination of Treasury and Finance: COVID-19 .......................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Transport Infrastructure, Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop and Minister for the Coordination of Transport: COVID-19 ... The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Health, Minister for Ambulance Services and Minister for the Coordination of Health and Human Services: COVID-19 ....... The Hon. J Mikakos, MLC Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Roads and Road Safety . The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................ The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister -

Sidney William Jackson COLLECTOR and TREE-CLIMBER

THE NATIONAL JUNELIBRARY 2015 OF AUSTRALIA MAGAZINE SUBLIME SHELLS GALLIPOLI PANORAMA RECOVERING PARK RIDGE MAGNA CARTA’S ANNIVERSARY DARING KATE KELLY AND MUCH MORE … REVEALING THE FROM THE ROTHSCHILD KERRY STOKES PRAYER BOOK c.1505–1510 COLLECTION NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA 22 May–9 August 2015 Treasures Gallery Free Open Daily 10 am–5 pm nla.gov.au St Stephen. Suffrage, fols 218v–219r in the Rothschild Prayer Book c. 1505–1510, Kerry Stokes Collection, Perth VOLUME 7 NUMBER 2 JUNE 2015 The National Library of Australia magazine The aim of the quarterly The National Library of Australia Magazine is to inform the Australian community about the National Library of Australia’s collections and services, and its role as the information resource for the nation. Copies are distributed through the Australian library network to state, public and community libraries and most libraries within tertiary-education institutions. Copies are also made available to the Library’s international associates, and state and federal government departments and parliamentarians. Additional CONTENTS copies of the magazine may be obtained by libraries, public institutions and educational authorities. Individuals may receive copies by mail by becoming a member of the Friends of the National Library of Australia. National Library of Australia Parkes Place Finding Park Ridge: Canberra ACT 2600 02 6262 1111 Walter Burley Griffin’s nla.gov.au Final American Town Plan NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA COUNCIL Christopher Vernon’s long-held interest in an Chair: Mr Ryan Stokes Deputy Chair: Ms Deborah Thomas elusive town plan culminates in a remarkable find Members: Mr Thomas Bradley QC, The Hon. -

Remarks by Chris Hayes MP

Chris Hayes MP Federal Member for Fowler Chief Opposition Whip Regional Parliamentary Seminar Standing Against the Death Penalty in Asia Malaysia 31 October 2018 It is a pleasure to be with you all today, as we come together, in our various capacities, whether it be parliamentarians, human rights institutions or representatives of civil society, to recommit to the ultimate pursuit of a world free of the death penalty. I am grateful for the opportunity to be participating in this conference, given the significant dialogue that has come from various stakeholders in Malaysia with regards to the abolition of the death penalty. 1 I am very proud of the extensive work that has been put into making this a reality, with the Malaysian Government recently announcing that they will be completely abolishing the death penalty, as a sentence for all crimes.1 This is a true testament to the political leadership of Malaysia, the will of its people and the many voices that they have been vocal on this very pertinent issue. These plans are very welcome and have been long awaited by the international community. It is my hope that this move will encourage other countries in the region to follow suit, reigniting debate about the relevance and the role of capital punishment in today’s society. As a member of the Parliament of Australia and as a co-chair of the Australian Parliamentarians Against the Death Penalty, I am wholeheartedly committed to strengthening international public advocacy for the right to life, with there being no place for the death penalty in our modern world. -

Procedural Digest 15 16 17 18 19 No

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES March 2021 M T W T F Procedural Digest 15 16 17 18 19 No. 19 22 23 24 25 26 46th Parliament 15–25 March 2021 Selected entries contain links to video footage via Parlview. Please note that the first time you click a [Watch] link, you may need to refresh the page (ctrl+F5) for the correct starting point. Business 19.01 Statements regarding March 4 Justice Prior to question time on 15 March, the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition both made statements, by indulgence of the Chair, regarding March 4 Justice rallies held at Parliament House and elsewhere, calling for action on violence again women. [Watch] Hansard: 15 March 2021, P61-4 19.02 Motion to suspend standing orders to allow motion regarding violence against women negatived Following question time on 15 March, the Leader of the Opposition moved to suspend standing orders to allow him to move a motion calling on the Prime Minister to take certain actions in regard to violence against women. The mover and seconder were closured on division and the debate was closured on division. The suspension motion was then negatived on division. Hansard: 15 March 2021, P71-7 Votes and Proceedings: 2021/P1704-9 SOs 47, 80, 81 19.03 Customs tariff proposal On 17 March, the Assistant Minister for Customs, Community Safety and Multicultural Affairs moved Customs Tariff Proposal (No. 2) 2021. He explained that the proposal created a new tariff concession for goods used for the F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter program, in accordance with an international agreement.