Brake Constanceelaine.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

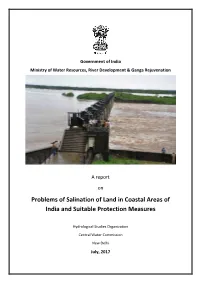

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

Goa University Glimpses of the 22Nd Annual Convocation 24-11-2009

XXVTH ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 asaicT ioo%-io%o GOA UNIVERSITY GLIMPSES OF THE 22ND ANNUAL CONVOCATION 24-11-2009 Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon ble President of India, arrives at Hon'ble President of India, with Dr. S. S. Sidhu, Governor of Goa the Convocation venue. & Chancellor, Goa University, Shri D. V. Kamat, Chief Minister of Goa, and members of the Executive Council of Goa University. Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon'ble President of India, A section of the audience. addresses the Convocation. GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 XXV ANNUAL REPORT June 2009- May 2010 GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 206 GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 GOA UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR H. E. Dr. S. S. Sidhu VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. Dileep N. Deobagkar REGISTRAR Dr. M. M. Sangodkar GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 CONTENTS Pg, No. Pg. No. PREFACE 4 PART 3; ACHIEVEMENTS OF UNIVERSITY FACULTY INTRODUCTION 5 A: Seminars Organised 58 PART 1: UNIVERSITY AUTHORITIES AND BODIES B: Papers Presented 61 1.1 Members of Executive Council 6 C; ' Research Publications 72 D: Articles in Books 78 1.2 Members of University Court 6 E: Book Reviews 80 1.3 Members of Academic Council 8 F: Books/Monographs Published 80 1.4 Members of Planning Board 9 G. Sponsored Consultancy 81 1.5 Members of Finance Committee 9 Ph.D. Awardees 82 1.6 Deans of Faculties 10 List of the Rankers (PG) 84 1.7 Officers of the University 10 PART 4: GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 1.8 Other Bodies/Associations and their 11 Composition General Information 85 Computerisation of University Functions 85 Part 2: UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS/ Conduct of Examinations 85 CENTRES / PROGRAMMES Library 85 2.1 Faculty of Languages & Literature 13 Sports 87 2.2 Faculty of Social Sciences 24 Directorate of Students’ Welfare & 88 2.3 Faculty of Natural Sciences 31 Cultural Affairs 2.4 Faculty of Life Sciences & Environment 39 U.G.C. -

A Dialogue on Managing Karnataka's Fisheries

1 A DIALOGUE ON MANAGING KARNATAKA’S FISHERIES Organized by College of Fisheries, Mangalore Karnataka Veterinary, Animal and Fisheries Sciences University (www. cofmangalore.org) & Dakshin Foundation, Bangalore (www.dakshin.org) Sponsored by National Fisheries Development Board, Hyderabad Workshop Programme Schedule Day 1 (8th December 2011) Registration Inaugural Ceremony Session 1: Introduction to the workshop and its objectives-Ramachandra Bhatta and Aarthi Sridhar(Dakshin) Management of fisheries – experiences with ‘solutions’- Aarthi Sridhar Group discussions: Identifying the burning issues in Karnataka’s fisheries. Presentation by each group Session 2: Community based monitoring – experiences from across the world- Sajan John (Dakshin) Discussion Day 2 (9th December 2011) Session 3: Overview of the marine ecosystems and state of Fisheries Marine ecosystems - dynamics and linkages- Naveen Namboothri (Dakshin) State of Karnataka Fisheries- Dinesh Babu (CMFRI, Mangalore) Discussion Session 4: Co-management in fisheries Co-management experiences from Kerala and Tamil Nadu- Marianne Manuel (Dakshin) Discussion: What role can communities play in the management of Karnataka’s fisheries? Day 3 (10th December 2011) Field session Field visit to Meenakaliya fishing village to experiment with the idea of 2-way learning processes in fisheries Group Discussion Feedback from the participants and concluding remarks 1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Format of the workshop 4 Concerns with fisheries 5 Transitions in fishing technologies and methods -

Blue Economy in India

Occupation of the Coast BLUE ECONOMY IN INDIA 2 3 contents 006 Introduction: INTRODUCTION The Blue Economy in India 010 Context Setting: Blue Growth: 006 Saviour or Ocean Grabbing? 015Losing Ground: Coastal Regulations CH 1: REGULATE 014 030 The Research Collective, the research unit of the Programme for Social Action (PSA), facilitates research around the theoretical framework and practical aspects of CH 2: RESTRUCTURE 042Sagarmala: Myth or Reality? development, industry, sustainable alternatives, equitable 074The Vizhinjam Port: Dream or Disaster growth, natural resources, community and people’s rights. Cutting across subjects of economics, law, politics, 041 081National Inland Waterways: Eco-Friendly Transport or A New environment and social sciences, the work bases itself Onslaught on Rivers? on people’s experiences and community perspectives. Our work aims to reflect ground realities, challenge 090Competing Claims: Impacts of Industrialisation on The Fishworkers detrimental growth paradigms and generate informed of Gujarat discussions on social, economic, political, environmental and cultural problems. Cover and book design by Shrujana N Shridhar 098 Retreat is Never an Option: CH 3: REALITY In Conversation With Magline Philomena Printer: Jerry Enterprises, 9873294668 102 Marine Protected Areas in India- 097 Protection For Whom? For Private Circulation Only This Report may be reproduced with 105 The Chennai Statement on Marine Protected Areas acknowledgement for public purposes. 108 What is Blue Carbon? Suggested Contribution: Rs.200/- -

Enhancing Climate Resilience of India's Coastal Communities

Annex II – Feasibility Study GREEN CLIMATE FUND FUNDING PROPOSAL I Enhancing climate resilience of India’s coastal communities Feasibility Study February 2017 ENHANCING CLIMATE RESILIENCE OF INDIA’S COASTAL COMMUNITIES Table of contents Acronym and abbreviations list ................................................................................................................................ 1 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive summary ................................................................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 13 2. Climate risk profile of India ....................................................................................................................... 14 2.1. Country background ............................................................................................................................. 14 2.2. Incomes and poverty ............................................................................................................................ 15 2.3. Climate of India .................................................................................................................................... 16 2.4. Water resources, forests, agriculture -

2009-2010, Eight Regular Meetings, Two Special Meetings of the Executive Council Were Held

GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009 -10 )0(V ANNUAL REPORT June 2009— May 2010 GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 206 1 GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 GOA UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR H. E. Dr. S. S. Sidhu VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. Dileep N. Deobagkar REGISTRAR Dr. M. M. Sangodkar GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009 -10 CONTENTS Pg. No. Pg. No. PREFACE 4 PART 3: ACHIEVEMENTS OF UNIVERSITY INTRODUCTION 5 FACULTY PART 1: UNIVERSITY AUTHORITIES AND A: Seminars Organised 58 BODIES B: Papers Presented 61 1,1 Members of Executive Council 6 C: ' Research Publications 72 1.2 Members of University Court 6 D: Articles in Books 78 1.3 Members of Academic Council 8 E: Book Reviews 80 1.4 Members of Planning Board 9 F: Books/Monographs Published 80 G. Sponsored Consultancy 81 1.5 Members of Finance Committee 9 Ph.D. Awardees 82 1.6 Deans of Faculties 10 List of the Rankers (PG) 84 1.7 Officers of the University 10 PART 4: GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 1.8 Other Bodies/Associations and their 11 Composition General Information 85 Computerisation of University Functions 85 Part 2: UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS/ CENTRES / PROGRAMMES Conduct of Examinations 85 2.1 Faculty of Languages & Literature 13 Library 85 2.2 Faculty of Social Sciences 24 Sports 87 2.3 Faculty of Natural Sciences 31 Directorate of Students' Welfare & 88 Cultural Affairs 2.4 Faculty of Life Sciences & Environment 39 U.G.C. Academic Staff College 88 2.5 Faculty of Management Studies 51 Health Centre 89 2.6 Faculty of Commerce 52 College Development Council 89 2.7 Innovative Programmes 55 (i) Research -

PAPER-I Time Allowed: 2 Hours Maximum Marks: 200

INSIGHTS ON INDIA MOCK PRELIMINARY EXAM - 2015 INSIGHTS ON INDIA MOCK TEST - 26 GENERAL STUDIES PAPER-I Time Allowed: 2 Hours Maximum Marks: 200 INSTRUCTIONS 1. IMMEDITELY AFTER THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE EXAMINATION, YOU SHOULD CHECK THAT THIS TEST BOOKLET DOES NOT HAVE ANY UNPRINTED OR TORN OR MISSING PAGES OR ITEMS, ETC. IF SO, GET IT REPLACED BY A COMPLETE TEST BOOKLET. 2. You have to enter your Roll Number on the Test Booklet in the Box provided alongside. DO NOT Write anything else on the Test Booklet. 4. This Test Booklet contains 100 items (questions). Each item is printed only in English. Each item comprises four responses (answers). You will select the response which you want to mark on the Answer Sheet. In case you feel that there is more than one correct response, mark the response which you consider the best. In any case, choose ONLY ONE response for each item. 5. You have to mark all your responses ONLY on the separate Answer Sheet provided. See directions in the Answer Sheet. 6. All items carry equal marks. 7. Before you proceed to mark in the Answer Sheet the response to various items in the Test Booklet, you have to fill in some particulars in the Answer Sheet as per instructions sent to you with your Admission Certificate. 8. After you have completed filling in all your responses on the Answer Sheet and the examination has concluded, you should hand over to the Invigilator only the Answer Sheet. You are permitted to take away with you the Test Booklet. -

Fisherwomen of the East Coastal India: a Study

International Journal of Gender and Women’s Studies June 2014, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 297-308 ISSN: 2333-6021 (Print), 2333-603X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development Fisherwomen of the East Coastal India: A Study Manju Pathania Biswas 1 and Dr. M Rama Mohan Rao 2 Abstract This article is a hypothetical study of fisherwomen fromthe Coastal areas of West Bengal, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Naduto highlight social, economic, political,education and health related issues. Fishing is a major industry in coastal states of India but still the coastal fishworkers have been one of the most vulnerable groups among the poor in India. Fisheries are an important sector of food production, providing dieteticsupplement to the food along with contributing to the agricultural exports and engaging about fourteen million people in different activities. With diverse resources ranging from deep seas to fresh waters, the country has shown constant increments in fish production since independence. Women, who constitute approximately half of India’s population (49%)play vital role in these fisheries. The contributions of the fisherwomen penetrate every aspect of post- harvest handling, preservation, processing and marketing of seafood products and provide an integral link between producers and consumers.Increase in competition, decaying resources and complex working conditions make work challenging for the fisherwomen.Among fisherwomen mobility is limited; hence they need some eco- friendly technologies, which could provide additional income to the family. Women entrepreneurs need to be encouraged in the fishing industry. Keywords: Fisherwomen, Issues, Entrepreneurs, Self Help Groups, Empowerment Introduction India stands second in the world in total fish production, after China, with a production of 7.3 million tons in 2007 (Source: FishStat, FAO, 2009). -

The Author Has Granted a Non- National Library of Canada To

National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Weiiington Street 395, rue Wdlington Onawa ON KiA ON4 OtiawaON K1AûN4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence ailowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothkque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic fonnats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE ROLES OF WOMEN FISHERFOLK IN THE FlSHlNG INDUSTRY IN INDIA AND THE IMPACTS OF DEVELOPMENT ON THElR LIVES by Constance Elaine Brake A major report submitted to the Schoot of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Studies Fisheries and Marine lnstitute Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2001 St. John's Newfoundland ABSTRACT Women in fishing communities have always been involved either directly or indirectly in the fishing industry, yet their involvement has sometimes been overlooked. In recent decades, changes in both the global fishing industry and the economy have often negatively impacted the lives of India's traditional fisherfolk, a marginalized coastal people. -

India's New Coal Geography

Energy Research & Social Science 73 (2021) 101903 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Energy Research & Social Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/erss India’s new coal geography: Coastal transformations, imported fuel and state-business collaboration in the transition to more fossil fuel energy Patrik Oskarsson a,*, Kenneth Bo Nielsen b, Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt c, Brototi Roy d a Department of Rural and Urban Development, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Sweden b Department of Social Anthropology, University of Oslo, Norway c Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University, Australia d Institute of Environmental Sciences and Technology, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The advance of renewable energy around the world has kindled hopes that coal-based energy is on the way out. Resource geography Recent data, however, make it clear that growing coal consumption in India coupled with its continued use in Energy transition China keeps coal-based energy at 40 percent of the world’s heat and power generation. To address the consol Coal energy infrastructure idation of coal-based power in India, this article analyses an energy transition to, rather than away from, carbon- Energy security intensive energy over the past two decades. We term this transition India’s new coal geography; the new coal India geography comprises new ports and thermal power plants run by private-sector actors along the coastline and fuelled by imported coal. This geography runs parallel to, yet is distinct from, India’s ‘old’ coal geography, which was based on domestic public-sector coal mining and thermal power generation. -

First Record of Two Species of Fishes from West Bengal, India and Additional New Ichthyofaunal Records for the Indian Sundarbans

International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 2020; 8(2): 06-10 E-ISSN: 2347-5129 P-ISSN: 2394-0506 (ICV-Poland) Impact Value: 5.62 First record of two species of fishes from West Bengal, (GIF) Impact Factor: 0.549 IJFAS 2020; 8(2): 06-10 India and additional new ichthyofaunal records for the © 2020 IJFAS www.fisheriesjournal.com Indian Sundarbans Received: 04-01-2020 Accepted: 08-02-2020 Priyankar Chakraborty, Kranti Yardi, Prasun Mukherjee and Priyankar Chakraborty Bharati Vidyapeeth Institute of Subhankar Das Environment Education and Research (BVIEER), Bharati Abstract Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be) Five species of fishes viz., Ichthyscopus lebeck, Lagocephalus spadiceus, Platax teira, Caesio University, Pune, Maharashtra, caerulaurea and Thysanophrys celebica are recorded from the Indian Sundarbans, the deltaic bulge of the India Ganges River in the State of West Bengal, India. Thysanophrys celebica and Lagocephalus spadiceus forms the first record for the state of West Bengal, India. Diagnostic characteristics and notes on Yardi Kranti distribution are provided in this paper. The present paper subsidises the already existing list of Bharati Vidyapeeth Institute of ichthyofaunal resources from the Indian Sundarbans region to provide a better understanding of the role Environment Education and Research (BVIEER), Bharati of different species in the functioning of the ecosystem. Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be) University, Pune, Maharashtra, Keywords: Taxonomy, biodiversity, distribution, ichthyology, mangroves, first record India 1. Introduction Prasun Mukherjee The Sundarban mangrove forests comprise about 2114 sq.km of forest cover in the state of School of Water Resources [1] Engineering, Jadavpur West Bengal, India which is about half the total estimate for mangroves of coastal India . -

Assessment of Coastal Aquaculture for India from Sentinel-1 SAR Time Series

remote sensing Article Assessment of Coastal Aquaculture for India from Sentinel-1 SAR Time Series Kumar Arun Prasad 1,2 , Marco Ottinger 2 , Chunzhu Wei 3 and Patrick Leinenkugel 2,* 1 Department of Geography, School of Earth Sciences, Central University of Tamil Nadu, Thiruvarur 610005, Tamil Nadu, India; [email protected] 2 German Remote Sensing Data Center, Earth Observation Center, German Aerospace Center, 82234 Wessling, Germany; [email protected] 3 Department of Remote Sensing, Institute of Geography and Geology, University of Wuerzburg, 97074 Wuerzburg, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-0815-328-1522 Received: 28 December 2018; Accepted: 6 February 2019; Published: 11 February 2019 Abstract: Aquaculture is one of the fastest growing primary food production sectors in India and ranks second behind China. Due to its growing economic value and global demand, India’s aquaculture industry experienced exponential growth for more than one decade. In this study, we extract land-based aquaculture at the pond level for the entire coastal zone of India using large-volume time series Sentinel-1 synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) data at 10-m spatial resolution. Elevation and slope from Shuttle Radar Topographic Mission digital elevation model (SRTM DEM) data were used for masking inappropriate areas, whereas a coastline dataset was used to create a land/ocean mask. The pixel-wise temporal median was calculated from all available Sentinel-1 data to significantly reduce the amount of noise in the SAR data and to reduce confusions with temporary inundated rice fields. More than 3000 aquaculture pond vector samples were collected from high-resolution Google Earth imagery and used in an object-based image classification approach to exploit the characteristic shape information of aquaculture ponds.