Design and Manufacturing of an Artificial Marine Conch by Bore Optimisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shell Trumpets in Mesoamerica Music-Archaelogical Evidence and Living Tradition Arnd Adje Both

Shell Trumpets in Mesoamerica Music-Archaelogical Evidence and Living Tradition Arnd Adje Both ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ceps) exhibited in the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City (Fig. 1)2. The decora- Musikarchäologische Daten belegen, daß Schnek- tion depicts a headdress consisting of a zigzag kentrompeten in vorspanischen Kulturen eine band in yellow and red with green feathers, and a große zeremonielle Bedeutung zukam. In diesem double glyph at the body whorl consisting of two Beitrag wird eine vielschichtige Musiktradition tassel headdresses with the numerical coefficients verfolgt, die trotz der abwechslungsreichen Ge- “9” and “12” indicated by bars and dots. The sym- schichte Mesoamerikas vergleichbare Elemente bolic meaning of the double glyph is still unclear3. aufweist. In Zeremonien verschiedener mexikani- One trumpet of 36 cm in length dating from A.D. scher Ethnien werden die Instrumente bis heute 500 was excavated near an altar of Tetitla, one of verwendet. Ihr Gebrauch läßt Merkmale erken- the many residential compounds of Teotihuacan. nen, die sich möglicherweise als fortlebende Rest- Several finds show that shell trumpets were also bestände alter, bereits in den frühen Kulturen deposited in ceremonial burials, possibly as a per- Mesoamerikas entstandener Musikpraktiken er- sonal item. One specimen made of a Florida Horse weisen. conch (Pleuroploca gigantea) without decoration was recently excavated in Burial 5 within the Pyra- mid of the Moon, dating from A.D. 350 (Fig. 3). 1. MUSIC-ARCHAEOLOGI- The trumpet was unearthed next to a flaked obsidi- CAL EVIDENCE an figure and pointed towards the west, where the sun is going down into the underworld. Several Shell trumpets were already known in the end of objects of greenstone (jadeite) carved in Maya style the Early Preclassic period of Mesoamerica (2000 indicate some form of contact between the ruling to 1200 B.C.), as demonstrated by sound artefacts group of Teotihuacan and Maya royal families. -

Trumpets and Horns

TRUMPETS AND HORNS NATURAL TRUMPETS SHOFAR The shofar is an ancient Jewish liturgical instrument. It is a natural trumpet without a mouthpiece and produces only two tones, the second and third harmonics. The Talmud has laid down precise instructions for its maintenance and use, as well as materials and methods of construction. The shofar is usually made from ram's horn, although the horn of any animal of the sheep or goat family may be used. The horn is softened by heat and straightened. Subsequently, it is re-bent in one of several shapes (Plate 58). A blow-hole is bored into the pointed end of the horn. In the Northern European variety of shofar, the blow-hole usually has no distinct shape. In the Israeli and Southern European type, the mouthpiece is formed into a miniature trum- pet mouthpiece. CATALOGUE # 85 SHOFAR (73-840) MIDDLE EAST Plate 58, Fig. 97. COLLECTED: Toronto, Ontario, 1973 CATALOGUE It 86 SHOFAR (73-847) MIDDLE EAST Plate 58, Fig. 98. COLLECTED: Toronto, Ontario, 1973 CATALOGUE It 87 SHOFAR (74-68) USSR A family treasure, this shofar (Plate 58, Fig. 99) was brought to Canada ca. 1900 from Minsk, Russia by Vladislaw Schwartz. Mr. Schwartz donated it to the Minsken Synagogue, Toronto upon his assumption of the presidency in 1932. COLLECTED: Toronto, Ontario, 1973 Plate 58 Shofars 1. Catalogue 087 085 2. Catalogue 3. Catalogue 086 b1-3/44 ________ 0 Scm a t 6.5 L L__— 5.5 - -- -- -—____________________ /t---- N ---A / N re 97 75.0 / .8 0 5cm Figure 96 6L Natural trumpets 125 HORA The hora is the end-blown shell trumpet of Japan. -

Ancient Seashell Resonates After 18,000 Years

PRESS RELEASE - PARIS - 10 FEBRUARY 2021 Ancient seashell resonates after 18,000 years Almost 80 years after its discovery, a large shell from the ornate Marsoulas Cave in the Pyrenees has been studied by a multidisciplinary team from the CNRS, the Muséum de Toulouse, the Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès and the Musée du quai Branly - Jacques-Chirac1: it is believed to be the oldest wind instrument of its type. Scientists reveal how it sounds in a study published in the journal Science Advances on 10th February 2021. The Marsoulas Cave, between Haute-Garonne and Ariège, was the first decorated cave to be found in the Pyrenees. Discovered in 1897, the cave bears witness to the beginning of the Magdalenian2 culture in this region, at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum. During an inventory of the material from the archaeological excavations, most of which is kept in the Muséum de Toulouse, scientists examined a large Charonia lampas (sea snail) shell, which had been largely overlooked when discovered in 1931. The tip of the shell is broken, forming a 3.5 cm diameter opening. As this is the hardest part of the shell, the break is clearly not accidental. At the opposite end, the shell opening shows traces of retouching (cutting) and a tomography scan has revealed that one of the first coils is perforated. Finally, the shell has been decorated with a red pigment (hematite), characteristic of the Marsoulas Cave, which indicates its status as a symbolic object. To confirm the hypothesis that this conch was used to produce sounds, scientists enlisted the help of a horn player, who managed to produce three sounds close to the notes C, C-sharp and D. -

Mystery Instrument Trivia!

Mystery Instrument Trivia! ACTIVITY SUMMARY In this activity, students will use online sources to research a variety of unusual wind- blown instruments, matching the instrument name with the clues provided. Students will then select one of the instruments for a deeper dive into the instrument’s origins and usage, and will create a multimedia presentation to share with the class. STUDENTS WILL BE ABLE TO identify commonalities and differences in music instruments from various cultures. (CA VAPA Music 3.0 Cultural Context) gather information from sources to answer questions. (CA CCSS W 8) describe objects with relevant detail. (CACCSS SL 4) Meet Our Instruments: HORN Video Demonstration STEPS: 1. Review the HORN video demonstration by San Francisco Symphony Assistant Principal Horn Bruce Roberts: Meet Our Instruments: HORN Video Demonstration. Pay special attention to the section where he talks about buzzing the lips to create sound, and how tightening and loosening the buzzing lips create different sounds as the air passes through the instrument’s tubing. 2. Tell the students: There many instruments that create sound the very same way—but without the valves to press. These instruments use ONLY the lips to play different notes! Mystery Instrument Trivia! 3. Students will explore some unusual and distinctive instruments that make sound using only the buzzing lips and lip pressure—no valves. Students should use online searches to match the trivia clues with the instrument names! Mystery Instrument Trivia - CLUES: This instrument was used in many places around the world to announce that the mail had arrived. Even today, a picture of this instrument is the official logo of the national mail delivery service in many countries. -

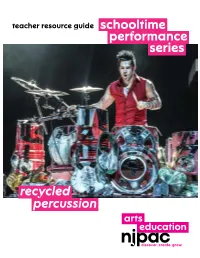

Recycled Percussion Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series recycled percussion about the performance Get ready for a musical experience that will have you clapping your hands and stomping your feet as you marvel at what can be done musically with some pretty humble materials. Recycled Percussion is a band that for more than 20 years has been making rock-n-roll music basically out of a pile of junk. Its high energy performances are a dynamic mix of rock drumming, guitar smashing and DJ-spinning, all blended into the recyclable magic of what the band calls “junk music.” Recycled Percussion’s immersive show expands the boundaries of modern percussion, combining the visual spectacle of marching band-style beats with the rhythmic musical complexity of the stationary drum set. Then they give their music a truly wacky twist by using everyday objects like power tools, ladders, buckets and trash cans, and turning them into rock instruments. Recycled Percussion is more than just performance. It’s an interactive experience where each audience member has the chance to get in on the act. If you’ve even clapped your hands to the beat of a song, or picked up a pencil and tapped out a rhythm on your desk, then you’ll know what to do. Grab the drumstick or unique instrument you’ll be handed when you come to the show and be ready to play your own special beat with Recycled Percussion. 2 recycled percussion njpac.org/education 3 about recycled in the A conversation with percussion spotlight band members from Recycled Percussion Recycled Percussion began in 1995 when drummer What exactly is “junk rock”? What are its origins? What was it like to be on America’s Got Talent? Justin Spencer formed the band to perform in his Did you or someone else come up with the name? America’s Got Talent was a really cool experience for us high school talent show in Goffstown, New Hampshire. -

The Musical Eclecticism of Ch' Angguk

National Music and National Drama: The Musical Eclecticism of Ch' angguk Andrew Killick Florida State University A lone p' ansori singer, delivering a sorrowful passage in front of a folding screen, is interrupted by loud blasts on the straight trumpet (nabal) and conch shell (nagak) from the back of the auditorium. A colorful parade files down the aisle playing the raucous royal processional music Taec/z'wit'a. On reaching the stage, the music changes to the banquet version of the same rhythmic material, Ch'wit'a, and the procession enters an elaborate set representing the yamen of the Governor of Namw6n. The new Governor, Pyan Hakto, takes the seat of honor, his white-robed officials stand in attendance, and a group of female entertainers (kisaeng) lines up to solicit his favors. Such a mixture of theatrical presentation, p' ansori singing, and other varieties of Korean music, is to be seen only in the opera form ch'anggflk. This was a scene from a ch'mzggrik production of The Story of Ch'zmlzyang in the main hall of the National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts in Seoul, performed by a visiting troupe from the National Center for Korean Folk Performing Arts in Namw6n, on May 29, 2000. The Korean names of both institutions, Kungnip Kugagwon and Kungnip Minsok Kugagw'in, include the words kungnip or "national" and kllgak or "national music"; and cJz'anggrlk itself was once known as kllkkLlk or "national drama," a usage that is still retained by all-female y6s6ng kllkkrik troupes and by a mixed provincial troupe, the Kwangju Sirip Kukk?ktan. -

Coexistence of Classical Music and Gugak in Korean Culture1

International Journal of Korean Humanities and Social Sciences Vol. 5/2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14746/kr.2019.05.05 COEXISTENCE OF CLASSICAL MUSIC AND GUGAK IN KOREAN CULTURE1 SO HYUN PARK, M.A. Conservatory Orchestra Instructor, Korean Bible University (한국성서대학교) Nowon-gu, Seoul, South Korea [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7848-2674 Abstract: Classical music and Korean traditional music ‘Gugak’ in Korean culture try various ways such as creating new music and culture through mutual interchange and fusion for coexistence. The purpose of this study is to investigate the present status of Classical music in Korea that has not been 200 years old during the flowering period and the Japanese colonial period, and the classification of Korean traditional music and musical instruments, and to examine the preservation and succession of traditional Gugak, new 1 This study is based on the presentation of the 6th international Conference on Korean Humanities and Social Sciences, which is a separate session of The 1st Asian Congress, co-organized by Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland and King Sejong Institute from July 13th to 15th in 2018. So Hyun PARK: Coexistence of Classical Music and Gugak… Korean traditional music and fusion Korean traditional music. Finally, it is exemplified that Gugak and Classical music can converge and coexist in various collaborations based on the institutional help of the nation. In conclusion, Classical music and Korean traditional music try to create synergy between them in Korean culture by making various efforts such as new attempts and conservation. Key words: Korean Traditional Music; Gugak; Classical Music; Culture Coexistence. -

Poemes Electroniques John Kenny: Carnyx, Alto, Tenor & Bass Trombones, Alphorn, Conch, Messo American Gourd Trumpets

John Kenny/Chris Wheeler Poemes Electroniques John Kenny: Carnyx, alto, tenor & bass trombones, alphorn, conch, Messo American gourd trumpets. Chris Wheeler: sound projection, turntabling. From 1980 to 2004, John Kenny performed internationally as a duo with the legendary sound designer John Whiting (of Electric Phoenix fame). In March 2004, after a final tour together throughout Ireland, with the Vanbrough String Quartet, John Whiting retired - at the age of 73. Over the previous three years, Christopher Wheeler had frequently gone out on the road as assistant to John Whiting, and acted as recording producer for John Kenny. From April 2004, Kenny invited Chris Wheeler to join him as a duo, not only to preserve the repertoire established over so many years, but more importantly to develop an entirely new repertoire. Wheeler is not only a superb sound projectionist - he is also a fine trombonist and composer, and is rapidly becoming recognised as one of the UK's most exciting and adventurous DJs. Kenny and Wheeler made their debut as a duo in July 2004 at the Arctic Trombone Festival in Tromso, Norway, giving the world premier of Ankh by Morris Pert, followed by a Deveron Arts residency in the ancient north eastern Scottish town of Huntly, where they created the electroacoustic tone poem Doric using environmental sounds of the natural and human landscapes of the region where the carnyx was originally made and used. Kenny and Wheeler have since performed at the Edinburgh Dialogues, and Belfast Sonorities festivals, the Dartington International Summer School, and St. Magnus Festival, and the Sage, Gateshead. -

Canadian Brass

SCHOOL DAY PERFORMANCES FOR PUBLIC, PRIVATE, AND HOME SCHOOLS, GRADES PreK-12 Canadian Brass IMPACT BRASS CLASS ON THE This season we invite school communities to explore the Did you know that the didgeridoo, the shofar, the vuvuzela, and the performing arts through a selection of topics that reveal the conch are all brass instruments? The didgeridoo, an instrument created IMPACT of the Arts for Youth. by Aboriginal Australians, is typically made from a hard wood like eucalyptus or even from thick bamboo. Literally a horn from a ram, the shofar is the ancient instrument of Jewish tradition. The South African MAP Introduction to the arts vuvuzela can be crafted from plastic or aluminum and a conch is the CANADIAN BRASS ORIGINATED IN Meaning and cultural context shell from a sea snail or a mollusk. But the saxophone is made of brass TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA. and it’s a woodwind instrument. And some flutes are formed from CURRENT MEMBERS LIVE IN CITIES brass too. So, what’s a brass instrument anyway? Production ALL ACROSS NORTH AMERICA. Art-making and creativity Your task: investigate what makes an instrument suitable for the ABOUT THE ARTISTS brass classification, then choose a brass instrument to research in more Careers detail. You could choose one of the four instruments played by the With their “unbeatable blend of Canadian Brass or choose a less typical member of the brass family. TORONTO, ONTARIO, virtuosity, spontaneity, and humor,” Training Part of your research can take place during the Canadian Brass concert CANADA as you listen and learn from the musicians. -

Archaeoacoustics: Re-Sounding Material Culture

Archaeoacoustics: Re-Sounding Material Culture Miriam A. Kolar Archaeoacoustics probes the dynamical potential of archaeological ma- Address: terials, producing nuanced understandings of sonic communication, and Five Colleges, Inc. re-sounding silenced places and objects. 97 Spring Street Acoustical Experiments in Archaeological Settings Amherst, Massachusetts 01002 Acoustical First Principles in Practice: Echoes and Transmission Range USA Atop a 150-meter-long, 3,000-year-old stone-and-earthen-mortar building, 20 to Email: 40 meters higher than surrounding plazas, two Andean colleagues and I listened [email protected] to cascading echoes produced via giant conch shell horns known in the Andes as pututus (see Figure 1). Riemann Ramírez, José Cruzado, and I were testing and documenting the performance of an archaeologically appropriate sound source at the UNESCO World Heritage site at Chavín de Huántar, Perú (available at acousticstoday.org/chavin), located at the center of a 400- to 500-meter-wide val- ley 3,180 meters above sea level. Our objective for this experiment, conducted in 2011, was to measure sound transmission via its return from landform features surrounding the site. Although we concurred that we perceived the echoes “swirl- ing around from all directions,” our mission that day was more than reporting subjective impressions. By recording the initial sound and returning echo se- quence using a co-located audio recorder, along with the ambient conditions of temperature and humidity important to calculating the contextual speed of sound in air, I could make precise calculations in postsurvey data analyses regarding the distances of surfaces producing discrete echoes. Via this typical archaeoacousti- cal experiment, we confirmed that the closest rockface on the steep western hill- side, known to locals as “Shallapa,” produced discrete audible echoes with little signal distortion. -

The Shofar and Its Symbolism

83 The Shofar and its Symbolism Malcolm Miller Part I: The shofar's symbolism in biblical and historical sources There is a sense of expectation in the silence before the shofar sound, followed by unease evoked by the various blasts. Part of its mystery lies in the interplay of the silence, the piercing sound, and the hum of the people praying. On its most basic level, the shofar can be seen to express what we cannot find the right words to say. The blasts are the wordless cries of the People of Israel. The shofar is the instrument that sends those cries of pain and sorrow and longing hurtling across the vast distance towards the Other. (Michael Strassfeld)1 This very poetic description of the shofar in its ritual performance highlights both the particularly Jewish and the universal elements of the instrument. The emotional associations and the use of the instrument as a symbol of memory and identity may find resonances with many religious faiths. Its specifically Jewish connotations are especially poignant at the start of the twenty-first century, yet the symbolism of the shofar extends far beyond the "cries of pain and sorrow," reaching across history to its biblical origins, to evoke a plethora of associations. As I hope to illustrate in the present article, the shofar has generated a rich nexus of metaphorical tropes, those of supernatural power, joy, freedom, victory, deliverance, national identity, moral virtue, repentance, social justice, and many other topics, some of which have remained constant while others have changed. At the heart of the matter is the appreciation of the shofar as not merely a functional instrument, as often believed, but a "musical" one, whose propensity to evoke a profound aesthetic response has led to multiple interpretations of its symbolism. -

Jeremy Montagu the Conch P.1 of 9 the Conch Its Use and Its

Jeremy Montagu The Conch p.1 of 9 The Conch Its Use and its Substitutes from Prehistory to the Present Day Jeremy Montagu Of all the prehistoric trumpets, perhaps the first, certainly the most widespread in use, with some interesting gaps in its distribution that we shall come to later, and perhaps often the most important trumpet, has been the conch, a trumpet made from the shell of a marine gastropod. This use of such shells goes back to remote antiquity, and the conch is certainly one of mankind’s earliest trumpets. It is far easier to knock the tip off the spire of a shell than to remove the point of a cow horn, or of a goat horn, or of an elephant tusk. It is easier still to knock, chip, or drill a hole in the side of the shell, but we have no evidence for side-blown shells outside of Oceania and a small part of East Africa. There is one shell trumpet known from the Upper Palaeolithic period and many from the Neolithic in various parts of Europe, some of them hundreds of kilometres from the sea.Thus these conches are far earlier than Tut-ankh-amūn’s trumpets i, which must date from somewhere before 1343 BCE, the date of the Pharaoh’s death ii, and are also some twelve hundred years earlier than the Danish lurs, which, dating from around 800 BCE, and which are otherwise the oldest surviving European hornsiii. Since many of these shells were found in graves, and at other ritual sites, it has been presumed that they were of some importance, and that they were probably used as ritual instruments.