The Didjeridu Is to Hear the Universe Calling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Skull of the Upper Cretaceous Snake Dinilysia Patagonica Smith-Woodward, 1901, and Its Phylogenetic Position Revisited

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2012, 164, 194–238. With 24 figures The skull of the Upper Cretaceous snake Dinilysia patagonica Smith-Woodward, 1901, and its phylogenetic position revisited HUSSAM ZAHER1* and CARLOS AGUSTÍN SCANFERLA2 1Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, Avenida Nazaré 481, Ipiranga, 04263-000, São Paulo, SP, Brasil 2Laboratorio de Anatomía Comparada y Evolución de los Vertebrados. Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘Bernardino Rivadavia’, Av. Angel Gallardo 470 (1405), Buenos Aires, Argentina Received 23 April 2010; revised 5 April 2011; accepted for publication 18 April 2011 The cranial anatomy of Dinilysia patagonica, a terrestrial snake from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina, is redescribed and illustrated, based on high-resolution X-ray computed tomography and better preparations made on previously known specimens, including the holotype. Previously unreported characters reinforce the intriguing mosaic nature of the skull of Dinilysia, with a suite of plesiomorphic and apomorphic characters with respect to extant snakes. Newly recognized plesiomorphies are the absence of the medial vertical flange of the nasal, lateral position of the prefrontal, lizard-like contact between vomer and palatine, floor of the recessus scalae tympani formed by the basioccipital, posterolateral corners of the basisphenoid strongly ventrolaterally projected, and absence of a medial parietal pillar separating the telencephalon and mesencephalon, amongst others. We also reinterpreted the structures forming the otic region of Dinilysia, confirming the presence of a crista circumfenes- tralis, which represents an important derived ophidian synapomorphy. Both plesiomorphic and apomorphic traits of Dinilysia are treated in detail and illustrated accordingly. Results of a phylogenetic analysis support a basal position of Dinilysia, as the sister-taxon to all extant snakes. -

Shell Trumpets in Mesoamerica Music-Archaelogical Evidence and Living Tradition Arnd Adje Both

Shell Trumpets in Mesoamerica Music-Archaelogical Evidence and Living Tradition Arnd Adje Both ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ceps) exhibited in the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City (Fig. 1)2. The decora- Musikarchäologische Daten belegen, daß Schnek- tion depicts a headdress consisting of a zigzag kentrompeten in vorspanischen Kulturen eine band in yellow and red with green feathers, and a große zeremonielle Bedeutung zukam. In diesem double glyph at the body whorl consisting of two Beitrag wird eine vielschichtige Musiktradition tassel headdresses with the numerical coefficients verfolgt, die trotz der abwechslungsreichen Ge- “9” and “12” indicated by bars and dots. The sym- schichte Mesoamerikas vergleichbare Elemente bolic meaning of the double glyph is still unclear3. aufweist. In Zeremonien verschiedener mexikani- One trumpet of 36 cm in length dating from A.D. scher Ethnien werden die Instrumente bis heute 500 was excavated near an altar of Tetitla, one of verwendet. Ihr Gebrauch läßt Merkmale erken- the many residential compounds of Teotihuacan. nen, die sich möglicherweise als fortlebende Rest- Several finds show that shell trumpets were also bestände alter, bereits in den frühen Kulturen deposited in ceremonial burials, possibly as a per- Mesoamerikas entstandener Musikpraktiken er- sonal item. One specimen made of a Florida Horse weisen. conch (Pleuroploca gigantea) without decoration was recently excavated in Burial 5 within the Pyra- mid of the Moon, dating from A.D. 350 (Fig. 3). 1. MUSIC-ARCHAEOLOGI- The trumpet was unearthed next to a flaked obsidi- CAL EVIDENCE an figure and pointed towards the west, where the sun is going down into the underworld. Several Shell trumpets were already known in the end of objects of greenstone (jadeite) carved in Maya style the Early Preclassic period of Mesoamerica (2000 indicate some form of contact between the ruling to 1200 B.C.), as demonstrated by sound artefacts group of Teotihuacan and Maya royal families. -

Human Origins

HUMAN ORIGINS Methodology and History in Anthropology Series Editors: David Parkin, Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford David Gellner, Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford Volume 1 Volume 17 Marcel Mauss: A Centenary Tribute Learning Religion: Anthropological Approaches Edited by Wendy James and N.J. Allen Edited by David Berliner and Ramon Sarró Volume 2 Volume 18 Franz Baerman Steiner: Selected Writings Ways of Knowing: New Approaches in the Anthropology of Volume I: Taboo, Truth and Religion. Knowledge and Learning Franz B. Steiner Edited by Mark Harris Edited by Jeremy Adler and Richard Fardon Volume 19 Volume 3 Difficult Folk? A Political History of Social Anthropology Franz Baerman Steiner. Selected Writings By David Mills Volume II: Orientpolitik, Value, and Civilisation. Volume 20 Franz B. Steiner Human Nature as Capacity: Transcending Discourse and Edited by Jeremy Adler and Richard Fardon Classification Volume 4 Edited by Nigel Rapport The Problem of Context Volume 21 Edited by Roy Dilley The Life of Property: House, Family and Inheritance in Volume 5 Béarn, South-West France Religion in English Everyday Life By Timothy Jenkins By Timothy Jenkins Volume 22 Volume 6 Out of the Study and Into the Field: Ethnographic Theory Hunting the Gatherers: Ethnographic Collectors, Agents and Practice in French Anthropology and Agency in Melanesia, 1870s–1930s Edited by Robert Parkin and Anna de Sales Edited by Michael O’Hanlon and Robert L. Welsh Volume 23 Volume 7 The Scope of Anthropology: Maurice Godelier’s Work in Anthropologists in a Wider World: Essays on Field Context Research Edited by Laurent Dousset and Serge Tcherkézoff Edited by Paul Dresch, Wendy James, and David Parkin Volume 24 Volume 8 Anyone: The Cosmopolitan Subject of Anthropology Categories and Classifications: Maussian Reflections on By Nigel Rapport the Social Volume 25 By N.J. -

Trumpets and Horns

TRUMPETS AND HORNS NATURAL TRUMPETS SHOFAR The shofar is an ancient Jewish liturgical instrument. It is a natural trumpet without a mouthpiece and produces only two tones, the second and third harmonics. The Talmud has laid down precise instructions for its maintenance and use, as well as materials and methods of construction. The shofar is usually made from ram's horn, although the horn of any animal of the sheep or goat family may be used. The horn is softened by heat and straightened. Subsequently, it is re-bent in one of several shapes (Plate 58). A blow-hole is bored into the pointed end of the horn. In the Northern European variety of shofar, the blow-hole usually has no distinct shape. In the Israeli and Southern European type, the mouthpiece is formed into a miniature trum- pet mouthpiece. CATALOGUE # 85 SHOFAR (73-840) MIDDLE EAST Plate 58, Fig. 97. COLLECTED: Toronto, Ontario, 1973 CATALOGUE It 86 SHOFAR (73-847) MIDDLE EAST Plate 58, Fig. 98. COLLECTED: Toronto, Ontario, 1973 CATALOGUE It 87 SHOFAR (74-68) USSR A family treasure, this shofar (Plate 58, Fig. 99) was brought to Canada ca. 1900 from Minsk, Russia by Vladislaw Schwartz. Mr. Schwartz donated it to the Minsken Synagogue, Toronto upon his assumption of the presidency in 1932. COLLECTED: Toronto, Ontario, 1973 Plate 58 Shofars 1. Catalogue 087 085 2. Catalogue 3. Catalogue 086 b1-3/44 ________ 0 Scm a t 6.5 L L__— 5.5 - -- -- -—____________________ /t---- N ---A / N re 97 75.0 / .8 0 5cm Figure 96 6L Natural trumpets 125 HORA The hora is the end-blown shell trumpet of Japan. -

Ancient Seashell Resonates After 18,000 Years

PRESS RELEASE - PARIS - 10 FEBRUARY 2021 Ancient seashell resonates after 18,000 years Almost 80 years after its discovery, a large shell from the ornate Marsoulas Cave in the Pyrenees has been studied by a multidisciplinary team from the CNRS, the Muséum de Toulouse, the Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès and the Musée du quai Branly - Jacques-Chirac1: it is believed to be the oldest wind instrument of its type. Scientists reveal how it sounds in a study published in the journal Science Advances on 10th February 2021. The Marsoulas Cave, between Haute-Garonne and Ariège, was the first decorated cave to be found in the Pyrenees. Discovered in 1897, the cave bears witness to the beginning of the Magdalenian2 culture in this region, at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum. During an inventory of the material from the archaeological excavations, most of which is kept in the Muséum de Toulouse, scientists examined a large Charonia lampas (sea snail) shell, which had been largely overlooked when discovered in 1931. The tip of the shell is broken, forming a 3.5 cm diameter opening. As this is the hardest part of the shell, the break is clearly not accidental. At the opposite end, the shell opening shows traces of retouching (cutting) and a tomography scan has revealed that one of the first coils is perforated. Finally, the shell has been decorated with a red pigment (hematite), characteristic of the Marsoulas Cave, which indicates its status as a symbolic object. To confirm the hypothesis that this conch was used to produce sounds, scientists enlisted the help of a horn player, who managed to produce three sounds close to the notes C, C-sharp and D. -

Burrowing Into the Inner World of Snake Evolution 15 March 2018

Burrowing into the inner world of snake evolution 15 March 2018 "So, we compared the inner ears of Yurlunggur and Wonambi to those of 81 snakes and lizards of known ecological habits," Dr. Palci says. "We concluded that Yurlunggur was partly adapted to burrow underground, while Wonambi was more of a generalist, likely at ease in more diverse environments." These interpretations are supported by other features of the skull and skeleton of the two snakes, as well as by palaeoclimate, which implies they had quite different environmental preferences (Wonambi preferred much cooler and drier Credit: Flinders University habitats). Dr. Palci is specialising in the origin, phylogenetic relationships, and evolutionary history and Looking inside the head of a snake is so much diversification of major taxonomic groups, with a easier when the snake is a fossil. special focus on living and fossil squamates (a group of reptiles that includes lizards, Flinders University and South Australian Museum amphisbaenians, and snakes). postdoctoral researcher Alessandro Palci and other evolutionary palaeontology experts have Squamate reptiles, with over 9,000 known species, used high-resolution computer tomography (CT) to represent an ideal study group to investigate look inside the inner ears of two important evolution. Australian fossil snakes – the 23 million-year-old Yurlunggur from northern Australia, and the much The research revolves around several projects in younger Wonambi, from southern Australia, which collaborations with researchers at the South went extinct only about 50,000 years ago. Australian Museum, Flinders University, the University of Adelaide and University of Alberta. These snakes are important because they are considered close to the base of the evolutionary Digital images (see below) of the fossil snakes tree of snakes, and can thus provide some Yurlunggur and Wonambi reveal the inner ear information on what the earliest snakes looked like mostly consists of a large central portion termed and how they lived, says Dr. -

Mystery Instrument Trivia!

Mystery Instrument Trivia! ACTIVITY SUMMARY In this activity, students will use online sources to research a variety of unusual wind- blown instruments, matching the instrument name with the clues provided. Students will then select one of the instruments for a deeper dive into the instrument’s origins and usage, and will create a multimedia presentation to share with the class. STUDENTS WILL BE ABLE TO identify commonalities and differences in music instruments from various cultures. (CA VAPA Music 3.0 Cultural Context) gather information from sources to answer questions. (CA CCSS W 8) describe objects with relevant detail. (CACCSS SL 4) Meet Our Instruments: HORN Video Demonstration STEPS: 1. Review the HORN video demonstration by San Francisco Symphony Assistant Principal Horn Bruce Roberts: Meet Our Instruments: HORN Video Demonstration. Pay special attention to the section where he talks about buzzing the lips to create sound, and how tightening and loosening the buzzing lips create different sounds as the air passes through the instrument’s tubing. 2. Tell the students: There many instruments that create sound the very same way—but without the valves to press. These instruments use ONLY the lips to play different notes! Mystery Instrument Trivia! 3. Students will explore some unusual and distinctive instruments that make sound using only the buzzing lips and lip pressure—no valves. Students should use online searches to match the trivia clues with the instrument names! Mystery Instrument Trivia - CLUES: This instrument was used in many places around the world to announce that the mail had arrived. Even today, a picture of this instrument is the official logo of the national mail delivery service in many countries. -

Serpent Noun

נָחָׁש serpent noun http://www.morfix.co.il/en/serpent ֶק ֶשת bow ; rainbow ; arc http://www.morfix.co.il/en/%D7%A7%D7%A9%D7%AA http://aratools.com/#word-dict-tab The Secret Power of Spirit Animals: Your Guide to Finding Your Spirit Animals and Unlocking the Truths of Nature By Skye Alexander Page 17 Rainbow Serpent This article is about an Australian Aboriginal mytholog- people,[7] Kunmanggur by the Murinbata,[2] Ngalyod by ical figure. For the aquatic snake found in the south- the Gunwinggu,[2] Numereji by the Kakadu,[3] Taipan by eastern United States, see Farancia erytrogramma. For the Wikmunkan,[2] Tulloun by the Mitakoodi,[3] Wagyl the Australian music festival, see Rainbow Serpent Fes- by the Noongar,[8] Wanamangura by the Talainji,[3] tival. and Witij by the Yolngu.[1] Other names include Bol- The Rainbow Serpent or Rainbow Snake is a com- ung,[4] Galeru,[2] Julunggul,[9] Kanmare,[3] Langal,[2] Myndie,[10] Muit,[2] Ungur,[2] Wollunqua,[2] Wonambi,[2] Wonungar,[2] Worombi,[2] Yero,[2] Yingarna,[11] and Yurlunggur.[2] 2 Development of concept Though the concept of the Rainbow Serpent has ex- isted for a long time in Aboriginal Australian cultures, it was introduced to the wider world through the work of anthropologists.[12] In fact, the name Rainbow Ser- pent or Rainbow Snake appears to have been coined in English by Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, an anthropolo- gist who noticed the same concept going under different Australian Aboriginal rock painting of the “Rainbow Serpent”. names among various Aboriginal Australian cultures, and called -

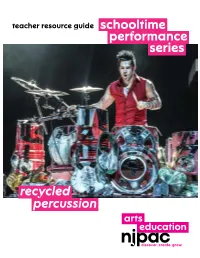

Recycled Percussion Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series recycled percussion about the performance Get ready for a musical experience that will have you clapping your hands and stomping your feet as you marvel at what can be done musically with some pretty humble materials. Recycled Percussion is a band that for more than 20 years has been making rock-n-roll music basically out of a pile of junk. Its high energy performances are a dynamic mix of rock drumming, guitar smashing and DJ-spinning, all blended into the recyclable magic of what the band calls “junk music.” Recycled Percussion’s immersive show expands the boundaries of modern percussion, combining the visual spectacle of marching band-style beats with the rhythmic musical complexity of the stationary drum set. Then they give their music a truly wacky twist by using everyday objects like power tools, ladders, buckets and trash cans, and turning them into rock instruments. Recycled Percussion is more than just performance. It’s an interactive experience where each audience member has the chance to get in on the act. If you’ve even clapped your hands to the beat of a song, or picked up a pencil and tapped out a rhythm on your desk, then you’ll know what to do. Grab the drumstick or unique instrument you’ll be handed when you come to the show and be ready to play your own special beat with Recycled Percussion. 2 recycled percussion njpac.org/education 3 about recycled in the A conversation with percussion spotlight band members from Recycled Percussion Recycled Percussion began in 1995 when drummer What exactly is “junk rock”? What are its origins? What was it like to be on America’s Got Talent? Justin Spencer formed the band to perform in his Did you or someone else come up with the name? America’s Got Talent was a really cool experience for us high school talent show in Goffstown, New Hampshire. -

The Ecological Origins of Snakes As Revealed by Skull Evolution

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-02788-3 OPEN The ecological origins of snakes as revealed by skull evolution Filipe O. Da Silva1, Anne-Claire Fabre2, Yoland Savriama1, Joni Ollonen1, Kristin Mahlow3, Anthony Herrel2, Johannes Müller3 & Nicolas Di-Poï 1 The ecological origin of snakes remains amongst the most controversial topics in evolution, with three competing hypotheses: fossorial; marine; or terrestrial. Here we use a geometric 1234567890():,; morphometric approach integrating ecological, phylogenetic, paleontological, and developmental data for building models of skull shape and size evolution and developmental rate changes in squamates. Our large-scale data reveal that whereas the most recent common ancestor of crown snakes had a small skull with a shape undeniably adapted for fossoriality, all snakes plus their sister group derive from a surface-terrestrial form with non-fossorial behavior, thus redirecting the debate toward an underexplored evolutionary scenario. Our comprehensive heterochrony analyses further indicate that snakes later evolved novel craniofacial specializations through global acceleration of skull development. These results highlight the importance of the interplay between natural selection and developmental processes in snake origin and diversification, leading first to invasion of a new habitat and then to subsequent ecological radiations. 1 Program in Developmental Biology, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, 00014 Helsinki, Finland. 2 Département Adaptations du vivant, UMR 7179 C.N.R.S/M.N.H.N., -

The Musical Eclecticism of Ch' Angguk

National Music and National Drama: The Musical Eclecticism of Ch' angguk Andrew Killick Florida State University A lone p' ansori singer, delivering a sorrowful passage in front of a folding screen, is interrupted by loud blasts on the straight trumpet (nabal) and conch shell (nagak) from the back of the auditorium. A colorful parade files down the aisle playing the raucous royal processional music Taec/z'wit'a. On reaching the stage, the music changes to the banquet version of the same rhythmic material, Ch'wit'a, and the procession enters an elaborate set representing the yamen of the Governor of Namw6n. The new Governor, Pyan Hakto, takes the seat of honor, his white-robed officials stand in attendance, and a group of female entertainers (kisaeng) lines up to solicit his favors. Such a mixture of theatrical presentation, p' ansori singing, and other varieties of Korean music, is to be seen only in the opera form ch'anggflk. This was a scene from a ch'mzggrik production of The Story of Ch'zmlzyang in the main hall of the National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts in Seoul, performed by a visiting troupe from the National Center for Korean Folk Performing Arts in Namw6n, on May 29, 2000. The Korean names of both institutions, Kungnip Kugagwon and Kungnip Minsok Kugagw'in, include the words kungnip or "national" and kllgak or "national music"; and cJz'anggrlk itself was once known as kllkkLlk or "national drama," a usage that is still retained by all-female y6s6ng kllkkrik troupes and by a mixed provincial troupe, the Kwangju Sirip Kukk?ktan. -

The Chinchilla Local Fauna: an Exceptionally Rich and Well-Preserved Pliocene Vertebrate Assemblage from Fluviatile Deposits of South-Eastern Queensland, Australia

The Chinchilla Local Fauna: An exceptionally rich and well-preserved Pliocene vertebrate assemblage from fluviatile deposits of south-eastern Queensland, Australia JULIEN LOUYS and GILBERT J. PRICE Louys, J. and Price, G.J. 2015. The Chinchilla Local Fauna: An exceptionally rich and well-preserved Pliocene verte- brate assemblage from fluviatile deposits of south-eastern Queensland, Australia. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 60 (3): 551–572. The Chinchilla Sand is a formally defined stratigraphic sequence of Pliocene fluviatile deposits that comprise interbed- ded clay, sand, and conglomerate located in the western Darling Downs, south-east Queensland, Australia. Vertebrate fossils from the deposits are referred to as the Chinchilla Local Fauna. Despite over a century and a half of collection and study, uncertainties concerning the taxa in the Chinchilla Local Fauna continue, largely from the absence of stratigraph- ically controlled excavations, lost or destroyed specimens, and poorly documented provenance data. Here we present a detailed and updated study of the vertebrate fauna from this site. The Pliocene vertebrate assemblage is represented by at least 63 taxa in 31 families. The Chinchilla Local Fauna is Australia’s largest, richest and best preserved Pliocene ver- tebrate locality, and is eminently suited for palaeoecological and palaeoenvironmental investigations of the late Pliocene. Key words: Mammalia, Marsupialia, Pliocene, Australia, Queensland, Darling Downs. Julien Louys [[email protected]], Department of Archaeology and Natural History, School of Culture, History, and Languages, ANU College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, 0200, Australia. Gilbert J. Price [[email protected]], School of Earth Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, 4072, Australia.