Analysis of Equivalent Inductance of Three-Phase Induction Motors in the Switching Frequency Range

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lci's and Synchronous Motors Applied to Roller Mills

LCI'S AND SYNCHRONOUS MOTORS APPLIED TO ROLLER MILLS For Presentation at the IEEEIPCA Cement Industry Technical Conference Salt Lake City, UT May 2000 By: James F. Zayechek G E Industrial Systems 1. Abstract A cement company concerned about high power-factor penalty costs requested an evaluation of the feasibility of using synchronous motors starting through LCl's to drive three new roller mills at a cement plant. The prior experience with roller mills centered about the application of wound rotor induction motors with either cascaded secondary resistance or liquid rheostat. By utilizing synchronous motors, there was the possibility of providing leading power factor to reduce the reactive power demands seen by the utility feeding the cement plant. It was theorized that, if sufficient power factor correction could be obtained, the payback period of the incremental additional cost of the synchronous motor drive system would be very short. After payback of the initial investment, all future energy savings gravitate directly to the bottom line as additional revenue. Several key concerns had to be addressed in evaluating the use of synchronous motors for these relatively high starting torque requirement applications. This paper discusses the electrical and mechanical evaluation leading up to the decision to proceed with this new application of synchronous motors started through an LCI. 2. Introduction Roller mills, also known as vertical mills, are becoming more prevalent in modern cement plants. These mills have application both for raw material preparation and clinker grinding to final specifications. The increasingly competitive nature of today's business environment is pushing the mill OEM's to larger mills with greater throughput. -

Power Processing, Part 1. Electric Machinery Analysis

DOCONEIT MORE BD 179 391 SE 029 295,. a 'AUTHOR Hamilton, Howard B. :TITLE Power Processing, Part 1.Electic Machinery Analyiis. ) INSTITUTION Pittsburgh Onii., Pa. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washingtcn, PUB DATE 70 GRANT NSF-GY-4138 NOTE 4913.; For related documents, see SE 029 296-298 n EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 PusiPostage. DESCRIPTORS *College Science; Ciirriculum Develoiment; ElectricityrFlectrOmechanical lechnology: Electronics; *Fagineering.Education; Higher Education;,Instructional'Materials; *Science Courses; Science Curiiculum:.*Science Education; *Science Materials; SCientific Concepts ABSTRACT A This publication was developed as aportion of a two-semester sequence commeicing ateither the sixth cr'seventh term of,the undergraduate program inelectrical engineering at the University of Pittsburgh. The materials of thetwo courses, produced by a ional Science Foundation grant, are concernedwith power convrs systems comprising power electronicdevices, electrouthchanical energy converters, and associated,logic Configurations necessary to cause the system to behave in a prescribed fashion. The emphisis in this portionof the two course sequence (Part 1)is on electric machinery analysis. lechnigues app;icable'to electric machines under dynamicconditions are anallzed. This publication consists of sevenchapters which cW-al with: (1) basic principles: (2) elementary concept of torqueand geherated voltage; (3)tile generalized machine;(4i direct current (7) macrimes; (5) cross field machines;(6),synchronous machines; and polyphase -

Dynamic Suspension Modeling of an Eddy-Current Device: an Application to Maglev

DYNAMIC SUSPENSION MODELING OF AN EDDY-CURRENT DEVICE: AN APPLICATION TO MAGLEV by Nirmal Paudel A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering Charlotte 2012 Approved by: Dr. Jonathan Z. Bird Dr. Yogendra P. Kakad Dr. Robert W. Cox Dr. Scott D. Kelly ii c 2012 Nirmal Paudel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT NIRMAL PAUDEL. Dynamic suspension modeling of an eddy-current device: an application to Maglev. (Under the direction of DR. JONATHAN Z. BIRD) When a magnetic source is simultaneously oscillated and translationally moved above a linear conductive passive guideway such as aluminum, eddy-currents are in- duced that give rise to a time-varying opposing field in the air-gap. This time-varying opposing field interacts with the source field, creating simultaneously suspension, propulsion or braking and lateral forces that are required for a Maglev system. In this thesis, a two-dimensional (2-D) analytic based steady-state eddy-current model has been derived for the case when an arbitrary magnetic source is oscillated and moved in two directions above a conductive guideway using a spatial Fourier transform technique. The problem is formulated using both the magnetic vector potential, A, and scalar potential, φ. Using this novel A-φ approach the magnetic source needs to be incorporated only into the boundary conditions of the guideway and only the magnitude of the source field along the guideway surface is required in order to compute the forces and power loss. -

A Survey of Propulsion Systems for High Capacity Personal Rapid Transit

T NO UMTA-MA-06-0 04 8-75-2 A SURVEY OF PROPULSION SYSTEMS FOR HIGH CAPACITY PERSONAL RAPID TRANSIT Thorleif Knutrud JULY 1975 FINAL REPORT DOCUMENT IS AVAILABLE TO THE PUBLIC THROUGH THE NATIONAL TECHNICAL INFORMATION SERVICE, SPRINGFIELD VIRGINIA 22161 Prepared for u.s. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION URBAN MASS TRANSPORTATION ADMINISTRATION Office of Research and Development Washington DC 20590 . NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Govern- ment assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are con- sidered essential to the object of this report. 7 , Htr . /V3 a/c? “DOT - Tsc- u. ~7&~ /£“ TECHNICAL REPORT STANDARD TITLE RAGE 3. Recipient's Catalog No. 1 . Report No. 2. Government Accesnon No. UMTA-MA- 0 6- 0 048-75-2 5. Report Date 4. T i tie and Subtitle July 1975 A SURVEY OF PROPULSION SYSTEMS FOR 6. Performing Organization Code HIGH CAPACITY PERSONAL RAPID TRANSIT 7. Author's) 8. Peefarming Orgonrzatron Report No Thorleif Knutrud DOT -TSC -UMTA-7 5-15 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No UM533/R6751 Alexander Kusko, * Inc.* 11. Controct or Grant No 161 Highland Avenue DOT -TSC- 2 03/DOT- TSC- 965 Needham Heights MA 02194 15. 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Nome ond Address Final Report U.S. Department of Transportation July 1974 - June 1975 16.Urban Mass Transportation Administration Office of Research and Development 14. -

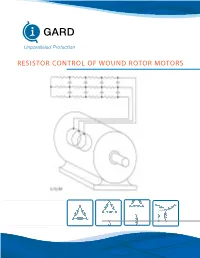

Resistor Control of Wound Rotor Motors Resistor Control of Wound Rotor Motors

RESISTOR CONTROL OF WOUND ROTOR MOTORS RESISTOR CONTROL OF WOUND ROTOR MOTORS The Wound Rotor Induction Motor or Slip Ring Motor is widely used for applications requiring speed control or low starting currents. It is very similar to the Squirrel Cage Induction Motor except that the rotor leads are brought out through slip rings (commutator rings) so that external resistance may be inserted. In fact, if we shorted these three rotor leads together, we would basically have a squirrel cage motor. The beauty of the WRM is that we can control the torque of the motor with external resistors. The purpose of this paper is to show how these resistors are sized and connected for simple speed control or starting duty. STATIR CIRCUIT The Stator, or stationary winding, of the WRM is a three-phase winding which has a cylindrical shape and occupies the outer part of the motor just inside of the motor frame. The three primary leads are usually connected (through a contactor) to the 460 VAC 3ph, 60hz power lines. The three- phase power, applied to the stator windings, produces a rotating magnetic field. The mathematics are complex and will not be covered here. The main thing to remember is that a constantly rotating magnetic field is produced whenever the stator is energized. The speed or RPM of this rotating magnetic field is a function of how many “poles” are created by the windings and the frequency of the incoming power (60 cycles per second in this country, 50 cycles per second in many European countries). With 60hz power, this synchronous RPM is a multiple of 60 such as 360, 900, 1800, etc. -

ADJUSTABLE SPEED DRIVES By: Richard D

Service Application Manual SAM Chapter 620-130 Section 6A ADJUSTABLE SPEED DRIVES By: Richard D. Beard P.E. Consultant, RSES Manufacturers’ Service Advisory Council INTRODUCTION Many commercial and industrial machines and processes require adjustable speed. Adjustable speed usually makes a machine more universally compatible and increases its versatility. Adjustable-speed drives also are being used in residential equipment, including air conditioners, refrigerators, heat pumps, furnaces, and other devices driven by motors. These drives optimize speed and torque, making them generally more efficient than non-adjustable-speed drives. An adjustable-speed motor is one in which the speed can be varied gradually over a wide range—but, once adjusted, it remains nearly unaffected by the load. A variable-speed motor is one in which the speed varies with the load, usually decreasing when the load increases. The term "adjustable speed" implies that some external adjustment, which is independent of load, will cause the speed to change. A variable-frequency inverter drive is an example. The term "variable speed" describes a drive in which load changes inherently cause significant changes in speed. A direct current series motor, for example, exhibits this characteristic. An adjustable variable-speed motor is one in which the speed can be adjusted gradually. However, once adjusted for a given load, the speed will vary with changes in the load. A multispeed motor is one that can be operated at any one of two or more definite speeds, each being practically independent of the load. The multispeed motor is neither an adjustable-speed nor a variable-speed drive. Multispeed motors usually have two, three, or four definite operating speeds. -

Design Approach to a Wound Rotor Induction Motor Towards Optimization

ISSN (Online) : 2454 -7190 ISSN (Print) 0973-8975 J.Mech.Cont.& Math. Sci., Vol.-13, No.-3, July-August (2018) Pages 159-172 Design approach to a wound rotor induction motor towards optimization 1Pritish Kumar Ghosh, 2Pradip Kumar Sadhu, 3Amarnath Sanyal, *4DebabrataRoy, 5Biswajit Dutta 1,2Electrical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology (Indian School of Mines), Dhanbad, 826004, India 3Ex Power Engineering, Jadavpur University, Kolkata,W.B.- 700032,India 4Electrical Engineering,Techno International Batanagar, South 24Parganas, W.B.- 700141,India 5ElectricalEngineering,Seacom Engineering College,Howrah,W.B.-711302,India [email protected],[email protected],3ansanyal@yahoo. co.in,[email protected],[email protected], *Corresponding author: Debabrata Roy, Abstract About 88% of the driving power is produced by 3-phase and single-phase induction motors. In most part it is by squirrel-cage motors, only a small fraction by the slip-ring or phase-wound type. It is because the cage-type motors are relatively inexpensive. But they suffer from low p.f. operation and low starting torque which cannot be manipulated by inserting resistance in the rotor circuit. Also, this type of induction motors is not easily speed-adjustable. Though a little more expensive, the slip-ring type induction motors do not have these disadvantages. Therefore, they are used as speed-adjustable drives and for drives where heavy duty starting is involved. The design of any kind of power equipment should be made cost-optimally in the present day competitive market. A new approach to reaching optimal solution has been shown in this paper by the method of sequential searching with respect to the chosen design variables. -

Dissectible Motors

Dissectible Motors Educational Training Equipment for the 21st Century Bulletin 258E HDI-100 Dissectible Motors Purpose Hampden Dissectible Motors, Series HDI-100, are a versatile aid in teaching the construction, principle of operation, and operating character- istics of fractional horsepower motors. As such they complement and extend the Hampden Series 100 Rotating Electrical Machines Program. Description The four stators and corresponding rotors of Hampden’s Dissectible Motors are the same ones used in standard industrial motors. This provides the student with realistic construction and operating characteristics. Commutator, brushes, centrifugal switch, etc., may all be observed during operation. Each motor assembles in minutes. First the student clamps the selected stator on the ter- Single-phase motor assembled on standard mounting base. Note protective clear plastic cover. minal panel/base. Next, the rotor is inserted Shipping Weight: 125 lbs. and held in position by specially designed end bells. A coupling flange is then secured to the motor shaft. The student then chooses the ter- minal panel overlay for that motor and begins the experimentation. Hampden Dissectible Motors are furnished complete with cords. The motor program includes the following four motors: 1. DC Motor. This is a four-pole machine which may be operated as a shunt, or com- pound motor. Hampden Dissectible Motors include DC and Single-phase and Three-phase AC in fractional horsepower size. 2. Single-Phase AC Squirrel-Cage Induction Motor. This is a four-pole machine, rated at 1725 rpm, which operates on 115 or 230 MODEL WRM-100-HDI volts. Dissectible Wound Rotor Motor 3. Three-Phase, Four-Pole Squirrel-Cage Induction Motor. -

Wound Rotor Motor Brochure

Wound Rotor™ MOTOR TECHNOLOGY How It Works Wound rotor motors are an extremely versatile breed of induction motors. Featuring a rugged design, these machines provide the unique ability to gradually bring up to speed high-inertia equipment and large loads smoothly and easily. Wound rotor motors also can develop high starting torque at standstill - while maintaining low inrush. Long Wound Rotor Induction motor life is ensured with the use of external resistor banks Motor Applications or liquid rheostats that dissipate heat build-up generated during motor start-up. TECO-Westinghouse Motor Company Wound Rotor What makes the wound rotor motor a unique induction Induction Motors combine outstanding performance with machine is its rotor. Instead of a series of rotor bars, a set of an advanced long-life design. Available in ratings from insulated rotor coils is used to accept external impedances. 5 HP up to 15,000 HP, these rugged workhorses are ideal The rotor windings are similar to those found on a DC for many demanding applications including: armature, with the coils connected together to a set of rings that make contact with carbon-composite brushes. The L Ball and Sag Mills circuit is completed by connecting the brushes to a set of L Cranes impedances such as a resistor bank or liquid rheostat. This L Hoists rotor construction design allows for a varying resistance L Pumps from almost short-circuit condition to an open-circuit L Fans and Blowers condition with infinite external resistance. By modifying the L Chippers resistance, the speed-torque characteristics can be altered. L Conveyors This allows for the torque to remain high, the inrush low, L Banbury Mixers and the speed varied. -

AC Motor Theory This Worksheet and All Related Files Are Licensed

AC motor theory This worksheet and all related files are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, version 1.0. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0/, or send a letter to Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA. The terms and conditions of this license allow for free copying, distribution, and/or modification of all licensed works by the general public. Resources and methods for learning about these subjects (list a few here, in preparation for your research): 1 Questions Question 1 A technique commonly used in special-effects lighting is to sequence the on/off blinking of a string of light bulbs, to produce the effect of motion without any moving objects: 123123123123 all "1" bulbs lit 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 all "2" bulbs lit Time 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 all "3" bulbs lit 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 all "1" bulbs lit phase sequence = 1-2-3 bulbs appear to be "moving" from left to right What would the effect be if this string of lights were arranged in a circle instead of a line? Also, explain what would have to change electrically to alter the ”speed” of the blinking lights’ ”motion”. file 00734 2 Question 2 If a set of six electromagnet coils were spaced around the periphery of a circle and energized by 3-phase AC power, what would a magnetic compass do that was placed in the center? Physical arrangement of coils Coil 1a Coil connection pattern Coil Coil Coil 2a 3b 1a Coil Coil 1b Compass Coil 2a 2b Coil 3a Coil Coil 3a Coil 3b 2b Coil 1b Hint: imagine the electromagnets were light bulbs instead, and the frequency of the AC power was slow enough to see each light bulb cycle in brightness, from fully dark to fully bright and back again. -

EDCA-M4-Ktunotes.In .Pdf

Electrical Drives and control for Automation-Module IV THREE PHASE INDUCTION MOTOR The 3-phase induction motor has a stator and a rotor. The stator carries a 3-phase winding (called stator winding), while the rotor carries a short-circuited winding (called rotor winding). Only the stator winding is fed from 3-phase supply. The rotor winding derives its voltage and power from the externally energized stator winding through electromagnetic induction and hence the name. The Induction machines can be considered as a transformer with a rotating secondary in the sense that the power is transferred from the stator (primary) to the rotor (secondary) winding only by mutual induction and it can, therefore, be described as a “transformer type” a.c machine in which electrical energy is converted into mechanical energy. Advantages It has simple and rugged construction. It is relatively cheap. It requires little maintenance. It has high efficiency, good speed regulation and reasonably good power factor. It has self starting torque. Disadvantages It is essentially a constant speed motor and its speed cannot be changed easily. Its starting torque is inferior to d.c motors. CONSTRUCTION A three phase induction motor has 4 main parts: 1. Frame 2. Stator 3. Rotor 4. Shaft and Bearings The stator houses a 3-phase winding which is fed with electric power. The rotor is placed inside the stator and both are separated by an air gap. 1. Frame It is the outerKTUNOTES.IN body of the motor. Its function are to support the stator core and winding, to protect the inner parts of the machine and serve as a ventilating housing or means of guiding the coolant into effective channels. -

DC Motors Parameter Estimation.Pdf

GENERATORS AND MOTORS 7.66 DIVISION 7 2. Stalling of induction motors that are operating close to full load or slightly over full load 3. Objectionable dips in the light output of lamps and flickering of lamps 4. In the case of small private generating plants, danger of overloading of gen- erators. Each electric power company has definite rules for permissible starting currents for motors supplied from its system. At present there is no standardization of these rules, each company having its own set of rules. Some of these rules limit the starting current on a basis of an allowable percentage of full-load current of the motor. With one of the newer rules, called the increment method, the maximum starting current of any motor must not be greater than a certain number of amperes per kilowatt of the customer’s maximum-demand load. 133. The speed regulation of a motor is the percentage drop in speed be- tween no load and full load based on the full-load speed. no-load speed Ϫ full-load speed Percent speed regulation ϭϫ100 (3) full-load speed DIRECT-CURRENT MOTORS 134. Direct-current motors. All dc motors must receive their excitation from some outside source of supply. Therefore they are always separately excited. The interconnection of the field and armature windings can be made, however, in one of the three different ways employed for self-excited dc generators. A dc motor may be designed, therefore, to operate with its field connected in parallel or in series with its armature, producing, respectively, a shunt or a series motor.