Hyperion Volume • V • • • • • Issue • 1 • • • • • May • 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reston, a Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts

Reston, A Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts PREPARED FOR: Virginia Department of Historic Resources AND Fairfax County PREPARED BY: Hanbury Preservation Consulting AND William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research Reston, A Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts W&MCAR Project No. 19-16 PREPARED FOR: Virginia Department of Historic Resources 2801 Kensington Avenue Richmond, Virginia 23221 (804) 367-2323 AND Fairfax County Department of Planning and Development 12055 Government Center Parkway Fairfax, VA 22035 (702) 324-1380 PREPARED BY: Hanbury Preservation Consulting P.O. Box 6049 Raleigh, NC 27628 (919) 828-1905 AND William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research P.O. Box 8795 Williamsburg, Virginia 23187-8795 (757) 221-2580 AUTHORS: Mary Ruffin Hanbury David W. Lewes FEBRUARY 8, 2021 CONTENTS Figures .......................................................................................................................................ii Tables ........................................................................................................................................ v Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... v 1: Introduction ..............................................................................................................................1 -

The New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture NEW YORK, NEW YORK PROJECT OVERVIEW the School’S Entrance Foyer

The New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture NEW YORK, NEW YORK PROJECT OVERVIEW The school’s entrance foyer A BRIEF HISTORY he New York Studio School occupies a group of four mid-nineteenth-century townhouses at 8, 10, 12, and 14 West 8th Street in New York City’s Greenwich Village, each with a carriage house behind it opening Tonto MacDougal Alley. The properties were acquired and combined from 1907 to 1929 by sculptor and art patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the eldest surviving daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt II (1872–1942), as her salon and an artist studio space for herself and numerous fellow artists. Whitney’s first purchase was the carriage house behind #8 in 1907, a three-story building with a stable below and hayloft above, where she established her personal studio. She bought the townhouse in front of it in 1913, followed by #10 in 1923 and #14 in 1925. In 1929, in order to consolidate the complex into a whole and create the Whitney Museum of American Art, she purchased #12 from sculptor Daniel Chester French. French had first introduced her to 8th Street and maintained his own studio next to hers from 1913 on. The Whitney Museum opened in 1931 and operated at the site until 1954. When Whitney bought the townhouse at #8, she retained architect Grosvenor Atterbury to redesign it and connect it to her carriage-house studio. Atterbury built an enclosed stairway from the third floor of the townhouse to the second floor of the studio in the courtyard between the two buildings, added a copper-clad enclosed balcony to the courtyard wall of the studio, and a large north- facing skylight. -

S- 0 SOUTHERN EDUCATIONAL COMMUNICATIONS ASSOCIA Tlon SECA PRESENTS ® Firing Line" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> A'" .~ (Pe>S- 0 SOUTHERN EDUCATIONAL COMMUNICATIONS ASSOCIA Tlon SECA PRESENTS ® Firing Line

The copyright laws of the United States (Title 17, U.S. Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. If a user makes a request for, or later uses a photocopy or reproduction (including handwritten copies) for purposes in excess of fair use, that user may be liable for copyright infringement. Users are advised to obtain permission from the copyright owner before any re-use of this material. Use of this material is for private, non-comercial, and educational purposes; additional reprints and further distribution is prohibited. Copies are not for resale. All other rights reserved. For further information, contact Director, Hoover Institution Library and Archives, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-6010 © Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University. II FIRinG Line "WHY AREN'T GOOD BUILDINGS BEING BUILT?" Guests: Ada Louise Huxtable James Rossant A'" .~ (Pe>s- 0 SOUTHERN EDUCATIONAL COMMUNICATIONS ASSOCIA TlON SECA PRESENTS ® FIRinG Line Host: WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY,JR. Guests: Ada Louise Huxtable James Rossant The FIRING LINE television series is a production of the Southern Educational Subject: "Why Aren't Good Buildings Being Built?" Communications Association, 928 Woodrow St., p. O. Box 5966, Columbia, S.C., 29205, and is transmitted through the facilities of the Public Broadcasting Service. Production of these Student Participants: Jeff Feingold - Pratt Institute programs is made possible through a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Leslie Blum - Pratt Institute FI RING LINE can be seen and heard each week through public television and radio stations Roger Ferri - Pratt Institute throughout the country. Check your local newspapers for channel and time in your area. -

New York Chapter I the Am Er I Can Institute of Architects

NEW YORK CHAPTER I THE AM ER ICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS OCTOBER, 1971 VOLUME 45, NUMBER 2 SECOND SURVEY OF OFflCE ACTIVITIES MEMBERS TO RECEIVE PLAN CRITIQUE The Office Practice Committee has completed its Advance copies of the New York Chapter's critique second quarterly survey of chapter office activity of the Plan for New York City have been given to levels. Appearing with this issue of OCU LUS are the Donald Elliott, Chairman of the Planning Com results of questionnaires mailed to the entire member mission, and members of his staff, as a gesture of ship. Response to this questionnaire was excellent, courtesy. Approximately twelve copies are being sent with 101 architectural firms responding, including to members of the press. A more finished copy will most of the better known firms in the city. Activity be mailed to all chapter members. levels have been measured by numbers of technical employees (including principals) in each firm. The critique was prepared by the Commission on Urban Design with principal organization done by the The first graph shows all respondents, and the other Urban Design Committee, of which Walter Rutes was charts show responses by size of offices. Although chairman. The Urban Design Committee members minor variations occur depending on size, the general and all those who participated in its development trend of work shows a total drop of 17% since deserve credit for accomplishing a difficult task. January 1, 1971, and indicates a drop of 4.9% between March 31st and June 30, 1971. The background material has been ready since June. -

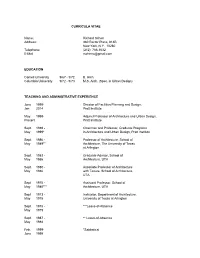

CURRICULA VITAE Name: Richard Scherr Address: 380 Rector Place

CURRICULA VITAE Name: Richard Scherr Address: 380 Rector Place, #18B New York, N.Y. 10280 Telephone: (212) 786-1632 E-Mail [email protected] EDUCATION Cornell University 9/67 - 5/72 B. Arch. Columbia University 9/72 - 5/73 M.S. Arch. (Spec. in Urban Design) TEACHING AND ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE June 1999- Director of Facilities Planning and Design, Jan 2014 Pratt Institute May 1999- Adjunct Professor of Architecture and Urban Design, Present Pratt Institute Sept. 1989 - Chairman and Professor, Graduate Programs May 1999* in Architecture and Urban Design, Pratt Institute Sept. 1986 - Professor of Architecture, School of May 1989** Architecture, The University of Texas at Arlington Sept. 1983 - Graduate Advisor, School of May 1986 Architecture, UTA Sept. 1980 - Associate Professor of Architecture May 1986 with Tenure, School of Architecture, UTA Sept 1975 - Assistant Professor, School of May 1980*** Architecture, UTA Sept 1973 - Instructor, Department of Architecture, May 1975 University of Texas at Arlington Sept. 1978 - ***Leave-of-Absence May 1979 Sept. 1987 - ** Leave-of-Absence May 1988 Feb. 1999- *Sabbatical June 1999 AWARDS May 1972 -Eidlitz Travelling Fellowship, Cornell University May 1975 -Organized Research Grant Award, UTA May 1976 -"Teacher of the Year", School of Architecture, UTA May 1976 -AMOCO Teaching Award, UTA (Honorable Mention) May 1977 -Organized Research Grant Award, UTA May 1980 -Organized Research Grant Award, UTA Apr. 1982 -Plaza Hotel Renovation, "Merit Award," Dallas A.I.A. (w/ Woodward & Assoc.) Sept. 1982 -

ARB Approved Meeting Minutes 6-13-2019

APPROVED MINUTES June 13, 2019 THE FAIRFAX COUNTY ARCHITECTURAL REVIEW BOARD Fairfax County Government Center Conference Rooms 4 & 5, 6:30 PM Members Present: Members Excused: Staff Present: John A. Burns, FAIA, Chairman Christopher Daniel, Vice Chairman Nicole Brannan, Steve Kulinski, AIA Michele Aubry, Treasurer Historic Preservation Elise Murray Planner Kaye Orr, AIA Denice, Dressel Joseph Plumpe, ASLA[Arrived at Historic Preservation 6:48] Planner Jason Sutphin Lorraine Giovinazzo, Jason Zellman, Esq. Recording Secretary Susan Notkins, AIA [Arrived at 6:39] Mr. Burns opened the June 13, 2019 meeting of the Architectural Review Board (ARB) at 6:32 p.m. at the Fairfax County Government Center. Mr. Zellman read the opening statement of purpose. APPROVAL OF THE AGENDA: Mr. Sutphin made a motion to approve the agenda as written. The motion was seconded by Mr. Kulinski, and approved on a vote of 6-0. Ms. Aubry and Mr. Daniel were absent from the meeting. Ms. Notkins and Mr. Plumpe were not present for the vote. INTRODUCTION/RECOGNITION OF GUESTS CONSENT CALENDAR ACTION ITEMS: 1. ARB-19-WDL-01 Proposal for new signage at 8859 Richmond Highway, Alexandria, VA, Tax Map 109-2 ((02)) 0013C, located in the Woodlawn Historic Overlay District. The applicant is proposing to remove the existing signage and replace with building mounted signage. Ms. Daniela Ocampo is representing the application. Mount Vernon District Presentation: • Ms. Daniela Ocampo’s daughter, Katherine, presented the proposal. She showed pictures of Oraydes Café with stores that are nearby. The Café opens early in the morning. The sign will be made out of brush gold polymetal. -

Dedication to James Rossant

Dedication to James Rossant Hyperion, Volume V, issue 1, May 2010 7 James Rossant, The Bridge, James Rossant, Floating City, watercolor pen and ink on Japanese handmade paper Hyperion James Rossant 1928 – 2009 This issue of Hyperion is dedicated to the memory of James Rossant. Rossant was an architect, city planner, artist, and professor of architecture. A long-time Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, Rossant was a partner of the architectural firm Conklin & Rossant and principal of James Rossant Architects. Among a life-time of architectural accomplishments, Rossant is best recognized for his master plan of Reston, Virginia, the Lower Manhattan Plan, and the UN-sponsored master plan for Dodoma, Tanzania. His paintings and drawings have been exhibited in galleries in various parts of the world, and have entered a variety of collections, including those of George Mason University, Columbia University, and Centre D’Architecture in Paris. In addition, he has illustrated a number of books, among them children’s books and cookbooks written by Colette Rossant, his wife. James Rossant’s name will be new to many reading this journal. However, his reputation has been significant and is widely recognized, well known by those in his own field. Despite his achievements, and one would like to think more because of them, he was not the subject of a general popularity. He did not have to suffer the indignity of a broad assent founded on the shifting and quivering tides of mass sentiment, but rather had the respect of those whose acknowledgement is rooted in the understanding that comes of and is expressed in clear and formulated ideas. -

FACULTY and STUDENT SYMPOSIUM March 23, 2011

v BALL STATE UNIVERSITY EDUCATION REDEFINED FACULTY AND STUDENT SYMPOSIUM March 23, 2011 COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE AND PLANNING Architecture . Landscape Architecture . Urban Planning v DESIGN+THINKING Welcome from the Dean Ball State University This is our fourth CAP Faculty Sympo- that fuel our design and planning pro- sium and the first time that this event in- cesses. It is of critical importance for our cludes presentations by some of our most community of learners that we understand College of talented students. Since 2008, every spring how our students gather knowledge and Architecture and semester we have invited our community translate what they have just learned into Planning of learners to submit abstracts about their peer interaction in the studio or seminar creative activities and take time out of room. their busy schedules in order to celebrate Faculty and Student the richness of our collective endeavor. Another important addition to our 2011 Symposium In our symposia we have learned much symposium is the inclusion of presenta- about each other and further confirmed our tions by faculty that have participated fundamental vocation as a community of in a special assigned leave the previous March 23, 2011 perpetual learners. year. A Special Assigned Leave is a prime opportunity for eligible faculty to con- As on previous occasions, we will have centrate during a semester or a year, in Contents the pleasure of learning more about the activities that will improve their effective- Welcome from the Dean 1 teaching, research, art, service, and learn- ness as teachers, scholars, and/or creative Schedule of Events 2 ing that happens every day in CAP. -

New York Chapter /The American Institute of Architects

NEW YORK CHAPTER /THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS SEPTEMBER, 1971 VOLUME 45, NUMBER 1 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE During our 1971-72 year I shall be wcrking and hoping for progress by the Chapter in thPse or other similar areas of concern to our profession: • The establishment of a New York Metropolitan Chapter which yvill bring together all New York City architects and give us more power politically. • Refurbish and expand our headquarters to provide better space for us and possibly for related organ izations in an effort to create an architectural center. • Keep the pressure on all city agencies which relate to architecture for better performance on their part, for a better understanding of our aims and objectives, for equitable contracts, and for paying us properly and promptly for our work-all to help make our city a better place to live and work. Max 0. Urbahn, FAIA • Continue our efforts to deal with the problem of political contributions. NEW YORKER HEADS NATIONAL AIA • Try to contribute toward a more meaningful AIA Convention in Houston next May. Since 1930, five New Yorkers have been President of • Make more effective our work for and with the AIA and now, once again, we have the honor of minority groups through our programs in Archi sending one of our own to lead the national C?rgan tectural Scholarships, the Architect's Technical ization. Max 0. Urbahn, a former NYCAIA President, Assistance Center, and in other and new ways. will officially take office later this year, but has • Explore ways for architects to make a greater already made his presence felt "on the Hill" as a vocal contribution to the formulation of national, state and representative of American architects. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Lake Anne Village Center Historic District Other names/site number: DHR# 029-5652 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing __________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: North Shore Drive; Washington Plaza West and Washington Plaza North, City or town: Reston State: VA County: Fairfax Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: X ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set -

Reston Architectural Survey Report

Reston, A Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts PREPARED FOR: Virginia Department of Historic Resources AND Fairfax County PREPARED BY: Hanbury Preservation Consulting AND William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research Reston, A Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts W&MCAR Project No. 19-16 PREPARED FOR: Virginia Department of Historic Resources 2801 Kensington Avenue Richmond, Virginia 23221 (804) 367-2323 AND Fairfax County Department of Planning and Development 12055 Government Center Parkway Fairfax, VA 22035 (702) 324-1380 PREPARED BY: Hanbury Preservation Consulting P.O. Box 6049 Raleigh, NC 27628 (919) 828-1905 AND William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research P.O. Box 8795 Williamsburg, Virginia 23187-8795 (757) 221-2580 AUTHORS: Mary Ruffn Hanbury David W. Lewes FEBRUARY 8, 2021 CONTENTS Figures .......................................................................................................................................ii Tables ........................................................................................................................................ v Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... v 1: Introduction ..............................................................................................................................1 -

New York Chapter /The American Institute of Architects

NEW YORK CHAPTER /THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS JUNE, 1971 VOLUME 44, NUMBER 10 PLAN REVIEW GOES TO NATIONAL AIA CONVENTION EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE DETROIT JUNE 20-24 The Urban Design committee, with the assistance of An AIA convention concentrates into four days an other interested committees, has studied and debated extraordinary amount of activity. One remembers the the Plan for New York City for a year. A draft review surge two years ago toward the shouldering of has been submitted to the Executive Committee, and professional responsibility to society; of the sharp it is expected that the Chapter's comments on the debate last year in Boston over the new Standards of Plan will be released to the press and distributed to Ethical Practice; of exceptionally informative civic groups and community boards in June. seminars;-and of inimitable parties for 3000 people, as when the old Grand Central Station in Chicago was Walter Rutes is Chairman of the Urban Design occupied in a blast which dismayed local columnists. Committee, and John Burgee is Chairman of the Policy Subcommittee. Other committees participating You have received material from national head in the review and their chairmen were Parks & quarters on the Detroit program, but it should be Recreation, Jay Fleischman; Housing, Seymour pointed out here that a number of issues wi II be of Jarmul; Traffic & Transportation, Stanley Lorch; particular interest to the Chapter members. Five of Historic Buildings, William Shopsin; School & College the resolutions are listed as being sponsored by us; Architecture, Ronald Haase; Natural Environment, they are titled Statute of Limitations for Professional John Grifalconi.