Introduction: Listening in on the 21St Century 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Find Artists Recent News

[LOGO] BROWSE LEARN LISTEN For Artists Search Log In / Register The Lumineers The LumineersThe Red Paintings The Red PaintingsThe So So Glos The So So Glos What Is PledgeMusic? Nam dapibus nisl vitae elit fringilla rutrum. Aenean sollicitudin, erat a elementum rutrum, neque sem pretium metus. Quis mollis nisl nunc et massa. Vestibulum sed metus in lorem tristique ullamcorper id vitae erat. Nulla mollis sapien sollicitudin lacinia lacinia. Vivamus facilisis dolor et massa placerat, at vestibulum nisl egestas. Lorem tristique Featured Artists Project Card Project Card Project Card Project Card Find Artists Placeholder Advanced Search Popular in Rock Project Card Project Card Project Card Project Card Recent News Older > 9/13 - Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit 9/10 - Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit 9/8 - Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Big Machine Showcase Project Card Project Card Project Card Project Card Browse Artists Browse Artists YOUR ACCOUNT CONNECT WITH US Learn About Pledge Learn About PledgeOrders Orders Listen to Music Listen to MusicSettings Settings Android Contact Contact Log Out Log Out Our team Our team FOR ARTISTS Careers Careers LAUNCH A PROJECT Blog Blog [LOGO] FeatureD Artists [Project CarD] [Project CarD] TrenDing this Week [Project CarD] [Project CarD] About PledgeMusic Vestibulum sed metus in lorem tristique ullamcorper id vitae erat. Nulla mollis sapien sollicitudin lacinia lacinia. Vivamus facilisis dolor et massa placerat, at vestibulum nisl egestas. [Music] [Updates] [Exclusive Items] [Personalized Recommendations] Recent News 9/13 - Lorem -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

The Twist”—Chubby Checker (1960) Added to the National Registry: 2012 Essay by Jim Dawson (Guest Post)*

“The Twist”—Chubby Checker (1960) Added to the National Registry: 2012 Essay by Jim Dawson (guest post)* Chubby Checker Chubby Checker’s “The Twist” has the distinction of being the only non-seasonal American recording that reached the top of “Billboard’s” pop charts twice, separately. (Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” topped the holiday tree in 1942, 1945, and 1947). “The Twist” shot to No. 1 in 1960, fell completely off the charts, then returned over a year later like a brand new single and did it all over again. Even more remarkable was that Checker’s version was a nearly note-for- note, commissioned mimicry of the original “The Twist,” written and recorded in 1958 by R&B artist Hank Ballard and released as the B-side of a love ballad. Most remarkable of all, however, is that Chubby Checker set the whole world Twisting, from Harlem clubs to the White House to Buckingham Palace, and beyond. The Twist’s movements were so rudimentary that almost everyone, regardless of their level of coordination, could maneuver through it, usually without injuring or embarrassing themselves. Like so many rhythm and blues songs, “The Twist” had a busy pedigree going back decades. In 1912, black songwriter Perry Bradford wrote “Messin’ Around,” in which he gave instructions to a new dance called the Mess Around: “Put your hands on your hips and bend your back; stand in one spot nice and tight; and twist around with all your might.” The following year, black tunesmiths Chris Smith and Jim Burris wrote “Ballin’ the Jack” for “The Darktown Follies of 1913” at Harlem’s Lafayette Theatre, in which they elaborated on the Mess Around by telling dancers, “Twist around and twist around with all your might.” The song started a Ballin’ the Jack craze that, like nearly every new Harlem dance, moved downtown to the white ballrooms and then shimmied and shook across the country. -

Jeanmichel Basquiat: an Analysis of Nine Paintings

JeanMichel Basquiat: An Analysis of Nine Paintings By Michael Dragovic This paper was written for History 397: History, Memory, Representation. The course was taught by Professor Akiko Takenaka in Winter 2009. Jean‐Michel Basquiat’s incendiary career and rise to fame during the 1980s was unprecedented in the world of art. Even more exceptional, he is the only black painter to have achieved such mystic celebrity status. The former graffiti sprayer whose art is inextricable from the backdrop of New York City streets penetrated the global art scene with unparalleled quickness. His work arrested the attention of big‐ shot art dealers such as Bruno Bischofberger, Mary Boone, and Anina Nosei, while captivating a vast audience ranging from vagabonds to high society. His paintings are often compared to primitive tribal drawings and to kindergarten scribbles, but these comparisons are meant to underscore the works’ raw innocence and tone of authenticity akin to the primitivism of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Cy Twombly or, perhaps, even that of the infant mind. Be that as it may, there is nothing juvenile about the communicative power of Basquiat’s work. His paintings depict the physical and the abstract to express themes as varied as drug abuse, bigotry, jazz, capitalism, and mortality. What seem to be the most pervasive throughout his paintings are themes of racial and socioeconomic inequality and the degradation of life that accompanies this. After examining several key paintings from Basquiat’s brief but illustrious career, the emphasis on specific visual and textual imagery within and among these paintings coalesces as a marked—and often scathing— social commentary. -

Schirn Presse Basquiat Boom for Real En

BOOM FOR REAL: THE SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT PRESENTS THE ART OF JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT IN GERMANY BASQUIAT BOOM FOR REAL FEBRUARY 16 – MAY 27, 2018 Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988) is acknowledged today as one of the most significant artists of the 20th century. More than 30 years after his last solo exhibition in a public collection in Germany, the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt is presenting a major survey devoted to this American artist. Featuring more than 100 works, the exhibition is the first to focus on Basquiat’s relationship to music, text, film and television, placing his work within a broader cultural context. In the 1970s and 1980s, Basquiat teamed up with Al Diaz in New York to write graffiti statements across the city under the pseudonym SAMO©. Soon he was collaging baseball cards and postcards and painting on clothing, doors, furniture and on improvised canvases. Basquiat collaborated with many artists of his time, most famously Andy Warhol and Keith Haring. He starred in the film New York Beat with Blondie’s singer Debbie Harry and performed with his experimental band Gray. Basquiat created murals and installations for New York nightclubs like Area and Palladium and in 1983 he produced the hip-hop record Beat Bop with K-Rob and Rammellzee. Having come of age in the Post-Punk underground scene in Lower Manhattan, Basquiat conquered the art world and gained widespread international recognition, becoming the youngest participant in the history of the documenta in 1982. His paintings were hung beside works by Joseph Beuys, Anselm Kiefer, Gerhard Richter and Cy Twombly. -

BEACH BOYS Vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music

The final word on the Beach Boys versus Beatles debate, neglect of American acts under the British Invasion, and more controversial critique on your favorite Sixties acts, with a Foreword by Fred Vail, legendary Beach Boys advance man and co-manager. BEACH BOYS vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music Buy The Complete Version of This Book at Booklocker.com: http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/3210.html?s=pdf BEACH BOYS vs Beatlemania: Rediscovering Sixties Music by G A De Forest Copyright © 2007 G A De Forest ISBN-13 978-1-60145-317-4 ISBN-10 1-60145-317-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Printed in the United States of America. Booklocker.com, Inc. 2007 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY FRED VAIL ............................................... XI PREFACE..............................................................................XVII AUTHOR'S NOTE ................................................................ XIX 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD 1 2. CATCHING A WAVE 14 3. TWIST’N’SURF! FOLK’N’SOUL! 98 4: “WE LOVE YOU BEATLES, OH YES WE DO!” 134 5. ENGLAND SWINGS 215 6. SURFIN' US/K 260 7: PET SOUNDS rebounds from RUBBER SOUL — gunned down by REVOLVER 313 8: SGT PEPPERS & THE LOST SMILE 338 9: OLD SURFERS NEVER DIE, THEY JUST FADE AWAY 360 10: IF WE SING IN A VACUUM CAN YOU HEAR US? 378 AFTERWORD .........................................................................405 APPENDIX: BEACH BOYS HIT ALBUMS (1962-1970) ...411 BIBLIOGRAPHY....................................................................419 ix 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD Rock is a fickle mistress. -

New York, New York

EXPOSITION NEW YORK, NEW YORK Cinquante ans d’art, architecture, cinéma, performance, photographie et vidéo Du 14 juillet au 10 septembre 2006 Grimaldi Forum - Espace Ravel INTRODUCTION L’exposition « NEW YORK, NEW YORK » cinquante ans d’art, architecture, cinéma, performance, photographie et vidéo produite par le Grimaldi Forum Monaco, bénéficie du soutien de la Compagnie Monégasque de Banque (CMB), de SKYY Vodka by Campari, de l’Hôtel Métropole à Monte-Carlo et de Bentley Monaco. Commissariat : Lisa Dennison et Germano Celant Scénographie : Pierluigi Cerri (Studio Cerri & Associati, Milano) Renseignements pratiques • Grimaldi Forum : 10 avenue Princesse Grace, Monaco – Espace Ravel. • Horaires : Tous les jours de 10h00 à 20h00 et nocturne les jeudis de 10h00 à 22h00 • Billetterie Grimaldi Forum Tél. +377 99 99 3000 - Fax +377 99 99 3001 – E-mail : [email protected] et points FNAC • Site Internet : www.grimaldiforum.mc • Prix d’entrée : Plein tarif = 10 € Tarifs réduits : Groupes (+ 10 personnes) = 8 € - Etudiants (-25 ans sur présentation de la carte) = 6 € - Enfants (jusqu’à 11 ans) = gratuit • Catalogue de l’exposition (versions française et anglaise) Format : 24 x 28 cm, 560 pages avec 510 illustrations Une coédition SKIRA et GRIMALDI FORUM Auteurs : Germano Celant et Lisa Dennison N°ISBN 88-7624-850-1 ; dépôt légal = juillet 2006 Prix Public : 49 € Communication pour l’exposition : Hervé Zorgniotti – Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 02 – [email protected] Nathalie Pinto – Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 03 – [email protected] Contact pour les visuels : Nadège Basile Bruno - Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 25 – [email protected] AUTOUR DE L’EXPOSITION… Grease Etes-vous partant pour une virée « blouson noir, gomina et look fifties» ? Si c’est le cas, ne manquez pas la plus spectaculaire comédie musicale de l’histoire du rock’n’roll : elle est annoncée au Grimaldi Forum Monaco, pour seulement une semaine et une seule, du 25 au 30 juillet. -

BANG! the BERT BERNS STORY Narrated by Stevie Van Zandt PRESS NOTES

Presents BANG! THE BERT BERNS STORY Narrated by Stevie Van Zandt PRESS NOTES A film by Brett Berns 2016 / USA / Color / Documentary / 95 minutes / English www.BANGTheBertBernsStory.com Copyright © 2016 [HCTN, LLC] All Rights Reserved SHORT SYNOPSIS Music meets the Mob in this biographical documentary, narrated by Stevie Van Zandt, about the life and career of Bert Berns, the most important songwriter and record producer from the sixties that you never heard of. His hits include Twist and Shout, Hang On Sloopy, Brown Eyed Girl, Here Comes The Night and Piece Of My Heart. He helped launch the careers of Van Morrison and Neil Diamond and produced some of the greatest soul music ever made. Filmmaker Brett Berns brings his late father's story to the screen through interviews with those who knew him best and rare performance footage. Included in the film are interviews with Ronald Isley, Ben E. King, Solomon Burke, Van Morrison, Keith Richards and Paul McCartney. LONG SYNOPSIS Music meets the Mob in this biographical documentary, narrated by Stevie Van Zandt, about the life and career of Bert Berns, the most important songwriter and record producer from the sixties that you never heard of. His hits include Twist and Shout, Hang On Sloopy, Brown Eyed Girl, Under The Boardwalk, Everybody Needs Somebody To Love, Cry Baby, Tell Him, Cry To Me, Here Comes The Night and Piece of My Heart. He launched the careers of Van Morrison and Neil Diamond, and was the only record man of his time to achieve the trifecta of songwriter, producer and label chief. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Beyond the Limit: Gender, Sexuality, and the Animal Question in (Afro)Modernity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0rw8q9k9 Author Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Beyond the Limit: Gender, Sexuality, and the Animal Question in (Afro)Modernity by Zakiyyah Iman Jackson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies and the Designated Emphasis Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Abdul JanMohamed, Chair Professor Darieck Scott Professor Brandi Catanese Professor Kristen Whissel Spring 2012 Copyright Zakiyyah Iman Jackson 2012 Beyond the Limit: Gender, Sexuality, and the Animal Question in (Afro)Modernity Abstract Beyond the Limit: Gender, Sexuality, and the Animal Question in (Afro)Modernity by Zakiyyah Iman Jackson Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Gender, Women and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Abdul JanMohamed, Chair “Beyond the Limit” provides a crucial reexamination of African diasporic literature, performance, and visual culture’s philosophical interventions into Western legal, scientific, and philosophic definitions of the human. Frederick Douglass’s speeches, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God and The Pet Negro System, Charles Burnett’s The Killer of Sheep and The Horse, Jean Michel- Basquiat’s Wolf Sausage and Monkey, Ezrom Legae’s Chicken Series, and the performance art of Grace Jones both critique and displace the racializing assumptive logic that has grounded these fields’ debates on how to distinguish human identity from that of the animal. -

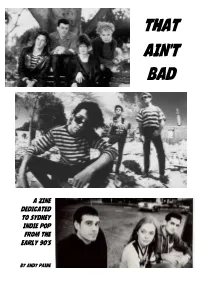

That Ain't Bad (The Main Single Off Tingles), the Band Are Drowned out by the Crowd Singing Along

THAT AIN’T BAD A ZINE DEDICATED TO SYDNEY INDIE POP FROM THE EARLY 90’S BY ANDY PAINE INTROduction In the late 1980's and early 1990's, a group of bands emerged from Sydney who all played fuzzy distorted guitars juxtaposed with poppy melodies and harmonies. They released some wonderful music, had a brief period of remarkable mainstream success, and then faded from the memory of Australia's 'alternative' music world. I was too young to catch any of this music the first time around – by the time I heard any of these bands the 90’s were well and truly over. It's hard to say how I first heard or heard about the bands in this zine. As a teenage music nerd I devoured the history of music like a mechanical harvester ploughing through a field of vegetables - rarely pausing to stop and think, somethings were discarded, some kept with you. I discovered music in a haphazard way, not helped by living in a country town where there were few others who shared my passion for obscure bands and scenes. The internet was an incredible resource, but it was different back then too. There was no wikipedia, no youtube, no streaming, and slow dial-up speeds. Besides the net, the main ways my teenage self had access to alternative music was triple j and Saturday nights spent staying up watching guest programmers on rage. It was probably a mixture of all these that led to me discovering what I am, for the purposes of this zine, lumping together as "early 90's Sydney indie pop". -

Jean-Michel Basquiat

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT Movimentos Artísticos Contemporâneos Índice Biografia : 03 Carreira : 05 Conceito : 09 Neo-expressionismo : 10 Primitivismo : 11 Técnicas : 12 Superficies : 13 Principais obras : 14 Exposições : 16 Legado : 18 Bibliografia : 20 Filmografia : 20 2 Biografia Jean-Michel Basquiat nasceu a 22 de Dezembro de 1960 em Brooklin, Nova Iorque. O seu pai nasceu no Haiti e a sua mãe era de origem Porto Riquenha. Bas- quiat era o mais velho de três filhos. Aos três anos de idade Basquiat já tinha começado a traçar caricaturas e tentava desenhar figuras do que percepcionava do quotidiano. A sua mãe sempre incentivou Basquiat a desenhar e a relacionar tudo com o mundo das Artes. Aos seis anos, Basquiat tinha como hábito visitar o Mu- seu de Arte Moderna por influência de sua mãe que o acompanhava. Aos sete anos teve um acidente em que o seu braço ficou gravemente magoado. Devido a este acontecimento, a sua mãe oferecera a Basquiat, durante a recuperação, o livro “Gray’s Anatomy”. 3 Esse mesmo livro foi o que o ajudou e influenciou nas suas representações humanas e posteriormente o livro também serviu de referência para a sua banda musi- cal formada em 1979, que deu pelo nome de “Gray’s” e durante algum tempo foi uma banda de sucesso. O divórcio de seus pais foi algo que o abalou muito na sua adolescência, levando-o a fugir muitas vezes de casa. Devido aos seus problemas familiares, em 1977 Basquiat é encaminhado para uma escola de crianças dotadas. 4 Carreira Nessa altura conhece Al Diaz e prospera a amizade entre os dois,criam juntos o projecto “SAMO”, com o significado “Same Old Shit”. -

Basquiat Boom for Real February 16 – May 27 2018

FILMING AND PHOTOGRAPHY – IMPORTANT GUIDELINES BASQUIAT BOOM FOR REAL FEBRUARY 16 – MAY 27 2018 Please ensure that you read and adhere to the following conditions: PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE EXHIBITION: IMPORTANT: Photography is not permitted in: o Sections “The Scene“, “Warhol“ and “Beat Bop“: no photography of any objects OR photography on loan from The Andy Warhol Foundation (see attached list) o Section “The Screen“: no photography of excerpt on TV „State of the Art“ o Section “Downtown 81“: Film “Downtown 81“ may only appear in background shots All images may only be used for current coverage of the exhibition. Their use for commercial purposes and the disclosure to third parties without further permission is prohibited. All works must be photographed in the context of the exhibition. No close up shots of individual works allowed. The images may not be changed in any significant way. All caption information must appear whenever an image is reproduced: Basquiat. Boom for Real Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt February 16 – May 27, 2018 Artworks: © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 & The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York. Press installation images are available from the Newsroom: http://www.schirn.de/en/m/press/newsroom/basquiat_boom_for_real/#images FILMING IN THE EXHIBITION IMPORTANT: Filming is not permitted in: o Sections “The Scene“, “Warhol“ and “Beat Bop“: no filming of any objects OR photography on loan from The Andy Warhol Foundation (see attached list) o Section “The Screen“: no filming of excerpt on TV „State of the Art“ o Section “Downtown 81“: Film “Downtown 81“ may only appear in background shots All recordings may only be used for current coverage of the exhibition.