In Search of Nirvana: Why Nirvana: the True Story Could Never Be'true'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

Find Artists Recent News

[LOGO] BROWSE LEARN LISTEN For Artists Search Log In / Register The Lumineers The LumineersThe Red Paintings The Red PaintingsThe So So Glos The So So Glos What Is PledgeMusic? Nam dapibus nisl vitae elit fringilla rutrum. Aenean sollicitudin, erat a elementum rutrum, neque sem pretium metus. Quis mollis nisl nunc et massa. Vestibulum sed metus in lorem tristique ullamcorper id vitae erat. Nulla mollis sapien sollicitudin lacinia lacinia. Vivamus facilisis dolor et massa placerat, at vestibulum nisl egestas. Lorem tristique Featured Artists Project Card Project Card Project Card Project Card Find Artists Placeholder Advanced Search Popular in Rock Project Card Project Card Project Card Project Card Recent News Older > 9/13 - Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit 9/10 - Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit 9/8 - Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Big Machine Showcase Project Card Project Card Project Card Project Card Browse Artists Browse Artists YOUR ACCOUNT CONNECT WITH US Learn About Pledge Learn About PledgeOrders Orders Listen to Music Listen to MusicSettings Settings Android Contact Contact Log Out Log Out Our team Our team FOR ARTISTS Careers Careers LAUNCH A PROJECT Blog Blog [LOGO] FeatureD Artists [Project CarD] [Project CarD] TrenDing this Week [Project CarD] [Project CarD] About PledgeMusic Vestibulum sed metus in lorem tristique ullamcorper id vitae erat. Nulla mollis sapien sollicitudin lacinia lacinia. Vivamus facilisis dolor et massa placerat, at vestibulum nisl egestas. [Music] [Updates] [Exclusive Items] [Personalized Recommendations] Recent News 9/13 - Lorem -

La Fugazi Live Series Sylvain David

Document generated on 10/01/2021 9:37 p.m. Sens public « Archive-it-yourself » La Fugazi Live Series Sylvain David (Re)constituer l’archive Article abstract 2016 Fugazi, one of the most respected bands of the American independent music scene, recently posted almost all of its live performances online, releasing over URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1044387ar 800 recordings made between 1987 and 2003. Such a project is atypical both by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1044387ar its size, rock groups being usually content to produce one or two live albums during the scope of their career, and by its perspective, Dischord Records, an See table of contents independent label, thus undertaking curatorial activities usually supported by official cultural institutions such as museums, libraries and universities. This approach will be considered here both in terms of documentation, the infinite variations of the concerts contrasting with the arrested versions of the studio Publisher(s) albums, and of the musical canon, Fugazi obviously wishing, by the Département des littératures de langue française constitution of this digital archive, to contribute to a parallel rock history. ISSN 2104-3272 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article David, S. (2016). « Archive-it-yourself » : la Fugazi Live Series. Sens public. https://doi.org/10.7202/1044387ar Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) Sens-Public, 2016 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

A Case Study of Kurt Donald Cobain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) A CASE STUDY OF KURT DONALD COBAIN By Candice Belinda Pieterse Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University December 2009 Supervisor: Prof. J.G. Howcroft Co-Supervisor: Dr. L. Stroud i DECLARATION BY THE STUDENT I, Candice Belinda Pieterse, Student Number 204009308, for the qualification Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology, hereby declares that: In accordance with the Rule G4.6.3, the above-mentioned treatise is my own work and has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. Signature: …………………………………. Date: …………………………………. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several individuals that I would like to acknowledge and thank for all their support, encouragement and guidance whilst completing the study: Professor Howcroft and Doctor Stroud, as supervisors of the study, for all their help, guidance and support. As I was in Bloemfontein, they were still available to meet all my needs and concerns, and contribute to the quality of the study. My parents and Michelle Wilmot for all their support, encouragement and financial help, allowing me to further my academic career and allowing me to meet all my needs regarding the completion of the study. The participants and friends who were willing to take time out of their schedules and contribute to the nature of this study. Konesh Pillay, my friend and colleague, for her continuous support and liaison regarding the completion of this study. -

A Denial the Death of Kurt Cobain the Seattle Police Department

A Denial The Death of Kurt Cobain The Seattle Police Department Substandard Investigation & The Repercussions to Justice by Bree Donovan A Capstone Submitted to The Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University, New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies Under the direction of Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo and approved by _________________________________ Capstone Director _________________________________ Program Director Camden, New Jersey, December 2014 i Abstract Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) musician, artist songwriter, and founder of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band, Nirvana, was dubbed, “the voice of a generation”; a moniker he wore like his faded cardigan sweater, but with more than some distain. Cobain‟s journey to the top of the Billboard charts was much more Dickensian than many of the generations of fans may realize. During his all too short life, Cobain struggled with physical illness, poverty, undiagnosed depression, a broken family, and the crippling isolation and loneliness brought on by drug addiction. Cobain may have shunned the idea of fame and fortune but like many struggling young musicians (who would become his peers) coming up in the blue collar, working class suburbs of Aberdeen and Tacoma Washington State, being on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine wasn‟t a nightmare image. Cobain, with his unkempt blond hair, polarizing blue eyes, and fragile appearance is a modern-punk-rock Jesus; a model example of the modern-day hero. The musician- a reluctant hero at best, but one who took a dark, frightening journey into another realm, to emerge stronger, clearer headed and changing the trajectory of his life. -

Download PDF > Riot Grrrl \\ 3Y8OTSVISUJF

LWSRQOQGSW3L / Book ~ Riot grrrl Riot grrrl Filesize: 8.18 MB Reviews Unquestionably, this is actually the very best work by any article writer. It usually does not price a lot of. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Augustine Pfannerstill) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GOKP10TMWQNH / Kindle ~ Riot grrrl RIOT GRRRL To download Riot grrrl PDF, make sure you refer to the button under and download the document or gain access to other information which might be related to RIOT GRRRL book. Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 54. Chapters: Kill Rock Stars, Sleater-Kinney, Tobi Vail, Kathleen Hanna, Lucid Nation, Jessicka, Carrie Brownstein, Kids Love Lies, G. B. Jones, Sharon Cheslow, The Shondes, Jack O Jill, Not Bad for a Girl, Phranc, Bratmobile, Fih Column, Caroline Azar, Bikini Kill, Times Square, Jen Smith, Nomy Lamm, Huggy Bear, Karen Finley, Bidisha, Kaia Wilson, Emily's Sassy Lime, Mambo Taxi, The Yo-Yo Gang, Ladyfest, Bangs, Shopliing, Mecca Normal, Voodoo Queens, Sister George, Heavens to Betsy, Donna Dresch, Allison Wolfe, Billy Karren, Kathi Wilcox, Tattle Tale, Sta-Prest, All Women Are Bitches, Excuse 17, Pink Champagne, Rise Above: The Tribe 8 Documentary, Juliana Luecking, Lungleg, Rizzo, Tammy Rae Carland, The Frumpies, Lisa Rose Apramian, List of Riot Grrl bands, 36-C, Girl Germs, Cold Cold Hearts, Frightwig, Yer So Sweet, Direction, Viva Knievel. Excerpt: Riot grrrl was an underground feminist punk movement based in Washington, DC, Olympia, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and the greater Pacific Northwest which existed in the early to mid-1990s, and it is oen associated with third-wave feminism (it is sometimes seen as its starting point). -

The Sociology of Youth Subcultures

Peace Review 16:4, December (2004), 409-4J 4 The Sociology of Youth Subcultures Alan O'Connor The main theme in the sociology of youth subcultures is the reladon between social class and everyday experience. There are many ways of thinking about social class. In the work of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu the main factors involved are parents' occupation and level of education. These have signilicant effects on the life chances of their children. Social class is not a social group: the idea is not that working class kids or middle class kids only hang out together. There may be some of this in any school or town. Social class is a structure. It is shown to exist by sociological research and many people may only be partly aware of these structures or may lack the vocabulary to talk about them. It is often the case that people blame themselves—their bad school grades or dead-end job—for what are, at least in part, the effects of a system of social class that has had significant effects on their lives. The main point of Bourdieu's research is to show that many kids never had a fair chance from the beginning. n spite of talk about "globalizadon" there are significant differences between Idifferent sociedes. Social class works differently in France, Mexico and the U.S. For example, the educadon system is different in each country. In studying issues of youth culture, it is important to take these differences into account. The system of social class in each country is always experienced in complex ways. -

Charles Peterson …And Everett True Is 481

Dwarves Photos: Charles Peterson …and Everett True is 481. 19 years on from his first Seattle jolly on the Sub Pop account, Plan B’s publisher-at-large jets back to the Pacific Northwest to meet some old friends, exorcise some ghosts and find out what happened after grunge left town. How did we get here? Where are we going? And did the Postal Service really sell that many records? Words: Everett True Transcripts: Natalie Walker “Heavy metal is objectionable. I don’t even know comedy genius, the funniest man I’ve encountered like, ‘I have no idea what you’re doing’. But he where that [comparison] comes from. People will in the Puget Sound8. He cracks me up. No one found trusted the four of us enough to let us go into the say that Motörhead is a metal band and I totally me attractive until I changed my name. The name studio for a weekend and record with Jack. It was disagree, and I disagree that AC/DC is a metal band. slides into meaninglessness. What is the Everett True essentially a demo that became our first single.” To me, those are rock bands. There’s a lot of Chuck brand in 2008? What does Sub Pop stand for, more Berry in Motörhead. It’s really loud and distorted and than 20 years after its inception? Could Sub Pop It’s in the focus. The first time I encountered Sub amplified but it’s there – especially in the earlier have existed without Everett True? Could Everett Pop, I had 24 hours to write up my first cover feature stuff. -

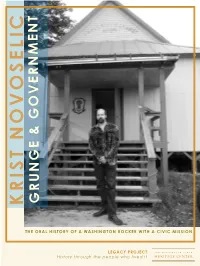

Krist Novoselic

OVERNMENT G & E GRUNG KRIST NOVOSELIC THE ORAL HISTORY OF A WASHINGTON ROCKER WITH A CIVIC MISSION LEGACY PROJECT History through the people who lived it Krist Novoselic Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes October 14, 2008 John Hughes: This is October 14, 2008. I’m John Hughes, Chief Oral Historian for the Washington State Legacy Project, with the Offi ce of the Secretary of State. We’re in Deep River, Wash., at the home of Krist Novoselic, a 1984 graduate of Aberdeen High School; a founding member of the band Nirvana with his good friend Kurt Cobain; politi cal acti vist, chairman of the Wahkiakum County Democrati c Party, author, fi lmmaker, photographer, blogger, part-ti me radio host, While doing reseach at the State Archives in 2005, Novoselic volunteer disc jockey, worthy master of the Grays points to Grays River in Wahkiakum County, where he lives. Courtesy Washington State Archives River Grange, gentleman farmer, private pilot, former commercial painter, ex-fast food worker, proud son of Croati a, and an amateur Volkswagen mechanic. Does that prett y well cover it, Krist? Novoselic: And chairman of FairVote to change our democracy. Hughes: You know if you ever decide to run for politi cal offi ce, your life is prett y much an open book. And half of it’s on YouTube, like when you tried for the Guinness Book of World Records bass toss on stage with Nirvana and it hits you on the head, and then Kurt (Cobain) kicked you in the butt . -

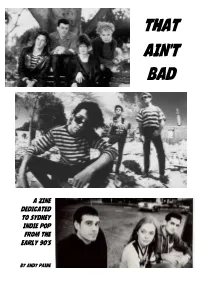

That Ain't Bad (The Main Single Off Tingles), the Band Are Drowned out by the Crowd Singing Along

THAT AIN’T BAD A ZINE DEDICATED TO SYDNEY INDIE POP FROM THE EARLY 90’S BY ANDY PAINE INTROduction In the late 1980's and early 1990's, a group of bands emerged from Sydney who all played fuzzy distorted guitars juxtaposed with poppy melodies and harmonies. They released some wonderful music, had a brief period of remarkable mainstream success, and then faded from the memory of Australia's 'alternative' music world. I was too young to catch any of this music the first time around – by the time I heard any of these bands the 90’s were well and truly over. It's hard to say how I first heard or heard about the bands in this zine. As a teenage music nerd I devoured the history of music like a mechanical harvester ploughing through a field of vegetables - rarely pausing to stop and think, somethings were discarded, some kept with you. I discovered music in a haphazard way, not helped by living in a country town where there were few others who shared my passion for obscure bands and scenes. The internet was an incredible resource, but it was different back then too. There was no wikipedia, no youtube, no streaming, and slow dial-up speeds. Besides the net, the main ways my teenage self had access to alternative music was triple j and Saturday nights spent staying up watching guest programmers on rage. It was probably a mixture of all these that led to me discovering what I am, for the purposes of this zine, lumping together as "early 90's Sydney indie pop". -

'Race Riot' Within and Without 'The Grrrl One'; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines

The ‘Race Riot’ Within and Without ‘The Grrrl One’; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines’ Tactical Construction of Space by Addie Shrodes A thesis presented for the B. A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2012 © March 19, 2012 Addie Cherice Shrodes Acknowledgements I wrote this thesis because of the help of many insightful and inspiring people and professors I have had the pleasure of working with during the past three years. To begin, I am immensely indebted to my thesis adviser, Prof. Gillian White, firstly for her belief in my somewhat-strange project and her continuous encouragement throughout the process of research and writing. My thesis has benefitted enormously from her insightful ideas and analysis of language, poetry and gender, among countless other topics. I also thank Prof. White for her patient and persistent work in reading every page I produced. I am very grateful to Prof. Sara Blair for inspiring and encouraging my interest in literature from my first Introduction to Literature class through my exploration of countercultural productions and theories of space. As my first English professor at Michigan and continual consultant, Prof. Blair suggested that I apply to the Honors program three years ago, and I began English Honors and wrote this particular thesis in a large part because of her. I owe a great deal to Prof. Jennifer Wenzel’s careful and helpful critique of my thesis drafts. I also thank her for her encouragement and humor when the thesis cohort weathered its most chilling deadlines. I am thankful to Prof. Lucy Hartley, Prof. -

Nightlight: Tradition and Change in a Local Music Scene

NIGHTLIGHT: TRADITION AND CHANGE IN A LOCAL MUSIC SCENE Aaron Smithers A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Curriculum of Folklore. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Glenn Hinson Patricia Sawin Michael Palm ©2018 Aaron Smithers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Aaron Smithers: Nightlight: Tradition and Change in a Local Music Scene (Under the direction of Glenn Hinson) This thesis considers how tradition—as a dynamic process—is crucial to the development, maintenance, and dissolution of the complex networks of relations that make up local music communities. Using the concept of “scene” as a frame, this ethnographic project engages with participants in a contemporary music scene shaped by a tradition of experimentation that embraces discontinuity and celebrates change. This tradition is learned and communicated through performance and social interaction between participants connected through the Nightlight—a music venue in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Any merit of this ethnography reflects the commitment of a broad community of dedicated individuals who willingly contributed their time, thoughts, voices, and support to make this project complete. I am most grateful to my collaborators and consultants, Michele Arazano, Robert Biggers, Dave Cantwell, Grayson Currin, Lauren Ford, Anne Gomez, David Harper, Chuck Johnson, Kelly Kress, Ryan Martin, Alexis Mastromichalis, Heather McEntire, Mike Nutt, Katie O’Neil, “Crowmeat” Bob Pence, Charlie St. Clair, and Isaac Trogden, as well as all the other musicians, employees, artists, and compatriots of Nightlight whose combined efforts create the unique community that define a scene.