Utilizing the Works of Michel De Certeau to Analyze Coping Mechanisms and Overt Forms of Resistance Among Glass Workers in Huntington, West Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Toolkit for Working with the Media

Utilizing the Media to Facilitate Social Change A Toolkit for Working with the Media WEST VIRGINIA FOUNDATION for RAPE INFORMATION and SERVICES www.fris.org 2011 Media Toolkit | 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Media Advocacy……………………………….. ……….. 3 Building a Relationship with the Media……... ……….. 3 West Virginia Media…………………………………….. 4 Tips for Working with the Media……………... ……….. 10 Letter to the Editor…………………………….. ……….. 13 Opinion Editorial (Op-Ed)…………………….. ……….. 15 Media Advisory………………………………… ……….. 17 Press/News Release………………………….. ……….. 19 Public Service Announcements……………………….. 21 Media Interviews………………………………. ……….. 22 Survivors’ Stories and the Media………………………. 23 Media Packets…………………………………. ……….. 25 Media Toolkit | 3 Media Advocacy Media advocacy can promote social change by influencing decision-makers and swaying public opinion. Organizations can use mass media outlets to change social conditions and encourage political and social intervention. When working with the media, advocates should ‘shape’ their story to incorporate social themes rather than solely focusing on individual accountability. “Develop a story that personalizes the injustice and then provide a clear picture of who is benefiting from the condition.” (Wallack et al., 1999) Merely stating that there is a problem provides no ‘call to action’ for the public. Therefore, advocates should identify a specific solution that would allow communities to take control of the issue. Sexual violence is a public health concern of social injustices. Effective Media Campaigns Local, regional or statewide campaigns can provide a forum for prevention, outreach and raising awareness to create social change. This toolkit will enhance advocates’ abilities to utilize the media for campaigns and other events. Campaigns can include: public service announcements (PSAs), awareness events (Take Back the Night; The Clothesline Project), media interviews, coordinated events at area schools or college campuses, position papers, etc. -

The Parthenon, April 3, 2013

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The aP rthenon University Archives 4-3-2013 The aP rthenon, April 3, 2013 John Gibb [email protected] Tyler Kes [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Gibb, John and Kes, Tyler, "The aP rthenon, April 3, 2013" (2013). The Parthenon. Paper 207. http://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/207 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP rthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C M Y K 50 INCH SPJ lecture focuses on black history, life of an African-American scholar > More on News WEDNESDAY, APRIL 3, 2013 | VOL. 116 NO. 111 | MARSHALL UNIVERSITY’S STUDENT NEWSPAPER | marshallparthenon.com Manchin visits Marshall, discusses social issues with students By CAITLIN KINDER-MUNDAY you can eliminate and what you Manchin discussed multiple THE PARTHENON can’t eliminate.” social issues brought up by stu- Senator Joe Manchin visited Manchin used the example of dents in attendance. Marshall University Tuesday to comparing individual students Medicare was one issue discuss multiple social issues brought up by a student in the that were on student’s minds. the government as a whole. The room. Manchin discussed how At 4 p.m., around 70 students governmentoperating on maintains a fixed income a much to quickly Medicare funds are go- and faculty members gathered larger budget, but accrues ing to run out if the government in Room 336 of Smith Hall to much more debt as well. -

Marshall Quick Facts Quick Facts the University Coaching Staff Location ______Huntington, W.Va

Marshall Quick Facts Quick Facts The University Coaching Staff Location ___________________________________________Huntington, W.Va. NAME POSITION YEAR AT MARSHALL Founded __________________________________ 1837 (as Marshall Academy) Mark Snyder Head Coach 5th Enrollment __________________________________________________ 13,814 Jeff Burrow Assistant Secondary 1st Nickname ________________________________ Thundering Herd or the Herd Mike Cummings Off ensive Line/Recruiting 5th Colors _____________________________________ Green (PMS 357) and White Mike Cassity Secondary 1st Stadium ______________________________________Joan C. Edwards Stadium Bob Fello Defensive Line 1st Capacity ____________________________________________________ 38,019 Todd Goebbel Receivers 5th Year Opened _______________________ 1991 (as Marshall University Stadium) Phil Ratliff Tight Ends 4th Surface ________________________________FieldTurf (installed August 2006) Rick Minter Defensive Coordinator 2nd Affi liation __________________________________________NCAA Division I-A John Shannon Off ensive Coordinator 2nd Conference ______________________________ Conference USA (East Division) Jared Smith Running Backs 5th President _________________________Dr. Stephen J. Kopp (Notre Dame, 1973) Mark Gale Assistant AD/Football Operations 20th School Website _____________________________________ www.Marshall.edu Edna Justice Program Assistant 30th Athletics Website _________________________________ www.HerdZone.com Facebook__________________________________ Marshall University -

2006 Media Guide.Indd

2 2006-07 Quick Facts Marshall University 0 Location ..................................................................................Huntington, W.Va. 0 Founded ...........................................................................................................1837 6 Enrollment ....................................................................................................16,531 - Nickname ................................................................................ Thundering Herd 0 Colors ............................................................................................Green & White 7 Conference ................................................................................ Conference USA Q National Affi liation .................................................................NCAA Division I u Home Arena .....................................................Cam Henderson Center (9,043) i c President ..............................................Dr. Stephen J. Kopp (Notre Dame, ‘73) k Athletic Director ...................................................Bob Marcum (Marshall, ‘58) Associate A.D. ...........................................................Jeff O’Malley (Miami, ‘90) F a Associate A.D. ...................................Beatrice Crane Banford (N.C. State, ‘92) c Associate A.D. ................................................................David Steele (Rice, ‘82) t Associate A.D. .................................................Scott Morehouse (Marshall, ‘98) s Associate A.D. ..............................................David -

Wmul/Travel Information

WMUL/TRAVEL INFORMATION 113 Dr. Stephen J. Kopp, former special assistant to the chancellor with the Ohio Board of Regents, and former provost of Ohio University, is MU PRESIDENT DR. STEPHEN J. KOPP Marshall University’s 36th president. He was named president by Marshall’s Board of Governors in June 2005. “Looking at Marshall and the Huntington community, I have been so impressed with the tremendous relationship between the two,” Kopp says. “That support base, not just in Huntington but in the state as a whole, is a tremendously strong foundation for building a vibrant future for Marshall University, and helping the community and the surrounding area improve the quality of life for West Virginians. To be a part of that, to work with the community to help that transition take place, is an incredibly exciting opportunity.” Kopp speaks often of the “promise of a better future” for West Virginians, and says an important part of fulfi lling that promise is a solid com- Stephen J. Kopp mitment to advance student learning. President “We need to produce learning that makes a difference in the lives of our students and the communities that they are a part of,” Kopp says. “It’s a process that involves the entire campus community. How can we improve the achievement of the students? We need to push ourselves to get better and better.” Kopp and his wife, Jane, have two grown children. Their son, Adam, lives in Chicago and works in the law of- fi ce of the Illinois lieutenant governor. Their daughter, Elizabeth, a physical therapist, and her husband, Mat- thew Bradley, M.D., an orthopedic resident, live in Portland, Ore., and are the proud parents of the Kopp’s fi rst grandchild, Rachel. -

Marshall University News Letter, February 6, 1981 Office Ofni U Versity Relations

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Marshall University News Letter 1972-1986 Marshall Publications 2-6-1981 Marshall University News Letter, February 6, 1981 Office ofni U versity Relations Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/oldmu_news_letter Recommended Citation Office of University Relations, "Marshall University News Letter, February 6, 1981" (1981). Marshall University News Letter 1972-1986. Paper 501. http://mds.marshall.edu/oldmu_news_letter/501 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marshall Publications at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marshall University News Letter 1972-1986 by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. MU faculty and staff achievements, activities . .. 'STOCKHOLDERS' AT MARSHALL WILLIAM J. RADIG, assistant professor of accounting, SEC as True Master," will be presented by Madison and A gift of 500 shares of Van Dorn is the author of "I RS Access to Taxpayers' Records" to Balsmeier at the Southwest Regional Meeting of the Co. stock from 101-year-old Lemot be published in the Winter 1981 edition of The Ohio CPA American Accounting Association in New Orleans in to Smith of Miami Beach, Fla., is Journal. March. The paper was selected for publication in the proceedings of the meeting. presented to the Marshall Univer DR. WILLIAM SCHNEIDERMAN, assistant professor sity Foundation by MU alumnus of psychology, is the author of "Implications of Pro DR. JOSEPH S. LaCASCIA, professor and Economics Edward Goodno of Huntington, cedural Variation for Replication Research," to be Department chairman, spoke on "The U.S. -

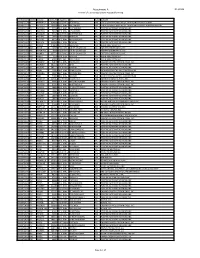

Attachment a DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing

Attachment A DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing File Number Service Callsign Facility ID Frequency City State Licensee 0000072254 FL WMVK-LP 124828 107.3 MHz PERRYVILLE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMN. 0000072255 FL WTTZ-LP 193908 93.5 MHz BALTIMORE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 0000072258 FX W253BH 53096 98.5 MHz BLACKSBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072259 FX W247CQ 79178 97.3 MHz LYNCHBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072260 FX W264CM 93126 100.7 MHz MARTINSVILLE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072261 FX W279AC 70360 103.7 MHz ROANOKE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072262 FX W243BT 86730 96.5 MHz WAYNESBORO VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072263 FX W241AL 142568 96.1 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072265 FM WVRW 170948 107.7 MHz GLENVILLE WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072267 AM WESR 18385 1330 kHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072268 FM WESR-FM 18386 103.3 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072270 FX W289CE 157774 105.7 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072271 FM WOTR 1103 96.3 MHz WESTON WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072274 AM WHAW 63489 980 kHz LOST CREEK WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072285 FX W206AY 91849 89.1 MHz FRUITLAND MD CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. 0000072287 FX W284BB 141155 104.7 MHz WISE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072288 FX W295AI 142575 106.9 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072293 FM WXAF 39869 90.9 MHz CHARLESTON WV SHOFAR BROADCASTING CORPORATION 0000072294 FX W204BH 92374 88.7 MHz BOONES MILL VA CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. -

List of Radio Stations in West Virginia

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in West Virginia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of FCC-licensed radio stations in the U.S. state of West Virginia, which can Contents be sorted by their call signs, frequencies, cities of license, licensees, and programming formats. Featured content Current events Contents [hide] Random article 1 List of radio stations Donate to Wikipedia 2 Defunct Wikipedia store 3 See also 4 References Interaction 5 Bibliography Help 6 External links About Wikipedia 7 Images Community portal Recent changes Contact page List of radio stations [edit] Tools This list is complete and up to date as of December 17, 2018. What links here Related changes Call City of [2][3] [4] Upload file Frequency Licensee Format sign License [1][2] Special pages open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Permanent link Princeton Broadcasting, WAEY 1490 AM Princeton Southern gospel Page information Inc. Wikidata item Webster Cite this page WAFD 100.3 FM Summit Media, Inc. Hot adult contemporary Springs Print/export WAGE- Southern Appalachian 106.5 FM Oak Hill Variety Create a book LP Labor School Download as PDF West Virginia Radio Printable version WAJR 1440 AM Morgantown News/Talk/Sports Corporation In other projects WAJR- West Virginia Radio 103.3 FM Salem News/Talk/Sports Wikimedia Commons FM Corporation of Salem Languages West Virginia – Virginia WAMN 1050 AM Green Valley Classic country Add links Media, LLC WAMX 106.3 FM Milton Capstar TX LLC Classic rock WASP- Spring Valley High 104.5 FM Huntington Variety LP School (Students) WAXE- Coal Mountain 106.9 FM St. -

King's Daughters Medical Center, 606-408-9340

King’s Daughters Medical Center Community Health Needs Assessment 2016 Serving Boyd, Greenup, Carter Counties in Kentucky and Lawrence County, Ohio 1 2 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………….5 2. Facility Description……………………………………………………………………….6 3. Description of Community Served…………………………………………………8 4. Process and Methodology……………………………………………………………..9 5. Community Advisory Board…………………………………………………………11 6. Primary Data Collection……………………………………………………………….12 7. Secondary Data Collection…………………………………………………………..17 8. Information Gaps…………………………………………………………………………26 9. Existing Resources……………………………………………………………………….26 10. Community Assets…………………………………………………………………….28 11. Health Needs Identified…………………………………………………………….28 12. Priorities……………………………………………………………………………………29 13. Appendix……………………………………………………………………………………40 A. Community Forum Results B. Survey Results C. Community Feedback Press Release D. KinG’s DauGhters 2015 Community Report 3 4 Executive Summary King’s Daughters Medical Center is a locally controlled, not-for-profit, 465 bed regional referral center, covering a 150 mile radius that includes southern Ohio and eastern Kentucky. With more than 3,000 team members, King’s Daughters offers comprehensive cardiac, medical, surgical, maternity, pediatric, rehabilitative, bariatric, psychiatric, cancer, neurological, pain care, wound care and home care services. KDMC operates more than 50 offices in eastern Kentucky and southern Ohio. King’s Daughters conducted a Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) with Bon Secours Kentucky, Our Lady of Bellefonte Hospital between September 2015 and March 2016. The CHNA included both primary data analysis and secondary data analysis. The primary data encompassed surveys and focus groups with key individuals in the community including those representatives of our community with knowledge of public health, the broad interests of the communities we serve, as well as individuals with special knowledge of the medically underserved, low-income and vulnerable populations and people with chronic diseases. -

Policies and Station Organization

Policies and Station Organization Volume I of The WMUL-FM Operations Manual Policies and Station Organization Volume I of The WMUL-FM Operations Manual -by: Charles G. Bailey, Ed.D., Mark DiIorio, and Michael Stanley For Students, Staff, Faculty, and Community Volunteers Participating in the Operation and Programming of Radio Station WMUL-FM 88.1 MHz Marshall University One John Marshall Drive Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2635 (304) 696-6640 July 2016 Edition Dedicated to Nathan B. Stubblefield and the other pioneers whose dreams became radio. “If I see farther, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” — Sir Issac Newton This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ A version of this work with a NonCommercial-ShareAlike (NC-SA) license is available. See WMUL-FM’s website. www.marshall.edu/wmul/ Part 3, Chapter G, Sections 1 and 2 are adapted from FCC Information Bulletin “EB-18FM” “FM BROADCAST STATION SELF - INSPECTION CHECKLIST” June 2008 Edition, Updated September 1, 2009. Some glossary definitions (Part 16) are taken from Modern Radio Production: Production, Programming, and Performance Tenth Edition Hausman, Messere, Benoit, and O’Donnell Cover photo originally by Thomas Kelley unsplash.com/@thkelley and was published under a CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication Part 1 header photo (page 0) by Braxton Crisp. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.A. Using This Volume 1 1.B. Using This Manual 2 1.C. WMUL-FM Radio 4 1.D. Floor Plan of WMUL-FM 5 1.E. -

Marshall Magazine Autumn 2014 Marshall University

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Marshall Magazine Marshall Publications Fall 2014 Marshall Magazine Autumn 2014 Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/marshall_magazine Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Marshall University, "Marshall Magazine Autumn 2014" (2014). Marshall Magazine. Book 9. http://mds.marshall.edu/marshall_magazine/9 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Marshall Publications at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marshall Magazine by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The return of Thundering Herd football General Anthony Crutchfield From Marshall University to the U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM) See page 37 for ALUMNI NEWS and more Autumn 2014 www.marshall.edu Marshall President Stephen Kopp Senior Vice President for Communications and Marketing Ginny Painter Executive Editor Marshallmagazine Susan Tams The official magazine of Marshall University Director of Communications Dave Wellman Autumn 2014 Publisher Jack Houvouras Managing Editor features Rebecca Stephens Art Director 4 Marshall alumnus Anthony Crutchfield takes Jenette Williams on new role as Lieutenant General. Graphic Designer Rachel Moyer 12 New indoor athletic facility puts the Herd ahead of the game. Contributing Photographers Rick Haye, Rick Lee 18 Marshall football’s fall lineup promises Contributing Writers an exciting season for fans. James E. Casto Molly McClennen Keith Morehouse Collaboration between two professors leads 24 Dawn Nolan to new findings in the fight against cancer. Ruth Rose 30 Visual Arts Center expected to boost education Alumni Editor in the heart of downtown Huntington. -

Bookstore May Be Private• by Fall

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The Parthenon University Archives 2-8-1995 The Parthenon, February 8, 1995 Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Marshall University, "The Parthenon, February 8, 1995" (1995). The Parthenon. 3352. https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/3352 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Parthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Feb. a, 1995 MARSHALL UNIVERSITY WEDNESDAY Cloudy, 50 percent chance of snow High upper 20s Page edited by L8q1 A.. S• lbe, 696-6696 • EMPLOYaE CONCERNS Bookstore may be private •by fall By Brian Hofmann people to say how they would run things.. What we ment private, or making the whole operation private. Reporter want them to do is say, 'Ifwe ran your boobtore, this ,Denman said Gilley chose to make the whole is how we would do it.'" operation private. This upset some bookstore The Marshall University Bookstore may be in Denman said the committee is moving slowly to get employees, who said they don't want to see a private private hands as soon as the fall semester, Dr. the necessary items in the contract while attempting company come in. William Denman, the chairman of the committee to get private ownership as soon as possible. Shannon Harshbarger, supervisor ofthe bookstore, looking into bookstore operations said Monday. Controller Ted W. Massey, another committee said he would have preferred the committee follow Denman, chairman of the Department of member, said the group wants to make sure employ what the NACS group recommended, which was Communication Studies, said the committee wants ees can stay with the store.