Narration in Gebreyesus Hailu's the Conscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE WRITINGS of BRITISH CONSCRIPT SOLDIERS, 1916-1918 Ilana Ruth Bet-El Submitted for the Degree of Ph

EXPERIENCE INTO IDENTITY: THE WRITINGS OF BRITISH CONSCRIPT SOLDIERS, 1916-1918 Ilana Ruth Bet-El Submitted for the degree of PhD University College London AB STRACT Between January 1916 and March 1919 2,504,183 men were conscripted into the British army -- representing as such over half the wartime enlistments. Yet to date, the conscripts and their contribution to the Great War have not been acknowledged or studied. This is mainly due to the image of the war in England, which is focused upon the heroic plight of the volunteer soldiers on the Western Front. Historiography, literary studies and popular culture all evoke this image, which is based largely upon the volumes of poems and memoirs written by young volunteer officers, of middle and upper class background, such as Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. But the British wartime army was not a society of poets and authors who knew how to distil experience into words; nor, as mentioned, were all the soldiers volunteers. This dissertation therefore attempts to explore the cultural identity of this unknown population through a collection of diaries, letters and unpublished accounts of some conscripts; and to do so with the aid of a novel methodological approach. In Part I the concept of this research is explained, as a qualitative examination of all the chosen writings, with emphasis upon eliciting the attitudes of the writers to the factual events they recount. Each text -- e.g. letter or diary -- was read literally, and also in light of the entire collection, thus allowing for the emergence of personal and collective narratives concurrently. -

Napoleon's Men

NAPOLEON S MEN This page intentionally left blank Napoleon's Men The Soldiers of the Revolution and Empire Alan Forrest hambledon continuum Hambledon Continuum The Tower Building 11 York Road London, SE1 7NX 80 Maiden Lane Suite 704 New York, NY 10038 First Published 2002 in hardback This edition published 2006 ISBN 1 85285 269 0 (hardback) ISBN 1 85285 530 4 (paperback) Copyright © Alan Forrest 2002 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyrights reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book. A description of this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress. Typeset by Carnegie Publishing, Lancaster, and printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Cornwall. Contents Illustrations vii Introduction ix Acknowledgements xvii 1 The Armies of the Revolution and Empire 1 2 The Soldiers and their Writings 21 3 Official Representation of War 53 4 The Voice of Patriotism 79 5 From Valmy to Moscow 105 6 Everyday Life in the Armies 133 7 The Lure of Family and Farm 161 8 From One War to Another 185 Notes 205 Bibliography 227 Index 241 This page intentionally left blank Illustrations Between pages 108 and 109 1 Napoleon Bonaparte, crossing the Alps in 1800 2 Volunteers enrolling 3 Protesting -

The Ottoman Home Front During World War I: Everyday Politics, Society, and Culture

The Ottoman Home Front during World War I: Everyday Politics, Society, and Culture Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yiğit Akın Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Carter V. Findley, Advisor Jane Hathaway David L. Hoffman Copyright by Yiğit Akın 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to examine the socio-economic and cultural dimensions of the home-front experience of the Ottoman people during World War I. It explores the new realities that the war created in the form of mass conscription, a state-controlled economy, government requisitioning of grain and possessions, widespread shortages, forcible deportations and voluntary displacements, death, and grief. Using archival and non-archival sources, it also focuses on how Ottomans wrestled with these wartime realities. World War I required the most comprehensive mobilization of men and resources in the history of the Ottoman Empire. In order to wage a war of unprecedented scope effectively, the Ottoman government assumed new powers, undertook new responsibilities, and expanded its authority in many areas. Civilian and military authorities constantly experimented with new policies in order to meet the endless needs of the war and extended the state’s capacity to intervene in the distant corners of the empire to extract people and resources to a degree not seen before. Victory in the war became increasingly dependent on the successful integration of the armies in the field and the home-front population, a process that inescapably led to the erosion of the distinction between the military and civilian realms. -

World War II Comes to the Northern Plains Observing the 75Th Anniversary of America’S Entrance Into World War II (1941—2016)

World War II Comes to the Northern Plains Observing the 75th Anniversary of America’s Entrance Into World War II (1941—2016) Papers of the Forty-Eighth Annual DAKOTA CONFERENCE A National Conference on the Northern Plains Photo credit: Glenn E. Soladay PhoCollection, Center for Western Studies THE CENTER FOR WESTERN STUDIES AUGUSTANA UNIVERSITY 2016 World War II Comes to the Northern Plains Observing the 75th Anniversary of America’s Entrance Into World War II (1941—2016) Papers of the Forty-Eighth Annual Dakota Conference A National Conference on the Northern Plains The Center for Western Studies Augustana University Sioux Falls, South Dakota April 22-23, 2016 Compiled by: Kari Mahowald Financial Contributors Loren and Mavis Amundson CWS Endowment/SFACF City of Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission Joe and Bobbi Jo Dondelinger Carol Rae Hansen, Andrew Gilmour & Grace Hansen-Gilmour Endowment Gordon and Trudy Iseminger Joan and Jerry Jencks Mellon Fund Committee of Augustana University Rex Myers & Susan Richards Endowment Joyce Nelson, in Memory of V.R. Nelson Rollyn H. Samp Endowment, in Honor of Ardyce Samp Roger & Shirley Schuller, in Honor of Matthew Schuller Glenn E. Soladay Estate (in Honor of Those Who Served in the 147th Field Artillery Regiment) Blair & Linda Tremere Richard & Michelle Van Demark James & Penny Volin Cover photo credit: Glenn E. Soladay Collection, Center for Western Studies Table of Contents Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………v Aronson, Dr. Marilyn Carlson World War II Comes to South Dakota—Preserving the Story…………….………………….….1 Benson, Bob Addie…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…21 Browne, Miles A. The War Comes to 205 North Hawthorne……………..……………………………………………....24 Buntin, Arthur From Draftee to Soldier: The Educational Journey of a Montana Teenager, 1941-1946………………………………………………………………………………………………………………31 Buntin, Arthur The European War: Editorial Attitudes of the Aberdeen American News, 1939-1941……………………………………………………………………………………………………..………45 Christopherson, Stan A. -

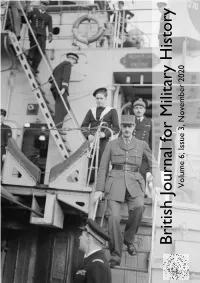

Volum E 6, Issue 3, November 2020

www.bjmh.org.uk British Journal for Military History Volume 6, Issue 3, November 2020 Cover photo: Visit of General De Gaulle and Admiral Muselier to a naval port. 1940, The head of the Free French Forces, General Charles De Gaulle, accompanied by Admiral Muselier, visited French ships manned by members of the Free French Naval Forces at a British port. On board the French sloop La Moquese. Photo © Imperial War Museum A 2172 www.bjmh.org.uk BRITISH JOURNAL FOR MILITARY HISTORY EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD The Editorial Team gratefully acknowledges the support of the British Journal for Military History’s Editorial Advisory Board the membership of which is as follows: Chair: Prof Alexander Watson (Goldsmiths, University of London, UK) Dr Laura Aguiar (Public Record Office of Northern Ireland / Nerve Centre, UK) Dr Andrew Ayton (Keele University, UK) Prof Tarak Barkawi (London School of Economics, UK) Prof Ian Beckett (University of Kent, UK) Dr Huw Bennett (University of Cardiff, UK) Prof Martyn Bennett (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Dr Matthew Bennett (University of Winchester, UK) Dr Philip W. Blood (Member, BCMH, UK) Prof Brian Bond (King’s College London, UK) Dr Timothy Bowman (University of Kent, UK; Member BCMH, UK) Ian Brewer (Treasurer, BCMH, UK) Dr Ambrogio Caiani (University of Kent, UK) Prof Antoine Capet (University of Rouen, France) Dr Erica Charters (University of Oxford, UK) Sqn Ldr (Ret) Rana TS Chhina (United Service Institution of India, India) Dr Gemma Clark (University of Exeter, UK) Dr Marie Coleman (Queens University -

![Laus Ululae. the Praise of Owls. an Oration to the Conscript Fathers, and Patrons of Owls [Commentary]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3880/laus-ululae-the-praise-of-owls-an-oration-to-the-conscript-fathers-and-patrons-of-owls-commentary-12883880.webp)

Laus Ululae. the Praise of Owls. an Oration to the Conscript Fathers, and Patrons of Owls [Commentary]

Please do not remove this page Laus ululae. The praise of owls. An oration to the conscript fathers, and patrons of owls [commentary] Primer, Irwin; Goeddaeus, Conradus, -1658; Foxton, Thomas, 1697-1769 https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643419670004646?l#13643532910004646 Primer, I., Goeddaeus, C., -1658, & Foxton, T., 1697-1769. (2013). Laus ululae. The praise of owls. An oration to the conscript fathers, and patrons of owls [commentary]. Rutgers University. https://doi.org/10.7282/T3MS3QQV This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/30 14:15:57 -0400 LAUS ULULAE. The Praise of Owls. An ORATION TO THE Conscript Fathers, and Patrons of OWLS. Written in LATIN, By CURTIUS JAELE. [i.e., Conradus Goddaeus (1612-1658)] Translated By a CANARY BIRD [i.e., Thomas Foxton (1697-1769)]. Edited with an Introduction by Irwin Primer Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University 2013 INTRODUCTION to the English Translation of Laus Ululae by Irwin Primer The translation presented here, first published in 1726, has been largely unknown to anglophone readers for almost 300 years. Laus Ululae, The Praise of Owls is a loose translation of a Latin work named Laus Ululae, which, according to the OCLC database, was first published in Amsterdam in 1640 and was later reprinted a few times in the seventeenth century. Because this translation was apparently withdrawn from the market by its publisher, only a few copies have survived.