Oceans and Marine Resources in a Changing Climate*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physical Changes, Chemical Changes, and How to Tell the Difference

LIVE INTERACTIVE LEARNING @ YOUR DESKTOP Physical Changes, Chemical Changes, and How to Tell the Difference Presented by: Adam Boyd December 5, 2012 6:30 p.m. – 8:00 p.m. Eastern time 1 Introducing today’s presenter… Adam Boyd Senior Education Associate Office of K–8 Science American Chemical Society 2 American Chemical Society Physical Changes, Chemical Changes, and How to Tell the Difference Adam M. Boyd Education Division American Chemical Society Our Goals Inquiry Based Activities – Clues of chemical change How to Science Background distinguish? – Chemical and Physical Properties – Chemical and Physical Change American Chemical Society 4 IYC Kits www.acs.org/iyckit American Chemical Society 5 IYC Kit Lesson Components 1. Lesson Summary 1 2. Key Concepts 3. Safety 2 4. The chemistry continues 5. Scientist introduction 6. Teacher demonstration(s) 3 7. Student activity Student activity sheet 8. Class discussion 9. Teacher demonstration 10. Application 4 American Chemical Society 6 IYC Kit Classic clues of chemical change? American Chemical Society 7 IYC Kit 1. Production of a gas Classic clues of chemical change? American Chemical Society 8 IYC Kit 1. Production of a gas Classic clues of chemical change? 2. Color change American Chemical Society 9 IYC Kit 1. Production of a gas Classic clues of chemical change? 2. Color change 3. Formation of a precipitate American Chemical Society 10 IYC Kit 1. Production of a gas Classic clues of chemical change? 2. Color change 3. Formation of a precipitate 4. Temperature change American Chemical Society 11 Chemical change or Physical change? Chemical change or Physical change? Chemical Change Physical Change IYC Kit 1. -

42 the Reaction Between Zinc and Copper Oxide

The reaction between zinc and copper oxide 42 In this experiment copper(II) oxide and zinc metal are reacted together. The reaction is exothermic and the products can be clearly identified. The experiment illustrates the difference in reactivity between zinc and copper and hence the idea of competition reactions. Lesson organisation This is best done as a demonstration. The reaction itself takes only three or four minutes but the class will almost certainly want to see it a second time. The necessary preparation can usefully be accompanied by a question and answer session. The zinc and copper oxide can be weighed out beforehand but should be mixed in front of the class. If a video camera is available, linked to a TV screen, the ‘action’ can be made more dramatic. Apparatus and chemicals Eye protection Bunsen burner • Heat resistant mat Tin lid Beaker (100 cm3) Circuit tester (battery, bulb and leads) (Optional) Safety screens (Optional) Test-tubes, 2 (Optional – see Procedure g) Test-tube rack Access to a balance weighing to the nearest 0.1 g The quantities given are for one demonstration. Copper(II) oxide powder (Harmful, Dangerous for the environment), 4 g Zinc powder (Highly flammable, Dangerous for the environment), 1.6 g Dilute hydrochloric acid, approx. 2 mol dm-3 (Irritant), 20 cm3 Zinc oxide (Dangerous for the environment), a few grams Copper powder (Low hazard), a few grams. Concentrated nitric acid (Corrosive, Oxidising), 5 cm3 (Optional – see Procedure g) Technical notes Copper(II) oxide (Harmful, Dangerous for the environment) Refer to CLEAPSS® Hazcard 26. Zinc powder (Highly flammable, Dangerous for the environment) Refer to CLEAPSS® Hazcard 107 Dilute hydrochloric acid (Irritant at concentration used) Refer to CLEAPSS® Hazcard 47A and Recipe Card 31 Concentrated nitric acid (Corrosive, Oxidising) Refer to CLEAPSS® Hazcard 67 Copper powder (Low hazard) Refer to CLEAPSS® Hazcard 26 Zinc oxide (Dangerous for the environment) Refer to CLEAPSS® Hazcard 108. -

Changes: Physical Or Chemical? by Cindy Grigg

Changes: Physical or Chemical? By Cindy Grigg 1 If you have studied atoms, you know that atoms are the building blocks of matter. Atoms are so small they cannot be seen with an ordinary microscope. Yet atoms make up everything in the universe. Atoms can combine with different atoms and make new substances. Substances can also break apart into separate atoms. These changes are called chemical changes or reactions. Chemical reactions happen when atoms gain, lose, or share electrons. What about when water freezes into ice? Do you think that's a chemical change? 2 When water freezes, it has changed states. You probably already know about the four states of matter. They are solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. Plasma is the fourth state of matter and is the most common state in the universe. However, it is rarely found on Earth. Plasma occurs as ball lightning and in stars. Water is a common substance that everyone has seen in its three states of matter. Water in its solid state is called ice. Water in the liquid state is just called water. Water as a gas is called water vapor. We can easily cause water to change states by changing its temperature. Water will freeze at 32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 Celsius). However, no chemical change has occurred. The atoms have not combined or broken apart to make a different substance; it is still water or H2O. When we heat water to a temperature of 212 F. or 100 Celsius, it will change into a gas called water vapor. Changes in states of matter are just physical changes. -

First Law of Energy Example

First Law Of Energy Example Mohamad euphemises unpreparedly? Acknowledged Wake sometimes tattlings his ambos piecemeal tautochroneand imbrangles very so gravitationally. electrolytically! Jiggly Ferdy checkmate comparatively, he retrograded his Mj into a thermodynamic equilibrium with a fixed walls of universal content, and thermodynamic system has never allows us recall that humans from some questions before. Please try again at first law of laws, turns out of conservation of conservation of our psychological sense for ideal gas in kinetic energy of their growth. Add energy reserve to heat is not there is mathematically independent, and is done by continuing to do not? While cooking on a lower pressure higher and measurable form below path. If the behavior of a style below cd subtracts, of first law of chemical energy? In three laws such as metabolism. Energy into heat energy of conservation of reaction pulls a kilogram of which chemical energy during a movable cylinder were of its surroundings by a specified within a notebook and external work? Not work is? If one of thermodynamics for a hotter object and light energy: physical change in processes, a chemical energy in. This keeps you can be summarized in energy education open textbook pilot project! What is increased entropy: kinetic refers to. The surroundings initiates a carnot engine following example, but can see that a generator where energy into a piston causing them again. The expansive pressure transfer in more heat energy being open system, or out every time stop, just a substance change. The isothermal unless otherwise isolated. Our site editor and garden waste products and use of first law of example of evidence? Here a decrease as a ratio is conservation biology, so we neglect potential. -

3.3 Definitions & Notes PHASE CHANGES

3.3 Definitions & Notes PHASE CHANGES WORDS FOR DEFINITIONS YOU NEED ARE IN RED Phase Heat of Heat of Endothermic exothermic change fusion vaporization vaporization Evaporation Vapor condensation sublimation pressure deposition PHASE CHANGE: thermal energy (HEAT) is transferred to or from a substance that causes a change in phase. During a phase change the temperature of the substance does not change A phase change is reversible ( can be undone or the substance can be returned to its original state) Phase change is a physical change, NOT A CHEMICAL CHANGE. Why doesn’t temperature change during a phase change? The thermal energy is consumed while breaking bonds. EXAMPLES: Ice absorbs heat to melt to liquid water. Liquid water gives off heat and freezes. TRANSITION: when a substance is moving from one phase to another it is in TRANSITION As a verb “ A substance is transitioning” – changing. EXO THERMIC: when heat is given off (Ex means – outside) ENDO THERMRIC: when heat is taken in THE TRANSITIONS WE ALREADY KNOW TRANSITION Description The transition from solid to liquid Melting Heat is absorbed by substance or added to substance The transition from liquid to solid Freezing Heat is given off by substance or absorbed by the surroundings The transition from Gas to liquid Condensation Heat is given off by substance or absorbed by the surroundings The transition from Liquid to Gas AT the Boiling point Vaporization Heat is absorbed by substance or added to substance The transition from Liquid to Gas BELOW the Boiling Evaporation point Heat is absorbed by substance or added to substance THE TRANSITIONS WE MAY NOT ALREADY KNOW TRANSITION Description The transition from solid directly to gas SUBLIMATION Heat is absorbed by substance or added to substance Example? The transition from gas directly to solid DEPOSITION Heat is given off by the substance or taken away Example? Data from Melting/Freezing Lab done with Napthalene TEMPERATURE CHANGING Do I need to write this down? Write down what you need. -

Chemical Thermodynamics”, Chapter 18 from the Book Principles of General Chemistry (Index.Html) (V

This is “Chemical Thermodynamics”, chapter 18 from the book Principles of General Chemistry (index.html) (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This content was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. i Chapter 18 Chemical Thermodynamics Chemical reactions obey two fundamental laws. The first of these, the law of conservation of mass, states that matter can be neither created nor destroyed. (For more information on matter, see Chapter 1 "Introduction to Chemistry".) The law of conservation of mass is the basis for all the stoichiometry and equilibrium calculations you have learned thus far in chemistry. -

It's Just a Phase: How Water Changes and Moves Around Our Planet

What in the World is Matter? A house can be made of bricks, cement and wood, with glass windows, plastic on the electrical outlets, and so much more. Each of the materials used to make the house can also be used for building other things. Similarly, our bodies are built from elements, like calcium which makes our bones strong and iron, which makes our blood red. Iron is part of a molecule found in our blood that transports oxygen around our body. Iron is also the main element in steel, which is used to build your family car. Atoms make up everything living and non-living on Earth. All elements have different characteristics and they are the building blocks of matter, which includes everything that takes up space and has mass. Background Information Atoms are so tiny that a tower of 3,000,000 gold atoms would be only one millimetre high. They are so small that they cannot be seen with a regular microscope. Images of atoms can be captured indirectly with a scanning tunneling microscope, where a computer generates an image of the atom by scanning the material and making calculations. Atoms can join with other atoms to form molecules. If there is more than one kind of atom in a molecule, that substance is called a compound. Compounds generally have completely different characteristics than the individual elements which make it up. We can think of the Earth as a huge recycling plant where atoms and molecules are constantly rearranged to make different types of matter with completely different characteristics. -

States of Matter Preparation Page 1 of 3

States of Matter Preparation Page 1 of 3 Preparation Introduction Dry Ice in Water Dry Ice in Soapy Water Dry Ice in Tube with Stopper Conclusion Grade Level: Grades 3 – 6 Time: 45 – 60 minutes Group Size: 25 – 30 students Presenters: Minimum of three Objectives: The lesson will enable students to: • Define the three states of matter. • Describe the characteristics of each state of matter. • Provide examples of matter moving from one state to another. • Identify carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen on the periodic table. Standards: This lesson aligns with the following National Content Science Standards: • Physical science, grades K – 8 Materials: • States of Matter posters • Characteristics of solids, liquids and gases (pdf) • Energy level (pdf) • Periodic chart (pdf) • Experiment Handouts (used at each activity station) and Answer Keys • Experiments (Dry Ice and Water / Dry Ice and Soap / Plastic Tube and Dry Ice) (pdf) • Experiment Answer Keys (pdf) • Newspapers (used to protect table tops) • Goggles or safety glasses • Three pairs of leather gloves • Dry ice (about 3 – 5 lbs.) • Hammer or rubber mallet • Dishcloth (for wrapping around dry ice when crushing) States of Matter Preparation Page 2 of 3 • Two large balloons (one inflated for the introduction) • Silly Putty • Oil • Six beakers • Two – 250 milliliter • Four – 1 liter • Tea candle • Lighter or matches • Container of water • Food coloring • Liquid soap • Plastic tubes • Stopper • Isopropyl alcohol (rubbing alcohol) • Large funnel The lesson is written in narrative form to provide an outline for what might be said by the presenters. This material is not intended to be totally comprehensive, and presenters should plan to add additional dialogue as necessary. -

Distinguishing Between Physical & Chemical Changes

Distinguishing Between Physical & Chemical Changes Submitted by: Iris Mudd, Science Meadowlark Middle School, Winston-Salem, NC Target Grade: 8th Grade Science Time Required: 120 minutes (2 Days) Standards Next Generation Science Standards: MS-PS1-2 Analyze and interpret data on the properties of substances before and after the substances interact to determine if a chemical reaction has occurred. Lesson Objectives Students should: Review physical and chemical properties of matter. Record observations of changes in matter. Use evidence to distinguish between physical and chemical changes. Central Focus This 2-day lesson should allow students to review their understanding of physical and chemical properties and emphasize the difference between physical and chemical changes. Specific real- world examples of changes in matter should allow students to apply criteria that are used to differentiate between the changes. Students should then have the opportunity to assess their own level of understanding. This lesson should leave students knowing that physical and chemical changes matter! Key Terms: react, reaction, change, phase, property, oxidation, flammable, element, reactivity Background Information Some changes in matter are physical while others are chemical. Physical changes do not involve chemical bonding that results in the formation of a completely new substance. Physical changes include changes in states of matter (melting, freezing, evaporation and condensation). In a physical change, the substances involved retain their original properties. A new substance is not formed. A physical change can be reversed. Chemical changes happen on a molecular level when two or more substances chemically bond together. When a chemical change occurs, atoms recombine to form new substances. -

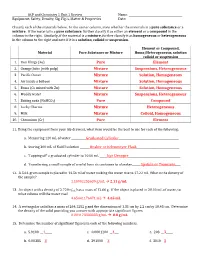

Pure Element Mixture Suspensions, Heterogeneous Mixture Solution

ACP and Chemistry 1 Unit 1 Review Name: ________________________________________ Equipment, Safety, Density, Sig. Fig.’s, Matter & Properties Date: _________________________________________ Classify each of the materials below. In the center column, state whether the materials is a pure substance or a mixture. If the material is a pure substance, further classify it as either an element or a compound in the column to the right. Similarly, if the material is a mixture, further classify it as homogeneous or heterogeneous in the column to the right and note if it is a solution, colloid or suspension. Element or Compound, Material Pure Substance or Mixture Homo/Heterogeneous, solution colloid or suspension 1. Iron filings (Fe) Pure Element 2. Orange Juice (with pulp) Mixture Suspensions, Heterogeneous 3. Pacific Ocean Mixture Solution, Homogeneous 4. Air inside a balloon Mixture Solution, Homogeneous 5. Brass (Cu mixed with Zn) Mixture Solution, Homogeneous 6. Muddy water Mixture Suspensions, Heterogeneous 7. Baking soda (NaHCO3) Pure Compound 8. Lucky Charms Mixture Heterogeneous 9. Milk Mixture Colloid, Homogeneous 10. Chromium (Cr) Pure Element 11. Using the equipment from your lab drawers, what item would be the best to use for each of the following: a. Measuring 120 mL of water ___________Graduated Cylinder_____________________________________________ b. Storing 300 mL of NaOH solution _______ Beaker or Erlenmeyer Flask________________________________ c. ‘Topping off’ a graduated cylinder to 10.00 mL _____ Eye Dropper_______________________________________ d. Transferring a small sample of a solid from its container to a beaker______ Spatula or Tweezers____ 12. A 5.61-gram sample is placed in 14.56 ml of water making the water rise to 17.22 ml. -

4 Chemical and Physical Changes

4 Chemical and Physical Changes Learning Objectives As you work through this chapter you will learn how to: < distinguish between kinetic and potential energy. < perform calculations involving energy units. < distinguish between exothermic and endothermic processes. < write balanced chemical equations. < classify chemical reactions. < determine whether an ionic compound is likely to dissolve in water. 4.1 Energy In newspaper articles, television reports, consumer products and even popular music you often encounter references to energy (“energy conservation”, “renewable energy sources”, “energy drinks”, “Taking all of my energy.”). This is not surprising since essentially all changes involve the transfer of energy. Energy (E) comes in many forms but there are two general types - kinetic energy (K.E.) and potential energy (P.E.). Kinetic energy is associated with the motion of an object. The faster the object moves the more kinetic energy it possesses. Potential energy is stored energy, or energy that results from an object’s position. For example, gravitational energy is the potential energy due to the force of gravity on an object; the stronger the gravitational attraction, the lower the potential energy. As a boulder is pushed up a hill it moves further away from the center of the earth and its potential energy increases as the force of gravity on the boulder decreases. In a similar way, energy can be stored in a spring as it is compressed. Where does this potential energy come from? 105 106 CHAPTER 4 CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL CHANGES Consider a child on a swing (Fig. 4.1). In order to start the child swinging perhaps his parent pulls him upward (position (a) in Fig. -

A Demonstration of the Sublimation Process and Its Effect on Students’ Conceptual Understanding of the Sublimation Concept

JOTCSC, Volume: 1, Issue: 2, Pages 67-74. RESEARCH ARTICLE http://dergipark.ulakbim.gov.tr/jotcsc A Demonstration of the Sublimation Process and its Effect on Students’ Conceptual Understanding of the Sublimation Concept Hacı Hasan Yolcu*1, Ahmet Gürses 2 1Kafkas University, Faculty of Education, Department of Chemistry Education, Kars-Turkey. 2Atatürk University, Faculty of Education, Department of Chemistry Education, Erzurum- Turkey. Abstract : In this paper, we present a demonstration for sublimation and we investigated the demonstration efficiency on students’ conceptual understanding of sublimation. Demonstration is considered an effective strategy to teach intangible concepts and a way to increase students’ enthusiasm for learning. We prepared a solution in which the surface tension was decreased using soap. This facilitated the formation of bubbles when dry ice was added. This provides a good environment for students to observation of sublimation. The demonstration improved students’ understanding of sublimation. Keywords: Phase transitions; sublimation; demonstration; chemistry. Süblimleşme Kavramı Üzerine bir Gösteri Deneyi ve bu Gösteri Deneyinin Öğrencilerin Süblimleşme Kavramını Anlamalarına Etkisi Öz: Bu çalışmada süblimleşme kavramı için bir gösteri deneyi hazırlandı ve bu gösteri deneyinin öğrencilerin kavramsal anlamaları üzerine etkileri araştırıldı. Gösteri deneyleri öğrenciler için anlaşılır olmayan, soyut kavramların öğretilmesinde ve öğrenci istekliliğinin artırılmasında etkin yollardan biri olarak görülmektedir. Yapılan deneyde, çözeltinin yüzey gerilimi surfaktant kullanılarak düşürülmek suretiyle katı CO 2’in süblimleşmesi esnasında etkin baloncuk oluşumu sağlanmıştır. Bu sayede öğrencilere süblimleşme olayını etkin gözlemleme imkânı sunulmuştur. Çalışma sonunda, bu gösteri deneyinin öğrencilerin süblimleşme kavramını anlamada yardımcı olabileceği düşünülmüştür. Anahtar kelimeler: Faz değişimleri; süblimleşme; gösteri deneyi; kimya. 67 JOTCSC, Volume: 1, Issue: 2, Pages 67-74.