The Night of No Moon June 4, 2009 in Uncategorized by the China Beat | No Comments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

56 Stories Desire for Freedom and the Uncommon Courage with Which They Tried to Attain It in 56 Stories 1956

For those who bore witness to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, it had a significant and lasting influence on their lives. The stories in this book tell of their universal 56 Stories desire for freedom and the uncommon courage with which they tried to attain it in 56 Stories 1956. Fifty years after the Revolution, the Hungar- ian American Coalition and Lauer Learning 56 Stories collected these inspiring memoirs from 1956 participants through the Freedom- Fighter56.com oral history website. The eyewitness accounts of this amazing mod- Edith K. Lauer ern-day David vs. Goliath struggle provide Edith Lauer serves as Chair Emerita of the Hun- a special Hungarian-American perspective garian American Coalition, the organization she and pass on the very spirit of the Revolu- helped found in 1991. She led the Coalition’s “56 Stories” is a fascinating collection of testimonies of heroism, efforts to promote NATO expansion, and has incredible courage and sacrifice made by Hungarians who later tion of 1956 to future generations. been a strong advocate for maintaining Hun- became Americans. On the 50th anniversary we must remem- “56 Stories” contains 56 personal testimo- garian education and culture as well as the hu- ber the historical significance of the 1956 Revolution that ex- nials from ’56-ers, nine stories from rela- man rights of 2.5 million Hungarians who live posed the brutality and inhumanity of the Soviets, and led, in due tives of ’56-ers, and a collection of archival in historic national communities in countries course, to freedom for Hungary and an untold number of others. -

Forensic Analysis of Gasoline in Molotov Cocktail Using Gas Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry and Chemometric Procedures

FORENSIC ANALYSIS OF GASOLINE IN MOLOTOV COCKTAIL USING GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY – MASS SPECTROMETRY AND CHEMOMETRIC PROCEDURES by MOHAMAD ISMAIL BIN JAMALUDDIN Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science October 2014 DECLARATION I declare that the material presented in this thesis is all my own work. The thesis has not been previously submitted for any other degree. Date: 27 October 2014 MOHAMAD ISMAIL BIN JAMALUDDIN P-SKM0008/12(R) 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious and the Most Merciful. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Ahmad Fahmi Lim Abdullah for giving me the opportunity to conduct this very interesting and at the same time very challenging research topic. I would also like to thank him for his fruitful guidance, knowledge and advices during my two years at the Forensic Science Programme, School of Health Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia in Kubang Kerian. Without his non-stop, continuous motivational support, I am very much sure, this thesis will not be completed let alone a successful ones. I would also like to convey my gratitude to my second supervisor, Dr. Dzulkiflee Ismail for „lending his ears‟, for his helps on the statistical software and spending his time with me throwing the Molotov Cocktails. Thanks also go to Dr. Wan Nur Syuhaila Mat Desa and Dr. Noor Zuhartini Md Muslim for her invaluable advices and support. I would also like to acknowledge the Royal Malaysian Police (RMP) for the scholarship awarded and countless assistance given to me throughout my two years of postgraduate study. -

From the Tito-Stalin Split to Yugoslavia's Finnish Connection: Neutralism Before Non-Alignment, 1948-1958

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FROM THE TITO-STALIN SPLIT TO YUGOSLAVIA'S FINNISH CONNECTION: NEUTRALISM BEFORE NON-ALIGNMENT, 1948-1958. Rinna Elina Kullaa, Doctor of Philosophy 2008 Directed By: Professor John R. Lampe Department of History After the Second World War the European continent stood divided between two clearly defined and competing systems of government, economic and social progress. Historians have repeatedly analyzed the formation of the Soviet bloc in the east, the subsequent superpower confrontation, and the resulting rise of Euro-Atlantic interconnection in the west. This dissertation provides a new view of how two borderlands steered clear of absorption into the Soviet bloc. It addresses the foreign relations of Yugoslavia and Finland with the Soviet Union and with each other between 1948 and 1958. Narrated here are their separate yet comparable and, to some extent, coordinated contests with the Soviet Union. Ending the presumed partnership with the Soviet Union, the Tito-Stalin split of 1948 launched Yugoslavia on a search for an alternative foreign policy, one that previously began before the split and helped to provoke it. After the split that search turned to avoiding violent conflict with the Soviet Union while creating alternative international partnerships to help the Communist state to survive in difficult postwar conditions. Finnish-Soviet relations between 1944 and 1948 showed the Yugoslav Foreign Ministry that in order to avoid invasion, it would have to demonstrate a commitment to minimizing security risks to the Soviet Union along its European political border and to not interfering in the Soviet domination of domestic politics elsewhere in Eastern Europe. -

Grenades and Land Mines, Japanese Robert J

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Faculty Publications and Research CGU Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2001 Grenades and Land Mines, Japanese Robert J. Bunker Claremont Graduate University Recommended Citation Bunker, Robert J. "Grenades and Land Mines, Japanese." World War II in the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing, 2001. 210-211. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Faculty Publications and Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 210 Grenades and Land Mines, Japanese nese factories This conference presented a belated justification for the were idle or only partly productive and that Pacific war. Part of the Joint Declaration of the Greater new military pilots could receive only the most rudimen East Asia Conference read: tary tram mg. In the end, the sphere did nor serve the purpose either The United States of America and the British Em of uniting East Asia against rhe Allies or of harnessing the pire have in seeking their own prosperity oppressed region's economy to the Japanese war effort. By the end other nations and peoples. Especially in East Asia, of the war, the economy of East Asia was devastated not they indulged in insatiable aggression and exploi only from war damage and the dislocation of markets but tation, and so ught to satisfy their inordinate am also from the effects of Japanese oversight, which was fo bition of enslaving the entire region, and finally cused solely on the war effort. -

Campaign Notes

The Winter War The Soviet Union’s Invasion of Finland (1939-40) The Second World War was a vast conflict with hard-fought clashes in places such as Stalingrad, Normandy, North Africa, Italy and the Pacific Theater. These operations are discussed in a hundreds of books and can be found on an infinite number of websites. Their names conjure up noble images of heroism and the sacrifice as well as the more sobering imagery of destruction and death. For 105 days, the tiny nation of Finland fought a war that typically merits only a footnote in a history book, or a passing remark in a WWII documentary. Taking on the vast manpower of the Soviet army, the Finns put up a fanatical defense of their homeland, inflicting horrific casualties on the invading Soviet army. Eventually the overwhelming number of Soviet troops and tanks sent into Finland forced the Finns to sue for peace, but they walked away from the conflict with their much bigger neighbor with their independence and national pride intact. Their struggle influenced the landscape and direction of the entire world war that followed, and perhaps the outcome as well. The winds of war were beginning to drift across the world during 1930’s. Japan sought to secure territory to increase its sources of raw materials and expand its empire. Hitler’s power and ambitious plans were ever growing storm clouds on the European horizon, threatening to overtake the entire continent and dragging a very reluctant America into the fray. The Russian Bear in the East also sought to exert its influence, all the while casting a wary eye towards Hitler’s Germany and the conflict Stalin knew would eventually come to pass between them. -

¡Espana! for Chain of Command Results in Command, a Free Supplement Which a Game Which Is Fun and Challenging in Serves As a Guide to and Lists for the Equal Measures

Welcome to ¡Espana! for Chain of ¡Espana! for Chain of Command results in Command, a free supplement which a game which is fun and challenging in serves as a guide to and lists for the equal measures. Spanish Civil War. The lists herein were compiled by Jim Hale and Rolf Grein and As previously, my thanks must go to Jim posted individually on Lard Island News in and Rolf for their tireless efforts in a quest conjunction with an extensive piece in the to find the right data through tough 2013 Christmas Special. Over the research. Their hard work means that the intervening months they have continued rest of us can get on with having fun with to work on the rule amendments in order the rules they have provided. to fine‐tune the system to reflect the Spanish Civil War. So, whether you’re facing the sun and shouting ¡Arriba Espana! or manning the We are now at a point where combining barricades with a cry of ¡No Parsaran!, all of the lists into one document seems you can do so with ¡Espana! for Chain of the right thing to do in order to provide Command. the gamer with easy access to the period. This document is the net result. Richard Clarke June 2014 Here we have all of the lists for the conflict which tore Spain apart between the years of 1936 and 1939 and still leaves its legacy with Spain today. The rules and army lists remain close to the original principles within Chain of Command, relying on reflecting the way in which the troops were organised and trained to fight. -

On War and the Winter War Robert Karnisky

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 On War and the Winter War Robert Karnisky Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ON WAR AND THE WINTER WAR by Robert Karnisky A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Robert B. Karnisky defended on June 29, 2007. ________________________ Jonathan Grant Professor Directing Thesis ________________________ Michael Creswell Committee Member ________________________ James P. Jones Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to express my gratitude to the members of my committee. These include my graduate professor, Dr. Jonathan Grant, for his advice during the writing of this work, his entertaining lectures, and especially for his patience; Dr. Michael Creswell, for introducing me to military affairs and for encouraging me to pursue this topic; and Dr. James P. Jones, for his continued interest in my academic progress, and for his fifty years of teaching at Florida State. The remaining members of the faculty and staff at FSU deserve recognition for too many reasons to be recounted here – but most of all for making my experience here so enjoyable. Rarely does someone in my circumstance receive the opportunity I have been given, and I will never forget the people who made it such a positive one. -

Anarchists Cookbook V2000

ANARCHY COOKBOOK VERSION 2000 Table of Contents 1.Counterfeiting Money 58.Generic Bomb 2.Credit Card Fraud 59.Green Box Plans 3.Making Plastic Explosives 60.Portable Grenade Launcher 4.Picking Master Locks 61.Basic Hacking Tutorial I 5.The Arts of Lockpicking I 62.Basic Hacking Tutorial II 6.The Arts of Lockpicking II 63.Hacking DEC's 7.Solidox Bombs 64.Harmless Bombs 8.High Tech Revenge: The Beigebox 65.Breaking into Houses 9.COý Bombs 66.Hypnotism 10.Thermite II Bombs 67.Remote Informer Issue #1 11.Touch Explosives 68.Jackpotting ATM Machines 12.Letter Bombs 69.Jug Bomb 13.Paint Bombs 70.Fun at K-Mart 14.Ways to send a car to HELL 71.Mace Substitute 15.Do you hate school? 72.How to Grow Marijuana 16.Phone related vandalism 73.Match Head Bomb 17.Highway police radar jamming 74.Terrorizing McDonalds 18.Smoke Bombs 75."Mentor's" Last Words 19.Mail Box Bombs 76.The Myth of the 2600hz Detector 20.Hot-wiring cars 77.Blue Box Plans 21.Napalm 78.Napalm II 22.Fertilizer Bomb 79.Nitroglycerin Recipe 23.Tennis Ball Bomb 80.Operation: Fuckup 24.Diskette Bombs 81.Stealing Calls from Payphones 25.Unlisted Phone Numbers 82.Pool Fun 26.Fuses 83.Free Postage 27.How to make Potassium Nitrate 84.Unstable Explosives 28.Exploding Light bulbs 85.Weird Drugs 29.Under water igniters 86.The Art of Carding 30.Home-brew blast cannon 87.Recognizing Credit Cards 31.Chemical Equivalency List 88.How to Get a New Identity 32.Phone Taps 89.Remote Informer Issue #2 33.Landmines 90.Remote Informer Issue #3 34.A different Molitov Cocktail 91.Remote Informer Issue #4 35.Phone -

Explosive Information

EXPLOSIVES = COMPLETE TUTORIAL Compiled by Red Dragon CHEMICAL SUBSTITUTION CHART Peroxide Lead acetate sugar of lead Lead tetroxide red lead Magnesium silicate talc Magnesium sulfate Epsom salts Naphthalene mothballs Phenol carbolic acid Potassium bitartrate cream of tartar Potassium chromium sulfate chrome alum Potassium nitrate saltpeter Silicon dioxide sand Sodium bicarbonate baking soda Sodium borate borax Sodium carbonate washing soda Sodium chloride salt Sodium hydroxide lye Sodium silicate water glass Sodium sulfate Glauber's salt Sodium thiosulfate photographer's hypo BOTTLE GRENADE This one's really simple, but a lot of people forget about these kinds Of simple weapons. Anyway, get yourself a glass bottle, some vinegar and Baking soda, (Any substances that react in an expulsion of gas will work) and a good strong SCREW-ON cap. When you want to fire it, you put the Vinegar and baking soda in the bottle, (The amounts depend on the size of the bottle...) and toss it. It works, but it's mainly an antipersonnel weapon, and if the bottle breaks you're screwed... TENNIS BALL CANNON Get 4 or 5 seven-up cans, cut the tops off of 3 or 4 respectively, and put holes (SMALL ONES, please...) in the top of the last can, drill a hole the diameter of an Ohio Blue Tip match in the side of the can, about 1&122 inches from the bottom of the can. Then stick a tennis ball in the top of the cannon, squirt in some lighter fluid in the little hole, and hold a flame under the hole. If you've done it right, it'll work. -

(U) Counterterrorism (U//FOUO) Violent Opportunist Tactics

UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY 1 June 2020 (U) Counterterrorism (U//FOUO) Violent Opportunist Tactics Observed During Civil Disturbances 26-31 May (U//FOUO) Scope. This Intelligence Note (IN) provides a summary of tactics used by violent opportunists observed in conjunction with lawful protests since 26 May 2020. While this IN focuses on the current period of opportunistic violence during lawful nationwide protests, many of the tactics discussed here have previously been encountered by security officials and are likely to be encountered during future disruption of lawful protest activity by violent opportunists. This information is being provided to federal, state, and local partners to aid in awareness of violent opportunists’ and domestic violent extremists’ (DVEs) tactics and to aid in mitigation panning for future events where these tactics may be encountered. This IN is current as of 31 May 2020. (U//FOUO) Prepared by the DHS Intelligence Enterprise (DHS IE) Counterterrorism Mission Center (CTMC). Coordinated with CBP, CISA, CWMD, DHS IE Field Operations Division, ICE, JCAT, NCTC, TSA, and USCG. (U//FOUO) We assess that violent opportunists will continue to exploit ongoing nationwide lawful protests as a pretext to attempt to disrupt law enforcement operations; target law enforcement personnel, assets, and facilities; and damage public and private property. We have identified multiple tactics currently at play, including the use of weapons, counter-mobility, physical barriers, screening and concealment, intercepted communications, and pre-operational activities. (U//FOUO) Weapons Tactics (U//FOUO) Improvised Incendiary Devices (IIDs): We have received numerous reports of violent opportunists using Molotov Cocktails targeting law enforcement assets. A Molotov Cocktail is a generic term for any handheld, flammable liquid-based, improvised incendiary device contained in a bottle. -

Weapons Table the Game System

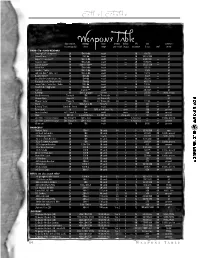

Call of Cthulhu base chance, damage base attacks bullets HPs era common or starting skill done range per round in gun resistance $ cost mal in era HAND—TO—HAND WEAPONS Fencing Foil*, sharpened 20 1D6+1+db touch 1 — 10 4/6/70 — all Sword Cane* 20Weapons 1D6+db touch Table 1 — 10 10/25/100 — all Rapier / Heavy Epee* 10 1D6+1+db touch 1 — 15 6/20/150 — all Cavalier Sabre 15 1D8+1+db touch 1 — 20 15/30/75 — all Cavalry Lance* 10 1D8+1+1D6** touch 1 — 15 15/25/150 — all Wood Axe 20 1D8+2+db touch 1 — 15 3/5/10 — all Hatchet / Sickle 20 1D6+1+db touch 1 — 12 2/3/9 — all Fighting Knife* (dirk, etc.) 25 1D4+2+db touch 1 — 15 1/2/15 — all Butcher Knife* 25 1D6+db touch 1 — 12 1/2/7 — all Small Knife* (switchblade, etc.) 25 1D4+db touch 1 — 9 .50/2/6 — all Blackjack (cosh, life-preserver) 40 1D8+db touch 1 — 4 .60/2/15 — all Large Club / Cricket Bat / Poker 25 1D8+db touch 1 — 20 1/3/35 — all Small Club / Nightstick 25 1D6+db touch 1 — 15 1/3/35 — all Garrote 15 strangle*** touch 1 — 1 .20/.50/3 — all Bullwhip 05 1D3 or grapple 10 feet 1 — 4 2/5/50 — 1890s, 1920s War Boomerang Throw % 1D8 see Throw rule 1/2 — 8 1/2/40 — rare Thrown Rock Throw % 1D4 see Throw rule 1 — — — — all Thrown Spear Throw % 1D8+1 see Throw rule 1/2 — 15 1/1/25 — rare Quoit 25 1D6+1+1/2 db Throw% 1 — 15 .05 — all Burning Torch 10+cloth. -

5131.7 Passaic, New Jersey X Monitored X Mandated Regulation X Other Reasons

PASSAIC PUBLIC SCHOOLS FILE CODE: 5131.7 Passaic, New Jersey X Monitored X Mandated Regulation X Other Reasons WEAPONS AND DANGEROUS INSTRUMENTS A. Definitions: 1. "Weapon" includes: a. Firearms, which include any handgun, rifle, shotgun, machine gun, automatic or semiautomatic rifle, or any gun, device, or instrument in the nature of a weapon from which may be fired or ejected any solid projectable ball, slug, pellet, missile, or bullet, or any gas, vapor or other noxious thing, by means of a cartridge or shell or by the action of an explosive or the igniting of flammable or explosive substances. It also includes any firearm that is in the nature of an air gun, spring gun or pistol, or other weapon of a similar nature in which the propelling force is a spring, elastic band, carbon dioxide, compressed or other gas or vapor, air or compressed air, or is ignited by compressed air, and ejecting a bullet or missile smaller than three-eighths of an inch in diameter, with sufficient force to injure a person. b. Components that can be readily assembled into a weapon. c. Gravity knives, which means any knife that has a blade that is released from the handle or sheath thereof by the force of gravity or the application of centrifugal force. d. Switchblade knives, which means any knife or similar device that has a blade that opens automatically by hand pressure applied to a button, spring, or other device in the handle of the knife. e. Daggers, dirks, stilettos, and other dangerous knives. f. Ballistic knives, which mean any device capable of lethal use that, can propel a knife blade.