A Scoping Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safap October2016 Minutes Final

Minutes of the meeting of THE SCOTTISH ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS ALLOCATION PANEL 10:45am, Thursday 27th October 2016 Present: Dr Evelyn Silber (Chair), Neil Curtis, Dr Murray Cook (via Skype), Jilly Burns (NMS), Paul MacDonald, Richard Welander (HES), Mary McLeod Rivett In attendance: Stuart Campbell (TTU), Dr Natasha Ferguson (TTU), Andrew Brown (QLTR Solicitor). Dr Natasha Ferguson took the minutes 1. Apologies Apologies from Jacob O’Sullivan (MGS). 2. Chair Remarks The Chair informed the panel that the QLTR had received a response from SG to a letter highlighting issues relating to increasing numbers of disclaimed cases. It was agreed the points would be discussed further at the Annual Review Meeting on 14th November. The panel agreed to form a sub-committee (of NC, JB, RW & AB) to deal with revisions of the Code of Practice in relation to multiple applications. The next date of the panel meeting confirmed as Thursday 23rd March 2017. Further dates in 2017 to be proposed. It is proposed that the number of meetings is reduced to three by combining the Annual Review meeting with a panel meeting. This will be discussed at the next Annual Review meeting on 14th November 2016. 3. Discussion of Galloway Hoard, valuations and timescales JB (NMS) was absent from this discussion. The panel were updated on the current status of the Galloway Hoard, including projected timescales for allocation. The panel also discussed the criteria for assessing the valuations. The 31st January 2017 was agreed as a proposed date to hold an extraordinary SAFAP meeting in relation to allocating the Galloway Hoard. -

Lochview Loch Achilty, Strathpeffer, Ross-Shire

Lochview Loch Achilty, Strathpeffer, Ross-shire Lochview Loch Achilty, Strathpeffer, Ross-shire, IV14 9EN A beautifully positioned detached home enjoying a spectacular location on the bank of Loch Achilty Contin 3 miles, Strathpeffer 4 miles, Dingwall 8 miles, Inverness 20 miles, Inverness Airport 26 miles Ground Floor Entrance hallway | Open plan lounge Dining area | Sun room | Dining kitchen Utility room | WC/cloak | En suite bedroom Rear hall | Bar/dining room/bedroom Upper Floor: Upper gallery | Master bedroom with en suite 2 Further en suite double bedrooms The Property Lochview is an aptly named spacious detached of the house has been designed to maximise reception hall is an en suite bedroom and The detached garage has a workshop area home sitting proudly in an elevated position both the views over the Loch and countryside large reception room, currently utilised as with power and lighting. A staircase to the overlooking Loch Achilty. The property as well as attract an abundance of natural light. ‘Fishermans Bar’. This room has a wonderful side leads to an area above the garage which has been comprehensively upgraded and Features include hardwood flooring, feature open fireplace and has been equipped with provides excellent storage facilities and further provides substantial living space over fire place with inset open fire and sliding patio a bar, table and chairs and provides an development potential subject the appropriate two levels with an impressive layout and doors from the sun room leading directly to ideal room to entertain friends. The layout permissions. To the rear of the garage there specification. The property blends in nicely the landscaped gardens. -

IN Tune with NATURE No Crop Marks

Nàdar air ghleus – farpais sgrìobhaidh airson ceòl is òrain Inviting musicians of all genres to compose new music as part of a high-profile national composition and song writing project called In Tune with Nature. What is the competition? To celebrate Scotland’s Year of Coasts and Waters, artists aged 16+ are invited to write new music inspired by one of ten National Nature Reserves (NNRs) across the country. What do I win? The entries will be judged by a panel of well-known and highly regarded musicians and industry professionals, including Julie Fowlis, Vic Galloway, Gill Maxwell and Karine Polwart, and chaired by Fiona Dalgetty. The 10 winning artists will each win a £500 cash prize as well as the opportunity to make a film on the NNR site which inspired their music. The winning artists will be paid for their time on site making the film. There will also be the opportunity to take part in live performances throughout the year. The NNRs include: Beinn Eighe (Ross-Shire), Caerlaverock (Dumfries), Creag Meagaidh (Lochaber), Forvie (North East), Isle of May (Firth of Forth), Loch Leven (Perthshire), Noss (Shetland Islands), Rum (Inner Hebrides), Tentsmuir (Fife) and Taynish (Argyll). To find out more visit nature.scot The new work should reflect the special qualities of the National Nature Reserves, all those selected having strong coastal or freshwater elements. New Gaelic songs are particularly encouraged in the Beinn Eighe and Creag Meagaidh areas and, similarly, songs written in Scots and regional dialects would be warmly received in other areas. Artists should aim to communicate the richness of Scotland’s nature and, through this, encourage new audiences to consider the actions they may take to protect it. -

Camping Pocket Guide

CONTENTS Get Ready for Camping 04 Add To Your Experience 07 Enjoy Family Picnics 08 Scenic Scotland 10 Visit National Parks 14 Amazing Wildlife 16 GET READY FOR CAMPING - Stargazing - Experience the freedom of a touring trip, where you can Sleeping under the stars is the perfect opportunity to wake up in a different part of the country every day. Or get familiar with the wonders of the sky at night. Plan enjoy a bit of luxury at a holiday park and spend a restful a camping trip to the Glentrool Camping and Caravan week in the comfy surrounds of a state-of-the-art static Site in the Galloway Forest Park, the UK’s first Dark Sky caravan, or pack in some fun activities with the kids. Park, or sail to Scotland’s first Dark Sky island. There’s There’s a camping and caravanning holiday in Scotland minimum light pollution on the Isle of Coll, where the to suit every preference and budget. nearest lamppost is 20 miles away! Start planning a break today and find your perfect Experience more stargazing opportunities and discover camping or caravanning destination. Scotland’s inky black skies on our website. - Stunning views - - Campsites near castles - Summer is the time to be spontaneous – pack the tent Why not combine your camping or caravanning trip into the car, head out onto the open road, and pitch up in with a bit of history and book a pitch in the grounds of a some beautiful locations. You’ll find campsites set below castle? You’ll find such camping grounds in many parts breathtaking mountain ranges, overlooking pristine of the country, from the impressive 18th century Culzean beaches, or in the middle of lush, open countryside. -

Archaeological Excavations at Castle Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, (1996)6 12 , 517-557 Archaeological excavation t Castlsa e Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90 Gordon Ewart Triscottn Jo *& t with contributions by N M McQ Holmes, D Caldwell, H Stewart, F McCormick, T Holden & C Mills ABSTRACT Excavations Castleat Sween, Argyllin Bute,& have thrown castle of the history use lightthe on and from construction,s it presente 7200c th o t , day. forge A kilnsd evidencee an ar of industrial activity prior 1650.to Evidence rangesfor of buildings within courtyardthe amplifies previous descriptions castle. ofthe excavations The were funded Historicby Scotland (formerly SDD-HBM) alsowho supplied granta towards publicationthe costs. INTRODUCTION Castle Sween, a ruin in the care of Historic Scotland, stands on a low hill overlooking an inlet, Loch Sween, on the west side of Knapdale (NGR: NR 712 788, illus 1-3). Its history and architectural development have recently been reviewed thoroughl RCAHMe th y b y S (1992, 245-59) castle Th . e s theri e demonstrate havo dt e five major building phases datin c 1200 o earle gt th , y 13th century, c 1300 15te th ,h century 16th-17te th d an , h centur core y (illueTh . wor 120c 3) s f ko 0 consista f so small quadrilateral enclosure castle. A rectangular wing was added to its west face in the early 13th century. This win s rebuilgwa t abou t circulaa 1300 d an , r tower with latrinee grounth n o sd floor north-ease th o buils t n wa o t t enclosurcornee th 15te f o rth hn i ecentury l thesAl . -

Strathpeffer Spa: Dr William Bruce and Polymyalgia Rheumatica

Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.40.5.503 on 1 October 1981. Downloaded from Annals of the Rheumatic Disease, 1981, 40, 503-506 Strathpeffer Spa: Dr William Bruce and polymyalgia rheumatica ALASTAIR G. MOWAT From the Department ofRheumatology, Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, Oxford SUMMARY The first description of polymyalgia rheumatica is attributed to Dr William Bruce working in Strathpeffer Spa, Scotland, in 1888. His career, the history of the spa, and the original article are briefly described. 'Near here is a valley, birchwoods, heather and a stream- succeeded in finding alleviation for his arthritis at No country, no place was ever for a moment so delightful to Strathpeffer when he had failed at other British spas, my soul." decided to retire in the valley and devote his energies A Scottish spa may seem a contradiction in terms, to extending the spa's benefits to a wider public. One but Strathpeffer, 24 miles north-west of Inverness result was the first, wooden pump room in 1819. Its and protected in its wooded valley from the prevailing remoteness as the only true spa north of Harrogate winds by 3500 ft (1070 m) Ben Wyvis is 'set like a hindered its development, and Fox2 wrote, 'old men jewel' mid the splendors of the North.'2 still alive remember the month's journey from copyright. The first medical reference to the springs is in a London with the Laird's coach'. However, the paper by Dr Donald Munro to the Royal Society in Highland Railway pushing steadily northward 1772,3 and 5 years later the Rev. -

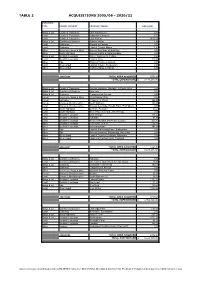

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

Castle Leod Strathpeffer, Easter Ross Archaeological Test Pitting Evaluation

Ross and Cromarty Archaeological Services West Coast Archaeological Services Castle Leod Strathpeffer, Easter Ross Archaeological Test Pitting Evaluation Ross and Cromarty Archaeological Services West Coast Archaeological Services Ryefield, Tore, Ross-shire, IV6 7SB The Salmon Bothy, Shore St, Cromarty, IV11 8XL Tel: 01463 811310 Tel: 01381 600726 Mobile: 07776 027306 Mobile: 07867 651886 [email protected] [email protected] www.rossandcromarch.co.uk Castle Leod Archaeological Evaluation Strathpeffer, Easter Ross Results of the Archaeological Test Pitting Evaluation National Grid NH 4860 5933 Reference NMRS No. NH45NE 9 Protected Status Listed Building (A) 7826: Castle Leod Highland HER No. MHG6283 RoCAS Report 2014-35/CLD14 OASIS No. rosscrom1-196922 Date 28 November 2014 Author Mary Peteranna 1 Castle Leod, Strathpeffer: Results of an archaeological evaluation in May 2014 CONTENTS 1.0 Summary 4 2.0 Introduction 4 3.0 Archaeological and historical background 7 4.0 Aims and objectives 9 5.0 Fieldwork methodology 9 6.0 Results 11 7.0 Conclusions and recommendations 17 8.0 References 18 Appendices Appendix 1 List of Photographs 19 Appendix 2 List of Small Finds 21 Appendix 3 List of Drawings 13 Appendix 4 List of Contexts 24 Appendix 5 Notes on the glass from Castle Leod 27 K. Robin Murdoch List of Figures Figure 1 Landscape location of Castle Leod Figure 2 Trench locations Figure 3 E-facing section of Trench 2, showing the possible wall (2.08) and ditch (2.10) Figure 4 SW wall of Castle Leod showing the foundations (Context 4.11) -

Pib: a Memoir of Colin Pibworth

FRANK CARD Pib: A Memoir of Colin Pibworth ike any other organisation, a mountain rescue team needs not only its Lcourageous innovators, like FIt Lt Des Graham', but equally those who, over the years, provide the structure with a focus and continuity. Whilst they do not necessarily achieve the commanding heights, their contribution is very often just as valuable. One such was Colin Pibworth ('Pib'), who died in 2001 after an extraordinarily long career in the RAF Mountain Rescue Service. In those thirty years he never got beyond the rank of corporal, though for several periods, as a team leader, he was made up to sergeant. But his influence was enormous. During my researches2 in 1992,JllY wife Jo and I visited the Mountain Rescue Team at RAF Valley. 'You must go and see Pib,' said one of the lads. By this time, I had certainly heard of Colin Pibworth, but had no idea where he could be found. But some of the team knew him, and visited him from time to time. We were directed from RAF Valley into the hills behind Caernarfon and up a steep narrow lane. Eventually we came to a tiny cottage, its roof bristling with CB aerials. A smiling man in his 60s met us at the door, cradling in his arms a cat called Tenzing. 'Why Tenzing?' I asked at some stage. 'Because he's a bit of a cloimber,' came the reply. Ask a silly question. There followed an enthralling hour or so ofstories ranging from blizzards and avalanches in the Highlands to Desert Rescue operations with the Sharjah and Masirah Mountain and Desert Rescue Teams (MDRTs). -

Llywodraeth Cymru / Welsh Government A487 New Dyfi Bridge Environmental Statement - Volume 3: Appendix 9.1

Llywodraeth Cymru / Welsh Government A487 New Dyfi Bridge Environmental Statement - Volume 3: Appendix 9.1 Desk Study and Extended Phase 1 Report Final Issue | September 2017 Llywodraeth Cymru/Welsh Government A487 New Dyfi Bridge Desk Study and Extended Phase 1 Report Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Scope of this Report 1 2 Methodology 2 2.1 Desk Study 2 2.2 Extended Phase 1 Habitat Survey 2 2.3 Hedgerow Assessments 3 2.4 Limitations 6 3 Baseline Conditions 7 3.1 Desk Study 7 3.2 Extended Phase 1 Habitat Survey 15 3.3 Hedgerow Assessments 19 3.4 Potential for Protected Species 20 4 Conclusion 24 References Figures Figure 1 Site Location Plan Figure 2 Statutory Designated Sites Figure 3 Non-Statutory Designated Sites Figure 4 Phase 1 Habitat Plan (01) Figure 5 Phase 1 Habitat Plan (02) Figure 6 Hedgerow Assessment Appendices Appendix A Legislative Context Appendix B Extended Phase 1 Target Notes 900237-ARP-ZZ-ZZ-RP-YE-00030 | P01.1 | 15 July 2016 C:\PROJECTWISE\ARUP UK\PETE.WELLS\D0100636\900237-ARP-ZZ-ZZ-RP-YE-00030.DOCX Llywodraeth Cymru/Welsh Government A487 New Dyfi Bridge Desk Study and Extended Phase 1 Report Appendix C Hedgerows Assessed for Importance 900237-ARP-ZZ-ZZ-RP-YE-00030 | P01.1 | 15 July 2016 C:\PROJECTWISE\ARUP UK\PETE.WELLS\D0100636\900237-ARP-ZZ-ZZ-RP-YE-00030.DOCX Llywodraeth Cymru/Welsh Government A487 New Dyfi Bridge Desk Study and Extended Phase 1 Report 1 Introduction 1.1 Background Ove Arup and Partners Ltd was commissioned by Alun Griffiths (Contractors) Ltd to undertake ecological surveys to inform an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of the proposed A487 New Dyfi Bridge scheme (The Scheme) on land to the north of Machynlleth, Mid-Wales, located at National Grid Reference SH747017. -

History of the Lands and Their Owners in Galloway

H.E NTIL , 4 Pfiffifinfi:-fit,mnuuugm‘é’r§ms, ».IVI\ ‘!{5_&mM;PAmnsox, _ V‘ V itbmnvncn. if,‘4ff V, f fixmmum ‘xnmonasfimwini cAa'1'm-no17t§1[.As'. xmgompnxenm. ,7’°':",*"-‘V"'{";‘.' ‘9“"3iLfA31Dan1r,_§v , qyuwgm." “,‘,« . ERRATA. Page 1, seventeenth line. For “jzim—g1'é.r,”read "j2'1r11—gr:ir." 16. Skaar, “had sasiik of the lands of Barskeoch, Skar,” has been twice erroneously printed. 19. Clouden, etc., page 4. For “ land of,” read “lands of.” 24. ,, For “ Lochenket," read “ Lochenkit.” 29.,9 For “ bo,” read “ b6." 48, seventh line. For “fill gici de gord1‘u1,”read“fill Riei de gordfin.” ,, nineteenth line. For “ Sr,” read “ Sr." 51 I ) 9 5’ For “fosse,” read “ fossé.” 63, sixteenth line. For “ your Lords,” read “ your Lord’s.” 143, first line. For “ godly,” etc., read “ Godly,” etc. 147, third line. For “ George Granville, Leveson Gower," read without the comma.after Granville. 150, ninth line. For “ Manor,” read “ Mona.” 155,fourth line at foot. For “ John Crak,” read “John Crai ." 157, twenty—seventhline. For “Ar-byll,” read “ Ar by1led.” 164, first line. For “ Galloway,” read “ Galtway.” ,, second line. For “ Galtway," read “ Galloway." 165, tenth line. For “ King Alpine," read “ King Alpin." ,, seventeenth line. For “ fosse,” read “ fossé.” 178, eleventh line. For “ Berwick,” read “ Berwickshire.” 200, tenth line. For “ Murmor,” read “ murinor.” 222, fifth line from foot. For “Alfred-Peter,” etc., read “Alfred Peter." 223 .Ba.rclosh Tower. The engraver has introduced two figures Of his own imagination, and not in our sketch. 230, fifth line from foot. For “ his douchter, four,” read “ his douchter four.” 248, tenth line. -

2. Remembering Strathpeffer.Pdf

Remembering the Strathpeffer Area: 2. Strathpeffer Photo © Margaret Spark Photo ©Margaret Spark During 2015 people gathered at Strathpeffer Community Centre and Achterneed Hall to remember the physical remains of the Strathpeffer area – Jamestown, Strathpeffer, the Heights, Achterneed and Milnain – focussing on buildings, sites, or monuments which were new, modified or no longer there. They built on previous sessions which had begun to look at Strathpeffer. Using old maps, photographs (some more than a century old), various printed sources, and memories spanning over 80 years, information about over 350 sites was gathered. Some pupils from the school joined us as well for Strathpeffer sessionsas part of their project investigating World War II. This report summarises the results of the meetings focussing on Strathpeffer, including Kinellan. The details have also been forwarded to heritage databases: the Highland Council Historic Environment Record (HER) (her.highland.gov.uk) and Historic Environment Scotland’s Canmore (canmore.org.uk) where they will provide valuable new information about the heritage of the area. The 2015 sessions were part of a project organised by ARCH and Strathpeffer Community Centre, and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Mackenzie New York Villa Trust. Funding for the smaller projects in previous years was provided by Generations Working Together and High Life Highland. Thanks also to the Highland Museum of Childhood for allowing us to see text panels from their 2009 ‘Hands Across the Sea’ exhibition. But most of all thanks to everyone who has shared their memories and photographs, often braving difficult weather. Any additions or corrections should be sent to ARCH at [email protected] or The Goods Shed, The Old Station, Strathpeffer, IV14 9DH.