Strengthening Libraries at Historically Black Colleges and Universities Project Planning Grant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HBCU Brochure.Qxp

HBCU Library Alliance 2010 Membership Meeting Looking Back, Moving Forward HBCU Libraries Using Digital Technologies to Reach, Teach, and Connect Faculty Group in 1937 Commencement at Alabama State University, image from the HBCU Digital Collection October 23-26, 2010 Renaissance Montgomery Hotel at the Conference Center Montgomery, AL BOARD CHAIR LETTER It is my pleasure to welcome each of you to the Fourth Membership Meeting of the HBCU Library Alliance. Our conference theme, “Looking Back, Moving Forward: HBCU Libraries Using Digital Technologies to Reach, Teach and Connect,” speaks to the Alliance’s commitment of pursuing innovative ways of serving our students and faculty using cutting edge technology. Conference program offerings, which include using technology to complement library instruction, trace our roots, and preserve our history, emphasize the Alliance’s mission and vision to “be a consortium that promotes excellence in library leadership while preserving and promoting the history of the Historically Black College.” Beautiful Montgomery Alabama, a city “rich in history, yet focused on the future” is a perfect setting for our meeting. I hope that you will take the time to enjoy its southern hospitality by taking part in the Civil Rights Tour and Reception at the National Center for the Study of Civil Rights and African-American Culture. As we look back to our past, I ask you to join me in thanking our founding members — Loretta Parham, Janice Franklin, Emma Perry, Elsie Stephens Weatherington, and Tommy Holton — for their vision, and Kate Nevins and the LYRASIS (formerly SOLINET) Board for their support. It is because of them that we have a robust and vibrant organization. -

HBCU Library Alliance Completes Fourth Phase of Leadership Institute

PRESS RELEASE CONTACT: Sandra Phoenix HBCU Library Alliance Executive Director 404.592.4820 [email protected] HBCU Library Alliance Completes Fourth Phase of Leadership Institute Atlanta, Georgia – December 6, 2012 - The Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) Library Alliance completed the fourth phase of its Leadership Institute. The Leadership Institute, part of the larger HBCU Library Alliance Leadership Program, is a nine-month program funded by a $600,000 grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to develop and support effective library leadership at HBCUs. The fourth phase, and last round funded by the Foundation, builds on previous successes to further strengthen HBCU libraries and staff leadership skills. The nine-month Leadership Institute culminated in a four-day conference, held on November 8-11, 2012 in Atlanta, GA. Leadership Institute participants were selected with assistance by HBCU Library Alliance Board Chair Mary Jo Fayoyin, Savannah State University (GA) and Board Vice-Chair Cynthia Henderson, Howard University (DC). Participants presented their projects to the larger group during the conference, and represented the following HBCU Library Alliance institutions: Alabama State University, Bennett College (NC), Claflin University (SC), Coahoma Community College (MS), Delaware State University, Johnson C. Smith University (NC), Lincoln University (MO), Mississippi Valley State University, Saint Augustine’s College (NC), Savannah State University (GA), University of the Virgin Islands, West Virginia State University and Winston-Salem State University (NC). The theme for the conference was a Call to Action and focused on energizing library leadership in HBCUs. The keynote speaker was Dr. Sandra Casey-Buford, Director of Diversity and Inclusion from the Massachusetts Port Authority. -

Digital Library Federation and HBCU Library Alliance Name 2017 DLF HBCU Fellows

Digital Library Federation and HBCU Library Alliance Name 2017 DLF HBCU Fellows IMLS grant supports collaboration between organizations, travel fellowships, and HBCU/DLF Liberal Arts Preconference Washington, DC, September 20, 2017—Twenty-four individuals, primarily from historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) or with HBCU backgrounds, will attend the 2017 Digital Library Federation (DLF) Forum and DLF Liberal Arts/HBCUs Preconference in October, thanks to a grant of fellowship funds from the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Laura Bush 21st Century Librarian Program. The fellowships, totaling $37,836 in DLF and IMLS funding, are part of a larger IMLS grant of $49,950 to promote collaboration between the Digital Library Federation and HBCU Library Alliance communities, subsidize a joint conference, and expand HBCU participation at two DLF signature events. The DLF Forum preconference, held October 22 in Pittsburgh, will focus on digital libraries and library-based teaching as a common mission and common ground between liberal arts colleges or programs and HBCUs. The keynote speaker, Loretta Parham, directs Atlanta University Center’s Woodruff Library, which serves a consortium of Atlanta-area HBCUs. The annual DLF Forum follows the preconference from October 23-25, and will be keynoted by Afrofuturist writer, lawyer, and community organizer Rasheedah Phillips. Approximately 120 participants are expected to attend the preconference, which is structured to maximize informal conversation, relationship-building, and exchange. The DLF Forum will feature peer-reviewed panels and presentations on digital library technologies and practices, and typically attracts more than 600 attendees. DLF will additionally host meetings and conferences of the National Digital Stewardship Alliance (NDSA), Taiga Forum, Collections as Data team, and others, October 25-26. -

HBCU Brochure.Qxp

Students in Seminary class at Bennett College for Women, image from The HBCU Digital Collection FELLOW ALLIANCE MEMBERS, It is with great pleasure, and on behalf of the entire Board of Directors, that I welcome you to the HBCU Library Alliance 3rd Membership Meeting! Mary Jo Fayoyin (Savannah State), Membership Meeting Chair, and her team members have "raised the bar" and put together an exciting and informative agenda for this meeting. The team, and our Program Director, Sandra Phoenix, are to be congratulated. I know you join me in extending appreciation and admiration to them for their diligence and commitment. At the 2006 meeting in Savannah, Georgia, we discussed possible strategic move- ments to advance the HBCU Library Alliance. I am excited to report that the HBCU Library Alliance is actively involved in a number of projects that are creating oppor- tunities for visibility and partnerships. With your input, this meeting will reveal inno- vative directions for strategic planning and new approaches to advance HBCU Library Alliance projects. There is also great potential to increase the networking and collaboration among Alliance members. As we celebrate the third Membership Meeting of the HBCU Library Alliance, I chal- lenge you to move toward "more direct action and involvement." I challenge you to sharpen and elevate your advocacy skills in support of our institutions and the HBCU Library Alliance. Your contributions and participation are essential to the vitality and strength of the HBCU Library Alliance. Sunday is dedicated to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation sponsored Preservation Pre-Conference; I hope to see you there. -

HBCU Library Alliance—Cornell University Library Digitization Initiative Update

HBCU Library Alliance—Cornell University Library Digitization Initiative Update 2006 Facts about the Initiative: • Ten HBCU libraries have been selected for participation in • The goal of the Initiative is to train a cadre of this initial project. HBCU librarians and archivists in collaborative • The collaborative partnership includes training, digitization digital collection building. and storage, collection management and access, and assessment. HBCU librarians learn how to digitize Cornell University Library and HBCU Library select holdings for research and Alliance awarded collaborative Andrew W. Mellon scholarship Foundation grant to create digital library Atlanta, GA–Scholars and researchers will Ithaca, NY—With a $400,000 grant Grambling State University, gain increased access to historically black from the Andrew W. Mellon Hampton University, Southern college and university (HBCU) archival Foundation, Cornell University University, Tuskegee University, materials through the HBCU-CUL Digitization Library is partnering with the Tennessee State University, and Initiative. Historically Black College and Virginia State University. They Universities Library Alliance in a were selected based upon a The 18-month project began with a training digital collections initiative that will combination of institutional seminar on digital imaging held November lay the foundation for a future commitment to the project, the 14-18, 2005 at the Georgia Archives in HBCU digital library. richness of their holdings that Morrow, Ga. In a series of hands-on labs speak to the legacy of HBCUs, utilizing $70,000-worth of grant-funded In November, Cornell librarians led previous participation in the HBCU equipment, the seminar included best a training program in digital Archives Institute, and practices, models of digital imaging, imaging techniques for archivists geographical and institutional discussion of various hardware, software and librarians from ten historically diversity. -

@Famulibraries.Edu V2 Iss1

@famulibraries.edu http://www.famu.edu/library THE NEWSLETTER OF THE FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES Volume 2 Issue 1 Aug. / Sept. 2005 “Striking for Excellence in Library and Information Services” Fall Semester 2005 Friends of Libraries Honor Bryant and Byars Dates to Remember By Theresa Davis Senior Public Relations Major Friends of the FAMU Libraries held their annual award gala on Friday, July 15 at the Tallahassee – Leon County Civic Center. The gala is held yearly to honor and present Friends of the FAMU Libraries Awards to outstanding community leaders and achievers, and to give thanks and recognition to the librarians and support staff who keep Florida A&M’s libraries up to speed on the information super-highway. Friends of the FAMU First Day of Classes 8/29 Libraries president, Margaret B. Jones, describes the event as “…a fundraising activity de- FAMU vs. Delaware State 9/3 signed in support of the mission and programs of the organization.” This year’s theme was Labor Day Holiday 9/5 “Saluting Twenty-First Century Pacesetters.” Veteran’s Day 11/11 The Friends Award recipients for 2005 were FAMU’s interim president, Dr. Castell Vaughn Thanksgiving Holidays 11/24-25 Bryant, and celebrated author, Patti Wilson Byars. This year’s Librarian of the Year award Last Day of Classes 12/9 went to the library Acquisitions Department Supervisor, Ernestine Holmes. Dale Thomas of Final Examinations 12/12-16 Special Collections received the Library Support Staff of the Year award. Director of FAMU’s libraries, Dr. Lauren B. Sapp, presented both sets of awards. -

Annual Report 2016 Dear Members You Are Reading Our First Annual Report Since 2009

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Transforming LYRASIS LYRASIS supports enduring access to our shared academic, scientific and cultural heritage through leadership in open technologies, content services, digital solutions and collaboration with archives, libraries, museums and knowledge communities worldwide. LYRASIS: Annual Report 2016 Dear Members You are reading our first annual report since 2009. For me, I embark upon my second year at LYRASIS, knowing that each day brings a new opportunity to not only support, but to act, to advocate and to lead with our members. For LYRASIS, it is a celebration of the 80th anniversary of our humble historical beginnings, when PALINET (1936) and SOLINET (1937) emerged from the WPA efforts during the Great Depression. And, for you, this means you are a part of the most dynamic, uniquely diverse cultural heritage membership organization around that is focused on transforming the ways your institution can serve your community better. You will read about how our past year of transformation, transition and restructuring has benefited you. You will get a sense of where we are headed as we work together to change how content and knowledge is shared, is preserved and even distributed in ways that will allow our institution to be open, relevant and future-proofed in ways that might not be possible when acting alone. 2 LYRASIS: Annual Report 2016 Here are some of my favorite accomplishments undertaken on your behalf. Value – We are committed to offering more value to you. Three examples to showcase this focus: Over $10 million of savings with group purchasing; a reduction of over 10% in the cost of storage and migration services, and over 300,000 hours of training. -

(Hbcu) Photograph Preservation Project

HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES (HBCU) PHOTOGRAPH PRESERVATION PROJECT a program of the conservation center for Art & Historic artifacts, university of Delaware, lyrasis, and hbcu library alliance, with funding from the andrew w. mellon foundation PROJECT OVERVIEW CCAHA worked with LYRASIS, the University of Delaware, and the HCBU Library Alliance in an initiative to improve the preservation of significant photographic collections held within Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). "These collections document the visual and institutional history and legacy of HBCUs and form a core of primary research for the study of African American history," said Kate Nevins, Executive Director of LYRASIS. / 3 FAYETTEVILLE STATE UNIVERSITY project overview As the first publicly funded school for African Americans in the state of North Carolina, Fayetteville State University is home to a collection rich with historic photographs, scrapbooks, books, and other materials that document the period from the Era of Reconstruction through the Civil Rights Movement. This grant provided FSU’s Charles Waddell Chestnutt Library with the opportunity to preserve the photographic history of the University through the stabilization, conservation and re-housing of historic scrapbooks, slides, and photographs. One of the many scrapbooks from past president, Dr. Rudolph Jones accomplishments (1956-1969) that have been identified for conservation and preservation. This one shows Dr. Jones, other faculty, administrators All in-house projects identified in the and students at Fayetteville State College in the 1960’s. grant were completed on or before schedule. In order to accomplish all projected goals, staff members at Fayetteville State University recruited, hired and trained new staff; scrapbooks were stabilized and re-housed in appropriate enclosures. -

February 4, 2005 for Immediate Release Contact: Loretta Parham, (404) 978-2000 Or [email protected]

February 4, 2005 For Immediate Release Contact: Loretta Parham, (404) 978-2000 or [email protected] LILLIAN LEWIS HIRED AS PROGRAM OFFICER FOR THE HBCU LIBRARY ALLIANCE Lillian Lewis became the HBCU Library Alliance Program Officer on February 1, 2005. She will be responsible for the operation of the HBCU Library Alliance (www.hbculibraries.org), which was formed after a historic meeting in 2002 of the deans and directors of libraries at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). In addition, Ms. Lewis will coordinate and conduct a two-year project to strengthen leadership within the HBCU library community and more effectively integrate library services into campus programs for teaching and learning. The project is supported by a $500,000 grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Ms. Lewis has served as an administrator in associations, academic libraries, and special libraries. Most recently, she worked for the American Library Association as Deputy Executive Director jointly of the Association of Specialized and Cooperative Library Agencies and the Reference and User Services Association. Ms. Lewis’ background includes operational and strategic planning in library and community organizations; speaking on recruitment of traditionally underserved populations; and coordinating community projects and services that benefit children, adults, families, and professionals who serve them. Ms. Lewis is completing her Certificate in Strategies for Nonprofit Management at the University of Chicago. She holds a Master of Librarianship from Emory University and a Bachelor of Science degree from Spelman College. The HBCU Library Alliance seeks to ensure excellence in HBCU libraries through the development, coordination, and promotion of programs and activities to enhance members’ collections and services. -

The Treasures Held by Hbcus Are Astounding. Here's Just a Sampling

Art i facts Summer 2021 LEFT An after-treatment reference photograph of the Lem Hawkins’ Confession lobby card RIGHTTigerbelle track team and Coach Edward S. Temple with medals from a 1958 meet in Moscow, courtesy of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Special Collections. Building Capacity: The HBCU Library Alliance and CCAHA Nine years before the first shot of the Civil War, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania was founded, now viewed as the nation’s first still-operating HBCU (Historically Black College and University). As 100+ more HBCUs steadily opened—spread across 19 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands—the academic libraries within the HBCUs found themselves serving as repositories for the historical documents of their faculty, alumni, and communities. Looking back now, many of these documents are true treasures. They record and preserve a history too long overlooked and disregarded. The HBCU libraries and their archives offer irreplaceable documentation of the African-American experience in the 19th and 20th century centuries, reflecting the monumental themes of slavery, Civil War, Restoration, the Great Migration, the Harlem Renaissance, the Civil Rights Movement, Black Lives Matter, and so much more. Complementing these broad themes, the HBCU special collections also spotlight the contributions of individuals in countless fields—from science to politics and from arts to athletics—with the work of very familiar names preserved alongside lesser-known figures who nonetheless left material that can offer unparalleled insight into their time or area of expertise. For more than a decade, CCAHA has been honored to work side-by-side with the HBCU Library Alliance, a consortium dedicated to strengthening the libraries and archives at 76 member HBCUs. -

2018 Jackson Program

25th NATIONAL HBCU FACULTY DEVELOPMENT NETWORK CONFERENCE "Programs for Enhancing Quality: Strategies that Work" Jackson Marriott Hotel Jackson, Mississippi November 1-3, 2018 2 3 25th National HBCU Faculty Development Network Symposium Program "Programs for Enhancing Quality: Strategies that Work" November 1-3, 2018 Thursday Pre-Conference: Donna Elmore-Cole Sarah Richardson “Grant Writing” Friday Breakfast Guest Speaker: Jahmad Canley Do they really BELIEVE they can Achieve? Friday Luncheon Guest Speaker: Fulbright Internationalize your Campus through the Fulbright Scholar Program Saturday Breakfast Plenary Speaker: Saturday Luncheon Speakers: W. Joye Hardiman A Soul Comes Home: Reversing the Seasoning Process - Strategies for Indigestibility when in the Belly of the Higher Education Beas Sponsors: Council on Foreign Relations Achieving the Dream MVS Consultants Local Institutions: Jackson State University 4 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Brain-based Teaching and Leadership Coach Henry J. Findlay (President) Tuskegee University Learning Across the Curriculum Patricia Brooks (Secretary) Jackson, TN Assessment & Diversity Donald Collins (Treasurer) Prairie View A&M University Library Services Sandra Phoenix (Board Member) HBCU Library Alliance Clarissa Myrick-Harris (Board Member) OWA Institute Faculty Development and Learning Communities Laurette B. Foster (Executive Director) Prairie View A&M University Past Presidents’ Advisory Committee Members Phyllis Worthy Dawkins (Past President and Co-Founder), President Bennett College Henry J. Findlay, -

NEH Application Cover Sheet Infrastructure and Capacity Building

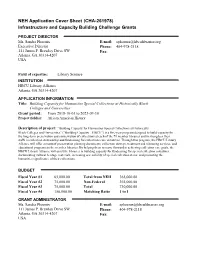

NEH Application Cover Sheet (CHA-261978) Infrastructure and Capacity Building Challenge Grants PROJECT DIRECTOR Ms. Sandra Phoenix E-mail: [email protected] Executive Director Phone: 404-978-2118 111 James P. Brawley Drive SW Fax: Atlanta, GA 30314-4207 USA Field of expertise: Library Science INSTITUTION HBCU Library Alliance Atlanta, GA 30314-4207 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Building Capacity for Humanities Special Collections at Historically Black Colleges and Universities Grant period: From 2018-10-01 to 2023-09-30 Project field(s): African American History Description of project: “Building Capacity for Humanities Special Collections at Historically Black Colleges and Universities” (“Building Capacity – HBCU”) is a five-year program designed to build capacity for the long-term preservation and conservation of collections at each of the 71 member libraries and to strengthen their staffs in collection stewardship and fundraising for collections care initiatives. Through this program, the HBCU Library Alliance will offer a menu of preservation planning documents, collection surveys, treatment and rehousing services, and educational programs to the member libraries. By helping them to move forward in achieving collection care goals, the HBCU Library Alliance will assist the libraries in building capacity for fundraising for special collection initiatives, documenting cultural heritage materials, increasing accessibility of special collection items, and promoting the humanities significance of their collections. BUDGET Fiscal Year #1 65,000.00 Total from NEH 365,000.00 Fiscal Year #2 75,000.00 Non-Federal 365,000.00 Fiscal Year #3 75,000.00 Total 730,000.00 Fiscal Year #4 150,000.00 Matching Ratio 1 to 1 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms.