House Sexual Discrimination and Harassment Task Force Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illinois American Job Centers

I LL I NO I S A MER I C A N J OB C ENTERS — C ONT A CT I NFORM A T I ON Illinois American Job Centers LWIA 1 Renee Renken, Dana Washington, Director LWIA 19 Kevin Pierce, WIOA Assistant Director for Kankakee Workforce Services Services Representative Laura Gergely, Workforce Development 450 N. Kinzie Avenue Workforce Investment Solutions Phone: 217-238-8224 Coordinator Kane County Office of Bradley, IL 60915 757 W. Pershing Rd. E-mail: kpierce69849@ Lake County Workforce Community Reinvestment Phone: 815-802-8964 Springcreek Plaza lakelandcollege.edu Development Board 1 Smoke Tree Office Complex, E-mail: [email protected] Decatur, IL 62526 1 N. Genesee Street, 1st Floor Unit A LWIA 24 Waukegan, IL 60085 North Aurora, IL 60542 LWIA 13 Rocki Wilkerson, Phone: 847-377-2234 Phone: 630-208-1486 Executive Director St. Clair County E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: renkenrenee@ Rock Island Phone: 217-875-8720 Intergovernmental countyofkane.org Tri-County Consortium E-mail: [email protected] Grants Department Jennifer Serino, 19 Public Square, Suite 20 1504 Third Avenue, Room 114 Karen Allen, Director LWIA 6 Rock Island, IL 61201 Belleville, IL 62220 Lake County Workforce Program Manager Phone: 217-875-8281 Rick Stubblefield, Development Lisa Schvach, Director Mark E. Lohman, E-mail: [email protected] Executive Director Phone: 847-377-2224 DuPage County Workforce Executive Director Phone: 618-825-3203 E-mail: [email protected] Development Division Phone: 309-793-5206 LWIA 20 E-Mail: rstubblefield@ 2525 Cabot Drive, Suite 302 E-mail: Mark.Lohman@ LWIA 2 AmericanJob.Center co.st-clair.il.us Lisle, IL 60532 Sarah Graham, Phone: 630-955-2044 ® Matt Jones, Morris Jeffery Poynter, WIB Director American Job Center Executive Director E-mail: lschvach@ Program Coordinator, McHenry County Phone: 309-788-7587 Land of Lincoln worknetdupage.org Workforce Development Group Workforce Network Board Phone: 309-852-6544 Workforce Alliance Phone: 618-825-3254 500 Russel Court 1300 S. -

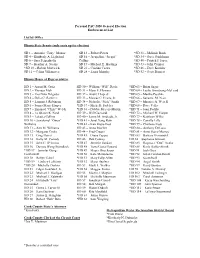

Denotes Contested Primary Races Personal PAC Preliminary

Personal PAC Preliminary 2020 Primary Election Endorsement List As of January 14, 2020 List by Office Illinois State Senate (only seats up for election) *SD 1 – Antonio Munoz SD 16 – Jacqueline Collins *SD 40 – Patrick Joyce SD 4 – Kimberly Lightford SD 19 – Michael Hastings SD 43 – John Connor SD 7 – Heather Steans *SD 22 – Cristina Castro SD 46 – Dave Koehler *SD 10 – Robert Martwick SD 28 – Laura Murphy SD 52 – Scott Bennett SD 11 – Celina Villanueva SD 31 – Melinda Bush *SD 13 – Robert Peters SD 34 – Steve Stadelman Illinois House of Representatives *HD 1 – Aaron Ortiz *HD 31 – Mary Flowers HD 64 – Leslie Armstrong-McLeod *HD 2 – Theresa Mah *HD 32 – Andre Thapedi *HD 65 – Martha Paschke HD 4 – Delia Ramirez HD 33 – Marcus Evans *HD 66 – Suzanne Ness HD 5 – Lamont Robinson HD 34 – Nicholas Smith HD 67 – Maurice West HD 6 – Sonya Harper HD 37 – Michelle Fadeley HD 68 – Dave Vella HD 7 – Emanuel "Chris" Welch HD 38 – Debbie Meyers-Martin HD 71 – Joan Padilla HD 8 – LaShawn Ford HD 39 – Will Guzzardi HD 72 – Michael Halpin *HD 10 – Jawaharial Williams *HD 40 – Jaime Andrade HD 77 – Kathleen Willis HD 11 – Ann Williams *HD 41 – Janet Yang Rohr HD 78 – Camille Lilly *HD 12 – Sara Feigenholtz HD 42 – Ken Mejia-Beal *HD 79 – Charlene Eads HD 13 – Gregory Harris HD 43 – Anna Moeller HD 80 – Anthony DeLuca HD 14 – Kelly Cassidy HD 44 – Fred Crespo HD 81 – Anne Stava-Murray HD 15 – John D'Amico HD 45 – Diane Pappas *HD 83 – Barbara Hernandez *HD 16 – Denyse Wang Stoneback HD 46 – Deb Conroy HD 84 – Stephanie Kifowit HD 17 – Jennifer Gong-Gershowitz -

Installment Sales Contract Act Protecting Rent-To-Own Homebuyers

Public Act 100-0416: Installment Sales Contract Act Protecting Rent-to-Own Homebuyers New Illinois Law Goes into Effect on January 1, 2018 In the aftermath of the foreclosure crisis, there has been a resurgence in “rent-to-own” housing opportunities (a.k.a. contracts for deed or real estate installment contracts) promising homeownership to people who generally are not in a financial position to buy a home through securing a mortgage. While rent-to-own can be an understandable choice for certain buyers, prior to passage of this new state law, rent-to-own contracts were only minimally regulated under Illinois law and prone to contain misleading and/or unfair terms and conditions. Even worse, some sellers of rent-to-own homes have a business model based on predatory practices that churn a series of buyers through unsustainable agreements that quickly lead to default. Key consumer protection provisions in Public Act 100-0416 include: Disclosures and Education Prior to the Sale • Creates Installment Sales Contract Act regulating sellers of 1-4 unit residential properties who enter into contracts more than 3 times in any 12-month period. • Requires a written contract for these sales that must include certain information, including any balloon payments due. • Requires the buyer to receive an amortization schedule prior to closing, so they understand how much of their monthly payment will be applied to principal and interest and how long it will take to pay off the loan. • Requires disclosure of building code violations and fair cash value, as reflected on tax bills, so that prospective buyers have some sense of the condition and value of the home. -

*Denotes a Contested Race Personal PAC 2020 General Election Endorsement List

Personal PAC 2020 General Election Endorsement List List by Office Illinois State Senate (only seats up for election) SD 1 – Antonio “Tony” Munoz SD 13 – Robert Peters *SD 31 – Melinda Bush SD 4 – Kimberly A. Lightford SD 16 – Jacqueline “Jacqui” *SD 34 – Steve Stadelman SD 6 – Sara Feigenholtz Collins *SD 40 – Patrick J. Joyce SD 7 – Heather A. Steans SD 19 – Michael E. Hastings *SD 43 – John Connor *SD 10 – Robert Martwick SD 22 – Cristina Castro *SD 46 – Dave Koehler SD 11 – Celina Villanueva SD 28 – Laura Murphy *SD 52 – Scott Bennett Illinois House of Representative HD 1 – Aaron M. Ortiz HD 30 – William “Will” Davis *HD 63 – Brian Sager HD 2 – Theresa Mah HD 31 – Mary E. Flowers *HD 64 – Leslie Armstrong-McLeod HD 3 – Eva Dina Delgado HD 32 – André Thapedi *HD 65 – Martha Paschke HD 4 – Delia C. Ramirez HD 33 – Marcus C. Evans, Jr. *HD 66 – Suzanne M. Ness HD 5 – Lamont J. Robinson HD 34 – Nicholas “Nick” Smith *HD 67 – Maurice A. West II HD 6 – Sonya Marie Harper *HD 37 – Michelle Fadeley *HD 68 – Dave Vella HD 7 – Emanuel "Chris" Welch *HD 38 – Debbie Meyers-Martin *HD 71 – Joan Padilla HD 8 – La Shawn K. Ford HD 39 – Will Guzzardi *HD 72 – Michael W. Halpin HD 9 – Lakesia Collins HD 40 – Jaime M. Andrade, Jr. *HD 77 – Kathleen Willis HD 10 – Jawaharial “Omar” *HD 41 – Janet Yang Rohr *HD 78 – Camille Lilly Williams *HD 42 – Ken Mejia-Beal *HD 79 – Charlene Eads HD 11 – Ann M. Williams HD 43 – Anna Moeller *HD 80 – Anthony DeLuca HD 12 – Margaret Croke HD 44 – Fred Crespo *HD 81 – Anne Stava-Murray HD 13 – Greg Harris *HD 45 – Diane Pappas *HD 83 – Barbara Hernandez HD 14 – Kelly M. -

Illinois House by Name

102nd Illinois House of Representatives Listing by Name as of 2/1/2021 Name District Party Name District Party Carol Ammons 103 D Mark Luft 91 R Jaime M. Andrade, Jr. 40 D Michael J. Madigan 22 D Dagmara Avelar 85 D Theresa Mah 2 D Mark Batinick 97 R Natalie A. Manley 98 D Thomas M. Bennett 106 R Michael T. Marron 104 R Chris Bos 51 R Joyce Mason 61 D Avery Bourne 95 R Rita Mayfield 60 D Dan Brady 105 R Deanne M. Mazzochi 47 R Kambium Buckner 26 D Tony McCombie 71 R Kelly M. Burke 36 D Martin McLaughlin 52 R Tim Butler 87 R Charles Meier 108 R Jonathan Carroll 57 D Debbie Meyers-Martin 38 D Kelly M. Cassidy 14 D Chris Miller 110 R Dan Caulkins 101 R Anna Moeller 43 D Andrew S. Chesney 89 R Bob Morgan 58 D Lakesia Collins 9 D Thomas Morrison 54 R Deb Conroy 46 D Martin J. Moylan 55 D Terra Costa Howard 48 D Mike Murphy 99 R Fred Crespo 44 D Michelle Mussman 56 D Margaret Croke 12 D Suzanne Ness 66 D John C. D'Amico 15 D Adam Niemerg 109 R C.D. Davidsmeyer 100 R Aaron M. Ortiz 1 D William Davis 30 D Tim Ozinga 37 R Eva Dina Delgado 3 D Delia C. Ramirez 4 D Anthony DeLuca 80 D Steven Reick 63 R Tom Demmer 90 R Robert Rita 28 D Daniel Didech 59 D Lamont J. Robinson, Jr. 5 D Jim Durkin 82 R Sue Scherer 96 D Amy Elik 111 R Dave Severin 117 R Marcus C. -

Legislative Report Card

Legislative Report Card IMA LEGISLATIVE RATINGS FOR 2019-20 BOLDLY MOVING MAKERS FORWARD LEGISLATIVE OVERVIEW IMA by the Mark Denzler President & CEO Numbers: Every year, the Illinois General Assembly votes on thousands of bills and amendments, many of which have an impact on the manufacturing sector. While the global 9,822 pandemic curtailed much of the spring legislative session in 2020, it Bills introduced showcased the need for a strong and vibrant manufacturing sector in the United States. Manufacturers are answering our nation’s call and in the 2019-20 leading the way forward through the worst economic and health crisis in legislative session generations and we need policies that support American manufacturing. The IMA’s Legislative Report Card will showcase the lawmakers supportive of Illinois’ manufacturing economy and those that vote against job creators. We often hear political rhetoric from legislators that claim to support jobs and investment but then their actions don’t back 895 their words. Bills lobbied by the Does your legislator support manufacturing? Did your legislator vote IMA for the $3.5 billion graduated income tax hike? Do they oppose costly regulations or support manufacturing innovation? The IMA believes it is important for employers, employees, and Illinois residents to know exactly where their lawmakers stand on issues 34 important to the business community. This objective Legislative Report Card will let you know whether your local lawmakers supported the Roll call votes in the manufacturing sector, and large business community, on critically scorecard important issues related to tax policy, environmental regulations, workers’ compensation, labor law, transportation, and more. -

2020 Election Results

NEWS FROM THE FRONT - ELECTION EDITION 11/04/2020 Many election day contests in Illinois remain undecided as of Wednesday afternoon. With record-setting vote-by-mail ballots requested this year, the Illinois State Board of Elections is advising that the unofficial vote totals reported on election night may change, perhaps significantly, in the next two weeks. Approximately 587,000 vote-by-mail-ballots were still outstanding as of November 2. The results in many close races may not be known until November 17, after all vote-by-mail and provisional ballots are counted. Final results will be certified by the State Board of Elections on December 4. We will continue to update you as results in individual races are finalized. Graduated Income Tax Fails The statewide ballot initiative to amend the Illinois Constitution to allow for a graduated income tax failed by a vote of 45% of those voting on the question in favor to 55% opposed. CBAI appreciates the strong partnership we have had with the Illinois Farm Bureau, Illinois Retail Merchants and Illinois Manufacturers’ who have banded together over the last year and a half to educate lawmakers and voters about the negative impact a progressive income tax would have on main street employers. CBAI also contributed to and participated in the Coalition to Stop the Proposed Tax Increase which effectively rebuffed efforts to amend the constitution. Governor JB Pritzker supported and strongly advocated for the constitutional amendment to change the Illinois income tax system from a “flat” tax to a “progressive income” tax targeting wealthier Illinoisans. -

All Bills Passed Both Houses with Last Action

STATE OF ILLINOIS LEGISLATIVE INFORMATION SYSTEM 102nd GENERAL ASSEMBLY TOTAL Synopsis of Legislation Legislation Passed Both Houses with Last Action All legislation through October 02, 2021 10/02/21 Legislative Information System 3:30:23 102ndGeneral Assembly Page: 002 Synopsis of Legislation Passed Both Houses All legislation through October 02, 2021 HB 00004 Rep. Rita Mayfield, Janet Yang Rohr, Margaret Croke, Sue Scherer and Stephanie A. Kifowit (Sen. Adriane Johnson, Sally J. Turner-David Koehler and Julie A. Morrison-Patricia Van Pelt) 105 ILCS 5/10-20.56 Amends the School Code. Permits student instruction to be received electronically under a school district's program for e-learning days while students are not physically present because a school was selected to be a polling place under the Election Code. Senate Floor Amendment No. 2 Replaces everything after the enacting clause. Reinserts the contents of the bill, but adds that a school district shall pay to its contractors who provide educational support services to the district their daily, regular rate of pay or billings rendered for any e-learning day that is used because a school was selected to be a polling place. Provides that this requirement does not apply to contractors who are paid under contracts that are entered into, amended, or renewed on or after March 15, 2022 or to contracts that otherwise address compensation for such e-learning days. Aug 27 21 H Public Act . 102-0584 HB 00012 Rep. Terra Costa Howard-Katie Stuart-Jaime M. Andrade, Jr.-Marcus C. Evans, Jr.-Kathleen Willis, Tony McCombie, Deb Conroy, Anna Moeller, Martin J. -

Undergraduate Scholarship Application

ILLINOIS LEGISLATIVE BLACK CAUCUS FOUNDATION 2017 - Undergraduate Scholarship Application ILBC Board Members Scholarship Eligibility: JOINT CAUCUS CHAIRMAN This application is for students seeking an undergraduate degree. Applicants SEN. KIMBERLY A. LIGHTFORD should be an accepted student at an accredited institution of higher learning to SENATE BLACK CAUCUS CHAIRMAN include community colleges, private institutions and certified vocational training SEN. TOI HUTCHINSON programs. HOUSE BLACK CAUCUS CHAIRMAN REP. CAMILLE LILLY ILBC Members, ILBC employees, ILBC Foundation board members, and their ILBC TREASURER immediate relatives are ineligible for the scholarship program. REP. ELGIE SIMS ILBC SECRETARY How to Apply: REP. LITESA WALLACE You can email the Illinois Legislative Black Caucus Foundation Scholarship ILBC SGT. AT Selection Committee at [email protected] to request an application. ARMS/PARLIMENTARIAN REP. SONYA HARPER All applicants must: CAUCUS MEMBERS Be an Illinois resident REP. CAROL AMMONS Complete the ILBCF Undergraduate Scholarship Application SEN. JAMES CLAYBORNE JR. SEN. JACQUELINE Y. COLLINS Submit verification of college enrollment or letter of acceptance REP. MONIQUE DAVIS Write a personal statement (500 words or less) describing interest and REP. WILL DAVIS REP. MELISSA CONYEARS-ERVIN involvement in community and public service, hobbies, talents, sports and/or REP. MARCUS EVANS school activities. The statement should address future academic and REP. MARY FLOWERS REP. LASHAWN FORD professional career plans and may highlight any personal challenge(s) REP. LATOYA GREENWOOD perspective has overcome REP. JEHAN GORDON-BOOTH SEN. NAPOLEON HARRIS III Submit high school transcript (if in college, current transcript) SEN. MATTIE HUNTER SEN. TOI HUTCHINSON Submit two letters of recommendation from persons other than relatives SEN. -

2018 Economic Impact Statement

2018 BUCK STAYS THE HERE EDUCATION & ADVOCACY INITIATIVE Understanding the economic impact of CTPF benefit payments on the State of Illinois and the City of Chicago EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PURPOSE OF REPORT This report examines the impact that Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund (CTPF) educators have outside the classroom, and the economic benefit pensions have on CTPF Pensions“ help the City of Chicago and the State of Illinois. support 14,704 jobs A study was conducted which examined CTPF members and their benefit payments by legislative district. Information from this study, contained in the first half of this in the State of Illinois report, is shown for legislators in the State of Illinois along with Aldermen in the City of Chicago. including 7,500 in The second half of this report includes additional information about CTPF’s the City of Chicago. members and priorities, and additional information on some of CTPF’s key investment initiatives. RESULTS The study shows that about 84% of CTPF annuitants live in the State of Illinois, and ” about 50% of those annuitants live in the City of Chicago. CTPF benefit payments contribute: • $1.3 billion in direct payments to annuitants in the State of Illinois • $1.9 billion in total economic impact in the State of Illinois • $687 million in payments to annuitants in the City of Chicago • $1.0 billion in total economic impact on the City of Chicago Pension benefit payments and their ripple effect help support jobs including: CTPF BOARD OF TRUSTEES • 14,704 jobs in the State of Illinois Jay C. Rehak • 7,500 jobs in the City of Chicago President Lois W. -

Illinois AFL-CIO 2020 Primary Election Endorsements

Illinois AFL-CIO 2020 Primary Election Endorsements Italics – incumbent 8th – La Shawn Ford (D) 67th – Maurice West II (D) *- union member 9th – Lakesia Collins (D)* 68th – Dave Vella (D) 10th – Omar Williams (D)* 70th – Paul Stoddard (D)* Ballot question 11th – Ann Williams (D) 71st – Joan Padilla (D) Support Fair Tax Constitutional 12th – Margaret Croke (D) 72nd – Mike Halpin (D) Amendment 13th – Greg Harris (D) 74th – Christopher Demink (D)* 14th – Kelly Cassidy (D) 76th – Lance Yednock (D)* U.S. Senate 15th – John D’Amico (D)* 77th – Kathleen Willis (D) Dick Durbin (D) 16th – Yehiel “Mark” Kalish (D) 78th – Camille Lilly (D) 17th – Jennifer Gong-Gershowitz (D) 79th – Charlene Eads (D)* U.S. House 18th – Robyn Gabel (D) 80th – Anthony DeLuca (D) 1st – Bobby Rush (D) 20th – Michelle Darbro (D)* 81st – Anne Stava-Murray (D) 2nd – Robin Kelly (D) 20th – Brad Stephens (R)* 83rd – Barbara Hernandez (D) 3rd – Dan Lipinski (D) 21st – Edgar Gonzalez (D) 84th – Stephanie Kifowit (D) 4th – Chuy Garcia (D) 22nd – Michael Madigan (D) 85th – Dagmara “Dee” Avelar (D)* 5th – Mike Quigley (D) 23rd – Mike Zalewski (D) 86th – Larry Walsh Jr (D)* 6th – Sean Casten (D) 24th – Lisa Hernandez (D) 88th – Karla Bailey-Smith (D) 7th – Danny Davis (D) 25th – Curtis Tarver II (D) 90th – Seth Wiggins (D) 8th – Raja Krishnamoorthi (D) 26th – Kam Buckner (D) 91st – Mark Luft (R) 9th – Jan Schakowsky (D)* 27th – Justin Slaughter (D) 92nd – Jehan Gordon-Booth (D) 10th – Brad Schneider (D) 28th – Bob Rita (D) 93rd – Scott Stoll (D) 11th – Bill Foster (D) 29th – Thaddeus -

Illinois State House Districts 100Th General Assembly (2017-2018) First Session, 2017

Illinois State House Districts 100th General Assembly (2017-2018) First session, 2017 This document includes: Illinois State House districts map, statewide Illinois State House districts map, northeast Illinois List of Illinois State House districts, numerically by district, 2017 List of Illinois State House districts, alphabetically by representative, 2017 Post-Census 2010 districts After the 2010 Census, the Illinois state house and senate districts were redrawn in 2011. The number of districts remained the same as for the post-Census 2000 districts, but the boundaries of the districts changed. These new districts were used as the basis for the general election held in November 2012. The new districts took effect with the beginning of the 98th General Assembly, Session One, in January 2013. They remain in effect through the end of the 102nd General Assembly, Session Two, in 2022. For additional information: Illinois General Assembly http://www.ilga.gov/ Illinois State House districts, representatives listed numerically by district, 2017 Grant Wehrli 41 R Representative Dist. Party Jeanne M Ives 42 R Daniel J. Burke 1 D Anna Moeller 43 D Theresa Mah 2 D Fred Crespo 44 D Luis Arroyo 3 D Christine Winger 45 R Cynthia Soto 4 D Deborah Conroy 46 D Juliana Stratton 5 D Patricia R. Bellock 47 R Sonya M. Harper 6 D Peter Breen 48 R Emanuel Chris Welch 7 D Mike Fortner 49 R La Shawn K. Ford 8 D Keith Wheeler 50 R Arthur Turner 9 D Nick Sauer 51 R Melissa Conyears-Ervin 10 D David McSweeney 52 R Ann Williams 11 D David Harris 53 R Sara Feigenholtz 12 D Thomas Morrison 54 R Gregory Harris 13 D Martin J Moylan 55 D Kelly M.