Heads and Tails Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg's Corpora Of

This is a repository copy of Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg’s Corpora of Nomismata. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/124522/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Jarrett, J orcid.org/0000-0002-0433-5233 (2018) Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg’s Corpora of Nomismata. Numismatic Chronicle, 177. pp. 514-535. ISSN 0078-2696 © 2017 The Author. This is an author produced version of a paper accepted for publication in Numismatic Chronicle. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ REVIEW ARTICLE Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg’s Corpora of Nomismata* JONATHAN JARRETT FRANZ FÜEG, Corpus of the Nomismata from Anastasius II to John I in Constantinople 713–976: Structure of the Issues; Corpus of Coin Finds; Contribution to the Iconographic and Monetary History, trans. -

The Coins and Banknotes of Denmark

The Coins and Banknotes of Denmark Danmarks Nationalbank's building in Copenhagen was designed by the internationally renowned Danish architect Arne Jacobsen and built between 1965-1978 The Coins and Banknotes of Denmark, 2nd edition, August 2005 Text may be copied from this publication provided that This edition closed for contributions in July 2005. Danmarks Nationalbank is specifically stated as the sour- Print: Fr. G. Knudtzon's Bogtrykkeri A/S ce. Changes to or misrepresentation of the content are ISBN 87-87251-55-8 not permitted. For further information about coins and (Online) ISBN 87-87251-56-6 banknotes, please contact: Danmarks Nationalbank, Information Desk Havnegade 5 DK-1093 Copenhagen K Telephone +45 33 63 70 00 (direct) or +45 33 63 63 63 E-mail [email protected] www.nationalbanken.dk 2 Old and new traditions s the central bank of Denmark, Danmarks There are many traditions linked to the appearan- ANationalbank has the sole right to produce ce of banknotes and coins, but the designs are also and issue Danish banknotes and coins. Subject to subject to ongoing renewal and development. For the approval of the Minister for Economic and Bus- instance, the Danish banknote series has been iness Affairs, Danmarks Nationalbank determines upgraded with new security features – holograms the appearance of Danish banknotes and coins and fluorescent colours. The coin series has been and their denominations. supplemented with a tower series and a fairy tale This brochure provides a brief description – in text series, the latter also in silver and gold editions. As and pictures – of the process from the artist's first a consequence of these changes, the time has sketch until the banknotes and coins are put into come to update this publication. -

50 State Quarters Lesson Plans, Grades 9 Through 12

5: A World of Money Modern World History CLASS TIME Four 45- to 50-minute sessions OBJECTIVES Students will identify, recognize, and appreciate continuing global traditions related to the creation of national currencies. They will evaluate and analyze the role currency plays in shaping a national or regional identity. They will discuss and predict how regional, cultural, and national identity influences the designers of world currency. NATIONAL STANDARDS The standards used for these lesson plans reference the “10 Thematic Standards in Social Studies” developed by the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). • Culture—Students should be able to demonstrate the value of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups. Students should be able to construct reasoned judgments about specific cultural responses to persistent human issues. • Time, Continuity, and Change—Students should be able to investigate, interpret, and analyze multiple historical and contemporary viewpoints within and across cultures related to important events, recurring dilemmas, and persistent issues, while employing empathy, skepticism, and critical judgment. • Individual Development and Identity—Students should be able to articulate personal connections to time, place, and social and cultural systems. • Individuals, Groups, and Institutions—Students should be able to analyze group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture in both historical and contemporary settings. TERMS AND CONCEPTS: • The United States Mint 50 State Quarters® Program • Medium of exchange • Legal tender • Commemorative • Motto • Emblem • Symbolism • Nationalism • Patriotism • Circulating coin • Obverse (front) • Reverse (back) • Bust • Designer PORTIONS © 2004 U.S. MINT. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. 30 Grades 9 through 12 A World of Money SESSION 1 Materials • Chalkboard or whiteboard • Chalk or markers • Chart paper • Packets of U.S. -

Detail of a Silver Denarius from the Museum Collection, Decorated with the Head of Pax (Or Venus), 36–29 BCE

Detail of a silver denarius from the Museum collection, decorated with the head of Pax (or Venus), 36–29 BCE. PM object 29-126-864. 12 EXPEDITION Volume 60 Number 2 Like a Bad Penny Ancient Numismatics in the Modern World by jane sancinito numismatics (pronounced nu-mis-MAT-ics) is the study of coins, paper money, tokens, and medals. More broadly, numismatists (nu-MIS-ma-tists) explore how money is used: to pay for goods and services or to settle debts. Ancient coins and their contexts—including coins found in archaeological excavations—not only provide us with information about a region’s economy, but also about historical changes throughout a period, the beliefs of a society, important leaders, and artistic and fashion trends. EXPEDITION Fall 2018 13 LIKE A BAD PENNY Modern Problems, Ancient Origins Aegina and Athens were among the earliest Greek cities My change is forty-seven cents, a quarter, two dimes, to adopt coinage (ca. 7th century BCE), and both quickly and two pennies, one of them Canadian. Despite the developed imagery that represented them. Aegina, the steaming tea beside me, the product of a successful island city-state, chose a turtle, while on the mainland, exchange with the barista, I’m cranky, because, strictly Athens put the face of its patron deity, Athena, on the front speaking, I’ve been cheated. Not by much of course, (known as the obverse) and her symbols, the owl and the not enough to complain, but I recognize, albeit belat- olive branch, on the back (the reverse). They even started edly, that the Canadian penny isn’t money, not even in using the first three letters of their city’s name,ΑΘΕ , to Canada, where a few years ago they demonetized their signify: this is ours, we made this, and we stand behind it. -

Money Counts” Badge

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS ECONOMIC EDUCATION Girl Scout Daisy Activities to Earn the “Money Counts” Badge Activities Description Through these activities, girls examine U.S. coins, including coin design, value, and color. They differentiate among the coins, learn the obverse and reverse of coins, and play a bingo game reviewing the coins’ features. They examine paper money, learning about different denominations and which famous American’s portrait is on which bill. They play a game where they associate the price of a fun good or service with the appropriate payment. Girl Scout Program Level Daisy Concepts Coin and bill recognition Goods and services Obverse and reverse Spending Objectives Girls will be able to • define and identify the obverse and reverse of coins, • match the portrait on a bill with the denomination, • define and identify goods and services, and • identify the notes or coins needed to pay for specific goods and services. Time Required 30 minutes at two or three troop meetings, depending on the number of activities chosen ©2016, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Permission is granted to reprint or photocopy this lesson in its entirety for educational purposes, provided the user credits the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, www.stlouisfed.org/education. 1 Girl Scout Daisy Activities to Earn the “Money Counts” Badge Materials/Preparation • Handout 1: Coins, one copy, cut out, for each pair of girls (Alternatively, provide each pair of girls with two of each coin [penny, nickel, dime, quarter, and half- dollar]. If you use real coins, you will still need one copy of Handout 1 for each pair of girls but it will not need to be cut out.) Be sure the real coins have the same images as the coins in the activity. -

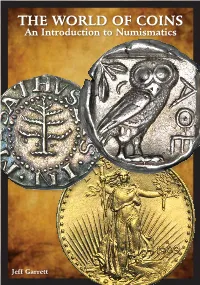

THE WORLD of COINS an Introduction to Numismatics

THE WORLD OF COINS An Introduction to Numismatics Jeff Garrett Table of Contents The World of Coins .................................................... Page 1 The Many Ways to Collect Coins .............................. Page 4 Series Collecting ........................................................ Page 6 Type Collecting .......................................................... Page 8 U.S. Proof Sets and Mint Sets .................................... Page 10 Commemorative Coins .............................................. Page 16 Colonial Coins ........................................................... Page 20 Pioneer Gold Coins .................................................... Page 22 Pattern Coins .............................................................. Page 24 Modern Coins (Including Proofs) .............................. Page 26 Silver Eagles .............................................................. Page 28 Ancient Coins ............................................................. Page 30 World Coins ............................................................... Page 32 Currency ..................................................................... Page 34 Pedigree and Provenance ........................................... Page 40 The Rewards and Risks of Collecting Coins ............. Page 44 The Importance of Authenticity and Grade ............... Page 46 National Numismatic Collection ................................ Page 50 Conclusion ................................................................. Page -

Detail of a Silver Denarius from the Museum Collection, Decorated with the Head of Pax (Or Venus), 36–29 BCE

Detail of a silver denarius from the Museum collection, decorated with the head of Pax (or Venus), 36–29 BCE. PM object 29-126-864. 12 EXPEDITION Volume 60 Number 2 Like a Bad Penny Ancient Numismatics in the Modern World by jane sancinito numismatics (pronounced nu-mis-MAT-ics) is the study of coins, paper money, tokens, and medals. More broadly, numismatists (nu-MIS-ma-tists) explore how money is used: to pay for goods and services or to settle debts. Ancient coins and their contexts—including coins found in archaeological excavations—not only provide us with information about a region’s economy, but also about historical changes throughout a period, the beliefs of a society, important leaders, and artistic and fashion trends. EXPEDITION Fall 2018 13 LIKE A BAD PENNY Modern Problems, Ancient Origins Aegina and Athens were among the earliest Greek cities My change is forty-seven cents, a quarter, two dimes, to adopt coinage (ca. 7th century BCE), and both quickly and two pennies, one of them Canadian. Despite the developed imagery that represented them. Aegina, the steaming tea beside me, the product of a successful island city-state, chose a turtle, while on the mainland, exchange with the barista, I’m cranky, because, strictly Athens put the face of its patron deity, Athena, on the front speaking, I’ve been cheated. Not by much of course, (known as the obverse) and her symbols, the owl and the not enough to complain, but I recognize, albeit belat- olive branch, on the back (the reverse). Tey even started edly, that the Canadian penny isn’t money, not even in using the frst three letters of their city’s name, ΑΘΕ, to Canada, where a few years ago they demonetized their signify: this is ours, we made this, and we stand behind it. -

Currency NOTES

BUREAU OF ENGRAVING AND PRINTING Currency NOTES www.moneyfactory.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS U.S. PAPER CURRENCY – AN OVERVIEW . 1 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM ............................. 1 CURRENCY TODAY ..................................... 2 Federal Reserve Notes. 2 PAST CURRENCY ISSUES ................................. 2 Valuation of Currency. 2 Demand Notes . 2 United States Notes. 3 Fractional Currency. 3 Gold Certificates . 4 The Gold Standard. 4 Silver Certificates. 4 Treasury (or Coin) Notes. 5 National Bank Notes. 5 Federal Reserve Bank Notes. 6 PAPER MONEY NOT ISSUED BY THE U.S. GOVERNMENT .............. 7 Celebrity Notes . 7 $3 Notes. 7 Confederate Currency . 7 Platinum Certificates. 7 INTERESTING AND FUN FACTS ABOUT U.S. PAPER CURRENCY . 9 SELECTION OF PORTRAITS APPEARING ON U.S. CURRENCY ............. 9 PORTRAITS AND VIGNETTES USED ON U.S. CURRENCY SINCE 1928 ..................................... 10 PORTRAITS AND VIGNETTES OF WOMEN ON U.S. CURRENCY ............ 10 AFRICAN-AMERICAN SIGNATURES ON U.S. CURRENCY ................ 10 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $2 NOTE ....................... 11 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $5 NOTE ....................... 11 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $10 NOTE ...................... 12 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $100 NOTE ..................... 12 ORIGIN OF THE $ SIGN .................................. 12 THE “GREEN” IN GREENBACKS ............................. 12 NATIONAL MOTTO “IN GOD WE TRUST” ........................ 13 THE GREAT SEAL OF THE UNITED STATES ....................... 13 Obverse Side of -

Symbols on U.S. Coins

U.S. MINT COIN CLASSROOM Symbols on U.S. Coins SOCIAL STUDIES 3-5 BIG QUESTION How are the coins we use today related to Roman coins from ancient times? TIMING 60 minutes SUMMARY: Students will learn about the evolution of coins by identifying features used in Roman times that have been carried into modern times. Then students will create their own Roman-inspired coin. LEARNING OBJECTIVES: • Students will learn about the evolution of coins and the different features we see today on coins such as symbols, inscriptions, and busts. • Students will create their own Roman-inspired coin, which will include a bust and symbols on the obverse and reverse, the edging, the mintmark, and the date. MATERIALS: • Ancient and Modern Coin worksheets • Books and webpages that provide ancient coin information and images, such as: o Roman History From Coins by Michael Grant o Handbook of Ancient Greek and Roman Coins by Zander Klawans o Numismatic Museum online collection: https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/numismatic-museum o American Numismatic Society collection: http://numismatics.org/search/results PROCEDURE: Discuss modern coins and introduce ancient coins (10 minutes) 1. Introduce the activity by displaying a penny (or project a large image of a penny) for the whole class to see. Ask your students what it is, and what we use it for. Explain to your students that if they look closer at coins, they will see that each one is a piece of artwork that tells us about a country's culture. 2. Ask students to describe what they see on the penny. -

Exonumia April 2017

Exonumia APRIL 2017 141 W. Johnstown Road, Gahanna, Ohio 43230 • (614) 414-0855 • [email protected] Introduction Welcome to Kolbe & Fanning’s first catalogue devoted to numismatic exonumia. Exonumia is broadly defined as tokens, medals, scrip and other numismatic items besides regularly issued coins and paper money. By “numismatic exonumia,” we refer to exonumia that pertains in some way to the coin collecting field. Examples might include tokens issued by coin dealers or collectors, medals depicting prominent collectors or scholars, badges produced for coin shows, “Good For” tokens or scrip issued by coin firms, and so on. Much of the material included in this catalogue was collected by our founder, George F. Kolbe, over the years. Some of it is very rare. Some of it is quite obscure. We think it is all very interesting and a lot of fun to boot, and we hope you agree. —Kolbe & Fanning Terms of Sale Items listed are available for immediate purchase at the prices indicated. No discounts are applicable. Items should be assumed to be one-of-a-kind and are subject to prior sale. Orders may be placed by post, email, phone or fax. Email is recommended, as orders will be filled on a first- come, first-served basis. Items will be sent via USPS insured mail unless alternate arrangements are made. The cost for delivery will be added to the invoice. There are no additional fees associated with purchases. Lots to be mailed to addresses outside the United States or its Territories will be sent only at the risk of the purchaser. -

John I Tzimiskes and the Invention of Class “A” Anonymous Folles Jeremy J

Piety and Propaganda: John I Tzimiskes and the Invention of Class “A” Anonymous Folles Jeremy J. Johnson For almost a century now, scholars have attributed the inven- this series run from 969 to 1092 AD, and although not really tion and decoration of Class “A” Anonymous Folles to the anonymous, these classes have been identified as such because piety of the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes (969-976 they represent the first examples of Byzantine coins to lack AD).1 Evidence for such a claim has come not only from the the traditional image and inscription relating them to a spe- ancient sources and archaeological record, but also from the cific emperor.3 decorative scheme of the coins themselves. With both the ob- Over the years, numismatists have attended to this unique verse and reverse of these coins solely dedicated to the name series of coins, specifically focusing their studies on those coins and image of Christ (Figure 1), it is no wonder that scholars of Class “A.”4 Unfortunately, however, most of the studies deal- think of these coins and the reasons behind their creation as ing with Class “A” coins have been, on the whole, numis- strictly religious in nature. However, in the examination of matic in nature. That is to say, in the words of Philip Grierson, the iconography of these coins and the social-historical events these studies have taken on the following format: surrounding John I Tzimiskes, it becomes rather apparent that The identification, classification, and de- the motive behind the issuing of these coins was not only one scription of individual coins, their attribu- of piety, but also one of propaganda.