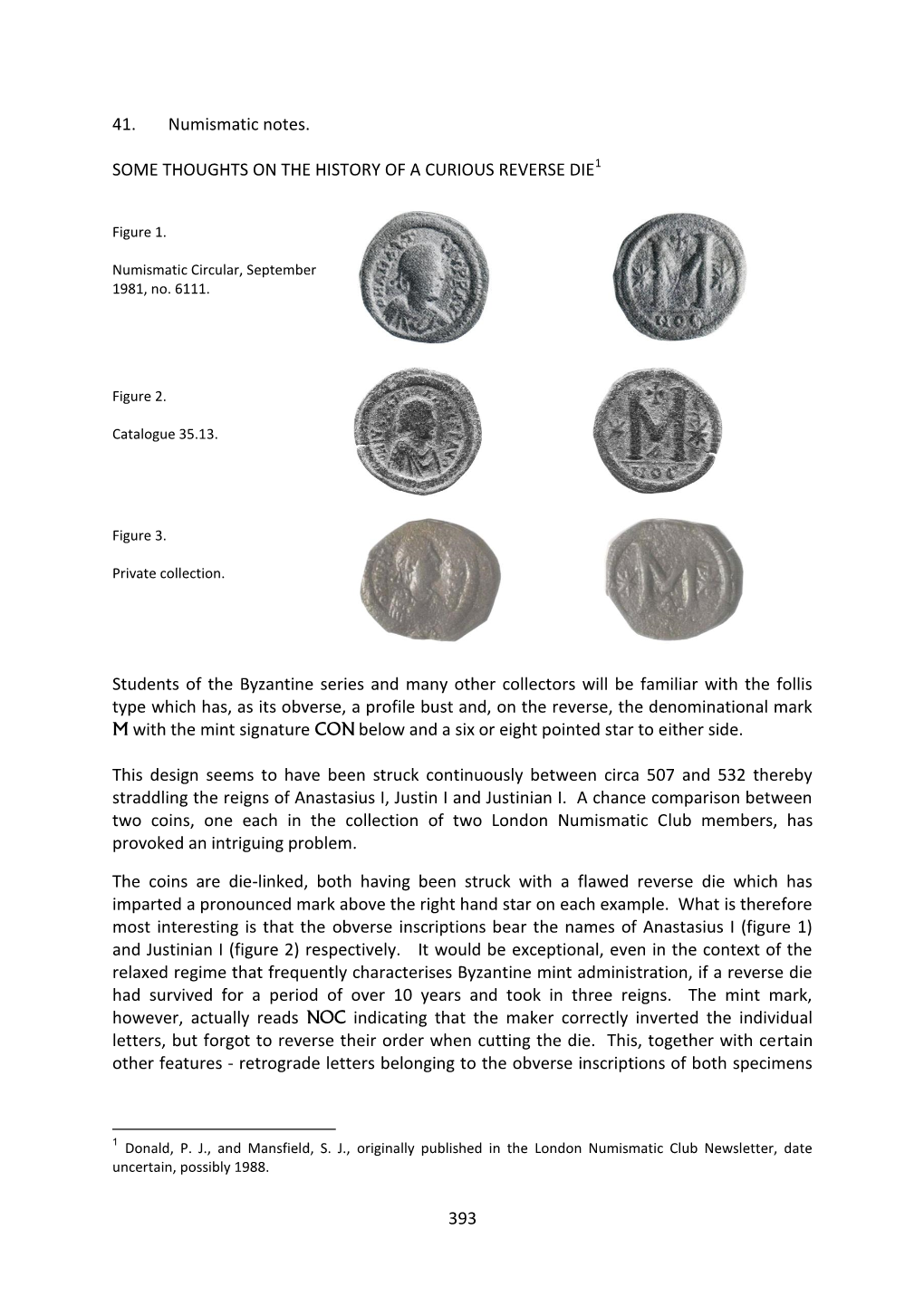

393 41. Numismatic Notes. SOME THOUGHTS on the HISTORY OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Byzantine Conquests in the East in the 10 Century

th Byzantine conquests in the East in the 10 century Campaigns of Nikephoros II Phocas and John Tzimiskes as were seen in the Byzantine sources Master thesis Filip Schneider s1006649 15. 6. 2018 Eternal Rome Supervisor: Prof. dr. Maaike van Berkel Master's programme in History Radboud Univerity Front page: Emperor Nikephoros II Phocas entering Constantinople in 963, an illustration from the Madrid Skylitzes. The illuminated manuscript of the work of John Skylitzes was created in the 12th century Sicily. Today it is located in the National Library of Spain in Madrid. Table of contents Introduction 5 Chapter 1 - Byzantine-Arab relations until 963 7 Byzantine-Arab relations in the pre-Islamic era 7 The advance of Islam 8 The Abbasid Caliphate 9 Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty 10 The development of Byzantine Empire under Macedonian dynasty 11 The land aristocracy 12 The Muslim world in the 9th and 10th century 14 The Hamdamids 15 The Fatimid Caliphate 16 Chapter 2 - Historiography 17 Leo the Deacon 18 Historiography in the Macedonian period 18 Leo the Deacon - biography 19 The History 21 John Skylitzes 24 11th century Byzantium 24 Historiography after Basil II 25 John Skylitzes - biography 26 Synopsis of Histories 27 Chapter 3 - Nikephoros II Phocas 29 Domestikos Nikephoros Phocas and the conquest of Crete 29 Conquest of Aleppo 31 Emperor Nikephoros II Phocas and conquest of Cilicia 33 Conquest of Cyprus 34 Bulgarian question 36 Campaign in Syria 37 Conquest of Antioch 39 Conclusion 40 Chapter 4 - John Tzimiskes 42 Bulgarian problem 42 Campaign in the East 43 A Crusade in the Holy Land? 45 The reasons behind Tzimiskes' eastern campaign 47 Conclusion 49 Conclusion 49 Bibliography 51 Introduction In the 10th century, the Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors coming from the Macedonian dynasty. -

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

ROTEX Gassolarunit Gas Condensing Boiler with Stratified Solar Storage Tank

For specialist technical operation ROTEX GasSolarUnit Gas condensing boiler with stratified solar storage tank Installation and maintenance instructions 0085 BM 0065 Type Rated thermal output GB ROTEX GSU 320 3 - 20 kW modulating Edition 09/2007 ROTEX GSU 520S 3 - 20 kW modulating ROTEX GSU 530S 7 - 30 kW modulating ROTEX GSU 535 8 - 35 kW modulating Manufacture number Customer Guarantee and conformity ROTEX accepts the guarantee for material and manufacturing defects according to this statement. Within the guarantee period, ROTEX agrees to have the device repaired by a person assigned by the company, free of charge. ROTEX reserves the right to replace the device. The guarantee is only valid if the device has been used properly and it can be proved that it was installed properly by an expert firm. As proof, we strongly recommend completing the enclosed installation and instruction forms and returning them to ROTEX. Guarantee period The guarantee period begins on the day of installation (billing date of the installation company), however at the latest 6 months after the date of manufacture (billing date). The guarantee period is not extended if the device is returned for repairs or if the device is replaced. Guarantee period of burner, boiler body and boiler electronics: 2 years Guarantee exclusion Improper use, intervention in the device and unprofessional modifications immediately invalidate the guarantee claim. Dispatch and transport damage are excluded from the guarantee offer. The guarantee explicitly excludes follow-up costs, especially the assembly and disassembly costs of the device. There is no guarantee claim for wear parts (according to the manufacturer's definition), such as lights, switches, fuses. -

Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg's Corpora Of

This is a repository copy of Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg’s Corpora of Nomismata. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/124522/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Jarrett, J orcid.org/0000-0002-0433-5233 (2018) Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg’s Corpora of Nomismata. Numismatic Chronicle, 177. pp. 514-535. ISSN 0078-2696 © 2017 The Author. This is an author produced version of a paper accepted for publication in Numismatic Chronicle. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ REVIEW ARTICLE Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg’s Corpora of Nomismata* JONATHAN JARRETT FRANZ FÜEG, Corpus of the Nomismata from Anastasius II to John I in Constantinople 713–976: Structure of the Issues; Corpus of Coin Finds; Contribution to the Iconographic and Monetary History, trans. -

The Developmentof Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrachs to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. The Development of Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrarchs to the Herakleian Dynasty General Introduction The emperor, as head of state, was the most important and powerful individual in the land; his official portraits and to a lesser extent those of the empress were depicted throughout the realm. His image occurred most frequently on small items issued by government officials such as coins, market weights, seals, imperial standards, medallions displayed beside new consuls, and even on the inkwells of public officials. As a sign of their loyalty, his portrait sometimes appeared on the patches sown on his supporters’ garments, embossed on their shields and armour or even embellishing their jewelry. Among more expensive forms of art, the emperor’s portrait appeared in illuminated manuscripts, mosaics, and wall paintings such as murals and donor portraits. Several types of statues bore his likeness, including those worshiped as part of the imperial cult, examples erected by public 1 officials, and individual or family groupings placed in buildings, gardens and even harbours at the emperor’s personal expense. -

The Coins and Banknotes of Denmark

The Coins and Banknotes of Denmark Danmarks Nationalbank's building in Copenhagen was designed by the internationally renowned Danish architect Arne Jacobsen and built between 1965-1978 The Coins and Banknotes of Denmark, 2nd edition, August 2005 Text may be copied from this publication provided that This edition closed for contributions in July 2005. Danmarks Nationalbank is specifically stated as the sour- Print: Fr. G. Knudtzon's Bogtrykkeri A/S ce. Changes to or misrepresentation of the content are ISBN 87-87251-55-8 not permitted. For further information about coins and (Online) ISBN 87-87251-56-6 banknotes, please contact: Danmarks Nationalbank, Information Desk Havnegade 5 DK-1093 Copenhagen K Telephone +45 33 63 70 00 (direct) or +45 33 63 63 63 E-mail [email protected] www.nationalbanken.dk 2 Old and new traditions s the central bank of Denmark, Danmarks There are many traditions linked to the appearan- ANationalbank has the sole right to produce ce of banknotes and coins, but the designs are also and issue Danish banknotes and coins. Subject to subject to ongoing renewal and development. For the approval of the Minister for Economic and Bus- instance, the Danish banknote series has been iness Affairs, Danmarks Nationalbank determines upgraded with new security features – holograms the appearance of Danish banknotes and coins and fluorescent colours. The coin series has been and their denominations. supplemented with a tower series and a fairy tale This brochure provides a brief description – in text series, the latter also in silver and gold editions. As and pictures – of the process from the artist's first a consequence of these changes, the time has sketch until the banknotes and coins are put into come to update this publication. -

Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2013 Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Custom Citation Kinney, Dale. "Spoliation in Medieval Rome." In Perspektiven der Spolienforschung: Spoliierung und Transposition. Ed. Stefan Altekamp, Carmen Marcks-Jacobs, and Peter Seiler. Boston: De Gruyter, 2013. 261-286. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/70 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Topoi Perspektiven der Spolienforschung 1 Berlin Studies of the Ancient World Spoliierung und Transposition Edited by Excellence Cluster Topoi Volume 15 Herausgegeben von Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler De Gruyter De Gruyter Dale Kinney Spoliation in Medieval Rome i% The study of spoliation, as opposed to spolia, is quite recent. Spoliation marks an endpoint, the termination of a buildlng's original form and purpose, whÿe archaeologists tradition- ally have been concerned with origins and with the reconstruction of ancient buildings in their pristine state. Afterlife was not of interest. Richard Krautheimer's pioneering chapters L.,,,, on the "inheritance" of ancient Rome in the middle ages are illustrated by nineteenth-cen- tury photographs, modem maps, and drawings from the late fifteenth through seventeenth centuries, all of which show spoliation as afalt accomplU Had he written the same work just a generation later, he might have included the brilliant graphics of Studio Inklink, which visualize spoliation not as a past event of indeterminate duration, but as a process with its own history and clearly delineated stages (Fig. -

Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation

Empire of Hope and Tragedy: Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Swain Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Timothy Gregory, Co-advisor Anthony Kaldellis Kristina Sessa, Co-advisor Copyright by Brian Swain 2014 Abstract This dissertation explores the intersection of political and ethnic conflict during the emperor Justinian’s wars of reconquest through the figure and texts of Jordanes, the earliest barbarian voice to survive antiquity. Jordanes was ethnically Gothic - and yet he also claimed a Roman identity. Writing from Constantinople in 551, he penned two Latin histories on the Gothic and Roman pasts respectively. Crucially, Jordanes wrote while Goths and Romans clashed in the imperial war to reclaim the Italian homeland that had been under Gothic rule since 493. That a Roman Goth wrote about Goths while Rome was at war with Goths is significant and has no analogue in the ancient record. I argue that it was precisely this conflict which prompted Jordanes’ historical inquiry. Jordanes, though, has long been considered a mere copyist, and seldom treated as an historian with ideas of his own. And the few scholars who have treated Jordanes as an original author have dampened the significance of his Gothicness by arguing that barbarian ethnicities were evanescent and subsumed by the gravity of a Roman political identity. They hold that Jordanes was simply a Roman who can tell us only about Roman things, and supported the Roman emperor in his war against the Goths. -

Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul Area Snelders, B

Identity and Christian-Muslim interaction : medieval art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area Snelders, B. Citation Snelders, B. (2010, September 1). Identity and Christian-Muslim interaction : medieval art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area. Peeters, Leuven. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15917 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15917 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 2. The Syrian Orthodox in their Historical and Artistic Settings 2.1 Northern Mesopotamia and Mosul The blossoming of ‘Syrian Orthodox art’ during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries is mainly attested for Northern Mesopotamia. At the time, Northern Mesopotamia was commonly known as the Jazira (Arabic for ‘island’), a geographic entity encompassing roughly the territory which is located between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, and lies north of Baghdad and south of Lake Van. 1 In ecclesiastical terms, this region is called Athur (Assyria). 2 Early Islamic historians and geographers distinguished three different districts: Diyar Mudar, Diyar Bakr, and Diyar Rabi cah. Today, these districts correspond more or less to eastern Syria, south-eastern Turkey, and northern Iraq, respectively. Mosul was the capital of the Diyar Rabi cah district, which ‘extended north from Takrit along both banks of the Tigris to the tributary Ba caynatha river a few kilometres north of Jazirat ibn cUmar (modern Cizre) and westwards along the southern slopes of the Tur cAbdin as far as the western limits of the Khabur Basin’. -

50 State Quarters Lesson Plans, Grades 9 Through 12

5: A World of Money Modern World History CLASS TIME Four 45- to 50-minute sessions OBJECTIVES Students will identify, recognize, and appreciate continuing global traditions related to the creation of national currencies. They will evaluate and analyze the role currency plays in shaping a national or regional identity. They will discuss and predict how regional, cultural, and national identity influences the designers of world currency. NATIONAL STANDARDS The standards used for these lesson plans reference the “10 Thematic Standards in Social Studies” developed by the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). • Culture—Students should be able to demonstrate the value of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups. Students should be able to construct reasoned judgments about specific cultural responses to persistent human issues. • Time, Continuity, and Change—Students should be able to investigate, interpret, and analyze multiple historical and contemporary viewpoints within and across cultures related to important events, recurring dilemmas, and persistent issues, while employing empathy, skepticism, and critical judgment. • Individual Development and Identity—Students should be able to articulate personal connections to time, place, and social and cultural systems. • Individuals, Groups, and Institutions—Students should be able to analyze group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture in both historical and contemporary settings. TERMS AND CONCEPTS: • The United States Mint 50 State Quarters® Program • Medium of exchange • Legal tender • Commemorative • Motto • Emblem • Symbolism • Nationalism • Patriotism • Circulating coin • Obverse (front) • Reverse (back) • Bust • Designer PORTIONS © 2004 U.S. MINT. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. 30 Grades 9 through 12 A World of Money SESSION 1 Materials • Chalkboard or whiteboard • Chalk or markers • Chart paper • Packets of U.S. -

Roman Empire Roman Empire

NON- FICTION UNABRIDGED Edward Gibbon THE Decline and Fall ––––––––––––– of the ––––––––––––– Roman Empire Read by David Timson Volum e I V CD 1 1 Chapter 37 10:00 2 Athanasius introduced into Rome... 10:06 3 Such rare and illustrious penitents were celebrated... 8:47 4 Pleasure and guilt are synonymous terms... 9:52 5 The lives of the primitive monks were consumed... 9:42 6 Among these heroes of the monastic life... 11:09 7 Their fiercer brethren, the formidable Visigoths... 10:35 8 The temper and understanding of the new proselytes... 8:33 Total time on CD 1: 78:49 CD 2 1 The passionate declarations of the Catholic... 9:40 2 VI. A new mode of conversion... 9:08 3 The example of fraud must excite suspicion... 9:14 4 His son and successor, Recared... 12:03 5 Chapter 38 10:07 6 The first exploit of Clovis was the defeat of Syagrius... 8:43 7 Till the thirtieth year of his age Clovis continued... 10:45 8 The kingdom of the Burgundians... 8:59 Total time on CD 2: 78:43 2 CD 3 1 A full chorus of perpetual psalmody... 11:18 2 Such is the empire of Fortune... 10:08 3 The Franks, or French, are the only people of Europe... 9:56 4 In the calm moments of legislation... 10:31 5 The silence of ancient and authentic testimony... 11:39 6 The general state and revolutions of France... 11:27 7 We are now qualified to despise the opposite... 13:38 Total time on CD 3: 78:42 CD 4 1 One of these legislative councils of Toledo..