Reading Disorders of Inattention and Hyperactivity: a Normalization Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Libraries

Public Libraries Alberta 403-948-0600 alderflatslibrary.ab.ca PUBLIC LIBRARIES [email protected] www.facebook.com/alderflatslibrary Alberta Public Library Services airdriepubliclibrary.ca National Library Symbol: AAF www.facebook.com/AirdriePublicLibrary Regional System: Yellowhead Regional Library #803, 10405 Jasper Ave. twitter.com/AirdrieLibrary Consortia Membership: The Regional Automation Consortium Edmonton, AB T5J 4R7 National Library Symbol: AAIM (TRAC) 780-427-4871 Regional System: Marigold Library System Founded in: 1973 Fax: 780-415-8594 Consortia Membership: The Regional Automation Consortium Hours: Th 7:00-9:00 [email protected] (TRAC) Services: www.alberta.ca/public-library-services.aspx Founded in: 1971 Internet Access Profile: The governing authority that enables the public library Hours: M, F, Sa 9:00-5:00; Tu-Th 11:00-7:00 Inter-Library Loan (ILL) boards to communicate & effectively manage public library Population Served: 61581 Computer training for first time users of computers - especially service with 7 library systems & over 200 municipal libraries. Note: The electronic acquisition budget is paid through the senior members Note: Part of the Corporate Strategic Services Division of library system. Personnel: Municipal Affairs. Services: Jean Sargeant, Chair Services: Remote Access Inter-Library Loan (ILL) Internet Access Alice B. Donahue Library & Archives Personnel: Electronic Media 4716 - 48th St. Diana Davidson, Director Inter-Library Loan (ILL) Athabasca, AB T9S 1R2 [email protected] Book -

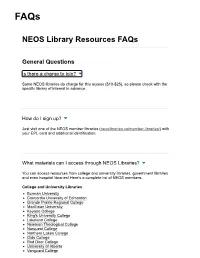

NEOS Library Resources Faqs

FAQs NEOS Library Resources FAQs General Questions Is there a charge to join? Some NEOS libraries do charge for this access ($10-$25), so please check with the specific library of interest in advance. How do I sign up? Just visit one of the NEOS member libraries (neoslibraries.ca/member-libraries/) with your EPL card and additional identification. What materials can I access through NEOS Libraries? You can access resources from college and university libraries, government libraries and even hospital libraries! Here's a complete list of NEOS members: College and University Libraries Burman University Concordia University of Edmonton Grande Prairie Regional College MacEwan University Keyano College King's University College Lakeland College Newman Theological College Norquest College Northern Lakes College Olds College Red Deer College University of Alberta Vanguard College Government Libraries Alberta Government Library Alberta Innovates - Technology Futures Hospital Libraries Alberta Health Services Covenant Health Please visit the NEOS Library Consortium Catalogue to learn more about the material available from the above libraries. Where should NEOS items be returned? You can return your NEOS materials to any NEOS affiliated library. You can find the list of libraries here: neoslibraries.ca/member-libraries/. Are there overdue fees? Yes. Overdue fees are $1.00 a day per item. What are the loan periods for NEOS library materials? The loan period is two weeks with four renewals as long as no one else has put a hold on the item, with a limit of 30 items on loan at a time. Powered by BiblioCommons. BiblioWeb: app05 Version 3.28.1 Last updated 2021/02/22 17:49. -

O Portal De Periódicos Da Capes: Estudo Sobre a Sua Evolução E Utilização

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA - UnB CENTRO DE DESENVOLVIMENTO SUSTENTÁVEL - CDS O Portal de Periódicos da Capes: estudo sobre a sua evolução e utilização. Elenara Chaves Edler de Almeida Brasília - DF 2006 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA - UnB CENTRO DE DESENVOLVIMENTO SUSTENTÁVEL - CDS O Portal de Periódicos da Capes: estudo sobre a sua evolução e utilização. Elenara Chaves Edler de Almeida Orientadora: Isabel Teresa Gama Alves Dissertação de Mestrado Brasília - DF 2006 Dedico este trabalho aos meus pais, Paulo Soares Edler e Wanzenir Chaves Edler ao meu marido, Jairo Lourenço de Almeida aos meus filhos, Laura e Pedro AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço à Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes) pela oportunidade de aperfeiçoamento. À Professora Isabel Teresa Gama Alves pela atenção, dedicação e orientação. Aos Professores Jorge Almeida Guimarães (Presidente da Capes) e José Fernandes de Lima (Diretor de Programas da Capes), pelo incentivo e estímulo. Aos colegas da Coordenação de Acesso à Informação Científica e Tecnológica/Capes que muito me auxiliaram. Aos professores, funcionários e colegas do Centro de Desenvolvimento Sustentável. A minha família, pelo apoio e paciência. A Deus, por dar-me força de chegar até o fim. RESUMO Este estudo buscou descrever e analisar o Programa de Apoio à Aquisição de Periódicos (PAAP) da Capes no período 2001-2005. Este programa se constitui no Portal de Periódicos e tem por objetivo: (a) apoiar as instituições de ensino superior com programas de pós- graduação stricto sensu na manutenção dos acervos de periódicos científicos internacionais, garantindo o acesso da comunidade acadêmica brasileira à produção científica e tecnológica mundial; e (b) democratizar o acesso à informação contribuindo para a diminuição das disparidades regionais, de modo a integrar a comunidade brasileira no cenário da produção científica mundial, e facilitar a inserção da produção científica brasileira no contexto da produção universal. -

Denise Erin Pasieka

A History of the Evolution of Nursing Research in the Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta from 1980 to 1998 by Denise Erin Pasieka A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Nursing Faculty of Nursing University of Alberta © Denise Erin Pasieka, 2017 ii Abstract The purpose of this study was to trace the historical evolution of nursing research at the Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta between 1980 and 1998. The questions that guided this study were: What were the trends in nursing research, specifically what type of questions were studied and what research methods were utilized by researchers between 1980 and 1998? What contextual factors, internal and external, influenced the development of nursing research? What roles did key leaders play to foster a climate conducive to research pursuits and in accessing/developing funding opportunities for nursing research? Historical methods were used to answer these questions. The primary data sources used in this study included eleven faculty produced scholarly reports on research and scholarly activities, which were supplemented with secondary data. In the reports there were 1180 listed publications (90 missing). This included 283 research- based articles, 118 non-research articles, 217 conference proceedings, 189 books/book chapters, and 221 editorials and other written work. The results showed the research production increased over time, that research topics shifted towards a clinical foci, that research methods became more sophisticated with an almost equal use of qualitative and quantitative methods by the late 1990s, that the majority of researchers in the Faculty of Nursing worked in research teams, and that there was a shift from publishing in minor nursing journals to major, international nursing journals over time. -

Comprehensive Institutional Plan 2015-2018

2015-2018 Comprehensive Institutional Plan Submitted to Alberta Innovation and Advanced Education June 1, 2015 2 Comprehensive Institutional Plan 2015‐2018 Comprehensive Institutional Plan Submitted to Alberta Innovation and Advanced Education June 1, 2015 4 Comprehensive Institutional Plan 2015‐2018 5 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 1 CONCORDIA’S GOALS, PRIORITIES, AND STRATEGIES......................................................... 4 2. ACCOUNTABILITY STATEMENT ........................................................................................ 5 AIAE OUTCOMES, MISSION, VISION AND ACADEMIC PLAN ............................................... 6 3. INSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT ................................................................................................ 7 3.1 AIAE OUTCOMES, BUSINESS PLAN, ROLES & MANDATES POLICY ....................... 7 3.2 MISSION ................................................................................................................ 7 3.3 VISION ................................................................................................................... 7 3.4 ACADEMIC PLAN DIRECTIONAL STATEMENTS ..................................................... 8 4. PLAN DEVELOPMENT .................................................................................................... 10 5. ENVIRONMENTAL SCAN ................................................................................................ 10 5.1 -

Ebook Collection Practices

EBOOK COLLECTION PRACTICES A Report to the Canadian Publishing Community on Trends, and Issues in Canada’s Public, University, and College Libraries Ken Roberts Carol Stephenson Thomas Guignard eBOUND Canada August 2015 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................... 1 • Public Libraries ........................................................................................... 1 • University Libraries ..................................................................................... 3 • College Libraries ........................................................................................ 3 • Major similarities among Public, Univeristy and College Libraries: ............... 4 INTRODUCTION AND PROJECT BACKGROUND .............................. 5 • Methodology .............................................................................................. 5 • About eBOUND Canada ............................................................................ 7 • Our Consultants ......................................................................................... 7 PUBLIC LIBRARIES ............................................................................. 9 • Background ............................................................................................... 9 • Public Library Core Information ................................................................ 10 2013 CULC Statistics .......................................................................... 11 Trends -

Public Libraries

Public Libraries Alberta 403-948-0600 780-388-3881 PUBLIC LIBRARIES Fax: 403-912-4002 www.facebook.com/alderflatslibrary Alberta Public Library Services [email protected] National Library Symbol: AAF www.airdriepubliclibrary.ca Regional System: Yellowhead Regional Library Standard Life Centre www.facebook.com/AirdriePublicLibrary Consortia Membership: The Regional Automation Consortium #803, 10405 Jasper Ave. twitter.com/AirdrieLibrary (TRAC) Edmonton, AB T5J 4R7 National Library Symbol: AAIM Founded in: 1973 780-427-4871 Regional System: Marigold Library System Hours: Tu 1:00-4:00; Th 7:00-9:00 Fax: 780-415-8594 Consortia Membership: The Regional Automation Consortium Services: [email protected] (TRAC) Internet Access www.alberta.ca/public-library-services-branch.aspx Founded in: 1971 Inter-Library Loan (ILL) Profile: The governing authority that enables the public library Hours: M-F 9:00-8:30; Sa 10:00-5:00; Su 1:00-5:00 Computer training for first time users of computers - especially boards to communicate & effectively manage public library Population Served: 61581 senior members service with 7 library systems & over 200 municipal libraries. Note: The electronic acquisition budget is paid through the Personnel: Note: Part of the Corporate Strategic Services Division of library system. Jean Sargeant, Chair Person Municipal Affairs. Services: Services: Remote Access Alice B. Donahue Library & Archives Inter-Library Loan (ILL) Internet Access 4716 - 48 St. Personnel: Electronic Media Athabasca, AB T9S 1R2 Diana Davidson, -

Institutional Self-Study

RED DEER COLLEGE INSTITUTIONAL SELF-STUDY Prepared for Campus Alberta Quality Council December 2019 COAT OF ARMS In 2004, a coat of arms incorporating a number of traditional symbols associated with Red Deer College, the Province of Alberta, or with learning was officially granted by the Canadian Heraldic Authority. Original concept by Dr. Darren S.A. George, assisted by the Heralds of the Canadian Heraldic Authority. MOTTO Ad Augustiora Per Eruditionem is a Latin phrase devised especially for the College. It means “To greater things through learning.” 2.1.7 Faculty Engagement in Governance 20 2.1.8 Faculty Involvement in Other Key Decision-making and Recommending Committees 21 CONTENTS 2.1.9 Future Academic Governance 21 2.2 Organizational Structure 22 2.2.1 RDC Organizational Structure 22 INTRODUCTION 6 2.2.2 Academic Portfolio Structure 24 2.2.3 The President and the President’s Land Acknowledgement 6 Executive Committee (PEC) 26 Context for the RDC Institutional Self-Study 6 2.2.4 School of Arts and Sciences Structure 27 Overview of the RDC Institutional Self-Study 7 2.2.5 School of Education Structure 28 Brief Overview of Red Deer College: 2.2.6 Additional Senior Administration Schools and Programs 7 with Degree Responsibility 29 Degrees Offered at Red Deer College 8 2.2.7 Terms and Conditions of Employment for Acknowledgements 9 Exempt Employees 29 2.2.8 Employee Code of Conduct 29 2.2.9 Dispute Resolution: Staff 29 CHAPTER 1 - RED DEER COLLEGE 10 2.2.10 Health and Safety 29 2.3 Improvement of Administration 30 1.1 Mandate and History -

Annual Report 2013–2014

Annual Report 2013–2014 Table of Contents Institutional Context 2 Accountability Statement 6 Management’s Responsibility for Reporting 7 Message from the Board Chair and the President 8 Board of Governors 2013–2014 9 A Year in Review 10 Reporting Our Results: Areas of Focus 14 Area of Focus 1: 15 Maximize college effectiveness, quality, and funding Area of Focus 2: 20 Rationalize college programs on the basis of workforce relevance or economic impact/contribution Area of Focus 3: 24 Build and leverage investor/partner relationships for the purpose of innovation Area of Focus 4: 29 Build a college brand consistent with a focus on workforce development, advancement, and customer value Area of Focus 5: 32 Align staffing and human resource strategies with the strategic plan, comprehensive institutional plan, and six areas of focus NorQuest Programs 2013–2014 35 Management Discussion and Analysis 36 Consolidated Financial Statements 39 ANNUAL REPORT 2013–2014 1 Institutional Context Vision Values NorQuest College is a vibrant, inclusive, and diverse learning We value people. We: environment that transforms lives • treat people with integrity and respect and strengthens communities. • empower and encourage risk taking • celebrate commitment, contribution, and accomplishments • promote health and wellness Mission We value learning. We: NorQuest College inspires lifelong • foster creativity, innovation, and critical thought learning and the achievement of • encourage growth, development, and lifelong learning career goals by offering relevant and accessible education. • build on the diversity of our learners, employees, and partners We value our role in the community. We: • display leadership and responsibility for our outcomes • partner to achieve community goals We value the quality of the processes we use in reaching our goals. -

Board Finance and Property Committee Motion and Final Document Summary

BOARD FINANCE AND PROPERTY COMMITTEE MOTION AND FINAL DOCUMENT SUMMARY The following Motions and Documents were considered by the Board Finance and Property Committee at its Tuesday, November 25, 2014 meeting: Agenda Title: University of Alberta 2015-16 Tuition Fee Proposal APPROVED MOTION: THAT the Board Finance and Property Committee, on the recommendation of the GFC Academic Planning Committee, recommend that the Board of Governors approve a proposal from the University Administration for a general tuition fee increase of 2.2%, effective September 1, 2015 and as illustrated in the table below. c a, b Change Undergraduate (Arts and Science) 2014-15 2015-16 $ % Domestic (Arts and Science) $5,320.80 $5,437.20 $116.40 2.2% Change c Domestic Graduate Fees a, b 2014-15 2015-16 $ % Course Based Masters $3,744.72 $3,826.80 $82.08 2.2% Thesis 919 d $2,335.92 $2,387.28 $ 51.36 2.2% Thesis Based (Masters and PhD) b, e $2,805.72 $2,867.40 $ 61.68 2.2% (a) Values are based on a full-time per term and full time per year. (b) Excludes applicable market modifier and/or program specific differential fees. (c) Tuition increases are applied to the fee index. As such, the effective year over year percentage change on the overall full-time program may be below 2.2 percent. (d) Tuition applies to thesis students who were admitted to the program of study prior to Fall 2011 and are assessed the reduced thesis rate. (e) Tuition applies to thesis students who were admitted to the program of study beginning in Fall 2011 or later; this is based on an annual fee assessment (including spring/summer). -

VOLUME 29, NO. 2 NEWSLETTER Fall 2006 ALBERTA ASSOCIATION

VOLUME 29, NO. 2 NEWSLETTER Fall 2006 ALBERTA ASSOCIATION OF COLLEGE LIBRARIANS ISSN 0829-4321 Published in May and November by the Association [email protected] http://aacl.engineseven.com/ Editor – Dave Weber able to positively link with other types of libraries in MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR the province. It was great to see everyone at the fall meeting of I hoped everyone enjoyed the festive season and AACL at Grant MacEwan College on November the New Year. rd 23 . A big thank you must go out to Karen Hering of GMC for planning and organizing the hosting In the spring, we can look forward to the end of the duties. Great lunch and good times. semester, blizzards accompanied by slightly warmer temperatures and the AACL meeting at I received a number of positive comments on this Mount Royal College on April 19th, 2007. fall’s workshop so I’d like to pass on this appreciation to Workshop Committee members Ann Geoff Owens Gish and Alice Swabey. I’m glad no one minded Mount Royal College the slight altering of the schedule due to the needs of those who had to venture home to points outside Alberta Association of College Librarians the city during this traditional Edmonton autumn Fall 2006 Minutes day. 6-313H of 106 St. Building I have noticed an increase in postings to our blog Grant MacEwan College since the meeting so I hope everyone becomes Thursday, November 23rd comfortable with visiting and sharing ideas. Thanks 9:00 am -3:00 pm to James Rout for all of his work on this great communication tool (http://aacl.engineseven.com).