The Solar System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHAPING the WIND of DYING STARS Noam Soker

Pleasantness Review* Department of Physics, Technion, Israel The role of jets in the common envelope evolution (CEE) and in the grazing envelope evolution (GEE) Cambridge 2016 Noam Soker •Dictionary translation of my name from Hebrew to English (real!): Noam = Pleasantness Soker = Review A short summary JETS See review accepted for publication by astro-ph in May 2016: Soker, N., 2016, arXiv: 160502672 A very short summary JFM See review accepted for publication by astro-ph in May 2016: Soker, N., 2016, arXiv: 160502672 A full summary • Jets are unavoidable when the companion enters the common envelope. They are most likely to continue as the secondary star enters the envelop, and operate under a negative feedback mechanism (the Jet Feedback Mechanism - JFM). • Jets: Can be launched outside and Secondary inside the envelope star RGB, AGB, Red Giant Massive giant primary star Jets Jets Jets: And on its surface Secondary star RGB, AGB, Red Giant Massive giant primary star Jets A full summary • Jets are unavoidable when the companion enters the common envelope. They are most likely to continue as the secondary star enters the envelop, and operate under a negative feedback mechanism (the Jet Feedback Mechanism - JFM). • When the jets mange to eject the envelope outside the orbit of the secondary star, the system avoids a common envelope evolution (CEE). This is the Grazing Envelope Evolution (GEE). Points to consider (P1) The JFM (jet feedback mechanism) is a negative feedback cycle. But there is a positive ingredient ! In the common envelope evolution (CEE) more mass is removed from zones outside the orbit. -

Perspective in Search of Planets and Life Around Other Stars

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 96, pp. 5353–5355, May 1999 Perspective In search of planets and life around other stars Jonathan I. Lunine* Reparto di Planetologia, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto di Astrofisica Spaziale, Rome I-00133, Italy The discovery of over a dozen low-mass companions to nearby stars has intensified scientific and public interest in a longer term search for habitable planets like our own. However, the nature of the detected companions, and in particular whether they resemble Jupiter in properties and origin, remains undetermined. The first detection of a planet orbiting around another star like Table 1. Jovian-mass planets around main-sequence stars our Sun came in 1995, after decades of null results and false Star’s Semi-major Period, alarms. As of this writing, 18 objects have been found with masses Star mass axis, AU days Eccentricity* Mass† potentially less than 12 times that of Jupiter, but none less than 40% of Jupiter’s mass, around main-sequence stars (1) (see Table HD187123 1.00 0.042 3.097 0.03 0.57 1). In addition, several planetary-mass bodies have been detected HD75289 1.05 0.046 3.5097 0.00 0.42 orbiting pulsars. Although these are interesting as well, the exotic Tau Boo 1.20 0.047 3.3126 0.00 3.66 environments around neutron stars make it unlikely that their 51 Peg 0.98 0.051 4.2308 0.01 0.44 companions are abodes for life. It is the success in finding planets Ups And 1.10 0.054 4.62 0.15 0.61 around Sun-like stars that provides a technological stepping stone HD217107 0.96 0.072 7.11 0.14 1.28 ‡ to one of the great aspirations of humanity: to find a world like 55 Cnc 0.90 0.110 14.656 0.04 1.5–3 the Earth orbiting around a distant star. -

Features in Cosmic-Ray Lepton Data Unveil the Properties of Nearby Cosmic Accelerators

Prepared for submission to JCAP Features in cosmic-ray lepton data unveil the properties of nearby cosmic accelerators O. Fornieri,a;b;d;1 D. Gaggerod and D. Grassob;c aDipartimento di Scienze Fisiche, della Terra e dell'Ambiente, Universit`adi Siena, Via Roma 56, 53100 Siena, Italy bINFN Sezione di Pisa, Polo Fibonacci, Largo B. Pontecorvo 3, 56127 Pisa, Italy cDipartimento di Fisica, Universit`adi Pisa, Polo Fibonacci, Largo B. Pontecorvo 3 dInstituto de F´ısicaTe´oricaUAM-CSIC, Campus de Cantoblanco, E-28049 Madrid, Spain E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. We present a comprehensive discussion about the origin of the features in the leptonic component of the cosmic-ray spectrum. Working in the framework of a up-to-date CR transport scenario tuned on the most recent AMS-02 and Voyager data, we show that the prominent features recently found in the positron and in the all-electron spectra by several experiments are compatible with a scenario in which pulsar wind nebulae (PWNe) are the dominant sources of the positron flux, and nearby supernova remnants (SNRs) shape the high-energy peak of the electron spectrum. In particular we argue that the drop-off in positron spectrum found by AMS-02 at 300 GeV can be explained | under different ∼ assumptions | in terms of a prominent PWN that provides the bulk of the observed positrons in the 100 GeV domain, on top of the contribution from a large number of older objects. ∼ Finally, we turn our attention to the spectral softening at 1 TeV in the all-lepton spectrum, ∼ recently reported by several experiments, showing that it requires the presence of a nearby arXiv:1907.03696v2 [astro-ph.HE] 6 Mar 2020 supernova remnant at its final stage. -

Supernova Environmental Impacts

Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union IAU Symposium No. 296 IAU Symposium IAU Symposium 7–11 January 2013 New telescopes spanning the full electromagnetic spectrum have enabled the study of supernovae (SNe) and supernova remnants 296 Raichak on Ganges, (SNRs) to advance at a breath-taking pace. Automated synoptic Calcutta, India surveys have increased the detection rate of supernovae by more than an order of magnitude and have led to the discovery of highly unusual supernovae. Observations of gamma-ray emission from 7–11 January 296 7–11 January 2013 Supernova SNRs with ground-based Cherenkov telescopes and the Fermi 2013 Supernova telescope have spawned new insights into particle acceleration in Raichak on Ganges, supernova shocks. Far-infrared observations from the Spitzer and Raichak Environmental Herschel observatories have told us much about the properties on Ganges, Calcutta, India Environmental and fate of dust grains in SNe and SNRs. Work with satellite-borne Calcutta, India Chandra and XMM-Newton telescopes and ground-based radio Impacts and optical telescopes reveal signatures of supernova interaction with their surrounding medium, their progenitor life history and of Impacts the ecosystems of their host galaxies. IAU Symposium 296 covers all these advances, focusing on the interactions of supernovae with their environments. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union Editor in Chief: Prof. Thierry Montmerle This series contains the proceedings of major scientifi c meetings held by the International Astronomical Union. Each volume contains a series of articles on a topic of current interest in Supernova astronomy, giving a timely overview of research in the fi eld. With contributions by leading scientists, these books are at a level Environmental Edited by suitable for research astronomers and graduate students. -

What Lies Immediately Outside of the Heliosphere in the Very Local Interstellar Medium (VLISM): What Will ISP Detect?

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 14, EPSC2020-68, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-68 Europlanet Science Congress 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. What lies immediately outside of the heliosphere in the very local interstellar medium (VLISM): What will ISP detect? Jeffrey Linsky1 and Seth Redfield2 1University of Colorado, JILA, Boulder CO, United States of America ([email protected]) 2Wesleyan University, Astronomy Department, Middletown CT, United States of America ([email protected]) The Interstellar Probe (ISP) will provide the first direct measurements of interstellar gas and dust when it travels far beyond the heliopause where the solar wind no longer influences the ambient medium. We summarize in this presentation what we have been learning about the VLISM from 20 years of remote observations with the high-resolution spectrographs on the Hubble Space Telescope. Radial velocity measurements of interstellar absorption lines seen in the lines of sight to nearby stars allow us to measure the kinematics of gas flows in the VLISM. We find that the heliosphere is passing through a cluster of warm partially ionized interstellar clouds. The heliosphere is now at the edge of the Local Interstellar Cloud (LIC) and heading in the direction of the slighly cooler G cloud. Two other warm clouds (Blue and Aql) are very close to the heliosphere. We find that there is a large region of the sky with very low neutral hydrogen column density, which we call the hydrogen hole. In the direction of the hydrogen hole is the brightest photoionizing source, the star Epsilon Canis Majoris (CMa). -

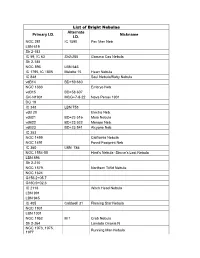

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Core-Collapse Supernovae Overview with Swift Collaboration

Publications Spring 2015 Core-Collapse Supernovae Overview with Swift Collaboration Kiranjyot Gill Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, [email protected] Michele Zanolin Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, [email protected] Marek Szczepańczyk Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/publication Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons, and the Physics Commons Scholarly Commons Citation Gill, K., Zanolin, M., & Szczepańczyk, M. (2015). Core-Collapse Supernovae Overview with Swift Collaboration. , (). Retrieved from https://commons.erau.edu/publication/3 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Core-Collapse Supernovae Overview with Swift Collaboration∗ Kiranjyot Gill,y Dr. Michele Zanolin,z and Marek Szczepanczykx Physics Department, Embry Riddle Aeronautical University (Dated: June 30, 2015) The Core-Collapse supernovae (CCSNe) mark the dynamic and explosive end of the lives of massive stars. The mysterious mechanism, primarily focused with the shock revival phase, behind CCSNe explosions could be explained by detecting the corresponding gravitational wave (GW) emissions by the laser interferometer gravitational wave observatory, LIGO. GWs are extremely hard to detect because they are weak signals in a floor of instrument noise. Optical observations of CCSNe are already used in coincidence with LIGO data, as a hint of the times where to search for the emission of GWs. More of these hints would be very helpful. For the first time in history a Harvard group has observed X-ray transients in coincidence with optical CCSNe. -

The Interstellar Medium

The Interstellar Medium http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/astropix.html THE INTERSTELLAR MEDIUM • Total mass ~ 5 to 10 x 109 solar masses of about 5 – 10% of the mass of the Milky Way Galaxy interior to the suns orbit • Average density overall about 0.5 atoms/cm3 or ~10-24 g cm-3, but large variations are seen • Composition - essentially the same as the surfaces of Population I stars, but the gas may be ionized, neutral, or in molecules (or dust) H I – neutral atomic hydrogen H2 - molecular hydrogen H II – ionized hydrogen He I – neutral helium Carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, dust, molecules, etc. THE INTERSTELLAR MEDIUM • Energy input – starlight (especially O and B), supernovae, cosmic rays • Cooling – line radiation and infrared radiation from dust • Largely concentrated (in our Galaxy) in the disk Evolution in the ISM of the Galaxy Stellar winds Planetary Nebulae Supernovae + Circulation Stellar burial ground The The Stars Interstellar Big Medium Galaxy Bang Formation White Dwarfs Neutron stars Black holes Star Formation As a result the ISM is continually stirred, heated, and cooled – a dynamic environment And its composition evolves: 0.02 Total fraction of heavy elements Total 10 billion Time years THE LOCAL BUBBLE http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/L/Local_Bubble.html The “Local Bubble” is a region of low density (~0.05 cm-3 and Loop I bubble high temperature (~106 K) 600 ly has been inflated by numerous supernova explosions. It is Galactic Center about 300 light years long and 300 ly peanut-shaped. Its smallest dimension is in the plane of the Milky Way Galaxy. -

Size and Scale Attendance Quiz II

Size and Scale Attendance Quiz II Are you here today? Here! (a) yes (b) no (c) are we still here? Today’s Topics • “How do we know?” exercise • Size and Scale • What is the Universe made of? • How big are these things? • How do they compare to each other? • How can we organize objects to make sense of them? What is the Universe made of? Stars • Stars make up the vast majority of the visible mass of the Universe • A star is a large, glowing ball of gas that generates heat and light through nuclear fusion • Our Sun is a star Planets • According to the IAU, a planet is an object that 1. orbits a star 2. has sufficient self-gravity to make it round 3. has a mass below the minimum mass to trigger nuclear fusion 4. has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit • A dwarf planet (such as Pluto) fulfills all these definitions except 4 • Planets shine by reflected light • Planets may be rocky, icy, or gaseous in composition. Moons, Asteroids, and Comets • Moons (or satellites) are objects that orbit a planet • An asteroid is a relatively small and rocky object that orbits a star • A comet is a relatively small and icy object that orbits a star Solar (Star) System • A solar (star) system consists of a star and all the material that orbits it, including its planets and their moons Star Clusters • Most stars are found in clusters; there are two main types • Open clusters consist of a few thousand stars and are young (1-10 million years old) • Globular clusters are denser collections of 10s-100s of thousand stars, and are older (10-14 billion years -

![Arxiv:1910.06396V4 [Physics.Pop-Ph] 12 Jun 2021 ∗ Rmtv Ieeitdi H R-Oa Eua(Vni H C System)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5215/arxiv-1910-06396v4-physics-pop-ph-12-jun-2021-rmtv-ieeitdi-h-r-oa-eua-vni-h-c-system-1105215.webp)

Arxiv:1910.06396V4 [Physics.Pop-Ph] 12 Jun 2021 ∗ Rmtv Ieeitdi H R-Oa Eua(Vni H C System)

Nebula-Relay Hypothesis: Primitive Life in Nebula and Origin of Life on Earth Lei Feng1,2, ∗ 1Key Laboratory of Dark Matter and Space Astronomy, Purple Mountain Observatory, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210023 2Joint Center for Particle, Nuclear Physics and Cosmology, Nanjing University – Purple Mountain Observatory, Nanjing 210093, China Abstract A modified version of panspermia theory, named Nebula-Relay hypothesis or local panspermia, is introduced to explain the origin of life on Earth. Primitive life, acting as the seeds of life on Earth, originated at pre-solar epoch through physicochemical processes and then filled in the pre- solar nebula after the death of pre-solar star. Then the history of life on the Earth can be divided into three epochs: the formation of primitive life in the pre-solar epoch; pre-solar nebula epoch; the formation of solar system and the Earth age of life. The main prediction of our model is that primitive life existed in the pre-solar nebula (even in the current nebulas) and the celestial body formed therein (i.e. solar system). arXiv:1910.06396v4 [physics.pop-ph] 12 Jun 2021 ∗Electronic address: [email protected] 1 I. INTRODUCTION Generally speaking, there are several types of models to interpret the origin of life on Earth. The two most persuasive and popular models are the abiogenesis [1, 2] and pansper- mia theory [3]. The modern version of abiogenesis is also known as chemical origin theory introduced by Oparin in the 1920s [1], and Haldane proposed a similar theory independently [2] at almost the same time. In this theory, the organic compounds are naturally produced from inorganic matters through physicochemical processes and then reassembled into much more complex living creatures. -

Atlas Menor Was Objects to Slowly Change Over Time

C h a r t Atlas Charts s O b by j Objects e c t Constellation s Objects by Number 64 Objects by Type 71 Objects by Name 76 Messier Objects 78 Caldwell Objects 81 Orion & Stars by Name 84 Lepus, circa , Brightest Stars 86 1720 , Closest Stars 87 Mythology 88 Bimonthly Sky Charts 92 Meteor Showers 105 Sun, Moon and Planets 106 Observing Considerations 113 Expanded Glossary 115 Th e 88 Constellations, plus 126 Chart Reference BACK PAGE Introduction he night sky was charted by western civilization a few thou - N 1,370 deep sky objects and 360 double stars (two stars—one sands years ago to bring order to the random splatter of stars, often orbits the other) plotted with observing information for T and in the hopes, as a piece of the puzzle, to help “understand” every object. the forces of nature. The stars and their constellations were imbued with N Inclusion of many “famous” celestial objects, even though the beliefs of those times, which have become mythology. they are beyond the reach of a 6 to 8-inch diameter telescope. The oldest known celestial atlas is in the book, Almagest , by N Expanded glossary to define and/or explain terms and Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian with Roman citizenship who lived concepts. in Alexandria from 90 to 160 AD. The Almagest is the earliest surviving astronomical treatise—a 600-page tome. The star charts are in tabular N Black stars on a white background, a preferred format for star form, by constellation, and the locations of the stars are described by charts. -

POVĚTROŇ Královéhradecký Astronomický Časopis ∗ Ročník 22 ∗ Číslo 3/2014 Slovo Úvodem

POVĚTROŇ Královéhradecký astronomický èasopis ∗ ročník 22 ∗ číslo 3/2014 Slovo úvodem. Zpoždění Povětroně 3/2014 lze vysvětlit dvěma slovy, slovem di- gitální a slovem planetárium. Jeho uvedení do provozu bylo chtě–nechtě prioritou číslo 1, jak o tom budeme psát v některém z následujících čísel. Nicméně, v tomto čísle jde zejména o dvojici èlánkù Milo¹e Boèka, které jsou věnovány superno- vám a jejich vizuálnímu pozorování. Dále Jaromír Ciesla pøipojuje vyhodnocení pravidelné ankety, a to dokonce za celý pùlrok. Miroslav Brož Obsah strana Milo¹ Boèek: Vizuálně pozorované supernovy v roce 2012 .............. 3 Milo¹ Boèek: Historicky pozorované i nepozorované supernovy v Galaxii . 14 Jaromír Ciesla: Sluneční hodiny druhého kvartálu roku 2014 . 17 Jaromír Ciesla: Sluneční hodiny tøetího kvartálu roku 2014 . 21 Titulní strana | Snímek supernovy SN 2012A z ledna 2012, pořízený na observatoøi Mount Lemmon SkyCenter Schulmanovým reflektorem (typu Ritchey{Chrétien) o průměru 0,81 m a CCD kamerou SBIG STX{16803. V pozadí na fotografii je vidno mnoho vzdálených gala- xií rùzných morfologických typù. c Adam Block, Mount Lemmon Skycenter, University of Arizona. K èlánku na str. 3. Povětroň 3/2014; Hradec Králové, 2014. Vydala: Astronomická spoleènost v Hradci Králové (7. 2. 2015 na 288. setkání ASHK) ve spolupráci s Hvězdárnou a planetáriem v Hradci Králové vydání 1., 24 stran, náklad 100 ks; dvouměsíčník, MK ÈR E 13366, ISSN 1213{659X Redakce: Miroslav Brož, Milo¹ Boèek, Martin Cholasta, Josef Kujal, Martin Lehký, Lenka Trojanová a Miroslav Ouhrabka Pøedplatné tištěné verze: vyøizuje redakce, cena 35,{ Kè za číslo (včetně po¹tovného) Adresa: ASHK, Národních mučedníků 256, Hradec Králové 8, 500 08; IÈO: 64810828 e{mail: [email protected], web: hhttp://www.ashk.czi Vizuálně pozorované supernovy v roce 2012 Milo¹ Boèek Někteří astrofyzikové uvádějí, že v pozorovatelné èásti vesmíru vybuchne a za- září jako supernovy až tøicet hvězd každou sekundu.1 V naší mateøské Galaxii bylo v¹ak dosud historicky zaznamenáno pouze sedm nebo osm takových vzplanutí (viz dodatkový èlánek).