T a O T E H K I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liber II - a Mensagem Do Mestre Therion

1 Liber II - A Mensagem do Mestre Therion Espaço Novo Æon www.thelema.com.br 2 Aleister Crowley A∴A∴ Publicação em Classe E. Espaço Novo Æon www.thelema.com.br 3 Liber II - A Mensagem do Mestre Therion LIBER II A MENSAGEM DO MESTRE THERIONi ii por Aleister Crowley “Faze o que tu queres deverá ser o todo da Lei” “Não há Lei além de Faze o que tu queres” “A palavra da Lei é Θελημα.” Θελημα —Thelema—significa Vontade. A Chave para esta Mensagem é esta palavra-Vontade. O primeiro significado óbvio desta Lei é confirmado pela antítese; “A palavra de Pecado é Restrição”. Novamente: “Tu não tens direito senão fazer tua vontade. Faze isso, e nenhum outro dirá não. Pois vontade pura, desaliviada de propósito, livre da sede de resultado, é toda senda perfeita.” Observe isto cuidadosamente; isso parece sugerir uma teoria de que se todo homem e toda mulher fizessem sua vontade—a verdadeira vontade—não haveria conflitos. “Todo homem e toda mulher é uma estrela”, e cada estrela se move por um caminho designado sem interferência. Há bastante espaço para todos; é apenas a desordem que cria confusão. A partir destas considerações deve ter ficado claro que “Faze o que tu queres” não significa “Faça o que você desejar”. Ela é a apoteose da Liberdade; mas é também o vínculo mais estrito possível. Faze o que tu queres — e então não faça nada mais. Não permita que nada desvie a ti daquela austera e santa tarefa. A Liberdade é absoluta para fazer a tua vontade; mas tente fazer qualquer outra coisa seja qual for, e instantaneamente os obstáculos vão surgir. -

LIBER ALEPH Vel CXI : the BOOK of WISDOM OR FOLLY

LIBER ALEPH VEL CXI THE BOOK OF WISDOM OR FOLLY in the Form of an Epistle of 666 THE GREAT WILD BEAST to his Son 777 being THE EQUINOX VOLUME III No. vi by THE MASTER THERION (Aleister Crowley) An LVII Sol in 0º 0’ 0” September 23 1961 e.v. 6:19 a.m. Liber Aleph - 2 A.·. A.·. Publication in Class B. Imprimatur N. Fra: A.·. A.·. O.M. 7 = 4 R.R. et A.C. Φ 6 = 5 Imperator Liber Aleph - 3 In Hastings (with little left but pipe and wit) Liber Aleph - 4 ENGLISH LIST OF CHAPTERS 1. APOLOGIA 2. ON THE QABALISTIC ART 3. ON CORRECTING ONE'S LIFE 4. FABLES OF LOVE 5. OF LOVE IN HISTORY 6. A FINAL THESIS ON LOVE 7. ON PERCEIVING ONE'S OWN NATURE 8. MORE ON THE WAY OF NATURE 9. HOW ONE SHOULD CONSIDER ONE'S NATURE 10. ON DREAMS (ACCIDENTAL) 11. ON DREAMS (NATURAL) 12. ON DREAMS (CLOTHED WITH HORROR) 13. ON DREAMS (CONTINUATION) 14. ON DREAMS (THE KEY) 15. ON ASTRAL TRAVEL 16. ON THELEMIC CULT 17. ON THE KEY OF DREAMS 18. ON THE SLEEP OF LIGHT 19. ON POISONS 20. ON THE MOTION OF LIFE 21. ON DISEASES OF THE BLOOD 22. ON THE WAY OF LOVE 23. ON THE MYSTICAL MARRIAGE 24. ON THE JOY OF SORROWS 25. ON THE ULTIMATE WILL 26. ON THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THINGS 27. ON THE HIDDEN WILL 28. ON THE SUPREME FORMULA 29. ON THE WAY OF INERTIA 30. ON THE WAY OP FREEDOM 31. -

Abrahadabra Encampment of O.T.O

418 the quarterly newsletter of Abrahadabra Encampment of O.T.O. Anno IV:xiv Sol 0° Aries, Luna What’s In a Name? 5° Sagittarius Dies Lunæ Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law. March 20, 2006 e.v. “Abrahadabra; the reward of Ra-Hoor-Khut.” Volume 1, Number 1 – Liber AL, III:1 IN THIS ISSUE In founding the first body of the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.) in the state of Maine, What’s In a Name? 1 we had the privilege and opportunity to name the body, and we discussed a number of Fr. Eparisteros, Master potential alternatives. We finally settled on Source of Light 2 Abrahadabra, so I thought it worth noting the by Fr. Azazel Alephomen meanings and connections associated with this Thelemic Texts 4 word and how they may relate to our work. by Fr. L.N.N. Abrahadabra is derivative of the word Stewardship 5 “abracadabra,” whose most commonly cited by Fr. Ash root is from the Aramaic avra kehdabra History of the Tarot 6 meaning, “I create as I speak.” The change in spelling is in recognition of the tenets of by Fr. Eparisteros Thelema by investing the name of the Egyptian Events Calendar 10 god Hadit/Had in the central position. This word is referenced three times in the third chapter of the Book of the Law, the chapter attributed unto the god of force and fire, Ra-Hoor-Khuit. Interestingly enough, it appears in both the Copyright © 2006 opening and the closing lines of that chapter, a significant position for such a magickal word of Abrahadabra Encampment, O.T.O., power. -

The Changing Role of Leah Hirsig in Aleister Crowley's Thelema, 1919

Aries – Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism 21 (2021) 69–93 ARIES brill.com/arie Proximal Authority The Changing Role of Leah Hirsig in Aleister Crowley’s Thelema, 1919–1930 Manon Hedenborg White Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden [email protected] Abstract In 1920, the Swiss-American music teacher and occultist Leah Hirsig (1883–1975) was appointed ‘Scarlet Woman’ by the British occultist Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), founder of the religion Thelema. In this role, Hirsig was Crowley’s right-hand woman during a formative period in the Thelemic movement, but her position shifted when Crowley found a new Scarlet Woman in 1924. Hirsig’s importance in Thelema gradually declined, and she distanced herself from the movement in the late 1920s. The article analyses Hirsig’s changing status in Thelema 1919–1930, proposing the term proximal authority as an auxiliary category to MaxWeber’s tripartite typology.Proximal authority is defined as authority ascribed to or enacted by a person based on their real or per- ceived relational closeness to a leader. The article briefly draws on two parallel cases so as to demonstrate the broader applicability of the term in highlighting how relational closeness to a leadership figure can entail considerable yet precarious power. Keywords Aleister Crowley – Leah Hirsig – Max Weber – proximal authority – Thelema 1 Introduction During the reign of Queen Anne of Great Britain (1665–1714), Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough (1660–1744), was the second most powerful woman in the kingdom. As the queen’s favourite, the Duchess overcame many restrictions hampering women of the time. -

The Star Ruby Is the Basic Thelemic Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram

The Star Ruby is the basic Thelemic banishing ritual of the pentagram. The number of the Liber, XXV, is the square of five, and the Pentagram has the red color of Geburah. It is the first official ritual learned by the Probationer to the A.’.A.’.. In contrast to its antecedent the ‘Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram’, it is designed to elevate the Aspirant’s consciousness to the Solar-Phallic energy of the Aeon of Horus. The first step in this effort is to equilibrate the positive and negative energies of the four quarters, which are no longer centered upon the earth but upon Sol, which is also the core of each of our individual natures. The attribution of the Elements to the Four Directions corresponds to the element of the four Cherubs in its antecedent rite and the corresponding fixed signs of the Zodiac. This is primarily an earth-based perspective suitable for the Probationer of the A.’.A.’.. Also, as a ritual of the Aeon of Horus, the Star Ruby stands between the LBR and the Ritual of the Mark of the Beast, Liber V vel Reguli. Just as the former set down the basic format for the Star Ruby, so the latter can be used to interpret some of the symbols and directions. Frater A.L. (1983) provides some important background for this ritual. He reports the first version as being written no later than 1913, when the Book of Lies was first published, and that this modified Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram was modified during the Cephalu period (1920’s). -

Gnosticism, Transformation, and the Role of the Feminine in the Gnostic Mass of the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (E.G.C.) Ellen P

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-13-2014 Gnosticism, Transformation, and the Role of the Feminine in the Gnostic Mass of the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (E.G.C.) Ellen P. Randolph Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14110766 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Randolph, Ellen P., "Gnosticism, Transformation, and the Role of the Feminine in the Gnostic Mass of the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (E.G.C.)" (2014). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1686. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1686 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida GNOSTICISM, TRANSFORMATION, AND THE ROLE OF THE FEMININE IN THE GNOSTIC MASS OF THE ECCLESIA GNOSTICA CATHOLICA (E.G.C.) A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Ellen P. Randolph 2014 To: Interim Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Ellen P. Randolph, and entitled Gnosticism, Transformation, and the Role of the Feminine in the Gnostic Mass of the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (E.G.C.), having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

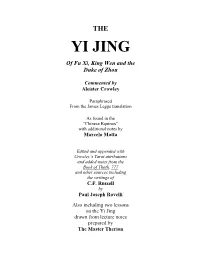

YI JING of Fu Xi, King Wen and the Duke of Zhou

THE YI JING Of Fu Xi, King Wen and the Duke of Zhou Commented by Aleister Crowley Paraphrased From the James Legge translation As found in the “Chinese Equinox” with additional notes by Marcelo Motta Edited and appended with Crowley‟s Tarot attributions and added notes from the Book of Thoth, 777 and other sources including the writings of C.F. Russell by Paul Joseph Rovelli Also including two lessons on the Yi Jing drawn from lecture notes prepared by The Master Therion A.‟.A.‟. Publication in Class B Imprimatur N. Frater A.‟.A.‟. All comments in Class C EDITORIAL NOTE By Marcelo Motta Our acquaintance with the Yi Jing dates from first finding it mentioned in Book Four Part III, the section on Divination, where A.C. expresses a clear preference for it over other systems as being more flexible, therefore more complete. We bought the Richard Wilhelm translation, with its shallow Jung introduction, but never liked it much. Eventually, on a visit to Mr. Germer, he showed us his James Legge edition, to which he had lovingly attached typewritten reproductions of A.C.‟s commentaries to the Hexagrams. We requested his permission to copy the commentaries. Presently we obtained the Legge edition and found that, although not as flamboyant as Wilhelm‟s, it somehow spoke more clearly to us. We carefully glued A.C.‟s notes to it, in faithful copy of our Instructor‟s device. To this day we have the book, whence we have transcribed the notes for the benefit of our readers. Mr. Germer always cast the Yi before making what he considered an important decision. -

Babalon Rising: Jack Parsons’ Witchcraft Prophecy

Babalon Rising: JaCk parsons’ WitChCraFt propheCy Erik Davis In the forty yearS or so following the death of John Whiteside Parsons in 1952, his name—Jack Parsons from here on out—circulated principally among magic folk, critics of Scientology, and historians of modern rock- etry. In the new century, however, the tale of the SoCal rocket scientist- cum-sex magician has proven a hot commodity, told and retold in a series of articles, biographies, graphic novels, movie scripts, and reality tv shows that have transformed Parsons into one of the most storied figures in the history of American occulture. The superficial reasons are easy to see: with its charismatic blend of sex, sorcery, technology and death, Parsons’ story haunts a dark crossroads of the Southern California mindscape, scrawling a prophetic glyph in the wet pavement of postwar America. Indeed, his tale is so outrageous that if it did not exist, it would need—as they say—to be invented. But if it were invented—that is, if his life were presented as the fiction it in so many ways resembles—it would be hard to believe, even as a fiction. The narrative would seem overly contrived, at once too pulp and too poetic, too rich with allegorical synchronicity to stage the necessary suspension of disbelief. In this essay, I want to explore an unremarked aspect of Jack Parsons’ life and thought, what I will call his magickal feminism. In his 1946 text Free- 165 166 Erik Davis dom is a Two-Edged Sword, Parsons issued a call for women to take up the spiritual, sexual, and political sword—a cry for female autonomy that also eerily anticipated the militant witchcraft that would find historical expres- sion in California over twenty years later. -

Contents from the Grand Master

Agapé is the Offi cial Organ Volume IX, Number 2 of the U. S. Grand Lodge of q ns E • R ns l • A IV: Ordo Templi Orientis A August 1, 2007 From the Grand Master Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. Annual Report 5. To broaden the scope of initiator training as appropriate. One of the goals of the U.S.G.L. Strategic Plan was to increase 6. Coordinate when necessary with S.G.I.G.s, C.I.T.s, member knowledge of Grand Lodge activities by publishing the Grand Treasurer General and the Initiation an annual report. Our annual report for the 2006-2007 fi scal Secretary. year (Anno IVxiv) has been completed, and is now available at: These workshops (or personal training by an S.G.I.G. or C.I.T.) are now required for those who wish to apply for an initiation oto-usa.org/usgl_annual_report_IVxiv.pdf charter. They are also excellent for review, and I encourage all chartered initiators as well as aspiring initiators and local Initiator Training initiation team members (of III° and up) to a end these workshops whenever possible. Keep an eye on the U.S.G.L. We have formally created an offi ce of Initiator Training website for updates on the workshop schedule. Coordinator, and have appointed Sister Kim Knight to same. The duties of this offi ce are: Dispute Resolution 1. To coordinate and promote Initiator Training Book 194 states that the Grand Tribunal “decides all disputes Workshops. and complaints which have not been composed by the Chapters 2. -

LETTER to a BRAZILIAN MASON UNEXPURGATED Marcelo Ramos Motta

LETTER TO A BRAZILIAN MASON UNEXPURGATED Marcelo Ramos Motta Rio de Janeiro, 9 July 1963 e.v. Dear Dr.G.: Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. I read with pleasure in the news that Brazilian Masonry has finally decided to take once more an active role in the affairs of this nation. I remembered then my conversation with you, and our parting, when you remarked that in your opinion the Roman Church was a good introduction to adult life for children. I told you then: "Perhaps, but Masonry is infinitely better"; and I take this opportunity to repeat and enlarge that statement. I did not wish at the time to discuss the validity or lack of validity of the Roman Church as a training ground for children. One cannot discuss this subject. It is a subject that must - I repeat, must - be researched by every responsible individual, particularly a high grade Mason, and particularly in Brazil, where that church had so much influence in the psychological makeup of the people - with the results that we see at present. For such a research, vitally important at this point, a careful analysis of evidence scattered in the works of many impartial and reputable observers is essential - an analysis that cannot be made in a conversation or summed up in an argument. I know the facts; you did not, at the time; assertions by me, though based on facts, would have seemed to you biased and unfair; the more so because you, naturally, suspect me and my intentions - Thelemites are not better liked or trusted at present than the Gnostics and Essenes were in their day. -

SEX MAGICK R 5

Unlock the Secrets of the Universe The Equinox, in print from 1909–1919, was a magical journal published by Aleister Crowley and included Crowley’s own A...A... laws, rituals and rites, reviews, and magical works by other important SEX MAGICK practitioners. Published as ten volumes, much of the material remains out of print today. Now, for the first time since Israel Regardie’s selections Gems from the Equinox (1974) renowned scholar and U.S. Deputy Grandmaster General of the O.T.O. Lon Milo DuQuette presents readers with his own selections from this classic publication, The Best of the Equinox. Volume III of the series presents perhaps the most titillating of esoteric subjects, Sex Magick. Once he grasped the fundamentals of sexual magick, Aleister Crowley understood it to be the key that unlocks the secrets of the universe. He dedicated the entire second half of his life to exploring its mysteries. This volume presents the bulk of Crowley’s written works on the subject and includes The Gnostic Mass, Energized Enthusiasm, Liber A’ash, Liber Chath, and Liber Stellae Rubeae. VOLUME III THE BEST OF THE EQUINOX ABOUT THE AUTHORS r Aleister Crowley (1875–1947) poet, mountaineer, secret agent, magus, CROWLEY libertine, and prophet was dubbed by the tabloids, “The Wickedest Man in the World.” SEX Lon Milo DuQuette is a bestselling author and lecturer whose books on Magick, Tarot, and the Western Mystery Traditions have been translated MAGICK into ten languages. He lives in Costa Mesa, CA with his beautiful wife Constance. ISBN: 978-1-57863-571-9 U.S. -

Liber Samekh

MAGICK IN THEORY AND PRACTICE [BOOK 4 (LIBER ABA) PART III] First published Paris: Lecram Press., 1930 Corrected edition included in Magick: Book 4 Parts I-IV, York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1994 This electronic edition prepared and issued by Celephaïs Press, somewhere beyond the Tanarian Hills, and manifested in the waking world in Leeds, Yorkshire, England July 2004. (c) Ordo Templi Orientis JAF Box 7666 New York NY 10116 U.S.A. MAGICK IN THEORY AND PRACTICE BY THE MASTER THERION (ALEISTER CROWLEY) BOOK 4 PART III Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. Celephaïs Press Ulthar - Sarkomand - Inquanok – Leeds 2004 Hymn to Pan [v] ——— ἔφιξ᾿ἔρωτι περιαρχὴς δ᾿ ἀνεπιόµαν ἰὼ ἰὼ πὰν πὰν ὢ πὰν πὰν ἁ λιπλαγκτε, κυλλανίας χιονοκτύποι πετραίς ἀπὸ δειράδος φάνηθ᾿, ὦ θεῶν χοροπόι ἄναξ —SOPH. Aj. ——— THRILL with lissome lust of the light, O man! My man! Come careering out of the night Of Pan! Io Pan! Io Pan! Io Pan! Come over the sea From Sicily and from Arcady! Roaming as Bacchus, with fauns and pards And nymphs and satyrs for thy guards, On a milk-white ass, come over the sea To me, to me, Come with Apollo in bridal dress (Shepherdess and pythoness) Come with Artemis, silken shod, And wash thy white thigh, beautiful God, In the moon of the woods, on the marble mount, The dimpled dawn of the amber fount! Dip the purple of passionate prayer In the crimson shrine, the scarlet snare, The soul that startles in eyes of blue To watch thy wantonness weeping through [vi] — v — HYMN TO PAN The tangled grove, the gnarléd bole Of the living tree that is spirit and soul And body and brain - come over the sea, (Io Pan! Io Pan!) Devil or god, to me, to me, My man! my man! Come with trumpets sounding shrill Over the hill! Come with drums low muttering From the spring! Come with flute and come with pipe! Am I not ripe? I, who wait and writhe and wrestle With air that hath no boughs to nestle My body, weary of empty clasp, Strong as a lion and sharp as an asp - Come, O come! I am numb With the lonely lust of devildom.