Pulling the Plug on the Electric Chair: the Unconstitutionality of Electrocution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Status of Capital Punishment: a World Perspective

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 56 Article 1 Issue 4 December Winter 1965 The tS atus of Capital Punishment: A World Perspective Clarence H. Patrick Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Clarence H. Patrick, The tS atus of Capital Punishment: A World Perspective, 56 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 397 (1965) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. The Journal of CRIMINAL LAW, CRIMINOLOGY, AND POLICE SCIENCE Copyright @ by Northwestern University School of Law VOL 56 DECEMBER 1965 NO. 4 THE STATUS OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: A WORLD PERSPECTIVE CLARENCE H. PATRICK The author has been professor of sociology at Wake Forest College since 1947. Earlier he was pro- fessor of sociology at Shorter College and Meredith College. He received the A.B. degree from Wake Forest College and the Ph.D. degree from Duke University. He is the author of Alcohol, Culture,and Society, and of articles in the fields of criminology and race relations. From 1953-1956 he was chairman of the North Carolina Board of Paroles. He has been a member of the North Carolina Pro- bation Commission since 1957 and is presently Chairman of the Commission. The death penalty is one of the most ancient of tested which would explain some of those differ- all methods of punishments. -

Read Our Full Report, Death in Florida, Now

USA DEATH IN FLORIDA GOVERNOR REMOVES PROSECUTOR FOR NOT SEEKING DEATH SENTENCES; FIRST EXECUTION IN 18 MONTHS LOOMS Amnesty International Publications First published on 21 August 2017 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2017 Index: AMR 51/6736/2017 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 3 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations Table of Contents Summary ..................................................................................................................... 1 ‘Bold, positive change’ not allowed ................................................................................ -

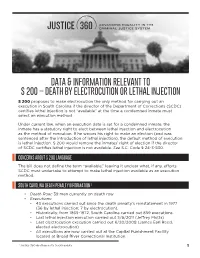

Death by Electrocution Or Lethal Injection

DATA & INFORMATION RELEVANT TO S 200 – DEATH BY ELECTROCUTION OR LETHAL INJECTION S 200 proposes to make electrocution the only method for carrying out an execution in South Carolina if the director of the Department of Corrections (SCDC) certifies lethal injection is not “available” at the time a condemned inmate must select an execution method. Under current law, when an execution date is set for a condemned inmate, the inmate has a statutory right to elect between lethal injection and electrocution as the method of execution. If he waives his right to make an election (and was sentenced after the introduction of lethal injection), the default method of execution is lethal injection. S 200 would remove the inmates’ right of election if the director of SCDC certifies lethal injection is not available. See S.C. Code § 24-3-530. CONCERNS ABOUT S 200 LANGUAGE The bill does not define the term “available,” leaving it unclear what, if any, efforts SCDC must undertake to attempt to make lethal injection available as an execution method. SOUTH CAROLINA DEATH PENALTY INFORMATION 1 • Death Row: 39 men currently on death row • Executions: • 43 executions carried out since the death penalty’s reinstatement in 1977 (36 by lethal injection; 7 by electrocution). • Historically, from 1865–1972, South Carolina carried out 859 executions. • Last lethal injection execution carried out 5/6/2011 (Jeffrey Motts) • Last electrocution execution carried out 6/20/2008 (James Earl Reed, elected electrocution) • All executions are now carried out at the Capital Punishment Facility located at Broad River Correctional Institution. 1 Justice 360 death penalty tracking data. -

Death by Garrote Waiting in Line at the Security Checkpoint Before Entering

Death by Garrote Waiting in line at the security checkpoint before entering Malacañang, I joined Metrobank Foundation director Chito Sobrepeña and Retired Justice Rodolfo Palattao of the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan who were discussing how to inspire the faculty of the Unibersidad de Manila (formerly City College of Manila) to become outstanding teachers. Ascending the grand staircase leading to the ceremonial hall, I told Justice Palattao that Manuel Quezon never signed a death sentence sent him by the courts because of a story associated with these historic steps. Quezon heard that in December 1896 Jose Rizal's mother climbed these steps on her knees to see the governor-general and plead for her son's life. Teodora Alonso's appeal was ignored and Rizal was executed in Bagumbayan. At the top of the stairs, Justice Palattao said "Kinilabutan naman ako sa kinuwento mo (I had goosebumps listening to your story)." Thus overwhelmed, he missed Juan Luna's Pacto de Sangre, so I asked "Ilan po ang binitay ninyo? (How many people did you sentence to death?)" "Tatlo lang (Only three)", he replied. At that point we were reminded of retired Sandiganbayan Justice Manuel Pamaran who had the fearful reputation as The Hanging Judge. All these morbid thoughts on a cheerful morning came from the morbid historical relics I have been contemplating recently: a piece of black cloth cut from the coat of Rizal wore to his execution, a chipped piece of Rizal's backbone displayed in Fort Santiago that shows where the fatal bullet hit him, a photograph of Ninoy Aquino's bloodstained shirt taken in 1983, the noose used to hand General Yamashita recently found in the bodega of the National Museum. -

Vir an Emasculation of the 'Perfect Sodomy' Or Perceptions of 'Manliness' in the Harbours of Andalusia and Colonial Mexico City, 1560-1699

Vir An emasculation of the 'perfect sodomy' or perceptions of 'manliness' in the harbours of Andalusia and colonial Mexico City, 1560-1699 Federico Garza Carvajal Center for Latin American Research and Documentation University of Amsterdam "Prepared for delivery at the 1998 meeting of the Latin American Studies Association, The Palmer House Hilton Hotel, Chicago, Illinois, September 24-26, 1998" Vir An emasculation of the 'perfect sodomy' or perceptions of 'manliness' in the harbours of Andalusia and colonial Mexico City, 1560-1699 Federico Garza Carvajal 2 1 In 1698, Magistrate Villaran, pronounced both Bartholome, a twenty-six year old sailor from Sicily, and Giovanni Mule, a native of Palermo, guilty of having committed the "nefarious sin of sodomy" aboard Nuestra Senora del Carmen, an Admiral's ship docked in the harbour of Cadiz awaiting to set sail for the Indies in the Americas. The Magistrate condemned Bartholome "to death by fire in the accustomed manner and Juan Mule to public humiliation," or rather, "taken and placed within sight of the execution scaffold then passed over the flames and [thereafter] banished permanently from this Kingdom."1 Three years later, after a lengthy appeal process, "Bartholome Varres Cavallero with minute difference came out of the prison mounted on an old beast of burthen, dressed in a white tunic and hood, his feet and hands tied." About his neck hung a crucifix of God our Lord." The young boy, about the age of fourteen years, who the Spaniards rebaptized as "Juan Mule, nude from the waist upward, his hands and feet also tied, rode on a young beast of burthen" just behind Bartholome. -

Death Penalty & Genocide SWRK4007

Death Penalty & Genocide SWRK4007 Dr. Anupam Kumar Verma Assistant Professor Dept. of Social Work MGCUB, Bihar DEATH PENALTY Capital punishment Death Penalty, also known as the Capital Punishment, is a government sanctioned practice whereby a person is put to death by the state as a punishment for a crime. Death penalty or Capital Punishment is a legal process wherein a person is put to death by a state in accordance to a crime committed. Crimes that are punishable by Death are known as capital crimes or capital offences, and commonly include offences such as Murder, Treason, War crimes, Crimes against humanity and Genocide. Capital punishment has been used over the years by almost every society in order to punish the guilty for some particular crimes such as punishment for premeditated murder, espionage (Secret) , treason etc. In some countries sexual crimes such as Rape, or related activities carry the death penalty, so does Religious Crimes such as Apostasy (the formal renunciation of the State religion). Worldwide only 58 nations (Iran, United States, Egypt, Nigeria including India) are actively practicing capital punishment, whereas 95 countries(France, South Korea, Alska, Ghana, Ireland) have abolished the use of capital punishment Types of Death Penalty: In Ancient History– Crushing by Elephant, Blood Eagle, Boiling to Death, Stoning, Garrote. - Crucifixion -Lethal injection (2001) - Hanging to till Death - Electric chair(1926) -Gas -Firing squad Cases & Statement: In the Judgment of ‘Bachan Singh v/s State of Punjab (1980)2SCJ475’, 1980, the Supreme Court ruled that death penalty should only be used in the ‘Rarest of Rare’ cases, but does not give a definition as to what ‘Rarest of Rare’ means. -

Execution Ritual : Media Representations of Execution and the Social Construction of Public Opinion Regarding the Death Penalty

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2011 Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty. Emilie Dyer 1987- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Dyer, Emilie 1987-, "Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 388. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/388 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXECUTION RITUAL: MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fullfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May, 2011 -------------------------------------------------------------- EXECUTION RITUAL : MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Brook Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Approved on April 11, 2011 by the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director (Dr. -

Sounding the Last Mile: Music and Capital Punishment in the United States Since 1976

SOUNDING THE LAST MILE: MUSIC AND CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE UNITED STATES SINCE 1976 BY MICHAEL SILETTI DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Jeffrey Magee, Chair and Director of Research Professor Gayle Magee Professor Donna A. Buchanan Associate Professor Christina Bashford ABSTRACT Since the United States Supreme Court reaffirmed the legality of the death penalty in 1976, capital punishment has drastically waxed and waned in both implementation and popularity throughout much of the country. While studying opinion polls, quantitative data, and legislation can help make sense of this phenomenon, careful attention to the death penalty’s embeddedness in cultural, creative, and expressive discourses is needed to more fully understand its unique position in American history and social life. The first known scholarly study to do so, this dissertation examines how music and sound have responded to and helped shape shifting public attitudes toward capital punishment during this time. From a public square in Chicago to a prison in Georgia, many people have used their ears to understand, administer, and debate both actual and fictitious scenarios pertaining to the use of capital punishment in the United States. Across historical case studies, detailed analyses of depictions of the death penalty in popular music and in film, and acoustemological research centered on recordings of actual executions, this dissertation has two principal objectives. First, it aims to uncover what music and sound can teach us about the past, present, and future of the death penalty. -

The Chair, the Needle, and the Damage Done: What the Electric Chair and the Rebirth of the Method-Of-Execution Challenge Could M

Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy Volume 15 Article 5 Issue 1 Fall 2005 The hC air, the Needle, and the Damage Done: What the Electric Chair and the Rebirth of the Method-of-Execution Challenge Could Mean for the Future of the Eighth Amendment Timothy S. Kearns Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cjlpp Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kearns, Timothy S. (2005) "The hC air, the Needle, and the Damage Done: What the Electric Chair and the Rebirth of the Method-of- Execution Challenge Could Mean for the Future of the Eighth Amendment," Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy: Vol. 15: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cjlpp/vol15/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHAIR, THE NEEDLE, AND THE DAMAGE DONE: WHAT THE ELECTRIC CHAIR AND THE REBIRTH OF THE METHOD-OF-EXECUTION CHALLENGE COULD MEAN FOR THE FUTURE OF THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT Timothy S. Kearnst INTRODUCTION ............................................. 197 I. THE ELECTROCUTION CASES ....................... 201 A. THE KEMMLER DECISION ............................ 201 B. THE KEMMLER EXECUTION ........................... 202 C. FROM IN RE KMMLER to "Evolving Standards" ..... 204 II. THE LOWER COURTS ................................ 206 A. THE CIRCUIT COURTS ................................. 206 B. THE STATE COURTS .................................. 211 C. NEBRASKA - THE LAST HOLDOUT .................. -

The Spanish Garrote

he members of parliament, meeting in Cadiz in 1812, to draft the first Spanish os diputados reunidos en Cádiz en 1812 para redactar la primera Constitución Constitution, were sensitive to the irrational torment that those condemned to Española, fueron sensibles a los irracionales padecimientos que hasta entonces capital punishment had up until then suffered when they were punished. In De- the spanish garrote sufrían los condenados a la pena capital en el momento de ser ajusticiados, y cree CXXVIII, of 24 January, they recognized that “no punishment will be trans- en el Decreto CXXVIII, de 24 de enero, reconocieron que “ninguna pena ha ferable to the family of the person that suffers it; and wishing at the same time that Lde ser trascendental a la familia del que la sufre; y queriendo al mismo tiempo Tthe torment of the criminals should not offer too repugnant a spectacle to humanity que el suplicio de los delincuentes no ofrezca un espectáculo demasiado and to the generous nature of the Spanish nation (…) ” they agreed to abolish the repugnante a la humanidad y al carácter generoso de la Nación española transferable punishment of hanging, replacing it with the garrote. (...) ” acordaron abolir la trascendental pena de horca, sustituyéndola por la Some days earlier, on January 10th, the City Council of Toledo, in compliance de garrote. with a decision of the Real Junta Criminal [Royal Criminal Committee] of the city, Ya unos días antes, el 10 de enero, el ayuntamiento de Toledo, en cum- agreed to the construction of two garrotes and approved the regulations for the plimiento de una providencia de la Real Junta Criminal de la ciudad, acordó construction of the platform. -

The Electric Chair in New York

NEW YORK PBA TROOPER A Piece of History: The Electric Chair in New York neck would not break as expected. In In any event, it was not uncom• Raymond M. Gibbons, Jr., DDS, FAGD such instances, the victim strangled mon- for the subject's heart to con• Forensic Sciences Unit, NYSP slowly, twisting convulsively for as tinue beating for as long as eight long as 15 minutes before death fi• minutes after the trap had been ROM JUNE 4, 1888, until June nally occurred. As one text reported: sprung. That fact troubled many peo• 1, 1965, the lawful method for ". there were repeated examples of ple who feared that the subject might Fputting capital offenders to the fall failing to snap the recipient's be experiencing unintended suffer• death in New York was the ing. All of this led to a electric chair. In the irrev• search for a swift, painless erent jargon of the prisons and humane alternative to and the press the device the scaffold. was nicknamed Old Dr. Alfred Porter South- Sparky, Yellow Mama and wick, a Buffalo, NY, den• Gruesome Gertie among tist and former engineer on others. At the time this Great Lakes freighters, is method of execution was credited with originating adopted, however, it was the ideal of legal punish• hailed as a humane and ment of death by electric• civilized alternative to ity. "Old Electricity," as he methods it supplanted. was known, was convinced Until that time, hanging that this was a much more had been the most com• humane way of bringing^ mon method of executing swift and painless death to condemned murderers. -

Death Row Witness Reveals Inmates' Most Chilling Final Moments

From bloodied shirts and shuddering to HEADS on fire: Death Row witness reveals inmates' most chilling final moments By: Chris Kitching - Mirror Online Ron Word has watched more than 60 Death Row inmates die for their brutal crimes - and their chilling final moments are likely to stay with him until he takes his last breath. Twice, he looked on in horror as flames shot out of a prisoner's head - filling the chamber with smoke - when a hooded executioner switched on an electric chair called "Old Sparky". Another time, blood suddenly appeared on a convicted murderer's white shirt, caking along the leather chest strap holding him to the chair, as electricity surged through his body. Mr Word was there for another 'botched' execution, when two full doses of lethal drugs were needed to kill an inmate - who shuddered, blinked and mouthed words for 34 minutes before he finally died. And then there was the case of US serial killer Ted Bundy, whose execution in 1989 drew a "circus" outside Florida State Prison and celebratory fireworks when it was announced that his life had been snuffed out. Inside the execution chamber at the Florida State Prison near Starke (Image: Florida Department of Corrections/Doug Smith) 1 of 19 The electric chair at the prison was called "Old Sparky" (Image: Florida Department of Corrections) Ted Bundy was one of the most notorious serial killers in recent history (Image: www.alamy.com) Mr Word witnessed all of these executions in his role as a journalist. Now retired, the 67-year-old was tasked with serving as an official witness to state executions and reporting what he saw afterwards for the Associated Press in America.