The National Science Foundation Surveys of Public Understanding of D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educating the Net Generation Diana G

Educating the Net Generation Diana G. Oblinger and James L. Oblinger, Editors Chapter 1: Introduction by Diana Oblinger, EDUCAUSE, and James Oblinger, North Carolina State University Chapter 2: Is It Age or IT: First Steps Toward Understanding the Net Generation by Diana Oblinger, EDUCAUSE, and James Oblinger, North Carolina State University • Introduction • Implications • Asking the Right Questions • Endnotes • Acknowledgments • About the Authors Chapter 3: Technology and Learning Expectations of the Net Generation by Gregory Roberts, University of Pittsburgh–Johnstown • Introduction • Technology Expectations of the Net Generation • Learning Expectations of the Net Generation • Conclusion • Endnotes • About the Author Chapter 4: Using Technology as a Learning Tool, Not Just the Cool New Thing by Ben McNeely, North Carolina State University • Growing Up with Technology • How the Net Gen Learns • Cut-and-Paste Culture • Challenges for Higher Education • The Next Generation • About the Author Chapter 5: The Student’s Perspective by Carie Windham, North Carolina State University • Introduction • Meet Generation Y Not • Filling the Attention Deficit • Reaching the Net Generation in a Traditional Classroom • A Virtual Education: Crafting the Online Classroom • E-Life: The Net Gen on Campus • Outlook for the Future • Endnotes • About the Author ISBN 0-9672853-2-1 © 2005 EDUCAUSE. Available electronically at www.educause.edu/educatingthenetgen/ Chapter 6: Preparing the Academy of Today for the Learner of Tomorrow by Joel Hartman, Patsy Moskal, -

Millennials on Millennials” Shopping Insights Report

FALL 2018 MILLENNIALS ON MILLENNIALS U.S. SHOPPING INSIGHTS IN A NEW ERA Copyright © 2018 The Nielsen Company (US), LLC. WELCOME The fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) market is facing a variety of growth challenges. As large consumer segments age, a new group is GATES HELMS gaining relevance. SENIOR ANALYST Making up 26% of U.S. shopping households, Millennials are the future front-runners in generational spending power. As Millennials, we are the most diverse generational segment to date from an ethnic and racial perspective, and as a result, our perspectives about consumer spending, shopping channels, information transparency, social responsibility and health consciousness are as unique as NICHOLAS KAUFMAN we are individually. SENIOR ANALYST Generalizing and trending the variety of perspectives and life stages present among Millennials can be a challenging task for FMCG companies. As a part of this dynamic generation, we feel uniquely positioned to analyze the data and provide insight into the distinct consumer behaviors of U.S. Millennials. NEERAL MEHTA Focusing on data-driven insights and adding in personal perspectives provides a necessary rich comprehension that can influence the decisions ANALYST of advertisers, manufacturers and retailers. This report provides FMCG organizations with critical knowledge they need as they compete for our attention and our dollars. Within this report, generations are defined as follows: • Greatest Generation: born before 1946 • Baby Boomers: born between 1946 and 1964 NATASHA SAYLOR • Generation X: born between 1965 and 1976 CLIENT MANAGER • Millennials: born between 1977 and 1995, or consumers under 35 as of 2017. This is different from the Millennials on Millennials report on TV and digital news consumption, which categorizes Millennials as 21-37. -

Handbook of Research on Overcoming Digital Divides: Constructing an Equitable and Competitive Information Society

Handbook of Research on Overcoming Digital Divides: Constructing an Equitable and Competitive Information Society Enrico Ferro Istituto Superiore Mario Boella (ISMB), Italy Yogesh Kumar Dwivedi Swansea University, UK J. Ramon Gil-Garcia Centro de Investigación Docencia Económicas, Mexico Michael D. Williams Swansea University, UK Volume I INFORMATION SCIENCE REFERENCE Hershey • New York Director of Editorial Content: Kristin Klinger Senior Managing Editor: Jamie Snavely Assistant Managing Editor: Michael Brehm Publishing Assistant: Sean Woznicki Typesetter: Kurt Smith, Sean Woznicki Cover Design: Lisa Tosheff Printed at: Yurchak Printing Inc. Published in the United States of America by Information Science Reference (an imprint of IGI Global) 701 E. Chocolate Avenue Hershey PA 17033 Tel: 717-533-8845 Fax: 717-533-8661 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.igi-global.com/reference Copyright © 2010 by IGI Global. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or distributed in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without written permission from the publisher. Product or company names used in this set are for identification purposes only. Inclusion of the names of the products or companies does not indicate a claim of ownership by IGI Global of the trademark or registered trademark. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of research on overcoming digital divides : constructing an equitable and competitive information society / Enrico Ferro ... [et al.], editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: "This book presents a comprehensive, integrative, and global view of what has been called the digital divide"-- Provided by publisher. -

The Study of Generations: a Timeless Notion Within a Contemporary Context

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by CU Scholar Institutional Repository University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2016 The tudS y of Generations: A Timeless Notion within a Contemporary Context Lauren M. Troksa University of Colorado Boulder, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/honr_theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Labor History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Troksa, Lauren M., "The tudyS of Generations: A Timeless Notion within a Contemporary Context" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1169. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Honors Program at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Study of Generations: A Timeless Notion within a Contemporary Context By Lauren Troksa Department of History at the University of Colorado Boulder Defended: April 4, 2016 Thesis Advisor: Professor Phoebe Young, Dept. of History Defense Committee: Professor Phoebe Young, Dept. of History Professor Mithi Mukherjee, Dept. of History Professor Vanessa Baird, Dept. of Political Science The Study of Generations: A Timeless Notion within a Contemporary Context Author: Lauren Troksa (University of Colorado Boulder, Spring 2016) Abstract: The study of generations has been timeless. Dating as far back as Plato’s time (428 B.C.E) to present-day (2016), scholars of all fields have used generations to study large trends that emerge over time in specific groups of people. -

Generational Diversity at Work: a Systematic Review of the Research

Working Paper Series 2015/48/OB Generational Diversity at Work: A Systematic Review of the Research Ian C. Woodward INSEAD, [email protected] Pisitta Vongswasdi INSEAD, [email protected] Elizabeth A. More Australian Institute of Management, [email protected] July 2015 - Version 1.0 Note: This paper is part of an ongoing series of research projects in INSEAD’s Leadership and Communication Research Group. For the first time in modern history, workplace demographics now span up to four distinct generations. Therefore, intergenerational diversity is a timely issue, gathering increasing interest amongst academics, organizations and business executives. However, the evidence base in scholarly research on generational diversity at work is often contradictory and unclear. In this study we aim to identify and examine existing empirical research on generational differences in work-related characteristics to inform future focal areas for generational research related to leadership and management; as well as to synthesize the existing evidence of generational differences in a variety of work- related characteristics. We conduct a systematic review of the literature to synthesize empirical research in a rigorous manner (following a disciplined screening process, a final sample of 50 studies is examined). In the analysis, six key themes emerge: communication and technology; work motivators or preferred job characteristics; work values; work attitudes; workplace/career behaviors; and leadership preferences or behaviors. Our systematic review also reveals that the majority of empirical studies provide results which fully or partially support the existence of generational diversity; highlighting the importance of future research to address the potential differing needs and characteristics of each generation as they interact and work within organizations. -

March 2021 Global Consumer Insights Pulse Survey 2 | Pwc Global Consumer Insights Pulse Survey

Four fault lines show a fracturing among global consumers PwC’s March 2021 Global Consumer Insights Pulse Survey 2 | PwC Global Consumer Insights Pulse Survey Introduction One year after the COVID-19 pandemic partially shut down many of the world’s economies, consumers are responding in a way that is accelerating changes that have been percolating for years. Our March 2021 Global Consumer Insights Pulse Survey shows four essential fault lines developing that are creating distinct groups of global consumers. Companies can be more prepared for the future by understanding these emerging cohorts and what their behaviours portend. These four fault lines divide: • consumers who now primarily work from home from those who generally work away from home • younger consumers from older ones • consumers who prioritise health and safety from those who aren’t as safety-conscious • consumers in the Asia-Pacific egionr from those in other regions. 3 | PwC Global Consumer Insights Pulse Survey But before we explore those divides, there are some overall trends that our survey revealed. Despite the impact of COVID-19, in-store In-store Mobile PC Tablet In-store Mobile PC Tablet shopping remains consumers’ channel of choice for daily or weekly shopping. However, mobile 47% shopping continues to steadily accelerate as other types of shopping, including in-store shopping, decline. 41% Mobile shopping is gaining on in-store shopping Q: In the past 12 months, how often have you bought products (e.g., clothes, books, electronics) using the following shopping channels? (Answers shown reflect daily and weekly shopping combined and do not include grocery shopping.) n 2020 n 2021 Note: 2020 survey was city-focused, trend indicative. -

Not All the Same the Generations

The Generations The Baby Boomers Born 1946 to 1964 They entered the world with a boom after World War II. Baby Boomers came of age amid great social change. They saw the civil rights movement unfold, experienced the draft during the Vietnam War and danced through the Summer of Love. Now, as they hit retirement age, Baby Boomers often opt to age at home rather than in a nursing facility. The Silent Generation Born 1928 to 1945 Many men of the Silent Generation missed World War II, but fought for their country during the Korean War. Women began thinking about working outside of the home, although it was a slow process. The Great Depression taught the Silent Generation the 65 and Older value of saving money and spending modestly. In retirement, many find themselves financially stable thanks to generous pensions, a perk that many Not All the Same employers no longer offer. Colorado is experiencing unprecedented growth in its 65 and older Understanding how seniors differ – both in the context of their past and population. This age group is expected to increase by 127 percent their needs in the future – is important. City planners will have to adapt to between 2013 and 2040. We often talk about older adults as one changing housing and lifestyle desires of the Baby Boomers. Policymakers The Greatest Generation group, but in truth they differ in their health needs and expectations will need to understand that longer life expectancy means that we will need for aging. to care for – and pay for – a larger number of the elderly. -

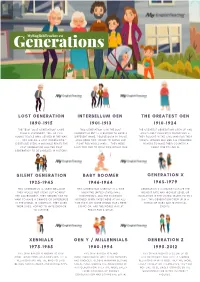

Generations PDF File

GeMyEnnglisheTeacrher.aeu tions LOST GENERATION INTERBELLUM GEN THE GREATEST GEN 1890-1915 1901-1913 1910-1924 THE TERM “LOST GENERATION” CAME THIS GENERATION IS IN THE LOST THE GREATEST GENERATION GREW UP AND FROM A STATEMENT. “ALL OF YOU GENERATION BUT IS SPECIFIED TO HAVE A MOST LIKELY FOUGHT IN WORLD WAR 2. YOUNG PEOPLE WHO SERVED IN THE WAR. DIFFERENT NAME. PEOPLE BORN IN THOSE THEY FOUGHT IN THE CIVIL WAR FOR THEIR . YOU ARE ALL A LOST GENERATION.” AGES WERE TOO YOUNG TO SERVE AND RIGHTS. WOMEN AND MEN ALL COMBINED (GERTRUDE STEIN, A MOVABLE FEAST) THE FIGHT FOR WORLD WAR I... THEY WERE POWERS TO MAKE THEIR COUNTRY A LOST GENERATION WAS THE FIRST ALSO TOO OLD TO FIGHT FOR WORLD WAR GREAT ONE TO LIVE IN. GENERATION TO BE LABELLED IN HISTORY. II. SILENT GENERATION BABY BOOMER GENERATION X 1925-1945 1946-1964 1965-1979 THIS GENERATION IS SILENT BECAUSE THIS GENERATION GREW UP IN A TIME GENERATION X IS KNOWN TO HAVE THE THEY WOULD NOT SPEAK OUT AGAINST WHEN THE UNITED STATES WAS HIGHEST RATE AND HIGHEST LEVEL OF THE GOVERNMENT. THEY SEEMED NOT TO PROSPEROUS, AND THE ECONOMY EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES TO THIS WANT TO MAKE A CHANGE OR DIFFERENCE BOOMED. BIRTH RATES WERE AT AN ALL- DAY. THIS GENERATION GREW UP IN A IN THE WORLD. IN CONTRAST, THEY LIVED TIME HIGH. NO MORE WORLD WARS WERE WORLD OF WARS AND HISTORICAL THEIR LIVES, HOPING TO HAVE ENOUGH GOING ON, AND THE WORLD WAS AT EVENTS. TO SURVIVE. PEACE FOR A WHILE. -

Generational Names in the United States Gen X, Millennials, and Other Generations Through the Years by Matt Rosenberg Updated June 08, 2019

Home Generational Names in the United States Gen X, Millennials, and Other Generations Through the Years by Matt Rosenberg Updated June 08, 2019 Generations in the United States are defined as social groups of people born around the same time who share similar cultural traits, values, and preferences. In the U.S. today, many people readily identify themselves as Millennials, Xers, or Boomers. But these generational names are a fairly recent cultural phenomenon and they vary depending on the source. The History of Naming Generations Historians generally agree that the naming of generations began in the 20th-century. Gertrude Stein is considered the first to have done so. She bestowed the title of Lost Generation on those who had been born around the turn of the century and bore the brunt of service during World War I. In the epigram to Ernest Hemingway's "The Sun Also Rises," published in 1926, Stein wrote, "You are all a lost generation." Generational theorists Neil Howe and William Strauss are generally credited with identifying and naming the 20th-century generations in the U.S. with their 1991 study "Generations." In it, they identified the generation that fought World War II as the G.I. (for Government Issue) Generation. But less than a decade later, Tom Brokaw published "The Greatest Generation," a best-selling cultural history of the Great Depression and World War II, and that namesake stuck. Canadian author Douglas Coupland, born in 1961 at the tail end of the Baby Boom, is credited with naming the generation that followed him. Coupland's 1991 book "Generation X: Tales For an Accelerated Culture," and later works chronicled the lives of 20-somethings and came to be seen by some as defining that era's young. -

Pobierz Realia Dialogu Społecznego W Polsce

Realia dialogu społecznego w Polsce Wnioski z serii seminariów Komitetu Dialogu Społecznego Krajowej Izby Gospodarczej 2016/2017 Warszawa 2017 lsce Po alia dialogu społecznego w Re dialogkig.pl Realia dialogu społecznego w Polsce Wnioski z serii seminariów Komitetu Dialogu Społecznego Krajowej Izby Gospodarczej 2016/2017 rszawa 2017 Wa Warszawa 2017 Wydawca: Komitet Dialogu Społecznego Krajowej Izby Gospodarczej ul. Trębacka 4 00-074 Warszawa e-mail: [email protected] Koordynatorzy publikacji: Magdalena Kowalska Anna Tarnawska Nadzór merytoryczny: Konrad Ciesiołkiewicz, Komitet Dialogu Społecznego KIG Redakcja i korekta: Bridge Sp. z o.o. Projekt graficzny i skład: Piotr Wilk, W2DESIGN Paweł Cwalina, MANIANA STUDIO Druk: e-bit Wydawnictwo&Logistyka Źródła materiałów: Materiały własne Zdjęcia w numerze: Archiwum Polskiej Agencji Prasowej Strona internetowa: www.dialogkig.pl Realia dialogu społecznego w Polsce Wnioski z serii seminariów Komitetu Dialogu Społecznego Krajowej Izby Gospodarczej 2016/2017 Warszawa 2017 Spis treści Wstęp 1 Modele kapitalizmu a perspektywy dialogu społecznego w Polsce 3 Przedsiębiorstwo prywatne a dialog społeczny – w poszukiwaniu spójności 19 Młodzież jako partner dialogu 29 Ubóstwo w Polsce 41 Zarządzanie etyką w przedsiębiorstwie. Temat do rozmowy czy zagadnienie do zarządzania? 55 Nierówności społeczne w Polsce 67 Epilog 79 Zespół Komitetu Dialogu Społecznego KIG 81 Eksperci Komitetu Dialogu Społecznego KIG 84 Wstęp Przymiotniki są kuszące. Jaki?, Jaka?, Który?, Czyj?, Czyje? Tuż za ostatnim znakiem zapytania czeka na nas olbrzymia przestrzeń możliwości i praktycznie nieograniczona liczba odpowiedzi. Taka jest rzeczywistość świata zamknięta w terabajtach słów, idei, poglądów, my- śli i opinii. Dziś dostęp do niej może ograniczać jedynie limit transferu danych. Co poniektórzy skurczyli nawet świat wiedzy do 150 znaków, w których starają się przekazać całą mądrość o sprawach często najważniejszych. -

Patterns Final

‘Generation Me’: A product of circumstance or doomed to repeat? An American Perspective Candidate: Elleanor Benbow (4183022) Patterns of Action Dissertation Word count: 3,746 ‘Generation Me’: A product of circumstance or doomed to repeat? An American Perspective The claim that each generation is not as good as the one that came before it is an age-old tale. However, this essay intends to investigate whether these generations are so-called ‘worse’ 1 due to the events that each generation experiences during its maturation, or due to its pre- determined role throughout time. Schaie (1965) describes a generation as a cohort and individuals that are born around a similar time and who share distinctive and important social or historical events during their lives during periods of critical development. This essay will describe and compare the characteristics of the Baby Boomer generation, Generation X and the Millennial generation and determine whether the traits that are most associated with each generation are the product of the events that have helped shaped their lives, or whether they are due to an ongoing cycle of generations, which has been played out for centuries throughout human history. Though there is much debate regarding the birth dates for each generation, the Baby Boomer generation (hereafter ‘Boomers’) was born during the post-World War II baby boom, between the years of 1946-1964 (Colby & Ortman, 2014), Generation X as being born from 1965- 1981 (Twenge et al., 2010) and Millennials, or ‘Generation Me’ (Twenge, 2006), having been born during or after 1980 (Ng, Schweitzer and Lyons 2010) until the mid-2000s, though Ng, Lyons and Schweitzer argue that due to the debate surrounding the start and end years of each generation that these should be used as frames of reference for the continuous flow of social change, rather than the firm boundaries of birth years. -

Memory, Identity, and the Rhetoric of Quilts J

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Theses & Dissertations English Spring 2011 Memory, Identity, and the Rhetoric of Quilts J. Jane Amelon Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Amelon, J. J.. "Memory, Identity, and the Rhetoric of Quilts" (2011). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, English, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/3gwm-rg16 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds/50 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MEMORY, IDENTITY, AND THE RHETORIC OF QUILTS by J. Jane Amelon B.S. December 1973, University of Missouri M.A. December 1988, Old Dominion University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ENGLISH OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2011 Approved by: David D. Metzger (Director) Joyc^ L. Neff (Menfb^r) Virginia L. Gunn (Member) UMI Number: 3458594 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3458594 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code.