The Expansion and Normalization of Police Militarization in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pleasanton Police Department Pleasanton PD Policy Manual

Pleasanton Police Department Pleasanton PD Policy Manual LAW ENFORCEMENT CODE OF ETHICS As a law enforcement officer, my fundamental duty is to serve the community; to safeguard lives and property; to protect the innocent against deception, the weak against oppression or intimidation and the peaceful against violence or disorder; and to respect the constitutional rights of all to liberty, equality and justice. I will keep my private life unsullied as an example to all and will behave in a manner that does not bring discredit to me or to my agency. I will maintain courageous calm in the face of danger, scorn or ridicule; develop self-restraint; and be constantly mindful of the welfare of others. Honest in thought and deed both in my personal and official life, I will be exemplary in obeying the law and the regulations of my department. Whatever I see or hear of a confidential nature or that is confided to me in my official capacity will be kept ever secret unless revelation is necessary in the performance of my duty. I will never act officiously or permit personal feelings, prejudices, political beliefs, aspirations, animosities or friendships to influence my decisions. With no compromise for crime and with relentless prosecution of criminals, I will enforce the law courteously and appropriately without fear or favor, malice or ill will, never employing unnecessary force or violence and never accepting gratuities. I recognize the badge of my office as a symbol of public faith, and I accept it as a public trust to be held so long as I am true to the ethics of police service. -

POLICING REFORM in AFRICA Moving Towards a Rights-Based Approach in a Climate of Terrorism, Insurgency and Serious Violent Crime

POLICING REFORM IN AFRICA Moving towards a rights-based approach in a climate of terrorism, insurgency and serious violent crime Edited by Etannibi E.O. Alemika, Mutuma Ruteere & Simon Howell POLICING REFORM IN AFRICA Moving towards a rights-based approach in a climate of terrorism, insurgency and serious violent crime Edited by Etannibi E.O. Alemika, University of Jos, Nigeria Mutuma Ruteere, UN Special Rapporteur, Kenya Simon Howell, APCOF, South Africa Acknowledgements This publication is funded by the Ford Foundation, the United Nations Development Programme, and the Open Societies Foundation. The findings and conclusions do not necessarily reflect their positions or policies. Published by African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF) Copyright © APCOF, April 2018 ISBN 978-1-928332-33-6 African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF) Building 23b, Suite 16 The Waverley Business Park Wyecroft Road Mowbray, 7925 Cape Town, ZA Tel: +27 21 447 2415 Fax: +27 21 447 1691 Email: [email protected] Web: www.apcof.org.za Cover photo taken in Nyeri, Kenya © George Mulala/PictureNET Africa Contents Foreword iv About the editors v SECTION 1: OVERVIEW Chapter 1: Imperatives of and tensions within rights-based policing 3 Etannibi E. O. Alemika Chapter 2: The constraints of rights-based policing in Africa 14 Etannibi E.O. Alemika Chapter 3: Policing insurgency: Remembering apartheid 44 Elrena van der Spuy SECTION 2: COMMUNITY–POLICE NEXUS Chapter 4: Policing in the borderlands of Zimbabwe 63 Kudakwashe Chirambwi & Ronald Nare Chapter 5: Multiple counter-insurgency groups in north-eastern Nigeria 80 Benson Chinedu Olugbuo & Oluwole Samuel Ojewale SECTION 3: POLICING RESPONSES Chapter 6: Terrorism and rights protection in the Lake Chad basin 103 Amadou Koundy Chapter 7: Counter-terrorism and rights-based policing in East Africa 122 John Kamya Chapter 8: Boko Haram and rights-based policing in Cameroon 147 Polycarp Ngufor Forkum Chapter 9: Police organizational capacity and rights-based policing in Nigeria 163 Solomon E. -

Quorum National and International News Clippings & Press Releases 9 May 2013

Quorum National and International News clippings & press releases Providing members with information on policing from across Canada & around the world 9 May 2013 Canadian Association of Police Boards 157 Gilmour Street, Suite 302 Ottawa, Ontario K2P 0N8 Tel: 613|235|2272 Fax: 613|235|2275 www.capb.ca BRITISH COLUMBIA ................................................................................................ 4 New approach to mental health calls ............................................................................................................. 4 Victoria police to comply with results of excessive-force hearing, police board says ........... 7 Port Moody welcomes a new police chief .................................................................................................... 8 Former Port Moody Police Chief McCabe died Friday ............................................................................... 9 ALBERTA ................................................................................................................ 10 Alberta death review committee to examine family violence cases ................................................. 10 Police chief seeks protections for undercover officers ....................................................................... 11 RCMP changes allow Mounties to be more ‘nimble’ ........................................................................... 13 New bill to allow Alberta police, schools to share information to aid children ........................ 15 SASKATCHEWAN ................................................................................................. -

The Politics of Global Policing

The Politics of Global Policing Forthcoming as Chapter 9 in Bowling, B., Reiner, R. and Sheptycki, J. (2019) The Politics of the Police (5e). Oxford: Oxford University Press. This is a working draft – please do not cite or quote without permission of the authors. Please contact [email protected] The core argument in this book is as follows. Policing is the aspect of social control that is directed at identifying and rectifying conflict and achieved through surveillance and the use of legitimate violence to impose sanctions. At the heart of the policing task, therefore, are two fundamental paradoxes. First, the police must use the state’s monopoly of coercive violence – a morally dubious means – to preserve peace, order and tranquillity. The resolution of the perpetual scandal caused by the deployment of the ‘diabolical power’ of the police is resolved by the claim that the police represent the democratic will of the people and the rule of law. The second paradox is that ‘not all that is policing lies with the police’. Although the police stand as romantic symbols of crime control, the sources of order and community safety lie, to a large extent, beyond the ambit of the police in the political economy and culture of society (Reiner 2016). The politics of the police in a just society should therefore be geared towards enhancing informal social control and minimizing the need to resort to police intervention so that – when they do respond to occurrences of crime and disorder – their intervention is fair, effective and legitimate. This assertion gives rise to a wide range of questions that are covered in this book, such as the meaning of fairness, effectiveness and legitimacy; how best to ensure that police power can be held accountable to the people that it purports to serve; and about the nature of the political processes that govern policing. -

Police Use of Force Tom Sidney Reports on Operation Go Home

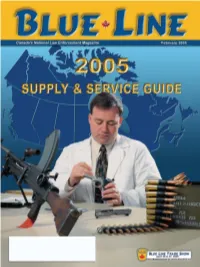

Blue Line Magazine 1 FEBRUARY 2005 Blue Line Magazine 2 FEBRUARY 2005 February 2005 Volume 17 Number 2 Publisher’s Commentary 5 Reduced crime should not reduce agency sizes Blue Line Magazine 12A-4981 Hwy 7 East Ste 254 Training for trouble 6 Markham, ON L3R 1N1 Ontario Provincial Police Tactical Unit Canada Ph: 905 640-3048 Fax: 905 640-7547 Cop’s restraint and a warrior’s mindset 10 Web: www.blueline.ca eMail: [email protected] Training equals success for tactical unit — Publisher — Morley S. Lymburner Spokesperson important part of message 12 eMail: [email protected] It’s not just what is said-but also who says it — General Manager — Mary Lymburner, M.Ed. Thieves caught red handed with bait cars 14 eMail: [email protected] — Editor — So who wants to be Chief? 16 Mark Reesor eMail: [email protected] Not ready to go 17 The real consequences of impaired driving — News Editor — Les Linder eMail: [email protected] Gun control and homicide in Canada 18 Legislation has mixed results — Advertising — Mary Lymburner Welcome to our 2005 Supply & Service Dean Clarke DEEP BLUE 20 Guide. Darrel Harvey is the man at the cen- Bob Murray The bystander effect Kathryn Lymburner tre of this month’s cover. Darrel is a member eMail: [email protected] of the RCMP Planning Branch in Halifax. The BC police will soon patrol from above 21 — Pre-press Production — picture was taken when Darrel worked in the Forensic Firearms section of “H” Division. Del Wall Brockville helps families in Belarus 22 The picture is emblematic of some of the — Contributing Editors — goods and services required by police serv- Communication Skills Mark Giles Community, family mourn RCMP officer 23 Police Management James Clark ices across the country. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. I ti'-J <( ;~ I •Ot, I-ts~ I (~7l( I I I ~ HE HISTORY OF: I I CRIMINAL INTELLIGENCE SERVICE CANADA 1 I - 1978- I I I I I I I Researched and edited by the Central Bureau of C.I.S.C. -

Law Enforcement Information Management Study

SPECIAL STUDY Law Enforcement Information Management Study Alison Brooks, Ph.D. IDC OPINION The objective of this study is to develop a common understanding of Canadian law enforcement's major investigative and operational systems (local, regional, provincial and federal levels) and to develop a common vision towards improved interoperability. To do so this study will provide: . An overview of the central challenges and obstacles to interoperable systems and a view into realistic best practices of interoperability between policing systems . An inventory and short description of the current major national, regional and provincial investigative and operational systems, smaller local systems in the policing community across Canada, and linkages between systems . An assessment of the current levels of interoperability . System-specific interoperability challenges . A delineation of the reasons for a lack of interoperability and an assessment of perceived legal constraints . Recommendations and next steps with respect to the overall state of system interoperability October 2014, IDC #CAN11W TABLE OF CONTENTS P. In This Study 1 Methodology 1 Executive Summary 2 RECOMMENDATIONS 4 Create a National Strategy 4 PIP 2.0/PRP 4 Standards/Interfaces 5 Mugshots 5 MCM 5 RMS 5 CAD 5 BI 5 Digital Evidence Management/ Business Intelligence 5 Situation Overview 6 Introduction 6 Background and a Case for Action 6 The Volume, Variety, Velocity and Value of Digital Evidence 6 Vast Differences in Technology Investments 7 Shifting Operational Paradigms in Policing 7 Technical Obsolescence of Critical Systems 8 Proprietary Systems 8 Lack of Standards 9 Financial Instability 9 System Interoperability Across the Justice Continuum (eDisclosure and DEMS) 9 System Inventory 10 Large National and Provincial Systems 12 Police Information Portal 12 Canadian Police Information Centre 13 Canadian Criminal Real Time Identification Services/Real-Time Identification Project 13 ©2014 IDC #CAN11W TABLE OF CONTENTS — Continued P. -

Arinternational SPECIAL FORCES and SWAT / CT UNITS

arINTERNATIONAL SPECIAL FORCES And SWAT / CT UNITS ABU DHABI Emirate of Abu Dhabi Police Special Unit ========================================================================================== ALBANIA Minster of defence Naval Commandos Commando Brigade - Comando Regiment, Zall Herr - 4 x Commando Battalions - Special Operations Battalion, Farke - Commando Troop School Ministry of Interior Reparti i Eleminimit dhe Neutralizimit te Elementit te Armatosur (RENEA) Unit 88 Reparti i Operacioneve Speciale (ROS), Durres Unit 77 (CT) Shqiponjat (police) "The Eagles" /Forzat e Nderhyrjes se Shpejte (FNSH) - There are 12 FNSH groups throughout Albania . - Albania is divided into 14 districts called prefectures. There is one FNSH group assigned to 11 of these prefectures Garda Kombetare - National Guards ========================================================================================== ALGERIA Ministry of National Defence Units of the Gendarmerie National Special Intervention Detachment (DSI) / Assault & Rapid Intervention unit Special Brigade Garde Republicaine - Republican Guard (presidential escort honour guard & VIP) Units of the DRS (Research & Security Directorate) (internal security, counter- intelligence) Special Unit of the Service Action GIS, Groupe d’Intervention Sppeciale (Special Intervention Group), Blida Army Units - Saaykaa (Commando & CT), Boughar, Medea Wilaya - One Special Forces/Airborne Divisional HQ - 4 x Airborne Regiments - 18th Elite Para-Commando Regiment ('The Ninjas') - The Special Assault /Airborne/Recon Troops -

Police Department Annual Report 2018

Mission Statement The Oak Forest Police Department is committed to providing outstanding law enforcement services. We will enhance the quality of life for our residents by partnering with the community to reduce crime and solve problems. Our mandate is to conduct ourselves with professionalism and excellence to maintain public confidence. Oak Forest Police Department 15440 S. Central Ave Oak Forest, Illinois, 60452 Letter from the Chief of Police On behalf of the men and women of the Oak Forest Police Department, I would like to present the 2018 annual report. The Oak Forest Police Department is committed to providing outstanding law enforcement services. We will enhance the quality of life for our residents by partnering with the community to reduce crime and solve prob- lems. Our mandate is to conduct ourselves with professionalism and excellence to maintain public confidence. 2018 the Oak Forest Police Department. continues to move forward and be innovative in all phases of law en- forcement services, including technology, equipment, and training for our personnel. We must also provide the necessary equipment for our members to allow them to provide the best services possible and in a timely man- ner. We also are committed to providing our members with high quality and effective training to meet the needs of our residents. The police department along with the Oak Forest 911 board has spent considerable time and resources to up- grade our existing emergency communication radio network to provide better service to the residents of Oak Forest and ensure that our officers on patrol have a reliable and effective form of communication. -

Countering Terror Through Community Intelligence and Democratic Policing

This article explores how counterterrorism policing strategies and practices in the United Kingdom have changed in the face of recent terrorist attacks. It consid- ers the evident limitations of these developments and how a local, democratic style of neighborhood policing could be used to manufacture the community intelli- gence “feed” that offers the best probability of prevent- ing and deterring future forms of such violence. These substantive concerns are set against a theoretical back- drop attending to how policing can respond to risks where the contours of the threat are uncertain. The analysis is Policing informed by interviews with U.K. police officers involved in intelligence and counterterrorism work conducted Uncertainty: during the early part of 2005. Keywords: counterterrorism; democratic policing; Countering neighborhood policing; signal crimes; Terror through community intelligence; uncertainty Community errorist violence is a form of communica- Intelligence and Ttive action. Designed to impact upon pub- lic perceptions by inducing fear in pursuit of Democratic some political objective, violence is dramaturgi- cally enacted as a solution to a sociopolitical Policing power imbalance (Karstedt 2003). It is thus ulti- mately an attempt at social control, where a less powerful actor seeks to exert influence over the norms, values, and/or conduct of another more powerful grouping (Black 2004). By Martin Innes is a senior lecturer in sociology at the MARTIN INNES University of Surrey. He is author of the books Investi- gating Murder (Clarendon Press, 2003) and Under- standing Social Control (Open University Press, 2003), as well as articles in the British Journal of Sociology and the British Journal of Criminology. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. FIRST REPORT AN DUCATION PROGRAM AND INTERAGENCY MODEL FOR POLICE OFFICERS ON ELDER ABUSE AND NEGLECT HV 8079 .225 E25 1993 FIRST REPORT AN 4DUCATION PROGRAM AND INTERAGENCY MODEL FOR POLICE OFFICERS ON ELDER ABUSE AND NEGLECT SOLICiTOR G!1NERAL CANADA JUN JUIN § 1997 soworrÊtni Gtemi. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. Government Gouvernement 1*1 of Canada du Canada Canaa REPORT OF THE FEDERAL AD HOC INTERDEPARTMENTAL WORKING GROUP ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS ON CHILD SEX OFFENDERS SCREENING OF VOLUNTEERS