Ambrose Bierce Brief Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Collected Works of Ambrose Bierce

m ill iiiii;!: t!;:!iiii; PS Al V-ID BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Henrg W, Sage 1891 B^^WiS _ i.i|j(i5 Cornell University Library PS 1097.A1 1909 V.10 The collected works of Ambrose Blerce. 3 1924 021 998 889 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021998889 THE COLLECTED WORKS OF AMBROSE BIERCE VOLUME X UIBI f\^^°\\\i COPYHIGHT, 1911, Br THE NEALE PUBLISHING COMPANY CONTENTS PAGE THE OPINIONATOR The Novel 17 On Literary Criticism 25 Stage Illusion 49 The Matter of Manner 57 On Reading New Books 65 Alphab£tes and Border Ruffians .... 69 To Train a Writer 75 As to Cartooning 79 The S. p. W 87 Portraits of Elderly Authors .... 95 Wit and Humor 98 Word Changes and Slang . ... 103 The Ravages of Shakspearitis .... 109 England's Laureate 113 Hall Caine on Hall Gaining . • "7 Visions of the Night . .... 132 THE REVIEWER Edwin Markham's Poems 137 "The Kreutzer Sonata" .... 149 Emma Frances Dawson 166 Marie Bashkirtseff 172 A Poet and His Poem 177 THE CONTROVERSIALIST An Insurrection of the Peasantry . 189 CONTENTS page Montagues and Capulets 209 A Dead Lion . 212 The Short Story 234 Who are Great? 249 Poetry and Verse 256 Thought and Feeling 274 THE' TIMOROUS REPORTER The Passing of Satire 2S1 Some Disadvantages of Genius 285 Our Sacrosanct Orthography . 299 The Author as an Opportunity 306 On Posthumous Renown . -

Vanausdall on Duncan and Klooster, 'Phantoms of a Blood- Stained Period: the Complete Civil War Writings of Ambrose Bierce'

H-Indiana Vanausdall on Duncan and Klooster, 'Phantoms of a Blood- Stained Period: The Complete Civil War Writings of Ambrose Bierce' Review published on Thursday, August 1, 2002 Russell Duncan, David J. Klooster, eds. Phantoms of a Blood-Stained Period: The Complete Civil War Writings of Ambrose Bierce. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002. xiv + 343 pp. $60.00 (cloth) ISBN 1-55849-327-1; $19.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-55849-328-5. Reviewed by Jeanette Vanausdall (independent historian, Indianapolis)Published on H-Indiana (August, 2002) Writer as Witness Writer as Witness Phantoms of a Blood-Stained Period: The Complete Civil War Writings of Ambrose Bierce, edited by Russell Duncan and David J. Klooster, is a useful addition to the small assortment of Bierce collections available to students and scholars today. Bierce was perhaps the most significant American writer to have actually been a soldier throughout the war. For this reason alone he would be worth reading. But Bierce holds special interest for the student of the war because his work was so markedly different from most first-hand accounts, particularly the revisionist regimental histories that littered the literary landscape during the decades after the war. Rather than glorify the war and the soldiers who fought it, Bierce insisted upon exposing the bloodiness, brutality, stupidity, fear and cowardice to which he had been witness. Bierce genuinely deplored the war, but he also seemed to revel in his reputation as the foremost malcontent of his generation. Born in Meigs County, Ohio in 1842, Bierce's family was living in Indiana when the war broke out. -

“An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” (1891) Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914?)

ANALYSIS “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” (1891) Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914?) “[Stephen] Crane made no comment whatever, sliding his glass of whiskey up and down. Later he asked whether [journalist Robert H.] Davis had read Bierce’s ‘Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.’ ‘Nothing better exists. That story contains everything. Move your foot over,’ and he wanted to know what Bierce was like personally--especially whether he had plenty of enemies. ‘More than he needs,’ Davis said. ‘Good,’ said Crane. ‘Then he will become an immortal,’ and shook hands, just shaking his head when Davis gestured toward his untouched whiskey.” [1897] John Berryman Stephen Crane (World/Meridian 1962) 170 His best and most reprinted story is “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” A captured Confederate is hung from a bridge by Union troops, but the rope breaks--and he falls into the creek! He escapes ashore and finally makes it back to his plantation: “He must have traveled the entire night.” He rushes toward the open arms of his wife coming down from the veranda to embrace him. “As he is about to clasp her he feels a stunning blow upon the back of the neck... His body, with a broken neck, swung gently from side to side beneath the timbers of the Owl Creek Bridge.” The surprise ending and the gothic horror are in the tradition of Poe. As a whole, however, the story is a brilliant early example of Modernism, combining techniques of Realism, Impressionism and Expressionism with Naturalistic themes: “Objects were represented by their colors only; circular horizontal -

Geography and Warfare in Ambrose Bierce's Civil War Texts

BENEDICT VON BREMEN Battlefi eld Topography: Geography and Warfare in Ambrose Bierce’s Civil War Texts Whether in camp or on the march, in barracks, in tents, or en bivouac, my duties as topographical engineer kept me working like a beaver – all day in the saddle and half the night at my drawing table. It was hazardous work […] Our frequent engagements with the Confederate outposts, patrols, and scouting parties [...] fi xed in my memory a vivid and apparently imperishable picture of the locality – a picture serving instead of accurate fi eld notes, which, indeed, it was not always convenient to take, with carbines cracking, sabers clashing, and horses plunging all about. These spirited en- counters were observations entered in red.1 A quarter-century ago I was myself a soldier […] To this day I cannot look over a landscape without noting the advantages of the ground for attack or defense; here is an admirable site for an earthwork, there a noble place for a fi eld battery.2 No country is so wild and diffi cult but men will make it a theatre of war […].3 Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (1842-?), although “rediscovered”4 every so oft en, belongs to the most well-known authors of Gilded Age and fi n de siècle America. “Bitter Bierce,” sarcastic commentator of his time and countrymen, was among the most well-known journalists on the U.S. west coast from the 1880s onward and attained some national fame at the turn of the century.5 His stories “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” and “Chickamauga” are U.S. -

The Early Years Ambrose Bierce Didn't Rise to Writing Fame in Quite

Introduction – The Early Years Ambrose Bierce didn’t rise to writing fame in quite the same glory as Edgar Allen Poe, but in many ways his writing style and story telling was no less compelling. Bierce left his mark in history during this time period as a journalist, humorist, satirist, and editor. He developed his character, credentials and influence through his writing. He is best known for his Civil War short stories and his very own ‘Devil’s Dictionary’. The unique elements of Bierce’s writing provided not only entertainment, but also information. Through his writing he was able to share his opinions in an influential way which gave him both prestige and power. Ambrose Bierce was born on a farm, the tenth child of thirteen children, all with names beginning with ‘A’, in Elkart, Ohio .It appears that Bierce the writer and Bierce the man were consciously developed by him through a series of half truths. What is known about Ambrose Bierce is more what he wanted you to know. With his fame came the scrutiny of his critics. He earned the reputation of being known as Bitter Bierce, and his critics could be harsh. Walter Neale’s book about the Ambrose Bierce’s life is a tribute to the author through the eyes of a friend. Even Neale has difficulty reconciling the many contradictions surrounding the truth about Ambrose Bierce. Neale writes after researching Bierce’s early life, “It is now clear to me why Bierce misrepresented his early life. He was ashamed of his lowly estate while in Elkhart (Neale, p39).” Ambrose Bierce repeatedly told Neale the story of his early life saying that “he was born on a farm in the Western Reserve, in Ohio, and had there remained until he was about seventeen, when he tired of farm life, ran away from home, to Chicago, and had there engaged in free-lance work for newspapers until he enlisted in the Union Army at the outbreak of the Civil War.” With great pride he would continue that “he came from an old New England family, cultured, and of local distinction. -

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge Bierce, Ambrose

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge Bierce, Ambrose Published: 1988 Categorie(s): Fiction, Short Stories, War & Military Source: http://gutenberg.org 1 About Bierce: Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – 1914?) was an American ed- itorialist, journalist, short-story writer and satirist. Today, he is best known for his short story, An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge and his satirical dictionary, The Devil's Dictionary. The sardonic view of human nature that informed his work – along with his vehemence as a critic – earned him the nickname, "Bitter Bierce." Despite his reputation as a searing critic, however, Bierce was known to encourage younger writers, including the poet, George Sterling and the fiction writer, W. C. Morrow. In 1913, Bierce traveled to Mexico to gain a firsthand perspective on that country's ongoing revolution. While traveling with rebel troops, the eld- erly writer disappeared without a trace. Also available on Feedbooks for Bierce: • The Damned Thing (1898) Copyright: This work is available for countries where copyright is Life+70. Note: This book is brought to you by Feedbooks http://www.feedbooks.com Strictly for personal use, do not use this file for commercial purposes. 2 I A man stood upon a railroad bridge in northern Alabama, looking down into the swift water twenty feet below. The man's hands were behind his back, the wrists bound with a cord. A rope closely encircled his neck. It was attached to a stout cross-timber above his head and the slack fell to the level of his knees. Some loose boards laid upon the ties supporting the rails of the railway supplied a footing for him and his execution- ers—two private soldiers of the Federal army, directed by a sergeant who in civil life may have been a deputy sheriff. -

Shiloh: Bloody Sacrifice That Changed the Arw

North Alabama Historical Review Volume 1 North Alabama Historical Review, Volume 1, 2011 Article 14 2011 Shiloh: Bloody Sacrifice that Changed the arW Jeshua Hinton Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.una.edu/nahr Part of the Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hinton, J. (2011). Shiloh: Bloody Sacrifice that Changed the arW . North Alabama Historical Review, 1 (1). Retrieved from https://ir.una.edu/nahr/vol1/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNA Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Alabama Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNA Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles 161 Shiloh: Bloody Sacrifice that Changed the War Jeshua Hinton The Battle of Shiloh effected a great change on how the American people and its soldiers viewed and fought the Civil War. William Tecumseh Sherman is famous for stating “war is hell,” and Shiloh fit the bill. Shelby Foote writes: This was the first great modern battle. It was Wilson’s Creek and Manassas rolled together, quadrupled, and compressed into a smaller area than either. From the inside it resembled Armageddon […] Shiloh’s casualties [roughly 23,500-24,000], was more than all three of the nation’s previous wars.1 The battle itself was a horrific affair, but Shiloh was simply more than numbers of killed, or the amount of cannon fired, or some other quantifiable misery. The deaths at Shiloh made America comprehend what type of cost would be exacted to continue the war, and was a foreshadowing of the blood-letting that lie ahead. -

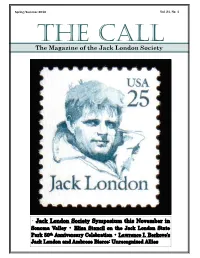

The Call Spring-Summer 2010

Spring/Summer 2010 Vol. 21, No. 1 THE CALL The Magazine of the Jack London Society • Jack London Society Symposium this November in Sonoma Valley • Elisa Stancil on the Jack London State Park 50th Anniversary Celebration • Lawrence I. Berkove’s Jack London and Ambrose Bierce: Unrecognized Allies 2 2010 Jack London Symposium The Jack London Society in Sonoma President Thomas R. Tietze, Jr. ————————— Wayzata High School, Wayzata, MN Vice President November 4-6, 2010 Gary Riedl Hyatt Vineyard Creek Hotel and Spa Sonoma County Wayzata High School, Wayzata, MN Executive Coordinator 170 Railroad Street Jeanne C. Reesman Santa Rosa, CA 95401 University of Texas at San Antonio Advisory Board (707) 284-1234 Sam S. Baskett Michigan State University The Symposium returns this fall to Sonoma Valley to celebrate Lawrence I. Berkove th University of Michigan-Dearborn the 20 anniversary of the founding of the Society. The Hyatt Kenneth K. Brandt Vineyard Creek is offering a discounted room rate of $160 double Savannah College of Art and Design or single. Reservations should be made by calling 1-800- Donna Campbell 233-1234 before the cut-off date of October 1, 2010. Be Washington State University sure to mention that you are with the Jack London Symposium. Daniel Dyer Western Reserve University The Symposium registration will be $125, $85 retiree, and $50 Sara S. "Sue" Hodson graduate student. Events will include: Huntington Library Holger Kersten University of Magdeburg A cocktail reception on Thursday evening Earle Labor Centenary College of Louisiana Sessions: papers, roundtables, and films Joseph R. McElrath Florida State University A picnic and tour of the Jack London Ranch Noël Mauberret Lycée Alain Colas, Nevers, France A visit to Kenwood or Benziger Winery Susan Nuernberg University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh A luncheon on Saturday Christian Pagnard Lycée Alain Colas, Nevers, France Gina M. -

TOPOPHONES in RAY BRADBURY's SCIENCE FICTION Nataliya Panasenko University of SS Cyril and Methodius in Trnava, Trnava, Slovakia

© 2018 N. Panasenko Research article LEGE ARTIS Language yesterday, today, tomorrow Vol. III. No 1 2018 WHERE, WHY, AND HOW? TOPOPHONES IN RAY BRADBURY'S SCIENCE FICTION Nataliya Panasenko University of SS Cyril and Methodius in Trnava, Trnava, Slovakia Panasenko, N. (2018). Where, why, and how? Topophones in Ray Bradbury's science fiction. In Lege artis. Language yesterday, today, tomorrow. The journal of University of SS Cyril and Methodius in Trnava. Warsaw: De Gruyter Open, 2018, III (1), June 2018, p. 223-273. DOI: 10.2478/lart-2018-0007 ISSN 2453-8035 Abstract: The article highlights the category of literary space, connecting different topophones with the author's worldview. Topophones in the works by Ray Bradbury are used not only for identifying the place where the events unfold but they equally serve as the background to the expression of the author's evaluative characteristics of the modern world, his attitude to science, the latest technologies, and the human beings who are responsible for all the events, which take place not only on the Earth, but also far away from it. Key words: chronotope, chronotype, topophone, author's worldview, microtoponym, Biblical allusions. Almost no one can imagine a time or place without the fiction of Ray Bradbury ("Washington Post") 1. Introduction The literary critic Butyakov (2000) once called Ray Bradbury one of the most prominent writers of the 20th century, "A Martian from Los Angeles". This metaphor containing two topophones shows how important literary space was for the author who represented the genre of science fiction. Bradbury violates the laws of nature and sends his readers to the distant future to conquer other planets or readily makes them travel to the past. -

Jack London's South Sea Narratives. David Allison Moreland Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 Jack London's South Sea Narratives. David Allison Moreland Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Moreland, David Allison, "Jack London's South Sea Narratives." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3493. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3493 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Ambrose Bierce's Stylization of the Civil War

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos. n.º 7 (2000), pp. 179 - 188 NATURALIST HISTORIOGRAPHY: AMBROSE BIERCE'S STYLIZATION OF THE CIVIL WAR AITOR lBARROLA-ARMENDARIZ Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao Historical narratives are not only models of past events and processes, but also metaphorical statements which suggest a relation of similitude between such events and processes and the story types that we conventionally use to endow the events of our lives with culturally sanctio ned meanings. Hayden White, Tropics of Discourse. It is by now a widely accepted assumption among historians that their attempts at refamiliarizing us with the events of the past are not solely dependent upan the documented facts they gather. History scholars have leamt that the shapes of the rela tionships that they necessarily project on past events in arder to make sense of them a.re as important as the information allowing them to determine «what really happe ned.» Certainly, no historical account would bear much light on that information if it were not configured according to the precepts of one of the pregeneric plot structures conventionally used in our culture. There is therefore a peremptory need in all histori cal accounts - not unlike the one active in works of fiction- to make use of a language appropriate to «ernplot» the given sequences of historical events into coherent who les.' Historians have found little resort in the technical language of the sciences in this regard, and so they have accommodated the reported events to a figurative language 1. Cf. Hayden Whitc, Metahistory: 71ie Historical Ima¡:i11atio11 in Nineteenth-Ce11t11ry Euro - pe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univcrsity Press, 1973), especially its introduction. -

Foster Family Collection of Ambrose Bierce Materials M2146

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8736x1m No online items Guide to the Foster Family Collection of Ambrose Bierce Materials M2146 Miles Kurosky & Franz Kunst Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Foster Family M2146 1 Collection of Ambrose Bierce Materials M2146 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Foster family collection of Ambrose Bierce materials source: Elkhart County Historical Society Identifier/Call Number: M2146 Physical Description: 3.0 Linear Feet: 2 boxes, 1 half-box, 1 flat box Date (inclusive): 1858-1986 Content Description The collection consists of correspondence (including one letter from Ambrose Bierce to a family member), photographs, maps, field notes, receipts, dispatches, telegrams, and printed material, chiefly relating to the Civil War career of Bierce as a surveyor as well as his extended family in Indiana, especially sister Almeda Sophia Bierce Pittenger (the original source of this collection), father Marcus Aurelius and brothers Albert and Addison Bierce. Of particular note to Civil War historians are the series of maps produced by the Union army's Army of the Cumberland on the Chattanooga Campaign, reflecting the borders between Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama. Of the paper and linen printed maps, some have annotations, and most credit Captain William Emery Merrill. A few note that they were created from information from "captured rebel engineers." There are also maps drawn by Bierce himself. Note that Stanford's Ambrose Bierce Papers also contain material concerning the Civil War, including the sketchbook Bierce kept while serving as a Union topographer with the staff of General Hazen.