Reassessing the Voluntary Siting Process for A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pembina Pipeline June, 2007

Pembina Pipeline June, 2007 “Our purpose is to ensure the delivery of an excellent education to our students so they become contributing members of society.” Sharpen the saw!! Take time for yourself In Stephen Covey’s book The 7 Habits of Highly deals with how we communicate and relate with Effective People, he speaks to being proactive, one another, our empathy toward folks. putting first things first, beginning with the end in mind and other habits all leading to the 7th So with that being said, how are we getting Habit: Sharpening the Saw. ready for the summer? Did we take care of ourselves these past 10 months? I know we To those who have taken the program or read were taking the time to attend to the Alberta the book, the habit “to sharpen the saw” refers to Initiative for School Improvement, Professional allocating time to take care of our physical, Learning Communities, Assessment for spiritual, mental and social/emotional well Learning, Student Engagement, Professional being. Growth, Evaluation, Education Plans, Budgets, Annual Reports, Grade Level of Achievement, You come upon someone in the woods sawing School Superintendent Richard Harvey sharpens his saw by cutting this log with Student Services, Professional Development, down a tree. They look exhausted from working Deputy Superintendent Colleen Symyrozum- Provincial Achievement Tests, Diploma Exams for hours. You suggest they take a break to Watt at Fort Assiniboine School. and the list can go on; all related to teaching sharpen the saw. They might reply, “I don’t have and learning. time to sharpen the saw, I’m too busy sawing!” Habit 7 is taking the time to sharpen the saw. -

Woodlands County 11

Woodlands County 11 Points of Interest & Facilities 1 E.S. Huestis Demonstration Forest 2 Eagle River Casino 16 3 Whitecourt Airport 4 Forest Interpretive Centre 5 Fort Assiniboine Museum 15 12 6 World’s Largest Wagon Wheel and Pick 8 14 18 9 10 13 17 Parks, Campgrounds and Day Use Areas 1 Groat Creek Day Use Area and Group Campground 2 Eagle Creek Campground 3 Hard Luck Canyon 4 Little McLeod Lake (Carson Pegasus Provincial Park) 5 McLeod Lake (Carson Pegasus Provincial Park) 7 6 Blue Ridge Spray Park 7 Blue Ridge Recreation Area Community Halls Lookout Points 8 Goose Lake Campground 1 Westward Community Centre 1 Athabasca River Lookout 9 Goose Lake Day Use Area 2 Anselmo Community Centre 2 Coal Mine Hill Lookout 3 Blue Ridge Community Hall 10 Schuman Lake Campground and Day Use Area 4 Goose Lake Community Hall 5 Topland Community Hall Recreation Areas 11 Centre of Alberta 4 6 Fort Assiniboine Legion 1 Tubing Access (Start) 12 Freeman River RV Park 7 Timeu Community Hall 2 Tubing Take Out (Finish) 13 Mouth of the Freeman River 3 Allan & Jean Millar Centre Day Use Area 14 Woodlands RV Park 4 Blue Ridge Skating Rink Off-Highway Vehicle Areas and River Marina and Playground 1 Eagle River 15 Horse Creek Ranch Snowmobile Staging Area 5 Anselmo Skating Rink, Playground & Ball Diamond 16 Fort Assiniboine Sandhills 2 Whiteridge MX Park Wildland Provincial Park 3 Timeu Off-Highway Vehicle 6 Fort Assiniboine Skating Rink 17 Fort Assiniboine Park and Recreation Area Garter Snake Hibernaculum 4 Goat Creek Snowmoblie Staging Area 18 Fort Assiniboine Boat Launch Find out more at www.woodlands.ab.ca. -

Northwest Territories Territoires Du Nord-Ouest British Columbia

122° 121° 120° 119° 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° n a Northwest Territories i d i Cr r eighton L. T e 126 erritoires du Nord-Oues Th t M urston L. h t n r a i u d o i Bea F tty L. r Hi l l s e on n 60° M 12 6 a r Bistcho Lake e i 12 h Thabach 4 d a Tsu Tue 196G t m a i 126 x r K'I Tue 196D i C Nare 196A e S )*+,-35 125 Charles M s Andre 123 e w Lake 225 e k Jack h Li Deze 196C f k is a Lake h Point 214 t 125 L a f r i L d e s v F Thebathi 196 n i 1 e B 24 l istcho R a l r 2 y e a a Tthe Jere Gh L Lake 2 2 aili 196B h 13 H . 124 1 C Tsu K'Adhe L s t Snake L. t Tue 196F o St.Agnes L. P 1 121 2 Tultue Lake Hokedhe Tue 196E 3 Conibear L. Collin Cornwall L 0 ll Lake 223 2 Lake 224 a 122 1 w n r o C 119 Robertson L. Colin Lake 121 59° 120 30th Mountains r Bas Caribou e e L 118 v ine i 120 R e v Burstall L. a 119 l Mer S 117 ryweather L. 119 Wood A 118 Buffalo Na Wylie L. m tional b e 116 Up P 118 r per Hay R ark of R iver 212 Canada iv e r Meander 117 5 River Amber Rive 1 Peace r 211 1 Point 222 117 M Wentzel L. -

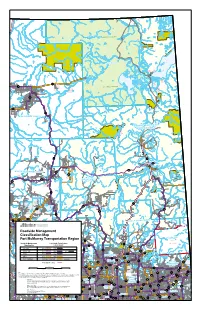

Roadside Management Classification

I.R. I.R. 196A I.R. 196G 196D I.R. 225 I.R. I.R. I.R. 196B 196 196C I.R. 196F I.R. 196E I.R. 223 WOOD BUFFALO NATIONAL PARK I.R. Colin-Cornwall Lakes I.R. 224 Wildland 196H Provincial Park I.R. 196I La Butte Creek Wildland P. Park Ca ribou Mountains Wildland Provincial Park Fidler-Greywillow Wildland P. Park I.R. 222 I.R. 221 I.R. I.R. 219 Fidler-Greywillow 220 Wildland P. Park Fort Chipewyan I.R. 218 58 I.R. 5 I.R. I.R. 207 8 163B 201A I.R . I.R. I.R. 201B 164A I.R. 215 163A I.R. WOOD BU I.R. 164 FFALO NATIONAL PARK 201 I.R Fo . I.R. 162 rt Vermilion 163 I.R. 173B I.R. 201C I.R. I.R. 201D 217 I.R. 201E 697 La Crete Maybelle Wildland P. Park Richardson River 697 Dunes Wildland I.R. P. Park 173A I.R. 201F 88 I.R. 173 87 I.R. 201G I.R. 173C Marguerite River Wildland Provincial Park Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park I.R. 174A I.R. I.R. 174B 174C Marguerite River Wildland I.R. Provincial Park 174D Fort MacKay I.R. 174 88 63 I.R. 237 686 Whitemud Falls Wildland FORT Provincial Park McMURRAY 686 Saprae Creek I.R. 226 686 I.R. I.R 686 I.R. 227 I.R. 228 235 Red Earth 175 Cre Grand Rapids ek Wildland Provincial Park Gipsy Lake I.R. Wildland 986 238 986 Cadotte Grand Rapids Provincial Park Lake Wildland Gregoire Lake Little Buffalo Provincial Park P. -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

Traditional Knowledge Overview for the Athabasca River Watershed ______

Traditional Knowledge Overview for the Athabasca River Watershed __________________________________________ Contributed to the Athabasca Watershed Council State of the Watershed Phase 1 Report May 2011 Brenda Parlee, University of Alberta The Peace Athabasca Delta ‐ www.specialplaces.ca Table of Contents Introduction 2 Methods 3 Traditional Knowledge Indicators of Ecosystem Health 8 Background and Area 9 Aboriginal Peoples of the Athabasca River Watershed 18 The Athabasca River Watershed 20 Livelihood Indicators 27 Traditional Foods 30 Resource Development in the Athabasca River Watershed 31 Introduction 31 Resource Development in the Upper Athabasca River Watershed 33 Resource Development in the Middle Athabasca River Watershed 36 Resource Development in the Lower Athabasca River Watershed 37 Conclusion 50 Tables Table 1 – Criteria for Identifying/ Interpreting Sources of Traditional Knowledge 6 Table 2 – Examples of Community‐Based Indicators related to Contaminants 13 Table 3 – Cree Terminology for Rivers (Example from northern Quebec) 20 Table 4 – Traditional Knowledge Indicators for Fish Health 24 Table 5 – Chipewyan Terminology for “Fish Parts” 25 Table 6 – Indicators of Ecological Change in the Lesser Slave Lake Region 38 Table 7 – Indicators of Ecological Change in the Lower Athabasca 41 Table 9 – Methods for Documenting Traditional Knowledge 51 Figures Figure 1 – Map of the Athabasca River Watershed 13 Figure 2 – First Nations of British Columbia 14 Figure 3 – Athabasca River Watershed – Treaty 8 and Treaty 6 16 Figure 4 – Lake Athabasca in Northern Saskatchewan 16 Figure 5 – Historical Settlements of Alberta 28 Figure 6 – Factors Influencing Consumption of Traditional Food 30 Figure 7 – Samson Beaver (Photo) 34 Figure 8 – Hydro=Electric Development – W.A.C Bennett Dam 39 Figure 9 – Map of Oil Sands Region 40 i Summary Points This overview document was produced for the Athabasca Watershed Council as a component of the Phase 1 (Information Gathering) study for its initial State of the Watershed report. -

6.9 Wildlife Management Unit 350 Moose Section Authors

6.9 Wildlife Management Unit 350 moose Section Authors: Al Fontaine and Robb Stavne Historically, WMU 350 was part of Alberta’s Northern Moose Management Program and was surveyed annually over the winters of 1993/94 to 1997/98 (Lynch 1997). The WMU was again surveyed during the winter of 2001/02. Attempts were made to survey the WMU during the winter of 2005/06, but poor weather and snow conditions forced the cancellation of the survey in its early stages. WMU 350 receives substantial hunting pressure by hunters from First Nations and Métis communities, and it is also a highly desirable WMU for recreational hunters given historical moose populations in the WMU, ease of access, and relative proximity to major urban centres. Therefore, regular moose surveys in WMU 350 are important to assess moose population status and trends in order to properly manage the resource. Current information on moose populations and distribution is also required for proper habitat and land use management. 6.9.1 Study area WMU 350 is delimited to the north by the shorelines of Lesser Slave Lake and the Lesser Slave River from Kinuso to Smith, to the west and southwest by Highway 33 from Kinuso to the Peace Pipeline west of Fort Assiniboine, and to the east and southeast by the Athabasca River from Smith to the ferry on the Athabasca River west of Vega (Figure 16). The town of Slave Lake and parts of the town of Swan Hills are found within the boundaries of the WMU. The only major lake present within the WMU is Mitsue Lake, which is surrounded by the Mitsue Lake Industrial Park. -

Fort Assiniboine Park Guide

Alberta’s wildland parks preserve There are sand dunes in the eastern two-thirds © Gord Court and protect natural landscapes and Site Description & of the park that are part of a larger dune field Contact extending northeast along the Athabasca River. ecological processes. They also The stabilized dune field is in a transitional Alberta Tourism, Parks & Recreation provide opportunities for backcountry Location state between transverse and parabolic dunes. Stony Plain District Office recreation; in some wildland parks Parabolic dunes are crescent-shaped, with Phone: (780) 960–8170 Fort Assiniboine Fort Assiniboine Sandhills is located in the central horns facing upwind. Transverse dunes are mixedwood subregion of the Boreal Forest trails, staging areas and/or primitive linear-shaped and form at right angles to the General Provincial Park Information Natural Region. The park’s diverse landscapes campsites are provided to minimize prevailing wind. The western part of the park is Web: albertaparks.ca Sandhills include steep valley walls and river flats; springs predominately wetlands consisting of sedge/grass Toll Free: 1–866–427–3582 visitor impacts on natural heritage and wetlands; stabilized sand dunes; and pine, Wildland Provincial Park fens, black spruce/larch bogs, shrub fens and Phone: (780) 427–3582 values. white spruce and aspen forests. The park marshes. includes Pemmican Island and other islands Fire Bans in Alberta PA R K G U I D E Fort Assiniboine Sandhills was designated a in the Athabasca River. Access to the park is There are three distinct grassland types in the Web: albertafirebans.ca wildland park in 1997. It covers approximately 66 via Highway 661 from the west through Ft. -

264 March 1988

RESEARCH BULLETIN No. 264 March 1988 Parks Canada Archaeology in Western Region, 1984 Introduction The Western Region Archaeological Research Unit of Parks Canada administered 90 projects in Alberta and British Columbia in 1984 ( See Table 1). All projects were under the financial management and administrative responsibility of the Regional Archaeologist of the Historical and Archaeological Research Section. Projects were completed through utilization of in-house resources, under contract, or through special agreements. This was an increase of 54 per cent over projects covered under permit in 1983. Seventy-two projects were associated with various National Parks and National Historic Parks and Sites in Alberta while 18 projects were related to British Columbia parks and sites. Of these, 57 involved HRIAs (areal and linear site surveys and assessments), eight mitigations (salvage and conservation archaeology involving major or test excavations) and 25 special projects (support activities, special studies, overviews and research). Most of the heritage resources impact and assessment projects were conducted by Regional Salvage Archaeologist Ian Sumpter. Studies were completed in Elk Island, Waterton Lakes, Jasper, Yoho, Glacier and Banff National Parks. Project Archaeologist Rod Pickard completed three short-term mitigative projects in Jasper National Park at the mining community of Environment Environnement Cette publication est disponible en français. Canada Canada Parks Pares -2- Pocahontas (ca. 1908-21), the fur trade site of Jasper House (ca. 1830-84), and at two prehistoric sites (FfQm-26, FfQm-34) on Patricia Lake. Major investigations were continued at the early man Vermilion Lakes Site in Banff National Park under the direction of Project Archaeologist Daryl Fedje and assisted by Senior Research Assistant Jim White. -

More Testing, New Technology Asked of Hazardous Waste Incinerator

For Immediate Release October 11, 2016 More testing, new technology asked of hazardous waste incinerator The Swan Hills (hazardous waste) Treatment Centre is located at the top of the Swan Hills, 70 kilometres as the crow flies from the Town of Slave Lake, 80 km S from Kinuso, about 160 km due west from the Town of Athabasca, and 65 km NE from Fort Assiniboine. The plant is owned by Alberta Infrastructure. SHTC is operated by SUEZ Environmental, in a contract with the Government of Alberta. We wrote a challenge to the facility’s 10 year Approval, and included the names of many local people who joined us in expressing concerns. When our concerns about operations at this facility were recognized by Alberta Environment and Parks in August of 2015, we were excited to get them addressed. Keepers of the Athabasca participated in our first meeting with SUEZ Environmental and Alberta Environment and Parks on September 9, 2016. We agreed to work together to address these issues: Human and environmental effects of ‘unplanned’ and ‘allowable’ PCB, dioxin, and furan releases Ever since the plant (then the Swan Hills Toxic Waste Treatment Facility) started burning waste in 1987, they have had ‘allowable emissions’ of extremely toxic chemicals, such as PCB’s, dioxins, and furans, which are released in small, but continuous amounts through their smokestacks into the environment. Over decades, this adds up to a large amount toxic particulate matter into the atmosphere. Serious “unplanned releases” occurred during fires and explosions in at least 1996, 1997, and 2009, releasing large amounts of toxins into the air. -

Legend - AUPE Area Councils Whiskey Gap Del Bonita Coutts

Indian Cabins Steen River Peace Point Meander River 35 Carlson Landing Sweet Grass Landing Habay Fort Chipewyan 58 Quatre Fourches High Level Rocky Lane Rainbow Lake Fox Lake Embarras Portage #1 North Vermilion Settlemen Little Red River Jackfish Fort Vermilion Vermilion Chutes Fitzgerald Embarras Paddle Prairie Hay Camp Carcajou Bitumount 35 Garden Creek Little Fishery Fort Mackay Fifth Meridian Hotchkiss Mildred Lake Notikewin Chipewyan Lake Manning North Star Chipewyan Lake Deadwood Fort McMurray Peerless Lake #16 Clear Prairie Dixonville Loon Lake Red Earth Creek Trout Lake #2 Anzac Royce Hines Creek Peace River Cherry Point Grimshaw Gage 2 58 Brownvale Harmon Valley Highland Park 49 Reno Blueberry Mountain Springburn Atikameg Wabasca-desmarais Bonanza Fairview Jean Cote Gordondale Gift Lake Bay Tree #3 Tangent Rycroft Wanham Eaglesham Girouxville Spirit River Mclennan Prestville Watino Donnelly Silverwood Conklin Kathleen Woking Guy Kenzie Demmitt Valhalla Centre Webster 2A Triangle High Prairie #4 63 Canyon Creek 2 La Glace Sexsmith Enilda Joussard Lymburn Hythe 2 Faust Albright Clairmont 49 Slave Lake #7 Calling Lake Beaverlodge 43 Saulteaux Spurfield Wandering River Bezanson Debolt Wembley Crooked Creek Sunset House 2 Smith Breynat Hondo Amesbury Elmworth Grande Calais Ranch 33 Prairie Valleyview #5 Chisholm 2 #10 #11 Grassland Plamondon 43 Athabasca Atmore 55 #6 Little Smoky Lac La Biche Swan Hills Flatbush Hylo #12 Colinton Boyle Fawcett Meanook Cold Rich Lake Regional Ofces Jarvie Perryvale 33 2 36 Lake Fox Creek 32 Grand Centre Rochester 63 Fort Assiniboine Dapp Peace River Two Creeks Tawatinaw St. Lina Ardmore #9 Pibroch Nestow Abee Mallaig Glendon Windfall Tiger Lily Thorhild Whitecourt #8 Clyde Spedden Grande Prairie Westlock Waskatenau Bellis Vilna Bonnyville #13 Barrhead Ashmont St. -

Education, Training and Cooperation with Other Agencies

SECTION ELEVEN EDUCATION, TRAINING AND COOPERATION WITH OTHER AGENCIES 11 Education, Training and Cooperation with Other Agencies Blue Ridge Lumber is very pro-active in supporting various education and training programs for the surrounding community schools, provincial post secondary forestry facilities, open houses and local stakeholder groups, contractors and their employees and the owners of private timber. The Company’s focus for local support of education has been the presentations of sustainable forestry practices by various woods staff at the local grade schools. Some of the woods staff has also been involved with the Junior Forest Warden Program that educates pre-teens to sustainable forestry practices. Over the past few years, the Company has also supported various forestry tours of the FMA area by the local area’s Chamber of Commerce and Agriculture Society’s. Blue Ridge Lumber has provided classroom lectures and tours of harvesting, silviculture operations and manufacturing facilities to both forestry programs from the University of Alberta (U of A) and the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT). The Company annually supports the U of A Forest Industry Lecture Series. This Lecture series brings forest industry leaders to the U of A to make presentation to the students and faculties members on various forest research and innovative programs. Blue Ridge Lumber also supports the NAIT Forestry Program by assisting the first year forestry program at the Kidney Lake Fall Camp, which is located within our FMA area. Blue Ridge Lumber assists the NAIT Forestry Program by providing seedlings for planting, and areas for spacing and cleaning, and for regeneration surveys.