Ed 370 413 Author Title Institution Pub Date Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bannock: a Brief History

Bannock: A brief history cbc.ca/radio/unreserved/bannock-wild-meat-and-indigenous-food-sovereignty-1.3424436/bannock-a-brief-history-1.3425549 The Inuit call it 'palauga,' it's 'luskinikn' to the Mi'kmaq, while the Ojibway call it 'ba`wezhiganag.' Whatever they call it, from north to south and coast to coast, just about every indigenous nation across North America has some version of bannock. CBC Radio · June 20 Light, fluffy and golden brown fried bannock is sometimes called frybread. (Tim Fontaine) The Inuit call it 'palauga,' it's 'luskinikn' to the Mi'kmaq, while the Ojibway call it 'ba`wezhiganag.' Whatever they call it, from north to south and coast to coast, just about every Indigenous nation across North America has some version of bannock. Most Indigenous families have their own unique recipes, which are passed down from generation to generation. Yet few, it seems, know where bannock came from. Origins of modern bannock Modern bannock, heavy and dense when baked — or light, fluffy and golden brown when fried — is usually made from wheat flour, which was introduced by Europeans, particularly Scots, who had their own flat cakes of unleavened barley or oatmeal dough called bannock. But Nancy Turner, a professor of environmental studies at the University of Victoria, says Indigenous people already had their own version made from a wild plant called camas. Professional bannock makers at Neechi Commons in Winnipeg will prepare up to 100 bannock loaves each day .(Tim Fontaine)The camasbulb would have been baked for long periods of time, dried and then flattened or chopped and formed into cakes and loaves, similar to modern bannock. -

Festiwal Chlebów Świata, 21-23. Marca 2014 Roku

FESTIWAL CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA, 21-23. MARCA 2014 ROKU Stowarzyszenie Polskich Mediów, Warszawska Izba Turystyki wraz z Zespołem Szkół nr 11 im. Władysława Grabskiego w Warszawie realizuje projekt FESTIWAL CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA 21 - 23 marca 2014 r. Celem tej inicjatywy jest promocja chleba, pokazania jego powszechności, ale i równocześnie różnorodności. Zaplanowaliśmy, że będzie się ona składała się z dwóch segmentów: pierwszy to prezentacja wypieków pieczywa według receptur kultywowanych w różnych częściach świata, drugi to ekspozycja producentów pieczywa oraz związanych z piekarnictwem produktów. Do udziału w żywej prezentacji chlebów świata zaprosiliśmy: Casa Artusi (Dom Ojca Kuchni Włoskiej) z prezentacją piady, producenci pity, macy oraz opłatka wigilijnego, Muzeum Żywego Piernika w Toruniu, Muzeum Rolnictwa w Ciechanowcu z wypiekiem chleba na zakwasie, przedstawiciele ambasad ze wszystkich kontynentów z pokazem własnej tradycji wypieku chleba. Dodatkowym atutem będzie prezentacja chleba astronautów wraz osobistym świadectwem Polskiego Kosmonauty Mirosława Hermaszewskiego. Nie zabraknie też pokazu rodzajów ziarna oraz mąki. Realizacją projektu będzie bezprecedensowa ekspozycja chlebów świata, pozwalająca poznać nie tylko dzieje chleba, ale też wszelkie jego odmiany występujące w różnych regionach świata. Taka prezentacja to podkreślenie uniwersalnego charakteru chleba jako pożywienia, który w znanej czy nieznanej nam dotychczas innej formie można znaleźć w każdym zakątku kuli ziemskiej zamieszkałym przez ludzi. Odkąd istnieje pismo, wzmiankowano na temat chleba, toteż, dodatkowo, jego kultowa i kulturowo – symboliczna wartość jest nie do przecenienia. Inauguracja FESTIWALU CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA planowana jest w piątek, w dniu 21 marca 2014 roku, pierwszym dniu wiosny a potrwa ona do niedzieli tj. do 23.03. 2014 r.. Uczniowie wówczas szukają pomysłów na nieodbywanie typowych zajęć lekcyjnych. My proponujemy bardzo celowe „vagari”- zapraszając uczniów wszystkich typów i poziomów szkoły z opiekunami do spotkania się na Festiwalu. -

Improvement of Flat Bread Processing and Properties by Enzymes

Improvement of flatbread processing and quality by enzymes Lutz Popper, Head R & D Flatbread feeds the world Bagebröd, Sweden; Bannock, Scotland; Bolo do caco, Madeira, Portugal; Borlengo, Italy; Farl, Ireland and Scotland; Flatbrød, Norway ; Flatkaka, Iceland; Focaccia, Italy; Ftira, Malta; Lagana, Greece; Lefse, Norway; Lepinja, Croatia, Serbia; Lepyoshka, Russia; Pita, Hungary; Flatbrød, Norway; Podpłomyk, Poland; Pane carasau, Sardinia; Piadina, Italy; Pita, Greece; Pită/Lipie/Turtă, Romania; Pissaladière, France; Pizza, Italy; Podpłomyk, Poland; Posúch, Slovakia; Părlenka, Bulgaria; Rieska, Finland; Somun, Lepina, Bosnia and Herzegovina; Spianata sarda, Sardinia; Staffordshire oatcake, England; Tigella, Italy; Torta, Spain; Torta al testo, Umbria, Italy; Torta de Gazpacho, Spain; Tunnbröd, Sweden; Yemeni lahoh; Barbari, Iran; Bataw, Egypt; Bazlama, Turkey; Gurassa, Sudan; Harsha, Morocco; Khebz, Levant; Khubz, Arabian Peninsula; Lahoh, Northern Somalia, Djibouti, Yemen; Lebanese Bread, Lebanon; Muufo, Somalia; Malooga, Yemen; M'lawi, Tunisia; Chapati, Swahili coast, Uganda; Markook, Levant; Matzo, Israel; Murr, Israel; Pita, Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey and Middle East; Sangak, Iran; Taftan, Iran; Khubz, Arabian Peninsula; Yufka, Dürüm, Turkey; Lavash, Armenia; Matnakash, Armenia; Pogača, Balkans and Turkey; Shotis Puri, Georgia; Tonis Puri, Georgia; Afghan bread or Nan, Afghanistan; Aloo paratha, India and Pakistan; Akki rotti, India; Aparon, Philippines; Bánh, Vietnam; Bakarkhani, Indian subcontinent; Bhatura, Indian subcontinent; -

Now You're Cooking!

(NCL)DRYINGCORNNAVAJO 12 earsfreshcorninhusks Carefullypeelbackhusks,leavingthemattachedatbaseofcorn. cleancorn,removingsilks.Foldhusksbackintoposition.Placeon wirerackinlargeshallowbakingpan.(Allowspacebetweenearsso aircancirculate.)Bakein325degreeovenfor11/2hours.Cool. Stripoffhusks.Hangcorn,soearsdonottouch,inadryplacetill kernelsaredry,atleast7days.Makesabout6cupsshelledcorn. From:ElayaKTsosie,aNativeNavajo.SheteachesNativeAmerican HistoryatattwodifferentNewYorkStateColleges. From:Mignonne Yield:4servings (NCL)REALCANDIEDCORN 222cup frozencornkernels 11/2 cup sugar 111cup water Hereisacandyrecipeforya:)Idon'tletthecorngettoobrown.I insteadtakeitoutwhenit'sanicegoldcolor,drainit,rollitin thesugar,thendryitinaverylowoven150200degrees.Youcan alsodopumpkinthiswaycutinthinstrips.Addhoneyduringthe lastpartofthecookingtogiveitamorenaturaltastebutdon't boilthehoneyasitwillmakeitgooey. Inlargeskillet,combinecorn,1cupofthesugar,andwater.Cook overmediumheat,stirringoccasionallyuntilcornisdeepgoldenin color,about45to60minutes.Drain,thenrollinremainingsugar. Spreadinasinglelayeronbakingsheetandcool.Storeinatightly sealedcontainerorbag.Useastoppingsforicecream,inpuddings, custards,offillings,orasasubstitutefornutsinbaking.Ohgood rightoutofthebagtoo! From:AnnNelson Yield:4servings Page 222 (NCL)SHAWNEERECIPEFORDRYINGCORN 111corn Selectcornthatisfirmbutnothard.Scrapeoffofcobintodeep pan.Whenpanisfull,setinslowovenandbakeuntilthoroughly heatedthrough,anhourormore.Removefromovenandturnponeout tocool.Latercrumbleondryingboardinthesunandwhenthoroughly -

Kitchen Math Workbook Series

Kitchen Math Everyday Math Skills | 2009 NWT Literacy Council 114648 Kitchen Math cover.indd 1 11/6/09 12:10:12 PM Acknowledgements The NWT Literacy Council gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance for this project from the Department of Education, Culture and Employment, GNWT. Lisa Campbell did the research and writing for this workbook. We would like to thank Joyce Gilchrist for editing and reviewing this resource. Contact the NWT Literacy Council to get copies of the Kitchen Math Workbook. Or you can download it from our website. NWT Literacy Council Box 761, Yellowknife, NT X1A 2N6 Phone toll free: 1-866-599-6758 Phone Yellowknife: (867) 873-9262 Fax: (867) 873-2176 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nwt.literacy.ca Kitchen Math Workbook Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................. Page 3-4 Section One: Shopping for the Kitchen................................................... Page 5 The Food Budget #1........................................................................... Page 6 The Shopping List #2......................................................................... Page 7-8 More on Shopping Lists #3............................................................... Page 9-10 Estimating Your Groceries #4.......................................................... Page 11-12 Using Coupons #5.............................................................................. Page 13-14 Planning for Snacks for an Event -

Imaginative Curriculum Design

Topic: The History and Diversity of Bread Around the World Target Grade Level: 11 Subject Area: Home Economics: Foods & Nutrition Planning Framework: Romantic Unit Length: 2 -3 weeks Author: Marianne Honeywell Romantic Framework 1. Identifying “heroic” qualities: Main heroic quality: Diversity There are thousands of different kinds of bread eaten by almost every culture around the world. Adaptability In each region of the world, bread has traditionally been made from the grains native to that area. Alternative(s): Life Giving Bread and grain products provide our bodies with an important source of energy and carbohydrates. They comprise the largest part of most of the world’s food source. Ingenuity The simple, yet complex process of making a loaf of bread Images that capture the heroic qualities: Bread is eaten all over the world by almost every culture. If we traveled to the other side of the planet we would probably find a culture very different from our own, yet with its own version of bread. The diversity of this staple food is endless and every culture prides itself in having its own unique kind of bread. If we went on an international culinary bread tour, we could eat baguettes from France, focaccia from Italy, soda bread in Ireland, naan and roti from India, dark rye bread in Russia, tortillas in Mexico, pandesal in the Philippines, bannock from North America, or mantou in China (“Bread”, 2010). Almost any variety of grain can be turned into bread, which makes it one of the most diverse foods in the human diet. Breads are formed into endless varieties, shapes, and sizes; with many different flavours and textures. -

Information-Theoretic Causal Inference of Lexical Flow

Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow Johannes Dellert language Language Variation 4 science press Language Variation Editors: John Nerbonne, Martijn Wieling In this series: 1. Côté, Marie-Hélène, Remco Knooihuizen and John Nerbonne (eds.). The future of dialects. 2. Schäfer, Lea. Sprachliche Imitation: Jiddisch in der deutschsprachigen Literatur (18.–20. Jahrhundert). 3. Juskan, Martin. Sound change, priming, salience: Producing and perceiving variation in Liverpool English. 4. Dellert, Johannes. Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow. ISSN: 2366-7818 Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow Johannes Dellert language science press Dellert, Johannes. 2019. Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow (Language Variation 4). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/233 © 2019, Johannes Dellert Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-96110-143-6 (Digital) 978-3-96110-144-3 (Hardcover) ISSN: 2366-7818 DOI:10.5281/zenodo.3247415 Source code available from www.github.com/langsci/233 Collaborative reading: paperhive.org/documents/remote?type=langsci&id=233 Cover and concept of design: Ulrike Harbort Typesetting: Johannes Dellert Proofreading: Amir Ghorbanpour, Aniefon Daniel, Barend Beekhuizen, David Lukeš, Gereon Kaiping, Jeroen van de Weijer, Fonts: Linux Libertine, Libertinus Math, Arimo, DejaVu Sans Mono Typesetting software:Ǝ X LATEX Language Science Press Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin, Germany langsci-press.org Storage and cataloguing done by FU Berlin Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Foundations: Historical linguistics 7 2.1 Language relationship and family trees ............. -

Breads & Cereals

BREADS & CEREALS LEADERS’ RESOURCE MANUAL The 4-H Motto “Learn to do by Doing” The 4-H Pledge I pledge My Head to clearer thinking, My Heart to greater loyalty, My Hands to larger service, My Health to better living, For my club, my community, and my country. The 4-H Grace (Tune of Auld Lang Syne) We thank thee, Lord, for blessings great on this, our own fair land. Teach us to serve thee joyfully, with head, heart, health and hand. Published by: Canadian 4-H Council Resource Network, Ottawa ON Compiled by: Andrea Lewis, Manitoba Graphic Design by: Perpetual Notion, www.perpetualnotion.ca Date: April 2008 2 Welcome to Food and You - Breads and Cereals Members and leaders will be using the eight page member project guide as in past years. A copy of the Member’s Guide for Food and You 4 is included in this resource book. This resource guide includes: Lesson Information Suggested activities to assist with learning Suggested recipes Food and You 4 contains information on four basic areas: Eating Well Cook it Well Fundamentals Field to Fork This project will focus on Breads and Cereals. In each lesson segment, there are suggested activities and recipes to accompany the foods information. To finish the project, members are required to complete 6 to 8 meetings or lessons. Be sure to spend at least one lesson with the members making pan rolls which are one of the project requirements for Food and You - Breads and Cereals. Hope you enjoy your year as a 4-H Foods leader! ACHIEVEMENT DAY REQUIREMENTS Pan Rolls (4) 50 Recipe File (containing at least 8 grain product recipes 25 plus a picture of the member showing at least one recipe Encourage members to consider at least one special needs diet recipe, i.e. -

Information-Theoretic Causal Inference of Lexical Flow

Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow Johannes Dellert language Language Variation 4 science press Language Variation Editors: John Nerbonne, Martijn Wieling In this series: 1. Côté, Marie-Hélène, Remco Knooihuizen and John Nerbonne (eds.). The future of dialects. 2. Schäfer, Lea. Sprachliche Imitation: Jiddisch in der deutschsprachigen Literatur (18.–20. Jahrhundert). 3. Juskan, Martin. Sound change, priming, salience: Producing and perceiving variation in Liverpool English. 4. Dellert, Johannes. Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow. ISSN: 2366-7818 Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow Johannes Dellert language science press Dellert, Johannes. 2019. Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow (Language Variation 4). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/233 © 2019, Johannes Dellert Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-96110-143-6 (Digital) 978-3-96110-144-3 (Hardcover) ISSN: 2366-7818 DOI:10.5281/zenodo.3247415 Source code available from www.github.com/langsci/233 Collaborative reading: paperhive.org/documents/remote?type=langsci&id=233 Cover and concept of design: Ulrike Harbort Typesetting: Johannes Dellert Proofreading: Amir Ghorbanpour, Aniefon Daniel, Barend Beekhuizen, David Lukeš, Gereon Kaiping, Jeroen van de Weijer, Fonts: Linux Libertine, Libertinus Math, Arimo, DejaVu Sans Mono Typesetting software:Ǝ X LATEX Language Science Press Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin, Germany langsci-press.org Storage and cataloguing done by FU Berlin Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Foundations: Historical linguistics 7 2.1 Language relationship and family trees ............. -

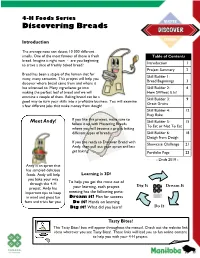

Discovering Breads

4-H Foods Series Discovering Breads Introduction The average nose can detect 10 000 different smells. One of the most famous of those is fresh Table of Contents bread. Imagine it right now - are you beginning Introduction 1 to crave a slice of freshly baked bread? Project Summary 2 Bread has been a staple of the human diet for Skill Builder 1: many, many centuries. This project will help you Bread Beginnings 3 discover where bread came from and where it has advanced to. Many ingredients go into Skill Builder 2: 6 making the perfect loaf of bread and we will How SWheat It Is! examine a couple of them. Baking bread can be a Skill Builder 3: 9 good way to turn your skills into a profitable business. You will examine Great Grains a few different jobs that make money from dough! Skill Builder 4: 12 Easy Bake If you like this project, make sure to Meet Andy! Skill Builder 5: 15 follow it up with Mastering Breads To Eat or Not To Eat where you will become a pro at baking different types of breads. Skill Builder 6: 18 Dough from Dough If you are ready to Discover Bread with Showcase Challenge 21 Andy, then pull out your apron and lets get baking! Portfolio Page 23 - Draft 2019 - Andy is an apron that has sampled delicious foods. Andy will help Learning is 3D! you bake your way To help you get the most out of through this 4-H Dig It Dream It project. Andy has your learning, each project important tips to keep meeting has the following parts: in mind and great fun Dream it! Plan for success facts and trivia for you. -

Bannock Awareness

Bannock Awareness Printed In Celebration of Aboriginal Awareness Day June 21, 2013 Also see our website: http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/rsi/fnb/fnb.htm Bannock Awareness Also see our website: Original Print 2001 Printed In Celebration of http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/rsi/fnb/fnb.htm Aboriginal Awareness Day June 21 Graphics Courtesy of Michael Blackstock Index to Recipes Navajo Fry Bread (Bannock) ............................................................................... 10 Bonnie Harvey's 321 Fry Bread........................................................................... 10 Indian Taco .......................................................................................................... 12 Bella Coola Bannock Recipe ............................................................................... 12 Basic Bannock Recipe ......................................................................................... 16 Shuswap Bannock ................................................................................................ 18 Secwepemc Lichen Bannock. ............................................................................. 18 Sunflower Bannock .............................................................................................. 20 Tsaibesa's Bannock.............................................................................................. 20 White Woman Bannock! ...................................................................................... 22 Indian Bread “Little yeast breads” ...................................................................... -

Priest Flies to Rangely Mass German Priests

T T > rrr t : Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations ABBOT TELLS OAOHAU HOBROR Priest Flies to Rangely Mass German Priests Contents CopTrighted by the Catholic Press Society, Ind. 1946— Permission to reproduce, Except on Heroic in Fight ‘PICIiE Benedictine Pilots Articles Otherwise Marked, given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue Plane Every Sunday DENVERCATHOLICl**” "** [I CIBmill Center in Utah Rt. Rev. Corbinian Hofmeister, A portrait of S t Frances Xav Fr. Blase Schumacher Only Padre in Two Former Gestapo Prisoner, ier Cabrini holds the place of honor States Who Takes to A ir for Paro amoni; 130 oil paintings of the Denver Visitor famous and colorful citizens of chial Work The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We Have Also the International News Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller Denver and Colorado that decorate The sometimes impassable roads leading to the mushrooming oil By Rev. John B. Ebel the walls of a room in the home Services, Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. (3 cents per copy) o f Mr. and Mrs. Fred Mazzulla of town of Rangely, Colo., are no problem to dbe Rev. Blase Schumacher, Arrested by the Gestapo twice, imprisoned in the dank Denver. The paintin|;s are the O.S.B., of Vernal, Utah, who cares for the Qtholics of the Rangely VOL. XUI. No. 10. d e n v A i , COLO., THURSDAY, OCTOBER 31, 1946. f 1 PER YEAR. Gestapo dungeons of Berlin in solitary confinement for a work of Herndon Davis. vicinity; for he is the "flying priest” of Colorado and Utah.