MOES SC501 1 Running Head

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nonpubenrollment2014-15 INST CD 010100115658 010100115665 010100115671 010100115684 010100115685 010100115705 010100115724 01010

Nonpubenrollment2014-15 INST_CD 010100115658 010100115665 010100115671 010100115684 010100115685 010100115705 010100115724 010100118044 010100208496 010100317828 010100996053 010100996179 010100996428 010100996557 010100997616 010100997791 010100997850 010201805052 010306115761 010306809859 010306999575 010500996017 010601115674 010601216559 010601315801 010601629639 010623115655 010623115753 010623116561 010623806562 010623995677 010802115707 020801659054 021601658896 022001807067 022601136563 030200185471 030200185488 030200227054 030701998080 030701998858 031401996149 031501187966 031502185486 031502995612 031601806564 042400136448 042400139126 042400805651 042901858658 043001658554 Page 1 Nonpubenrollment2014-15 043001658555 043001658557 043001658559 043001658561 043001658933 043001659682 050100169701 050100996140 050100996169 050100999499 050100999591 050301999417 050701999254 051101658562 051101658563 051901425832 051901427119 060201858116 060503658575 060503659689 060601658556 060601659292 060601659293 060601659294 060601659295 060601659296 060601659297 060601659681 060701655117 060701656109 060701659831 060701659832 060800139173 060800808602 061700308038 062601658578 062601658579 062601659163 070600166199 070600166568 070600807659 070901166200 070901855968 070901858020 070901999027 081200185526 081200808719 091101159175 091101858426 091200155496 091200808631 100501997955 Page 2 Nonpubenrollment2014-15 101601996549 101601998246 110200185503 110200808583 110200809373 120501999934 120906999098 121901999609 130200805048 130200809895 -

Illinois Tech Contract Usage 2019-2020

Illinois Technology Contract Usage 2019-2020 MHEC CONTRACTS leverage the potential volume of back to the institutions. Additionally, because of MHEC’s the region’s purchasing power while saving institutions statutory status, many of these contracts can also be time and money by simplifying the procUrement process. adopted for use by K-12 districts and schools, as well as The2 contracts0182019 provide competitive solutions established cities, states, and local governments. An added benefit in accordance with public procurement laws thereby for smaller institutions is that these contracts allow these negating the institution’s need to conduct a competitive institutions to negotiate from the same pricing and terms sourcing event. By offering a ready-to-use solution with normally reserved for larger institutions. MHEC relies on theANNUAL ability to tailor the already negotiated contract to institutional experts to participate in the negotiations, match the institution’s specific needs and requirements, sharing strategies and tactics on dealing with specific MHECREPORT contracts shift some of the negotiating power contractual issues and vendors. HARDWARE CONTRACTS Illinois College of Optometry McHenry County College Rock Valley College Higherto theEducation MemberIllinois Community States College Midwestern University Rockford University Board Aurora University Monmouth College Roosevelt University Illinois Eastern Community Benedictine University Moraine Valley Community Rosalind Franklin University of Colleges College Medicine and Science -

2011 Annual Report

فََسََيى اللَّ ُه َعَملَ ُك ْم َوَر ُسولُ ُه َوالْ ُم ْؤ ِم ُنَون 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 03 VISION STATEMENT , MISSION STATEMENT 04 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 05 RELIGIOUS SERVICES 06 EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS 07 CHARITABLE AND ZAKAT PROGRAMS 08,09 COMMUNITY SERVICES 10 COMMUNITY OUTREACH 11 INTERFAITH INITIATIVES 12,13 COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIP 14,17 EVENTS AT MOSQUE FOUNDATION IN 2011 18,19 MOSQUE FOUNDATION COMMUNITY CENTER 2011 REPORT 20 AL-SIDDIQ WEEKEND SCHOOL REPORT OF 2011 21 QURAN SUMMER PROGRAM REPORT OF 2011 22 THE MOSQUE FOUNDATION’S FOOD PANTRY REPORT OF 2011 22,23 WOMEN’S ROLE AT THE MOSQUE FOUNDATION 2011 REPORT 24,25 FINANCIAL REPORT 26,27 MEET THE PEOPLE BEHIND OUR ORGANIZATION 28,29 BOARD & FUNCTIONAL COMMITTEES VISION STATEMENT Our vision is to be the leading mosque in the United States in providing Islamic guidance and services to the community. MISSION STATEMENT The Mosque Foundation serves the spiritual, religious, and communal needs of area Muslims by means of nurturing their faith, upholding their values, and foster- ing the wellbeing of the community around us through worship, charity, education, outreach, and civic engagement. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Assalamu Alaikum, We would like to thank you greatly for your continuous involvement and gener- ous support of your second home: the Mosque Foundation. The year 2011 was a remarkable year that we enjoyed the blessing of larger facilities and expanded programs and activities. proactive program developed and led by youth themselves under the supervision As one of the most prominent mosques in Illinois, the Mosque Foundation has of our Imams. Several in-depth workshops were held such as Successful Mar- established itself as a forerunner of progress and development in the American riage, Healthy Family & Parenting, Hajj, Property Tax Appeal and others. -

To Lead and Inspire Philanthropic Efforts That Measurably Improve the Quality of Life and the Prosperity of Our Region

2008 ANNUAL REPORT To lead and inspire philanthropic efforts that measurably improve the quality of life and the prosperity of our region. OUR VALUES Five values define our promise to the individuals and communities we serve: INTEGRITY Our responsibility, first and foremost, is to uphold the public trust placed in us and to ensure that we emulate the highest ethical standards, honor our commitments, remain objective and transparent and respect all of our stakeholders. STEWARDSHIP & SERVICE We endeavor to provide the highest level of service and due diligence to our donors and grant recipients and to safeguard donor intent in perpetuity. DIVERSITY & INCLUSION Our strength is found in our differences and we strive to integrate diversity in all that we do. COLLABORATION We value the transformative power of partnerships based on mutual interests, trust and respect and we work in concert with those who are similarly dedicated to improving our community. INNOVATION We seek and stimulate new approaches to address what matters most to the people and we serve, as well as support, others who do likewise in our shared commitment to improve metropolitan Chicago. OUR VISION The Chicago Community Trust is committed to: • Maximizing our community and donor impact through strategic grant making and bold leadership; • Accelerating our asset growth by attracting new donors and creating a closer relationship with existing donors; • Delivering operational excellence to our donors, grant recipients and staff members. In 2008, The Chicago Community Trust addressed the foreclosure crisis by spearheading an action plan with over 100 experts from 70 nonprofit, private and public organizations. -

Harnessing the Power of Faith: Serving Humanity Co-Sponsored by Aldeen Foundation

Harnessing the Power of Faith: Serving Humanity Co-sponsored by Aldeen Foundation Friday Workshops I. Curriculum and Instruction ASCD Pam Robbins Social Emotional Learning (SEL) is the “missing piece” in the quest to provide effective education for all children, young people, and adults. It has been shown to have a positive 10:30-6:45 effect in enhancing student achievement and is an important resource in reducing or eliminating risky behaviors. SEL interventions produce positive attitudinal and behavioral effects. Research documents that focusing on SEL results in improvements in academic performance, SEL skills, pro-social behaviors, self-esteem, bonding to school, and reductions in conduct problems and emotional distress. This session will examine what SEL is, the critical role it plays in student and school success, five domains of SEL competence, and will offer specific strategies to develop and implement Social Emotional Competence in ways that contribute to positive classroom climate and student success. Session 1 - Social Emotional Learning Session 2 - Examining the Elements of Social Emotional Learning Session 3 - Managing Emotions Session 4 - Handling Relationships Session 5 - Creating Classroom Cultures that Reflect Social Emotional Learning Pam Robbins is an independent educational consultant who works with public and private schools, state departments of education, professional organizations and associations throughout the United States and Internationally. Pam’s professional interests include Social-Emotional Learning, Peer Coaching, mentoring, brain research and effective teaching, learning communities, leadership, supervision, the leadership practices of Abraham Lincoln, and presentation skills. As an educator, Pam’s experience includes serving as a special education teacher, intermediate grades classroom teacher, high school basketball coach, and school leader. -

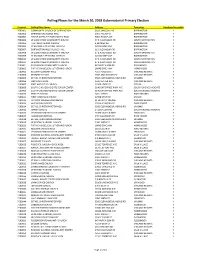

Polling Place List

Polling Places for the March 20, 2018 Gubernatorial Primary Election Precinct Polling Place Name Address Township Handicap Accessible 7000001 COMMUNITY CHURCH OF BARRINGTON 301 E LINCOLN AVE BARRINGTON Y 7000002 BARRINGTON VILLAGE HALL 200 S HOUGH ST BARRINGTON Y 7000003 GROVE AVENUE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 900 S GROVE AVE BARRINGTON Y 7000004 WILLOW CREEK COMMUNITY CHURCH 67 E ALGONQUIN RD SOUTH BARRINGTON Y 7000005 THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH 6 BRINKER RD BARRINGTON Y 7000006 ST MICHAELS EPISCOPAL CHURCH 647 DUNDEE AVE BARRINGTON Y 7000007 BARRINGTON HILLS VILLAGE HALL 112 ALGONQUIN RD BARRINGTON Y 7000008 WILLOW CREEK COMMUNITY CHURCH 67 E ALGONQUIN RD SOUTH BARRINGTON Y 7000009 ST MICHAELS EPISCOPAL CHURCH 647 DUNDEE AVE BARRINGTON Y 7000010 WILLOW CREEK COMMUNITY CHURCH 67 E ALGONQUIN RD SOUTH BARRINGTON Y 7000011 WILLOW CREEK COMMUNITY CHURCH 67 E ALGONQUIN RD SOUTH BARRINGTON Y 7100001 FLOSSMOOR COMMUNITY CHURCH 847 HUTCHISON RD FLOSSMOOR Y 7100002 FAITH EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH 18645 DIXIE HWY HOMEWOOD Y 7100003 BLOOM TOWNSHIP HALL 425 S HALSTED ST CHICAGO HEIGHTS Y 7100004 KENNEDY SCHOOL 10TH AND DIVISION ST CHICAGO HEIGHTS Y 7100005 BETHEL CHRISTIAN REFORMED 3500 GLENWOOD/LANSING RD LANSING Y 7100006 LINCOLN SCHOOL 1520 CENTER AVE CHICAGO HEIGHTS Y 7100007 FIRST APOSTOLIC CHURCH 22709 STATE ST STEGER Y 7100008 SOUTH CHICAGO HEIGHTS SENIOR CENTER 3140 ENTERPRISE PARK AVE SOUTH CHICAGO HEIGHTS Y 7100009 SOUTH CHICAGO HEIGHTS SENIOR CENTER 3140 ENTERPRISE PARK AVE SOUTH CHICAGO HEIGHTS Y 7100010 PHILLIPS SCHOOL 1401 13TH PL FORD HEIGHTS -

Secondary School/ Community College Code List 2014–15

Secondary School/ Community College Code List 2014–15 The numbers in this code list are used by both the College Board® and ACT® connect to college successTM www.collegeboard.com Alabama - United States Code School Name & Address Alabama 010000 ABBEVILLE HIGH SCHOOL, 411 GRABALL CUTOFF, ABBEVILLE AL 36310-2073 010001 ABBEVILLE CHRISTIAN ACADEMY, PO BOX 9, ABBEVILLE AL 36310-0009 010040 WOODLAND WEST CHRISTIAN SCHOOL, 3717 OLD JASPER HWY, PO BOX 190, ADAMSVILLE AL 35005 010375 MINOR HIGH SCHOOL, 2285 MINOR PKWY, ADAMSVILLE AL 35005-2532 010010 ADDISON HIGH SCHOOL, 151 SCHOOL DRIVE, PO BOX 240, ADDISON AL 35540 010017 AKRON COMMUNITY SCHOOL EAST, PO BOX 38, AKRON AL 35441-0038 010022 KINGWOOD CHRISTIAN SCHOOL, 1351 ROYALTY DR, ALABASTER AL 35007-3035 010026 EVANGEL CHRISTIAN SCHOOL, PO BOX 1670, ALABASTER AL 35007-2066 010028 EVANGEL CLASSICAL CHRISTIAN, 423 THOMPSON RD, ALABASTER AL 35007-2066 012485 THOMPSON HIGH SCHOOL, 100 WARRIOR DR, ALABASTER AL 35007-8700 010025 ALBERTVILLE HIGH SCHOOL, 402 EAST MCCORD AVE, ALBERTVILLE AL 35950 010027 ASBURY HIGH SCHOOL, 1990 ASBURY RD, ALBERTVILLE AL 35951-6040 010030 MARSHALL CHRISTIAN ACADEMY, 1631 BRASHERS CHAPEL RD, ALBERTVILLE AL 35951-3511 010035 BENJAMIN RUSSELL HIGH SCHOOL, 225 HEARD BLVD, ALEXANDER CITY AL 35011-2702 010047 LAUREL HIGH SCHOOL, LAUREL STREET, ALEXANDER CITY AL 35010 010051 VICTORY BAPTIST ACADEMY, 210 SOUTH ROAD, ALEXANDER CITY AL 35010 010055 ALEXANDRIA HIGH SCHOOL, PO BOX 180, ALEXANDRIA AL 36250-0180 010060 ALICEVILLE HIGH SCHOOL, 417 3RD STREET SE, ALICEVILLE AL 35442 -

TC Code Institution City State 001370 UNIV of ALASKA ANCHORAGE ANCHORAGE AK 223160 KENNY LAKE SCHOOL COPPER CENTER AK 161760

TC Code Institution City State 001370 UNIV OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE ANCHORAGE AK 223160 KENNY LAKE SCHOOL COPPER CENTER AK 161760 GLENNALLEN HIGH SCHOOL GLENNALLEN AK 217150 HAINES HIGH SCHOOL HAINES AK 170350 KETCHIKAN HIGH SCHOOL KETCHIKAN AK 000690 KENAI PENINSULA COLLEGE SOLDOTNA AK 000010 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMMUNITY COLLEGE ALEXANDER CITY AL 000810 LURLEEN B WALLACE COMM COLLEGE ANDALUSIA AL 232220 ANNISTON HIGH SCHOOL ANNISTON AL 195380 ATHENS HIGH SCHOOL ATHENS AL 200490 AUBURN HIGH SCHOOL AUBURN AL 000350 COASTAL ALABAMA COMMUNITY COLLEGE BAY MINETTE AL 000470 JEFFERSON STATE C C - CARSON RD BIRMINGHAM AL 000560 UNIV OF ALABAMA AT BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM AL 158980 CARVER HIGH SCHOOL BIRMINGHAM AL 159110 WOODLAWN HIGH SCHOOL BIRMINGHAM AL 162830 HUFFMAN HIGH SCHOOL BIRMINGHAM AL 224680 SHADES VALLEY HIGH SCHOOL BIRMINGHAM AL 241320 RAMSAY HIGH SCHOOL BIRMINGHAM AL 000390 COASTAL ALABAMA COMMUNITY COLLEGE BREWTON AL 170150 WILCOX CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL CAMDEN AL 227610 MACON EAST MONTGOMERY ACADEMY CECIL AL 207960 BARBOUR COUNTY HIGH SCHOOL CLAYTON AL 230850 CLEVELAND HIGH SCHOOL CLEVELAND AL 165770 DADEVILLE HIGH SCHOOL DADEVILLE AL 163730 DAPHNE HIGH SCHOOL DAPHNE AL 170020 DECATUR HIGH SCHOOL DECATUR AL 163590 NORTHVIEW HIGH SCHOOL DOTHAN AL 170030 DOTHAN PREPARATORY ACADEMY DOTHAN AL 203600 ELMORE COUNTY HIGH SCHOOL ECLECTIC AL 213060 ELBA HIGH SCHOOL ELBA AL 000450 ENTERPRISE STATE COMM COLLEGE ENTERPRISE AL 170100 EUFAULA HIGH SCHOOL EUFAULA AL 166720 FAIRHOPE HIGH SCHOOL FAIRHOPE AL 000800 BEVILL STATE C C - BREWER CAMPUS FAYETTE AL 000140 -

2017 Marquette Bank Organizations

Neighborhood Coat Drive St. Blasé Dinner Volunteers Blessing Bags Project Feed My Lambs Lunch Project Easter Baskets Project Port Ministries Lunch Truck Mooseheart Volunteers Food Depository Volunteers Pancreatic Cancer Fundraiser Meals from the Heart Volunteers Neighborhood School Supply Drive Annual Neighborhood Food Drive In 2017, Marquette Bank helped over 180 neighborhood organizations, like these: Accion Chicago Chicago Southland Chamber of Commerce Little Village Lawndale High School Romeoville High School Action Coalition of Englewood Children’s Research Fund Lockport Police Ronald McDonald House Advocate Charitable Fund Cook County Sheriff’s Police March of Dimes Running For Hope Association Advocate Hope Children’s Hospital Crisis Center For South Suburbia Marist High School Rush University Medical Center Air Force Academy High School Cristo Rey Jesuit High School Metropolitan Alliance of Police - Oak Forest Chapter Saint Ignatius College Prep Almost Home Chicago Curie Metropolitan High School Metropolitan Family Services Sandburg High School Alzheimer’s Association, Illinois De La Salle Institute Misericordia Home Shady Oaks Camp American Cancer Society Easter Seals Metropolitan Chicago Mokena’s Festa Italiano Shepard High School American Legion Post #800 Eisenhower High School Monroe Foundation Simeon Career Academy American Red Cross Englewood Back To School Montessori School of Lemont South Suburban Association Chiefs of Police Andrew High School Eric Solorio Academy High School Morgan Park High School South Suburban PADS Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital Evening Star M.B. Church Morgan Park Junior Women’s Club Southside Irish Parade Aqsa School Evergreen Park Firefighters Association Mother McAuley Liberal Arts High School Southwest Home Equity Assurance Program Argo Community High School Evergreen Park High School Mt. -

Funding Year 2010 Authorizations – 4Q2011

Universal Service Administrative Company Appendix SL30 Schools and Libraries 2Q2012 Funding Year 2010 Authorizations - 4Q2011 Page 1 of 196 Applicant Name City State Authorized 21ST CENTURY CHARTER SCHOOL @ COLORADO COLORADA SPRINGS CO 23,209.60 21ST CENTURY CHARTER SCHOOL @ FOUNTAIN SINDIANAPOLIS IN 13,374.00 21ST CENTURY CHARTER SCHOOL @ GARY GARY IN 55,638.50 21ST. CENTURY CHARTER SCHOOL INDIANAPOLIS IN 21,513.60 A E R O SPECIAL EDUCATION COOP BURBANK IL 12,270.34 A L BROWN HIGH SCHOOL KANNAPOLIS NC 33,994.17 A.C.E. CHARTER HIGH SCHOOL TUCSON AZ 2,844.80 A.W. BROWN FELLOWSHIP CHARTER SCHOOL DALLAS TX 169,806.21 A+ ARTS ACADEMY COLUMBUS OH 3,207.16 AAA ACADEMY POSEN IL 20,715.42 ABBE REGIONAL LIBRARY AIKEN SC 12,388.90 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT ABERDEEN MS 49,402.84 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 5 ABERDEEN WA 921.68 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 6-1 ABERDEEN SD 5,577.37 ABILENE FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY ABILENE KS 10.50 ABILENE INDEP SCHOOL DISTRICT ABILENE TX 216,085.91 ABILENE UNIF SCH DISTRICT 435 ABILENE KS 298.57 ABINGTON HEIGHTS SCHOOL DIST CLARKS SUMMIT PA 28,832.77 ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL SCHOOLS NEW YORK NY 42,286.17 ABRAMS HEBREW ACADEMY YARDLEY PA 242.85 ABRAMSON NEW ORLEANS LA 2,088.03 ABSAROKEE SCHOOL DIST 52-52 C ABSAROKEE MT 617.40 ABSECON PUBLIC LIBRARY ABSECON NJ 598.84 ABYSSINIAN DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION NEW YORK NY 20,978.57 Academia Claret Bayamon PR 2,815.67 ACADEMIA CRISTO DE LOS MILAGROS CAGUAS PR 533.52 ACADEMIA DE LENGUA Y CULTURA ALBUQUERQUE NM 9,409.38 ACADEMIA DEL CARMEN CAROLINA PR 2,650.68 ACADEMIA DEL ESPIRITU SANTO BAYAMON -

Tax Exempt Organizations Awaiting State Payment As of July 12

Tax Exempt Organizations Awaiting State Payment as of July 12 ,2010 Note: The “tax exempt” status reflected in the records is a federal status where “non-for-profit” is a State status (which they do not track in their records). All tax exempt organizations are non-for- profits, but not all non-for-profits are tax exempt. Source: Illinois Office of the Comptroller, Daniel W. Hynes via Freedom of Information Act Request submitted by Heartland Alliance for Human Needs & Human Rights. VENDOR NAME AMT TOTAL $490,314,860.75 100 BLACK MEN OF ALTON INC 10,000.00 1033 AMBULANCE SERVICE LTD 12,123.90 1ST ASSEMBLY OF GOD CHURCH 3,859.89 21ST CENTURY URBAN SCHOOLS 7,041.68 40 NORTH-88 WEST INC 15,300.00 826CHI INC NFP 4,110.00 A KNOCK AT MIDNIGHT NFP 77,846.00 A SILVER LINING FOUNDATION 45,000.00 ABC COUNSELING & FAMILY SVC 25,126.60 ABILITIES PLUS INC 329,215.88 ABOUTABJ COMMUNITY FACE THEATRE SERVICES COLLECTIVE INC 31,483.00 ABRAHAM LINCOLN MEMORIAL 2,840.00 HOSP 25,473.18 ACADEMICABUNDANT DEVELOPMENT NEW LIFE CHURCH 1,548.35 INSTITUTE 77,040.00 ACADEMY FOR URBAN 83,330.00 ACADEMY OF OUR LADY 1,105.68 ACCESS COMMUNITY HEALTH 4,148,064.94 ACCESS LIVINGDUPAGE OF METRO CHICAGO 28,349.10 ACCESS SERVICES OF NORTHERN IL 269,778.73 ACCESSIBLE CONTEMPORARY 300.00 MUSIC 2,530.00 ACHIEVEMENT UNLIMITED INC 2,460,902.37 ACTORS WORKSHOP THEATRE 2,710.00 ADA S MCKINLEY CMNTY SVCS INC 4,230,966.75 ADLERADAMS SCHOOLELECTRIC OF COOPERATIVE PROFESSIONAL 58,328.81 124,958.51 ADULTADOPTIONS AND CHILDUNLIMITED REHAB INC CENTER 142,657.09 ADULTHOOD TRANSITION CENTER -

Seema A. Imam, Ed.D

Seema A. Imam, Ed.D. [email protected] Education Graduate Theological Foundation Mishawaka, IN Doctorate of Education in Islamic Studies and Ministry expected completion 2014 National Louis University Evanston, IL Doctorate of Education in Curriculum and Social Inquiry 2001 Northeastern Illinois University Chicago, IL Master of Arts in Educational Administration and Supervision 1987 Northeastern Illinois University, Chicago, IL Master of Arts in Reading 1983 Northeastern Illinois University Chicago, IL Bachelor of Arts, Elementary and Special Education, Learning Disabilities 1975 Certifications • Superintendent Endorsement • Administrative Type 75 • Learning Disabilities K-12 Type 09 • Reading Specialist K-12 Type 09 • Elementary Teaching K-9 Type 03 Higher Education Experience National Louis University Lisle, Illinois Associate Professor (Tenure 2009) September 2004 – present Assistant Professor September 1996 – 2004 Moraine Valley Community College Palos Hills, Illinois Adjunct Professor September 1996-December 1996 Administrative Experience Northwest Indiana Islamic Center Sunday School Crown Point, Indiana Principal (part-time position) 1995-1998 and 2001-present Avicenna Academy Crown Point, Indiana Superintendent (interim part-time position) 2008-2010 Averroes Academy Northbrook, Illinois Superintendent (interim part-time position) 2003-2004 1 Universal School Bridgeview, Illinois Founding Principal 1990 -1995 Teaching Experience Anderson Academy Chicago, Illinois Teacher, Learning Disabilities 1995-1996 Lyman A. Budlong Elementary