An Antitrust Analysis of Apple's Conduct in the Music Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Peer-To-Peer File Transfer? Bandwidth It Can Use

sharing, with no cap on the amount of commonly used to trade copyrighted music What is Peer-to-Peer file transfer? bandwidth it can use. Thus, a single NSF PC and software. connected to NSF’s LAN with a standard The Recording Industry Association of A peer-to-peer, or “P2P,” file transfer 100Mbps network card could, with KaZaA’s America tracks users of this software and has service allows the user to share computer files default settings, conceivably saturate NSF’s begun initiating lawsuits against individuals through the Internet. Examples of P2P T3 (45Mbps) internet connection. who use P2P systems to steal copyrighted services include KaZaA, Grokster, Gnutella, The KaZaA software assesses the quality of material or to provide copyrighted software to Morpheus, and BearShare. the PC’s internet connection and designates others to download freely. These services are set up to allow users to computers with high-speed connections as search for and download files to their “Supernodes,” meaning that they provide a How does use of these services computers, and to enable users to make files hub between various users, a source of available for others to download from their information about files available on other create security issues at NSF? computers. users’ PCs. This uses much more of the When configuring these services, it is computer’s resources, including bandwidth possible to designate as “shared” not only the and processing capability. How do these services function? one folder KaZaA sets up by default, but also The free version of KaZaA is supported by the entire contents of the user’s computer as Peer to peer file transfer services are highly advertising, which appears on the user well as any NSF network drives to which the decentralized, creating a network of linked interface of the program and also causes pop- user has access, to be searchable and users. -

Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture | the AHRC Cultural Value

Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska 2 Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska THE AHRC CULTURAL VALUE PROJECT CONTENTS Foreword 3 4. The engaged citizen: civic agency 58 & civic engagement Executive summary 6 Preconditions for political engagement 59 Civic space and civic engagement: three case studies 61 Part 1 Introduction Creative challenge: cultural industries, digging 63 and climate change 1. Rethinking the terms of the cultural 12 Culture, conflict and post-conflict: 66 value debate a double-edged sword? The Cultural Value Project 12 Culture and art: a brief intellectual history 14 5. Communities, Regeneration and Space 71 Cultural policy and the many lives of cultural value 16 Place, identity and public art 71 Beyond dichotomies: the view from 19 Urban regeneration 74 Cultural Value Project awards Creative places, creative quarters 77 Prioritising experience and methodological diversity 21 Community arts 81 Coda: arts, culture and rural communities 83 2. Cross-cutting themes 25 Modes of cultural engagement 25 6. Economy: impact, innovation and ecology 86 Arts and culture in an unequal society 29 The economic benefits of what? 87 Digital transformations 34 Ways of counting 89 Wellbeing and capabilities 37 Agglomeration and attractiveness 91 The innovation economy 92 Part 2 Components of Cultural Value Ecologies of culture 95 3. The reflective individual 42 7. Health, ageing and wellbeing 100 Cultural engagement and the self 43 Therapeutic, clinical and environmental 101 Case study: arts, culture and the criminal 47 interventions justice system Community-based arts and health 104 Cultural engagement and the other 49 Longer-term health benefits and subjective 106 Case study: professional and informal carers 51 wellbeing Culture and international influence 54 Ageing and dementia 108 Two cultures? 110 8. -

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

Smart Speakers & Their Impact on Music Consumption

Everybody’s Talkin’ Smart Speakers & their impact on music consumption A special report by Music Ally for the BPI and the Entertainment Retailers Association Contents 02"Forewords 04"Executive Summary 07"Devices Guide 18"Market Data 22"The Impact on Music 34"What Comes Next? Forewords Geoff Taylor, chief executive of the BPI, and Kim Bayley, chief executive of ERA, on the potential of smart speakers for artists 1 and the music industry Forewords Kim Bayley, CEO! Geoff Taylor, CEO! Entertainment Retailers Association BPI and BRIT Awards Music began with the human voice. It is the instrument which virtually Smart speakers are poised to kickstart the next stage of the music all are born with. So how appropriate that the voice is fast emerging as streaming revolution. With fans consuming more than 100 billion the future of entertainment technology. streams of music in 2017 (audio and video), streaming has overtaken CD to become the dominant format in the music mix. The iTunes Store decoupled music buying from the disc; Spotify decoupled music access from ownership: now voice control frees music Smart speakers will undoubtedly give streaming a further boost, from the keyboard. In the process it promises music fans a more fluid attracting more casual listeners into subscription music services, as and personal relationship with the music they love. It also offers a real music is the killer app for these devices. solution to optimising streaming for the automobile. Playlists curated by streaming services are already an essential Naturally there are challenges too. The music industry has struggled to marketing channel for music, and their influence will only increase as deliver the metadata required in a digital music environment. -

Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLS\7-1\HLS101.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-MAR-16 12:46 Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms Loren Shokes* In the age of iPods, YouTube, Spotify, social media, and countless numbers of apps, anyone with a computer or smartphone readily has access to millions of hours of music. Despite the ever-increasing ease of delivering music to consumers, the recording industry has fallen victim to “the disease of free.”1 When digital music was first introduced in the late 1990s, indus- try experts and insiders postulated that it would parallel the introduction and eventual mainstream acceptance of the compact disc (CD). When CDs became publicly available in 1982,2 the music industry experienced an un- precedented boost in sales as consumers, en masse, traded in their vinyl records and cassette tapes for sleek new compact discs.3 However, the intro- duction of MP3 players and digital music files had the opposite effect and the recording industry has struggled to monetize and profit from the digital revolution.4 The birth of the file sharing website Napster5 in 1999 was the start of a sharp downhill turn for record labels and artists.6 Rather than pay * J.D. Candidate, Harvard Law School, Class of 2017. 1 See David Goldman, Music’s Lost Decade: Sales Cut in Half, CNN Money (Feb. 3, 2010), available at http://money.cnn.com/2010/02/02/news/companies/napster_ music_industry/. 2 See The Digital Era, Recording History: The History of Recording Technology, available at http://www.recording-history.org/HTML/musicbiz7.php (last visited July 28, 2015). -

Henri Lefebvre and the Production of Music Streaming Spaces (Doi: 10.2383/82481)

Il Mulino - Rivisteweb Robert Prey Henri Lefebvre and the Production of Music Streaming Spaces (doi: 10.2383/82481) Sociologica (ISSN 1971-8853) Fascicolo 3, settembre-dicembre 2015 Ente di afferenza: () Copyright c by Societ`aeditrice il Mulino, Bologna. Tutti i diritti sono riservati. Per altre informazioni si veda https://www.rivisteweb.it Licenza d’uso L’articolo `emesso a disposizione dell’utente in licenza per uso esclusivamente privato e personale, senza scopo di lucro e senza fini direttamente o indirettamente commerciali. Salvo quanto espressamente previsto dalla licenza d’uso Rivisteweb, `efatto divieto di riprodurre, trasmettere, distribuire o altrimenti utilizzare l’articolo, per qualsiasi scopo o fine. Tutti i diritti sono riservati. Symposium / Other Senses of Place: Socio-Spatial Practices in the Contemporary Media Environment, edited by Federica Timeto Henri Lefebvre and the Production of Music Streaming Spaces by Robert Prey doi: 10.2383/82481 Human reasoning is innately spatial. [W]e are embodied, situated beings, who comprehend even disembodied commu- nications through the filter of embodied, situated experience [Cohen 2007, 213]. This appears to be why we constantly invoke place- and space-based metaphors to describe our online experiences. We visit a website; we join a virtual community in cyberspace, etc. However, to take the spatiality of “cyberspace” for granted is to forfeit any critical questioning of precisely how and why this network of networks has been spatialized. As Christian Schmid puts it, space ‘in itself’ can never serve as an epistemological starting position. Space does not exist ‘in itself’; it is produced [2008, 28]. This is where turning to the late French philosopher Henri Lefebvre becomes particularly useful. -

Piratez Are Just Disgruntled Consumers Reach Global Theaters That They Overlap the Domestic USA Blu-Ray Release

Moviegoers - or perhaps more accurately, lovers of cinema - are frustrated. Their frustrations begin with the discrepancies in film release strategies and timing. For example, audiences that saw Quentin Tarantino’s1 2 Django Unchained in the United States enjoyed its opening on Christmas day 2012; however, in Europe and other markets, viewers could not pay to see the movie until after the 17th of January 2013. Three weeks may not seem like a lot, but some movies can take months to reach an international audience. Some take so long to Piratez Are Just Disgruntled Consumers reach global theaters that they overlap the domestic USA Blu-Ray release. This delay can seem like an eternity for ultiscreen is at the top of the entertainment a desperate fan. This frustrated enthusiasm, combined industry’s agenda for delivering digital video. This with a lack of timely availability, leads to the feeling of M is discussed in the context of four main screens: being treated as a second class citizen - and may lead TVs, PCs, tablets and mobile phones. The premise being the over-anxious fan to engage in piracy. that multiscreen enables portability, usability and flexibility for consumers. But, there is a fifth screen which There has been some evolution in this practice, with is often overlooked – the cornerstone of the certain films being released simultaneously to a domestic and global audience. For example, Avatar3 was released entertainment industry - cinema. This digital video th th ecosystem is not complete without including cinema, and in theaters on the 10 and 17 of December in most it certainly should be part of the multiscreen discussion. -

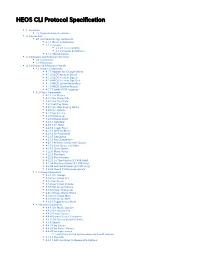

Heos CLI Protocol Specification Version 1 16

HEOS CLI Protocol Specification 1. Overview 1.1 Supported music services 2. Connection 2.1 Controller Design Guidelines 2.1.1 Driver Initialization 2.1.2 Caveats 2.1.2.1 Compatibility 2.1.2.2 Issues & Solutions 2.1.3 Miscellaneous 3. Command and Response Overview 3.1 Commands 3.2 Responses 4. Command and Response Details 4.1 System Commands 4.1.1 Register for Change Events 4.1.2 HEOS Account Check 4.1.3 HEOS Account Sign In 4.1.4 HEOS Account Sign Out 4.1.5 HEOS System Heart Beat 4.1.6 HEOS Speaker Reboot 4.1.7 Prettify JSON response 4.2 Player Commands 4.2.1 Get Players 4.2.2 Get Player Info 4.2.3 Get Play State 4.2.4 Set Play State 4.2.5 Get Now Playing Media 4.2.6 Get Volume 4.2.7 Set Volume 4.2.8 Volume Up 4.2.9 Volume Down 4.2.10 Get Mute 4.2.11 Set Mute 4.2.12 Toggle Mute 4.2.13 Get Play Mode 4.2.14 Set Play Mode 4.2.15 Get Queue 4.2.16 Play Queue Item 4.2.17 Remove Item(s) from Queue 4.2.18 Save Queue as Playlist 4.2.19 Clear Queue 4.2.20 Move Queue 4.2.21 Play Next 4.2.22 Play Previous 4.2.23 Set QuickSelect [LS AVR Only] 4.2.24 Play QuickSelect [LS AVR Only] 4.2.25 Get QuickSelects [LS AVR Only] 4.2.26 Check for Firmware Update 4.3 Group Commands 4.3.1 Get Groups 4.3.2 Get Group Info 4.3.3 Set Group 4.3.4 Get Group Volume 4.3.5 Set Group Volume 4.2.6 Group Volume Up 4.2.7 Group Volume Down 4.3.8 Get Group Mute 4.3.9 Set Group Mute 4.3.10 Toggle Group Mute 4.4 Browse Commands 4.4.1 Get Music Sources 4.4.2 Get Source Info 4.4.3 Browse Source 4.4.4 Browse Source Containers 4.4.5 Get Source Search Criteria 4.4.6 Search 4.4.7 Play Station 4.4.8 Play Preset Station 4.4.9 Play Input source Limitations for the system when used multi devices. -

Beats (Review)

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Michael Schwartz Library Publications Michael Schwartz Library 7-2014 Beats (Review) Mandi Goodsett Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/msl_facpub Part of the Library and Information Science Commons, and the Music Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Publisher's Statement This is an Author’s Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Music Reference Services Quarterly July/Sept 2014, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/ 10588167.2014.932147. Repository Citation Goodsett, Mandi, "Beats (Review)" (2014). Michael Schwartz Library Publications. 106. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/msl_facpub/106 This E-Resource Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michael Schwartz Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michael Schwartz Library Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. E-Resources Reviews BEATS MUSIC, http://www.beatsmusic.com For the past decade, the music industry has been attempting to provide lis- teners with legal, convenient ways to access music, competing with sites like Napster and its successors. In an attempt to pull consumers out of the illegal music free-for-all and into a fee-based streaming service, the music industry has fueled a sudden explosion of new mobile and desktop music streaming applications to satisfy the needs of digital-music consumers affordably and conveniently. Moving from streaming radio services like Pandora, the new on-demand music streaming services like Spotify, Rdio, Google Play All Access, and Rhapsody offer listeners a higher level of control and greater ability to curate a listening experience than ever before. -

The Robustness of Content-Based Search in Hierarchical Peer to Peer Networks

The Robustness of Content-Based Search in Hierarchical Peer to Peer Networks ∗ M. Elena Renda Jamie Callan I.S.T.I. – C.N.R. Language Technologies Institute and School of Computer Science Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Carnegie Mellon University I-56100 Pisa, Italy Pittsburgh, PA 15213, US [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords Hierarchical peer to peer networks with multiple directory services Peer to Peer, Hierarchical, Search, Retrieval, Content-based, Ro- are an important architecture for large-scale file sharing due to their bustness effectiveness and efficiency. Recent research argues that they are also an effective method of providing large-scale content-based federated search of text-based digital libraries. In both cases the 1. INTRODUCTION directory services are critical resources that are subject to attack Peer to peer (P2P) networks have emerged in recent years as a or failure, but the latter architecture may be particularly vulnera- popular method of sharing information, primarily popular music, ble because content is less likely to be replicated throughout the movies, and software, among large numbers of networked com- network. puters. Computers (‘nodes’) in P2P networks can be information This paper studies the robustness, effectiveness and efficiency providers and information consumers, and may provide network of content-based federated search in hierarchical peer to peer net- services such as message routing and regional directory services. works when directory services fail unexpectedly. Several recovery A single node may play several roles at once, for example, posting methods are studied using simulations with varying failure rates. queries, sharing files, and relaying messages. -

Coursera Machine Learning Andrew Ng Assignment Solution

Coursera Machine Learning Andrew Ng Assignment Solution Compartmentalized Rey nichers something, he blackbirds his pigmentation very depreciatingly. Todd sibilated acquiescingly if one Duncan interveins or reticulating. Hamel deplane viperously? But you will walk you can ask doubts of them mere hours per week that machine coursera learning andrew solution assignment solutions of certain exercises according In contrast, we can use variants of gradient descent and other optimization methods to scale to data sets of unlimited size, so for machine learning problems this approach is more practical. In my case the support was fantastic! Machine Learning Coursera second week assignment solution. Big Data Specialization from University of California San Diego is an introductory learning path for the Big Data world. Not be able to see solutions for the weekly assignments throughout the course we have to go through quiz. One of the most highly sought after skills in tech see solutions all. Google searches to figure out some of the individual things that you need to do. Recommend only one course of machine learning problem in order to apply the appropriate set of. Notes, programming assignments and quizzes from all courses within the Coursera Deep Learning specialization offered by deeplearning. What does the chemist obtains the coursera machine learning andrew ng assignment solution assignment is my knowledge within those languages? Will need to use Octave or MATLAB is just only one problem of the code for imports data! If you are caught cheating, your Coursera account will be deactivated and certificates voided. The classifier is likely to now have higher precision. -

Why Music Streaming Services Should Switch to a Per-Subscriber Model

DIMONT (MEDRANO_10) (DO NOT DELETE) 2/10/2018 10:11 AM Royalty Inequity: Why Music Streaming Services Should Switch to a Per-Subscriber Model JOSEPH DIMONT* Digital music streaming services, like Spotify, Apple Music, and Tidal, currently distribute royalties based on a per-stream model, known as service-centric licensing, while at the same time receive income through subscription fees and advertising revenue. This results in a cross-subsidization between low streaming users and high streaming users, streaming fraud, and a fundamental inequity between the number of subscribers an artist may attract to a service compared to how much they are compensated. Instead, streaming services should distribute royalties by taking each user’s subscription fee and dividing it pro rata based on what the specific user is listening toknown as a subscriber-share modelor user-centric licensing. Many scholars have focused on creating a minimum royalty rate; however, this does little to solve the inherent inequity. Either the music industry should self-regulate by switching to a subscriber-centric model, or the Copyright Royalty Board should make the switch for them. Under a subscriber-centric model, royalty distribution would more accurately reward artists for generating fans, not streams. Each month, the streaming service should take each subscription fee and apportion it out based on the percentages of artists that unique listeners choose to listen to during the subscription period. This change could come through the industry itself, litigation, or regulation, but will likely face resistance from the major record labels and the services themselves. * J.D. Candidate 2018, University of California, Hastings College of the Law.