Written Evidence Submitted by Hipgnosis Songs Fund Limited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hipgnosis Songs Fund Limited

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take or the contents of this Prospectus, you are recommended to seek your own independent financial advice immediately from your stockbroker, bank, solicitor, accountant, or other appropriate independent financial adviser, who is authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (the “FSMA”) if you are in the United Kingdom, or from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser if you are in a territory outside the United Kingdom. A copy of this document, which comprises a prospectus relating to Hipgnosis Songs Fund Limited (the “Company”) in connection with the issue of Issue Shares in the Company and their admission to trading on the Main Market and to listing on the premium listing category of the Official List, prepared in accordance with the Prospectus Rules of the FCA made pursuant to section 73A of the FSMA, has been filed with the Financial Conduct Authority in accordance with Rule 3.2 of the Prospectus Rules. The Prospectus has been approved by the FCA, as competent authority under the Prospectus Regulation and the FCA only approves this Prospectus as meeting the standards of completeness, comprehensibility and consistency imposed by the Prospectus Regulation. Accordingly, such approval should not be considered as an endorsement of the issuer, or of the quality of the securities, that are the subject of this Prospectus; investors should make their own assessment as to the suitability of investing in the Issue Shares. The Issue Shares are only suitable for investors: (i) who understand the potential risk of capital loss and that there may be limited liquidity in the underlying investments of the Company; (ii) for whom an investment in the Issue Shares is part of a diversified investment programme; and (iii) who fully understand and are willing to assume the risks involved in such an investment programme. -

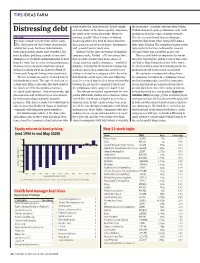

Distressing Debt Seek out Shares in the Lowest Quality Companies; Verdad Compared Equity Performance with Credit the Worst-Of-The-Worst, If You Like

TIPS IDEAS FARM want to play the ‘dash for trash’ should simply the issue price. A similar story was found when Distressing debt seek out shares in the lowest quality companies; Verdad compared equity performance with credit the worst-of-the-worst, if you like. However, quality based on the scores of rating agencies. ALGY HALL ignoring ‘quality’ when it comes to buying Here the research found share performance t’s been a tough time for short sellers lately. beaten-up stocks (the kind of shares found on started to deteriorate when ratings fell below a IThe ‘dash for trash’ that I wrote about in this these pages in our tables of shorts, downgrades high single B rating. The annualised equity return column last week, has been indiscriminate. and 52-week lows) is rarely wise. from stocks in the least creditworthy category Even real no-hoper shares have benefited. The Intrigued by the price movement of bankrupt- (CC and below) was a negative 34 per cent. most headline-grabbing example of investors’ company stocks, Verdad – a US investment firm This research holds an important lesson for willingness to overlook all fundamentals in their that specialises in investing in the shares of investors targeting the grubbier end of this recov- hunt for ‘trash’ has been the strong performance cheap, indebted, smaller companies – trawled its ery. Rather than buying the worst-of-the-worst, of shares in US companies that have already database. It looked for the long-term relationship it’s the best-of-the-worst that should provide the declared bankruptcy or are about to (Hertz, JC between share price performance and the level optimal trade-off between risk and reward. -

February 12, 2019: SXSW Announces Additional Keynotes and Featured

SOUTH BY SOUTHWEST ANNOUNCES ADDITIONAL KEYNOTES AND FEATURED SPEAKERS FOR 2019 CONFERENCE Adam Horovitz and Michael Diamond of Beastie Boys, John Boehner, Kara Swisher, Roger McNamee, and T Bone Burnett Added to the Keynote Lineup Stacey Abrams, David Byrne, Elizabeth Banks, Aidy Bryant, Brandi Carlile, Ethan Hawke, Padma Lakshmi, Kevin Reilly, Nile Rodgers, Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, and More Added as Featured Speakers Austin, Texas — February 12, 2019 — South by Southwest® (SXSW®) Conference and Festivals (March 8–17, 2019) has announced further additions to their Keynote and Featured Speaker lineup for the 2019 event. Keynotes announced today include former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives John Boehner with Acreage Holdings Chairman and CEO Kevin Murphy; a Keynote Conversation with Adam Horovitz and Michael Diamond of Beastie Boys with Amazon Music’s Nathan Brackett; award-winning producer, musician and songwriter T Bone Burnett; investor and author Roger McNamee with WIRED Editor in Chief Nicholas Thompson; and Recode co-founder and editor-at-large Kara Swisher with a special guest. Among the Featured Speakers revealed today are national political trailblazer Stacey Abrams, multi-faceted artist David Byrne; actress, producer and director Elizabeth Banks; actress, writer and producer Aidy Bryant; Grammy Award-winning musician Brandi Carlile joining a conversation with award-winning actress Elisabeth Moss; professional wrestler Charlotte Flair; -

Invesco UK 2 Investment Series Annual Report 2019

01 Front Cover_Layout 1 02-Jul-19 11:48 AM Page 1 Invesco UK 2 Investment Series Annual Report Including Long Form Financial Statements Issued July 2019 For the year 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019 02 Aggregate_Layout 1 02-Jul-19 11:48 AM Page 1 Contents Invesco UK 2 Investment Series (the “Company”) 02 Report of the Authorised Corporate Director (the “Manager”)* 06 Notes applicable to the financial statements of all Sub-Funds 13 Invesco Income Fund (UK) 14 Strategy, review and outlook* 15 Comparative tables 19 Portfolio statement* 23 Financial statements 32 Distribution tables 34 Invesco UK Enhanced Index Fund (UK) 35 Strategy, review and outlook* 36 Comparative tables 39 Portfolio statement* 43 Financial statements 51 Distribution tables 52 Invesco UK Strategic Income Fund (UK) 53 Strategy, review and outlook* 54 Comparative tables 58 Portfolio statement* 61 Financial statements 70 Distribution tables 72 Regulatory Statements 72 Statement of Manager's responsibilities 72 Statement of Depositary’s responsibilities 72 Depositary’s Report to Shareholders 73 Independent Auditors’ Report 75 General Information * These collectively comprise the Authorised Corporate Director’s Report. 01 Invesco UK 2 Investment Series 02 Aggregate_Layout 1 02-Jul-19 11:48 AM Page 2 Invesco UK 2 Investment Series (the “Company”) Report of the Authorised Corporate Director (the “Manager”) The Company Remuneration Policy (Unaudited) The Invesco UK 2 Investment Series is an investment On 18 March 2016, Invesco Fund Managers company with variable capital, incorporated in England Limited (the “Manager”) adopted a remuneration and Wales on 11 April 2003. policy consistent with the principles outlined in the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) The Company is a “UCITS Scheme” and an “Umbrella Guidelines, on sound remuneration policies under Company” (under the OEIC Regulations) and therefore the UCITS Directive (the "Remuneration Policy"). -

Interim Report and Financial Statements

Fidelity Investment Funds Interim Report and Financial Statements For the six months ended 31 August 2020 Fidelity Investment Funds Interim Report and Financial Statements for the six month period ended 31 August 2020 Contents Director’s Report* 1 Statement of Authorised Corporate Director’s Responsibilities 2 Director’s Statement 3 Authorised Corporate Director’s Report*, including the financial highlights and financial statements Market Performance Review 4 Summary of NAV and Shares 6 Accounting Policies of Fidelity Investment Funds and its Sub-funds 9 Fidelity American Fund 10 Fidelity American Special Situations Fund 12 Fidelity Asia Fund 14 Fidelity Asia Pacific Opportunities Fund 16 Fidelity Asian Dividend Fund 18 Fidelity Cash Fund 20 Fidelity China Consumer Fund 22 Fidelity Emerging Asia Fund 24 Fidelity Emerging Europe, Middle East and Africa Fund 26 Fidelity Enhanced Income Fund 28 Fidelity European Fund 30 Fidelity European Opportunities Fund 32 Fidelity Extra Income Fund 34 Fidelity Global Dividend Fund 36 Fidelity Global Enhanced Income Fund 38 Fidelity Global Focus Fund 40 Fidelity Global High Yield Fund 42 Fidelity Global Property Fund 44 Fidelity Global Special Situations Fund 46 Fidelity Index Emerging Markets Fund 48 Fidelity Index Europe ex UK Fund 50 Fidelity Index Japan Fund 52 Fidelity Index Pacific ex Japan Fund 54 Fidelity Index Sterling Coporate Bond Fund 56 Fidelity Index UK Fund 58 Fidelity Index UK Gilt Fund 60 Fidelity Index US Fund 62 Fidelity Index World Fund 64 Fidelity Japan Fund 66 Fidelity Japan Smaller -

Important Notice

IMPORTANT NOTICE NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION TO ANY U.S. PERSON OR TO ANY PERSON OR ADDRESS IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (“UNITED STATES”) IMPORTANT: You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the Registration Document (the "Registration Document" or the “Document”) following this page, and you are therefore advised to read this carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the Registration Document. In accessing the Registration Document, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them any time you receive any information from us as a result of such access. NOTHING IN THIS REGISTRATION DOCUMENT CONSTITUTES AN OFFER TO SELL OR THE SOLICITATION OF AN OFFER TO BUY THE SECURITIES OF THE ISSUER IN THE UNITED STATES OR ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. THE BONDS HAVE NOT BEEN AND WILL NOT BE REGISTERED UNDER THE UNITED STATES SECURITIES ACT OF 1933, AS AMENDED (THE "SECURITIES ACT"), OR ANY SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OF THE UNITED STATES. THE BONDS MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD WITHIN THE UNITED STATES OR TO, OR FOR THE ACCOUNT OR BENEFIT OF, U.S. PERSONS ("U.S. PERSONS"), AS DEFINED IN REGULATION S UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT ("REGULATIONS"), NOR U.S. RESIDENTS (AS DETERMINED FOR THE PURPOSES OF THE U.S. INVESTMENT COMPANY ACT OF 1940) ("U.S. RESIDENTS") EXCEPT PURSUANT TO AN EXEMPTION FROM SUCH REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS. WITHIN THE UNITED KINGDOM (“UK”), THIS REGISTRATION DOCUMENT IS DIRECTED ONLY AT PERSONS WHO HAVE PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE IN MATTERS RELATING TO INVESTMENTS AND WHO QUALIFY EITHER AS INVESTMENT PROFESSIONALS IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 19(5) OR AS HIGH NET WORTH COMPANIES, UNINCORPORATED ASSOCIATIONS, PARTNERSHIPS OR TRUSTEES IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 49(2) OF THE FINANCIAL SERVICES AND MARKETS ACT 2000 (FINANCIAL PROMOTION) ORDER 2005 (TOGETHER, "EXEMPT PERSONS"). -

Songwriting Studies at the Ivors Academy Press Release

EMBARGOED UNTIL 12 NOON THURS 8th AUGUST 2019 Nile Rodgers delivers keynote speech as songwriters Get Lucky. Ivor Novello Award-winning musician and producer Nile Rodgers surprised a room full of songwriters, music industry workers, and academics on 8th August, emerging as the unannounced keynote speaker for the Songwriting Studies Research Network event held at The Ivors Academy in London, UK. Billed as a conference around the activities of an academic research network, delegates had expected a day full of panel discussions, debates, and papers, but alongside the advertised schedule they also witnessed an intimate, hour-long discussion between Rodgers and music manager Merck Mercuriadis. In a rapid-fire exchange the pair covered a variety of topics, including the future of music publishing and the secrets of songwriting success, before answering questions from the crowd. Research project leader, Dr Simon Barber from the Birmingham Centre for Media and Cultural Research at Birmingham City University, said: “Getting these kinds of rarefied insights from people who have ascended the upper echelons of the music industries is priceless. We can’t thank Nile and Merck enough for spending time answering our questions and sharing their expertise with the network.” The event – the second in a series of national forums organised by the network – also saw the launch of the Songwriting Studies Journal, a new publication edited by Barber that will develop and share work from researchers and practitioners related to the culture and practice of songwriting. Delegates went away with details of the first issue and an invitation to contribute. Following the event at The Ivors Academy, Rodgers and Mercuriadis then joined Dr Barber and his colleague Brian O’Connor for a live recording of their renowned podcast Sodajerker On Songwriting at the Queen Elizabeth Hall as part of the Meltdown Festival, capping off a day when the role of the songwriter was the focus for all. -

July 2019 Main Auditorium, Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, Glasgow 28Th July 2019 Royal Fes�Val Hall, Southbank Centre, London

(Header by Sven Kramer) Welcome to this month's new readers, from several different countries. Please join in! We would love to hear from you. Not long to go now before Russ appears with Trevor Horn. There are links for Hckets below. Just in case you haven't got round to finding the Estoril videos on TouTube, I have found one for you. A big favourite and thanks to Ian for the video. ANer a couple of months' break while we had all the "Experience" and Estoril pieces, Dave is back working his magic on the cover stories. Scroll down to the end and you will find Russ's friend from Portugal, Vania and her band, with a very beauHful song wriSen by Russ and Chris Winter. Dave's 'history' arHcle is about the song, I Surrender. So many covers of it! We have included six video previews with some very different versions but look for several other links in amongst them. For the most different version, have a listen to Sue Ellen. And, guess who Russ has been meeHng up with....read on! Sue THIS MONTH FROM RUSS "Chris'an sent ‘It’s Good To Be Here’ to be mastered, which I’m glad to say, it now is. However, three weeks ago, while listening to song ideas from last year that I recorded on my phone, there was one chorus I par'cularly liked, (just piano & voice). Believe it or not, I decided to finish the song and record it. Ian Ramage from BMG (my label) phoned to say he wanted to send the album to other countries, for them to plan the release. -

FTSE UK Index Series – Indicative Quarterly Review Changes September 2020

Press Release 26 August 2020 FTSE UK Index Series – Indicative Quarterly Review Changes September 2020 FTSE Russell, the global index provider, advises of the following indicative changes to the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250, based on data as at Friday 21 August. PLEASE NOTE: The actual review of the FTSE UK Index Series will be conducted using data as at market close on Tuesday 1 September 2020. Confirmed rebalance changes will be announced after market close on Wednesday 2 September 2020. Indicative FTSE 100 Additions (in alphabetical order) Indicative FTSE 100 Deletions (in alphabetical order) • B&M European Value Retail • ITV Indicative FTSE 250 Additions (in alphabetical order) Indicative FTSE 250 Deletions (in alphabetical order) • CMC Markets • B&M European Value Retail • Diversified Gas & Oil • Bank of Georgia Group • Hipgnosis Songs Fund C * • Equiniti Group • Indivior • Go-Ahead Group • ITV • Hammerson • JPMorgan Euro Small Co. Trust • PayPoint • Premier Foods • PPHE Hotel Group • Vectura Group *Hipgnosis Songs Fund C is a secondary line of Hipgnosis ENDS For further information: Global Media Lucie Holloway/ Oliver Mann +44 (0)20 7797 1222 [email protected] 1 Press Release Notes to editors: FTSE Russell is revising the timing of its publication of indicative changes to the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250, starting from this September’s quarterly review and on an on-going basis. Instead of publishing indicative changes via a press release two trading days prior to the final results announcement, FTSE Russell will now publish its indicative changes via a press release after market close in the week prior. For the September review, this means that we will publish indicative positions on Wednesday, 26th August, based on closing prices from Friday 21st August. -

Hipgnosis Songs

Disclosure – Non-Independent Marketing Communication This is a non-independent marketing communication commissioned by Hipgnosis Songs. The report has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is not subject to any prohibition on the dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research. Update Hipgnosis Songs 19 September 2019 Summary Hipgnosis Songs Fund (SONG) is a £409m market cap listed fund, aiming to achieve income and capital growth by owning songwriters’ music royalties. The managers (The Analysts: Family (Music) Ltd) believe that, aside from being able to buy these royalties from William Heathcoat Amory songwriters on a gross yield of c. 8%, investors should benefit rf om trends and active +44 (0)203 384 8795 management, which will increase the level of income (and capital value) over time. Pascal Dowling The managers are aiming for total returns of greater than 10%, and have +44 (0)203 384 8869 demonstrated their ability to invest the fund’s capital relatively quickly – no mean feat in a market where there are no formal brokers or “exchange” for royalties. Merck Thomas McMahon, CFA Mercuriadis leads the management team, and he is clearly a music industry +44 (0)203 795 0070 “insider”; we understand his relationships have been key to accessing the quality of the portfolio that SONG has built up so far. William Sobczak +44 (0)203 598 6449 Having spoken to the team, they tell us that royalties from the copyright of songs tend to be relatively predictable – certainly after the first hreet years when the “buzz” has Callum Stokeld largely subsided. -

Issue 419 | 19 December 2018 End-Of-Year Report 1

thereport ISSUE 419 | 19 DECEMBER 2018 END-OF-YEAR REPORT 1 ISSUE 419 19.12.18 Hope and No.1 glory treaming subscriptions have trend, with three, growth excitement about the potential in brought growth back to the streaming is fuelling the China, India and Africa, there is much music industry – and in 2018 subscriptions the confidence to invest to celebrate from 2018. that has fuelled optimism and driving force. – in artists, technology and That’s not to say the year didn’t Sinvestment. The US, for example, saw copyrights alike. throw up some worries, arguments The global recorded-music industry 10% growth in the first half of 2018 for This is the key music industry trend and even the odd existential debate: lost 56% of its value between 1999 and both retail spending and wholesale of 2018. This is a growth industry once from Spotify’s growing pains, sluggish 2014, falling from annual revenues of revenues from recorded music, with more, and that is driving the decisions markets in Germany and Japan, and the $25.2bn to $14.2bn, according to the 46.4m music subscribers spending of the people within it, as well as failure to deliver (so far) of technologies IFPI. The memory of that 15-year period $2.55bn on their subscriptions – up 33% those outside with the resources to like VR and blockchain to the ever-tense should be enough to stop anyone in year-on-year and now accounting for invest in it. Optimism is back, although ‘value gap’ battles. our industry getting too carried away 55.4% of total spending. -

Investec Funds Series I Annual Report and Accounts for the Year Ended 30 September 2018 REPORT and ACCOUNTS Investec Funds Series I Annual Report and Accounts

OEIC | REPORT AND ACCOUNTS INVESTEC FUNDS SERIES I Investec Funds Series i Annual Report and Accounts For the year ended 30 September 2018 REPORT AND ACCOUNTS Investec Funds Series i Annual Report and Accounts Cautious Managed Fund* 2-4 Diversifi ed Income Fund* 5-7 Enhanced Natural Resources Fund* 8-10 Global Multi-Asset Total Return Fund* 11-13 UK Alpha Fund* 14-16 UK Equity Income Fund* 17-19 UK Smaller Companies Fund* 20-23 UK Special Situations Fund* 24-26 Portfolio Statements per Fund* 27-59 Authorised Corporate Director’s Report* 60-61 Statement of Depositary’s Responsibilities and Report to Shareholders 62 Independent Auditor’s Report 63-64 Statement of Authorised Corporate Director’s Responsibilities65 Comparative Tables 66-90 Financial Statements 91-178 Securities Financing Transactions (‘SFTs’) 179 Other Information180 Glossary 181-183 Directory 184 * The above information collectively forms the Authorised Corporate Director’s Report Investec Funds Series i 1 REPORT AND ACCOUNTS Cautious Managed Fund Summary of the Fund’s investment objective and policy The Fund aims to provide income and long-term capital growth. The Fund seeks to invest conservatively around the world in a diverse range of shares of companies (up to 60% of the Fund’s value at any time) and bonds (contracts to repay borrowed money which typically pay interest at fi xed times). The Fund may invest in other assets such as cash, other funds and derivatives (fi nancial contracts whose value is linked to the price of an underlying asset). The Investment Manager is free to choose how the Fund is invested and does not manage it with reference to an index.