A Methodological Study of the Effect of Experimentally Induced Demand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Cognitive Factors in the Development of Seasonal Affective Disorder Episodes Stacy Whitcomb-Smith

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 12-2003 The Role of Cognitive Factors in the Development of Seasonal Affective Disorder Episodes Stacy Whitcomb-Smith Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Whitcomb-Smith, Stacy, "The Role of Cognitive Factors in the Development of Seasonal Affective Disorder Episodes" (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 55. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/55 This Open-Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. THE ROLE OF COGNITIVE FACTORS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF SEASONAL AFFECTIVE DISORDER EPISODES BY Stacy Whitcomb-Smith B.A., Williams College, 1995 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in Psychology) The Graduate School The University of Maine December, 2003 Advisory Committee: Sandra T. Sigrnon, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Psychology, Chairperson Jeffrey Hecker, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Psychology Michael Robbins, Ph.D., Associate Research Professor of Psychology Alan Rosenwasser, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology Geoffrey Thorpe, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology O 2003 Stacy Whitcomb-Smith All Rights Reserved LIBRARY RIGHTS STATEMENT In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Maine, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for "fair use" copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Librarian. -

Wishful Thinking About the Future: Does Desire Impact Optimism? Zlatan Krizan1* and Paul D

Social and Personality Psychology Compass 3/3 (2009): 227–243, 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00169.x WishfulBlackwellOxford,SPCOSocial1751-9004©Journal16910.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00169.xMarch0227???243???Original 2009 and2009 Thinking UKTheCompilationArticle Publishing Personality Authors ©Ltd Psychology2009 Blackwell Compass Publishing Ltd. Wishful Thinking about the Future: Does Desire Impact Optimism? Zlatan Krizan1* and Paul D. Windschitl2 1 Iowa State University 2 University of Iowa Abstract The notion that desire for an outcome inflates optimism about that outcome has been dubbed the desirability bias or wishful thinking. In this paper, we discuss the importance of distinguishing wishful thinking from the more general concept of motivated reasoning, and we explain why documenting overoptimism or correla- tions between preferences and optimism is not sufficient to infer a desirability bias. Then, we discuss results from a review and meta-analysis of the experimental litera- ture on wishful thinking. These findings, in conjunction with more recent work, not only highlight important moderators and mediators of the desirability bias but also point out limitations of the empirical research on the bias. These results also reveal an important difference between how likelihood judgments and discrete outcome predictions respond to desirability of outcomes. We conclude by presenting avenues for future research useful for understanding wishful thinking’s manifesta- tion in everyday environments and its integration with related phenomena. —A soon-to-be bride and groom who hope the weather will cooperate on their wedding day. —An Illinois grade-schooler who thinks it would be ‘pretty cool’ if Chicago was indeed selected as the host city for the 2016 Olympics. -

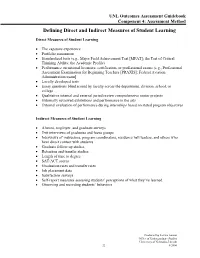

Assessment Method Defining Direct and Indirect Measures of Student Learning

UNL Outcomes Assessment Guidebook Component 4: Assessment Method Defining Direct and Indirect Measures of Student Learning Direct Measures of Student Learning • The capstone experience • Portfolio assessment • Standardized tests (e.g., Major Field Achievement Test [MFAT]; the Test of Critical Thinking Ability; the Academic Profile) • Performance on national licensure, certification, or professional exams (e.g., Professional Assessment Examination for Beginning Teachers [PRAXIS]; Federal Aviation Administration exam] • Locally developed tests • Essay questions blind scored by faculty across the department, division, school, or college • Qualitative internal and external juried review comprehensive senior projects • Externally reviewed exhibitions and performance in the arts • External evaluation of performance during internships based on stated program objectives Indirect Measures of Student Learning • Alumni, employer, and graduate surveys • Exit interviews of graduates and focus groups • Interviews of instructors, program coordinators, residence hall leaders, and others who have direct contact with students • Graduate follow-up studies • Retention and transfer studies • Length of time to degree • SAT/ACT scores • Graduation rates and transfer rates • Job placement data • Satisfaction surveys • Self-report measures assessing students’ perceptions of what they’ve learned • Observing and recording students’ behaviors Produced by Jessica Jonson Office of Undergraduate Studies University of Nebraska-Lincoln 22 8/2006 UNL Outcomes Assessment Guidebook Component 4: Assessment Method Advantages and Disadvantages of Potential Assessment Methods SOURCE: American Psychological Association Online (http://www.apa.org/ed/eval_strategies.html) In this section we examine and evaluate the value of each of the major assessment categories. We conclude the discussion of each strategy with specific recommendations to maximize the utility of the following approaches: a. -

Ecological Validity Research-Article9667912021

PPSXXX10.1177/1745691620966791KihlstromEcological Validity 966791research-article2021 ASSOCIATION FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Perspectives on Psychological Science 2021, Vol. 16(2) 466 –471 Ecological Validity and “Ecological © The Author(s) 2021 Article reuse guidelines: Validity” sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620966791 10.1177/1745691620966791 www.psychologicalscience.org/PPS John F. Kihlstrom Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley Abstract Egon Brunswik coined the term ecological validity to refer to the correlation between perceptual cues and the states and traits of a stimulus. Martin Orne adapted the term to refer to the generalization of experimental findings to the real world outside the laboratory. Both are legitimate uses of the term because the ecological validity of the cues in an experiment determines the ecological validity of the experiment itself. Keywords demand characteristics, ecological validity, behavioral methodology, neuroscience methodology, scientific methodology Recently in this journal, Shamay-Tsoory and Men- of complex natural situations in the laboratory to deter- delsohn (2019) called attention to the “limited ecological mine cause-and-effect relations. But he also argued that validity that characterizes the bulk of the paradigms and artificial laboratory situations have features of their own settings” (p. 841) in cognitive neuroscience. Holleman that may differ from those found in the natural environ- et al. (2021), while supporting their call for more lifelike ment and that threaten generalization from the labora- stimuli and tasks in brain-imaging studies, criticized tory back to the real world. Orne also argued that them for misusing the concept of ecological validity, a psychologists err in treating human subjects as passive term coined by Egon Brunswik (e.g., 1955, 1956). -

The Effect of Using the Partners for Change Outcome Management System As Feedback Tool in Psychotherapy—A Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis

Psychotherapy Research ISSN: 1050-3307 (Print) 1468-4381 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tpsr20 The effect of using the Partners for Change Outcome Management System as feedback tool in psychotherapy—A systematic review and meta- analysis Ole Karkov Østergård, Hilde Randa & Esben Hougaard To cite this article: Ole Karkov Østergård, Hilde Randa & Esben Hougaard (2018): The effect of using the Partners for Change Outcome Management System as feedback tool in psychotherapy—A systematic review and meta-analysis, Psychotherapy Research, DOI: 10.1080/10503307.2018.1517949 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2018.1517949 Published online: 13 Sep 2018. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tpsr20 Psychotherapy Research, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2018.1517949 EMPIRICAL PAPER The effect of using the Partners for Change Outcome Management System as feedback tool in psychotherapy—A systematic review and meta-analysis OLE KARKOV ØSTERGÅRD , HILDE RANDA , & ESBEN HOUGAARD Department of Psychology and Behavioural Sciences, Aarhus University, Aarhus C, Denmark (Received 15 May 2018; revised 16 August 2018; accepted 16 August 2018) Abstract Objective: The aims of the study were to evaluate the effects of using the Partners for Change Outcome Management System (PCOMS) in psychotherapy and to explore potential moderators of the effect. Method: A comprehensive literature search including grey literature was conducted to identify controlled outcome studies on the PCOMS, randomized (RCTs), or non-randomized trials (N-RCT). Results: The literature search identified 18 studies, 14 RCTs, and four N-RCTs, including altogether 2910 participants. -

An Exploration of the Velten Mood Induction Procedure on Psychological Symptomology

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2007 An exploration of the Velten Mood Induction Procedure on psychological symptomology Carla Nanette Perlotto University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Perlotto, Carla Nanette, "An exploration of the Velten Mood Induction Procedure on psychological symptomology" (2007). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2729. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/y85c-lyne This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXPLORATION OF THE VELTEN MOOD INDUCTION PROCEDURE ON PSYCHOLOGICAL SYMPTOMOLOGY by Carla Nanette Perlotto Bachelor of Arts Chapman University 1993 Master of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2001 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Psychology Department of Psychology College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3261084 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Evidence Brief: Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures for Measurement Based Care in Mental Health Shared Decision-Making

Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Service Evidence-based Synthesis Program Evidence Brief: Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures for Measurement Based Care in Mental Health Shared Decision-Making Supplemental Materials November 2018 Prepared for: Investigators: Department of Veterans Affairs Kim Peterson, MS Veterans Health Administration Johanna Anderson, MPH Quality Enhancement Research Initiative Donald Bourne, MPH Health Services Research & Development Service Washington, DC 20420 Prepared by: Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP) Coordinating Center Portland VA Health Care System Portland, OR Mark Helfand, MD, MPH, MS, Director 4 Evidence Brief: Use of PROMs for MBC in Shared Decision-Making Evidence-based Synthesis Program TABLE OF CONTENTS Search Strategies ............................................................................................................................. 1 List of Excluded Studies ................................................................................................................. 8 Evidence Tables ............................................................................................................................ 14 Data Abstraction of Included Primary Studies .......................................................................... 14 Data Abstraction: Patient, Provider and Treatment Characteristics ...................................... 14 Data Abstraction: Intervention Characteristics ..................................................................... -

Understanding Variation in Reactions to Displays of Allegiance

Human Ethology Bulletin 32 (2017)1- Proc. of the XXIII Biennial ISHE Congress: 17-28 Research Article Understanding Variation in Reactions to Displays of Allegiance Daniel J. Kruger1, Michele Day2, Ailiya Duan2, Anna Heyblom2, Dora Juhasz2, Stephanie Misevich2, Camile Phaneuf2, Claire Saunders2, Peter Sonnega2 & Vibra Sreenivasa2 1 Population Studies Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 2 Literature, Science and Arts, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan [email protected] ABSTRACT Sports team rivalries involve expressions of evolved psychology related to in-group loyalty and inter-group competition. ESPN ranked the University of Michigan–Ohio State University football rivalry as the greatest North American sports rivalry. Toledo, Ohio is geographically closer to Ann Arbor, MI (UM), than to Columbus, OH (OSU) and conventional wisdom holds that team loyalty is divided among local residents. Previous observational research of thousands of individuals in Toledo indicated that no one simultaneously wore apparel from the two competing teams. Inspired by these observations, a second study examined reactions to displays of mixed loyalty vs. consistent loyalty. When a research confederate wore clothing featuring both UM and OSU, he elicited more attention and reactions than when wearing equivalent outfits featuring just one of the universities. The current study examines factors explaining individual differences in attention to displays of allegiance to rival groups, whether consistent or mixed. We made several predictions for explaining variation in reaction rates based on evolved coalitional psychology. We predicted that men, young adults in the typical undergraduate age range (18-25), and those wearing university merchandise themselves will have higher reaction rates to the confederate than women, individuals in other age groups, and individuals not wearing university merchandise respectively. -

A Review, Analysis, and Extension of the Job Demands-Control (-Support) Model

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2016 Work Stress: A Review, Analysis, and Extension of the Job Demands-Control (-Support) Model Marcus J. Fila Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Fila, Marcus J., "Work Stress: A Review, Analysis, and Extension of the Job Demands-Control (-Support) Model" (2016). Dissertations. 1620. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1620 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORK STRESS: A REVIEW, ANALYSIS, AND EXTENSION OF THE JOB DEMANDS-CONTROL (-SUPPORT) MODEL by Marcus J. Fila A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Educational Leadership, Research, and Technology Western Michigan University June 2016 Doctoral Committee: Joseph Kretovics, Ph.D., Chair Sue Poppink, Ph.D. Steve VanderVeen, Ph.D. WORK STRESS: A REVIEW, ANALYSIS, AND EXTENSION OF THE JOB DEMANDS-CONTROL (-SUPPORT) MODEL Marcus J. Fila, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Occupational stress and health literature is devoted to understanding and predicting the phenomenon of stress in the workplace, given its costly implications to individual and organizational health and well-being. The job demands-control (-support) (JDC(S)) model has been highly influential in occupational stress and health literature for over 37 years, and has been the theoretical foundation of more empirical studies than any other work stress model. -

Expectancy Effects and the Replicability of Behavioral

Perspectives on Psychological Science 7(6) 572 –584 Low Hopes, High Expectations: Expectancy © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Effects and the Replicability of Behavioral DOI: 10.1177/1745691612463704 Experiments http://pps.sagepub.com Olivier Klein1, Stéphane Doyen1,2, Christophe Leys1, Pedro A. Magalhães de Saldanha da Gama1, Sarah Miller1, Laurence Questienne1, and Axel Cleeremans1,2 1Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium, and 2Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique FRS-FNRS, Belgium Abstract This article revisits two classical issues in experimental methodology: experimenter bias and demand characteristics. We report a content analysis of the method section of experiments reported in two psychology journals (Psychological Science and the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology), focusing on aspects of the procedure associated with these two phenomena, such as mention of the presence of the experimenter, suspicion probing, and handling of deception. We note that such information is very often absent, which prevents observers from gauging the extent to which such factors influence the results. We consider the reasons that may explain this omission, including the automatization of psychology experiments, the evolution of research topics, and, most important, a view of research participants as passive receptacles of stimuli. Using a situated social cognition perspective, we emphasize the importance of integrating the social context of experiments in the explanation of psychological phenomena. We illustrate this argument via a controversy on stereotype-based behavioral priming effects. Keywords expectancy, demand characteristics, experimenter bias, replicability, methodology The application of what we think of as the scientific Since these seminal contributions, however, interest in such method has not simplified human behavior. -

Web-Based Administration of a Personality Questionnaire

Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 1999,31 (4), 572-577 Web-based administration ofa personality questionnaire: Comparison with traditional methods ROBERT N. DAVIS University ofMichigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan The World-Wide Web holds great promise as a meehanism for questionnaire-based research. But are data from Web-based questionnaires eomparable to data from standard paper-and-peneil question naires? This study assessed the equivalenee ofthe Ruminative Responses Seale in a Web-based format and in a paper-and-peneil format among introductory psyehology, upper-level psyehology, and non psyehology students. Internal eonsisteney eoefficients were eomparable aeross the groups. The par ticipants in the Web sample reported higherlevels of self-foeused rumination than did the othergroups. Women in the Web sample reported more self-foeused rumination than did women in the other groups. In the Websample, results did not eovary with aeeess loeation. These results suggest thatfindings from Web-based questionnaire research are eomparable with results obtained using standard proeedures. The eomputerized Web interface may also facilitate self-disclosure among research participants. The use ofcomputers in psychological assessment has have reported favorable results (e.g., Krantz, Ballard, & increased steadily over the last 30 years (Burke, 1992). Scher, 1997). For example, the results from one experi The advent ofthe World-Wide Web otTers unprecedented ment that was conducted both on the Web and in a labo opportunities for researchers to benefit from the use of ratory were nearly perfectly correlated (Krantz et al., computers in data collection (Schmidt, 1997; Smith & 1997). Although only a few published studies have ex Leigh, 1997). As a research medium, the Web offers re amined the equivalence question with respect to Web searchers at least four major benefits. -

Discuss the Extent to Which Psychology Is a Science

Parson: Study and Communication Skills for Psychology Chapter 13 – Sample Essay – Student 2 Discuss the extent to which Psychology is a Science. Psychologists use scientific methods, and when viewed from this perspective it is clear that Psychology does qualify as a science. This is due to the fact that scientific methods are the preferred method of investigation for the majority of psychologists. The most popular use of experiment are laboratory experiments in Psychology, as they offer the psychologist opportunities for control and prediction that are absent in less ‘scientific’ methods of investigation (Cardwell, Clark & Meldrum, 2004). There is also room for argument that some individual levels of Psychology are scientific in themselves. Psychology embraces explanations at different levels, ranging them from the physical to the sociological. Some levels of Psychology are widely acknowledged to be scientific, such as research into the Neuropsychology, Biopsychology, Cognitive Psychology and the study of mental illness (Buskist & Gerbing, 1990). The problem for Psychology occurs in the more social side of Psychology, where the dispute to scientific validity remains despite identical scientific methods being employed (Cardwell et al, 2004). However, while psychologists may well use scientific methods, such research has been criticised in terms of a lack of both internal and external validity. Due to ‘demand characteristics’ operating in a study, internal validity has been criticised (Cardwell et al, 2004). A demand characteristic is a feature of the experiment that invites predictable responses from the participants so that they do not behave as they normally would; they are cued to behave in a particular way due to the conditions of the experiment (Buskist & Gerbing, 1990).