Enabling Urban Poor Livelihoods Policy Making: Understanding the Role of Energy Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. Company Star

Fair Trade Enforcement Bureau-DTI Business Licensing and Accreditation Division LIST OF ACCREDITED SERVICE AND REPAIR SHOPS As of November 30, 2019 No. Star- Expiry Company Classific Address City Contact Person Tel. No. E-mail Category Date ation 1 (FMEI) Fernando Medical Enterprises 1460-1462 E. Rodriguez Sr. Avenue, Quezon City Maria Victoria F. Gutierrez - Managing (02)727 1521; marivicgutierrez@f Medical/Dental 31-Dec-19 Inc. Immculate Concepcion, Quezon City Director (02)727 1532 ernandomedical.co m 2 08 Auto Services 1 Star 4 B. Serrano cor. William Shaw Street, Caloocan City Edson B. Cachuela - Proprietor (02)330 6907 Automotive (Excluding 31-Dec-19 Caloocan City Aircon Servicing) 3 1 Stop Battery Shop, Inc. 1 Star 214 Gen. Luis St., Novaliches, Quezon Quezon City Herminio DC. Castillo - President and (02)9360 2262 419 onestopbattery201 Automotive (Excluding 31-Dec-19 City General Manager 2859 [email protected] Aircon Servicing) 4 1-29 Car Aircon Service Center 1 Star B1 L1 Sheryll Mirra Street, Multinational Parañaque City Ma. Luz M. Reyes - Proprietress (02)821 1202 macuzreyes129@ Automotive (Including 31-Dec-19 Village, Parañaque City gmail.com Aircon Servicing) 5 1st Corinthean's Appliance Services 1 Star 515-B Quintas Street, CAA BF Int'l. Las Piñas City Felvicenso L. Arguelles - Owner (02)463 0229 vinzarguelles@yah Ref and Airconditioning 31-Dec-19 Village, Las Piñas City oo.com (Type A) 6 2539 Cycle Parts Enterprises 1 Star 2539 M-Roxas Street, Sta. Ana, Manila Manila Robert C. Quides - Owner (02)954 4704 iluvurobert@gmail. Automotive 31-Dec-19 com (Motorcycle/Small Engine Servicing) 7 3BMA Refrigeration & Airconditioning 1 Star 2 Don Pepe St., Sto. -

1987 Philippine Constitution

THE 1987 CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES PREAMBLE We, the sovereign Filipino people, imploring the aid of Almighty God, in order to build a just and humane society, and establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promote the common good, conserve and develop our patrimony, and secure to ourselves and our posterity, the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law and a regime of truth, justice, freedom, love, equality, and peace, do ordain and promulgate this Constitution. ARTICLE I NATIONAL TERRITORY The national territory comprises the Philippine archipelago, with all the islands and waters embraced therein, and all other territories over which the Philippines has sovereignty or jurisdiction, consisting of its terrestrial, fluvial and aerial domains, including its territorial sea, the seabed, the subsoil, the insular shelves, and other submarine areas. The waters around, between, and connecting the islands of the archipelago, regardless of their breadth and dimensions, form part of the internal waters of the Philippines. ARTICLE II DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLES AND STATE POLICIES PRINCIPLES Section 1. The Philippines is a democratic and republican State. Sovereignty resides in the people and all government authority emanates from them. Section 2. The Philippines renounces war as an instrument of national policy, adopts the generally accepted principles of international law as part of the law of the land and adheres to the policy of peace, equality, justice, freedom, cooperation, and amity with all nations. Section 3. Civilian authority is, at all times, supreme over the military. The Armed Forces of the Philippines is the protector of the people and the State. -

City Atm Name Address Banking Schedule Edsa

METRO MANILA CITY ATM NAME ADDRESS BANKING SCHEDULE CALOOCAN EDSA BALINTAWAK Ground Floor, PPI Bldg., 355 EDSA cor. Gen. Tirona Street, Brgy. Balintawak Caloocan City 24/7 MONUMENTO Samson Road near cor. Araneta Ave., Brgy. 77, Caloocan City 24/7 MONUMENTO CIRCLE 357 A. Bonifacio Circle, Bgy 86 Monumento, Caloocan City 24/7 LAS PIÑAS Mondays to Fridays ALMANZA G/F D'Marrchs Bldg, Alabang - Zapote Road, Brgy Almanza Uno, Las Pinas City 1740 9:00 am to 4:30 pm ALMANZA UNO-LAS PIÑAS Macro Golden Star Bldg, Alabang Zapote Road Brgy Almanza Uno, Las Pinas City 1740 24/7 Mondays to Fridays FAMILY BANK BF RESORT BF Resort Drive cor. Gloria Diaz St., BF Resort Village, Barangay Talon Dos, Las Pinas 9:00 am to 4:30 pm FAMILY BANK LAS PIÑAS NAGA ROAD No 145 Lot 1B Naga Road Pulang Lupa Dos Las Pinas City 24/7 FAMILY BANK LAS PIÑAS PAMPLONA TRES Real St., Alabang Zapote Road, Brgy Pamplona Tres, Las Pinas City 1740 24/7 Mondays to Fridays LAS PIÑAS Real St. cor. Gemini St., Brgy Pamplona Dos, Las Pinas City 1740 9:00 am to 4:30 pm LAS PIÑAS CITADELLA Unit 1B Fenina Bldg., 6750 CAA Road corner Cittadella Village, Brgy. Pulang Lupa Dos, Las Pinas City 24/7 PILAR VILLAGE LAS PIÑAS 27 Rose Avenue, Pilar Village, Barangay Pilar Village, Las Pinas City 24/7 Mondays to Fridays SM SOUTHMALL Upper Ground Floor, SM Southmall, Alabang Zapote Road, Brgy Almanza Uno, Las Pinas City 1740 10:00 am to 6:00 pm MAKATI ALFARO 2 G/F LPL Center, 130 L.P. -

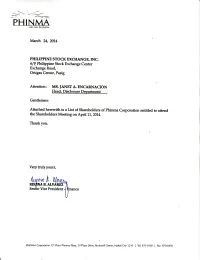

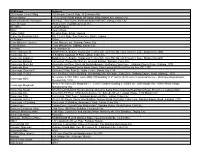

Hilfi,,,Ful Rt, W Flinance

J\N V-/----/- Life an be l>etter March 24,2014 PHILIPPINE STOCK EXCHANGE, INC. /F Philippine Stock Exchange Center Exdrange Road, Ortigas Center, Pasig Attention: MS.IANETA-ENCARNACION Head, Disclosure Depa@ent Genflemen: Attached herewith is a List of Shareholders of Phinma Coqporation entitled to attend the Shareholders Meeting on April 11.',ZOl4. Thankyou. Verytrulyyours, hilfi,,,ful rt, W REqfNA B. Senior Vice ^LvirREYt4\\President flinance PH|NMACorporationl2eFloorPhinmaPlaza,3gPlazaOrive,nockwell Center,Makati City1210 lTel:870-0100 lFax:870-0456 Stock Transfer Service Inc. Page No. 1 PHINMA CORPORATION Stockholder MasterList As of 03/18/2014 Sth. No. Name Address Citizenship Holdings ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 0090000083 YU, JUAN G. &/OR YU JOHN PETER C. 12 WALL ST. Filipino 35,000 DONA RITA VILLAGE BANILAD, CEBU CITY 000AI203 EDENCIO ABAN NO ADDRESS Filipino 443 000AI055 GABRIEL M. ABEDES QUIRINO, BACNOTAN Filipino 1,342 LA UNION 000AI363 JUAN BOSCO P. ABELLANA MT. CARMEL PARISA RD. 8 Filipino 252 PROJECT 6, QUEZON CITY 000AI171 ARTURO G. ABELLO C/O RAFAEL ABELLO SR. Filipino 4,704 PUROK ROXAS, TANGUB BACOLOD CITY 000AI366 CARLOS ABELLO C/O JOSE SANTOS Filipino 100 ADM BLDG. ATENEO DE MANILA UNIVERSITY KATIPUNAN AVE. QUEZON CITY 000AI341 EDUARDO G. ABELLO &/OR MARILEN P. ABELLO 206 MARIA PATERNO Filipino 3,317 SAN JUAN, METRO MANILA 000AI333 ELISA G. ABELLO 206 M. PATERNO ST. Filipino 1,804 SAN JUAN, METRO MANILA 000AI00C EMILIO ABELLO 206 M. PATERNO ST. Filipino 2,704 SAN JUAN, METRO MANILA 000AI063 MANUEL ABELLO 1725 BALBOA STREET Filipino 1,500 ERORECO VILLAGE BACOLOD CITY 000AI108 MANUEL G. ABELLO 699 BUFFALO, GREENHILLS Filipino 1,375 MANDALUYONG CITY 000AI167 PACITA G. -

Paylink Merchants 2005

LIST OF AFFILIATED MERCHANTS Count Merchant No. Legal Name DBA Name Address1 Address 2 City Area Code / Desc 1 181933 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (ALABANG) TIERRA NUEVA SUBD. ALABANG MUNTINLUPA 33 - MUNTINLUPA 2 1117761 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (BULACAN) IS PAVILIONS MEYCAUAYAN 58 - BULACAN 3 181834 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (CALOOCAN) RIZAL AVE. EXT. CALOOCAN CALOOCAN CITY 28 - CALOOCAN 4 1117167 WALTER MART STA ROSA, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (DASMARINAS) WALTERMART, KM 30 BO BUROL AGUINALDO DASMARINAS 59 - CAVITE 5 290288 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (ERMITA) 3/F ROBINSONS PLACE ERMITA MANILA 20 - MANILA 6 231852 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (EVER ORTIGA G/F EVER GOTESCO ORTIGAS AVE., STA. LUCIA, PASIG CITY PASIG CITY 25 - PASIG 7 231878 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (FARMER'S) FARMER'S PLAZA CUBAO QUEZON CITY 21 - QUEZON CITY 8 182485 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (GALLERIA) ORTIGAS AVE., QUEZON CITY QUEZON CITY 21 - QUEZON CITY 9 182469 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (GREENHILLS) UNIMART SUPERMART GREENHILLS SAN JUAN, METRO MANILA SAN JUAN 23 - SAN JUAN 10 181917 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (HARRISON) 1ST FLR. HARRISON PLAZA COMML. VITO CRUZ, MALATE MANILA 20 - MANILA 11 182501 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (LAS PINAS) 269 ALABANG ZAPOTE ROAD PAMPLONA LAS PINAS 32 - LAS PINAS 12 289397 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (METROPOLIS) G/F MANUELA METROPOLIS ALABANG MUNTINLUPA 33 - MUNTINLUPA 13 181875 ABENSON INCORPORATED ABENSON - PAYLINK (QUAD) QUAD I, MCC . MAKATI CITY 22 - MAKATI 14 181768 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (SHERIDAN) 11 SHERIDAN ST., MANDALUYONG MANDALUYONG 24 - MANDALUYONG 15 181859 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (SM CITY) SM CITY NORTH EDSA QUEZON CITY QUEZON CITY 21 - QUEZON CITY 16 181784 ABENSON, INC. -

APM Name Address 350 Arcade Comm'l Bldg 350 Arcade Comm'l Bldg, 15 Sunflower Rd Atrium Makati 1773 CGII-ATRIUM Makati GF Atrium Bldg

APM Name Address 350 Arcade Comm'l Bldg 350 Arcade Comm'l Bldg, 15 Sunflower Rd Atrium Makati 1773 CGII-ATRIUM Makati GF Atrium Bldg. Makati Ave, Makati City Author Solutions TGU tower 6th Floor, TGU Tower, Asiatown Business Park, Lahug, Cebu City Azure Bicutan West service road Bicutan Exit slex BC Office Lopez Building Black Asun's House Caltex SLEX S Luzon Expy, Biñan, Laguna Caltex Southwoods (nav) Blk. 7 Lot 9 Brgy. San Francisco, Biñan, Laguna CCN (Nav) Office Cebu Mitsumi- Canteen Cebu Mitsumi, Inc. Sabang, Danao City Cebu-Mitsumi Cebu Mitsumi Inc, Sabang, Danao City City Hall F.B. Harrison St. Converg Baguio B Building No A, Baguio- AyalaLand TechnoHub, John Hay Special Economic Zone, Baguio City 2600 Convergys - i2 i2 Building, Asiatown IT Park, Lahug, Cebu City Convergys baguio A Building No A, Baguio- AyalaLand TechnoHub, John Hay Special Economic Zone, Baguio City 2600 Convergys Banawa Convergys, Paseo San Ramon, Arcenas Estates, Banawa, Cebu City Convergys Block 44 Ground to 3rd Floor, Block 44 Northbridgeway, Northgate Cyberzone. , Alabang Zapote Road, Alabang, 1770 Convergys Eton 7F, Three Cyberpod Centris North Tower, Eton Centris EDSA cor Quezon Ave. QC 1100 Convergys Glorietta 5 Glorietta 5 Bldg. East St., Ayala Center, Makati City 1224 Convergys I Hub 2 6th - 9th Floor, IHub 2 Building, Northbridgeway, Northgate Cyberzone, Alabang-Zapote Road, Alabang, 1770 Mezzanine & 10th 19th Floors, MDC 100 Building, C.P. Garcia (C-5) corner Eastwood Avenue, Barangay Bagumbayan, Convergys MDC Quezon City, 1110 8th to 11th Floors SM Megamall I.T. Center, Carpark Building C, EDSA cor. Julia Vargas Ave., Wack-Wack Village, Convergys Megamall Mandaluyong City Convergys Nuvali One Evotech Building Nuvali Lakeside Evozone Santa Rosa-Tagaytay Road Santa Rosa, Province of Laguna 4026 Convergys One Ground to 8th Floor, 6796 Ayala Avenue cor. -

CONSTITUTION of the REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES Document Date: 1986

Date Printed: 01/14/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 29 Tab Number: 37 Document Title: THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Document Date: 1986 Document Country: PHI Document Language: ENG IFES 10: CON00159 Republic of the Philippines The Constitutional Commission of 1986 The- Constitution ,- of.the- -Republic of tile Philippines Adopted by , - . THE CONSTITIJTIONAL COMMISSION OF 1986 At the National Government-Center, Quezon City, Philjppincs, on the fifteenth day of October, Nineteen hundred and eighty-six 198(j THE CONSTITUTION· OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES P REAM B LE. We; toe sovereign Filipino people, imploring the aid of Almighty Cod, in order to build a just and humane society and establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promotl' the common good, conserve and. develop· our patrimony, and secure- to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law"and a regime of truth, justice, free dom, love, equality, and peace, do ordain and piomulgatethis Consti tution. ARTICLE I NATIONAL TERRITORY The national territorycomprise~ the Philippine archipelago, with all the islands and waters embraced therein,' and all other territories over which the. Philippines has sovereignty or jurisdiction, .consisting of its terrestrial, fluvial, and aerial domains, including its territorial sea, the seabed, the subsoil, the insula~ shelves, and other submarine areas. The waters aroilnd, between, and connecting the islands of the archipelago, regardless of their breadth and. dimensions, form part of the internal waters of the Philippines. ARTICLE II r DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLE15 AND STATE POLICIES PRINCIPLES Section I .. The Philippines is a democratic and· republican State. -

Metro Manila Infrastructure Development

Republic of the Philippines Department of Public Works and Highways URBAN ROAD PROJECTS OFFICE Metro Manila Infrastructure Development CARLOS G. MUTUC Project Director URBANURBAN ROADROAD PROJECTSPROJECTS OFFICEOFFICE URPOURPO isis aa specialspecial projectproject officeoffice responsibleresponsible forfor thethe formulationformulation andand developmentdevelopment ofof allall projectsprojects inin urbanurban areas,areas, particularlyparticularly inin MetroMetro Manila,Manila, financedfinanced byby JBIC,JBIC, WBWB andand ADB.ADB. ItIt alsoalso implementsimplements highlyhighly complexcomplex projectsprojects financedfinanced byby GOP.GOP. URPOURPO’s’s mainmain tasktask isis toto ensureensure aa moremore effectiveeffective andand expedientexpedient implementationimplementation ofof projectsprojects gearedgeared towardstowards completioncompletion ofof thethe MetroMetro ManilaManila MajorMajor RoadRoad NetworkNetwork System.System. URBANURBAN ROADROAD PROJECTSPROJECTS OFFICEOFFICE I STRATEGYSTRATEGYI -- addressaddress criticalcritical bottlenecksbottlenecks andand alleviatealleviate traffictraffic congestioncongestion inin MetroMetro Manila.Manila. GOALSGOALS -- completecomplete thethe MMMM roadroad networknetwork systemsystem -- constructconstruct interchangesinterchanges atat majormajor intersectionsintersections -- constructconstruct secondarysecondary roadsroads toto complementcomplement thethe MMMM RoadRoad NetworkNetwork -- rehabilitaterehabilitate primary/secondaryprimary/secondary roadsroads -- establishestablish aa validvalid urbanurban -

( Mabuhay Lanes ) Alternate Routes for EDSA

Republic of the Philippines Office of the President Alternate Routes for EDSA ( Mabuhay Lanes ) Alternate Routes For EDSA MABUHAY LANES for Private Vehicles from North to South Route 1: From Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA): Turn right at West Avenue, right at Quezon Avenue, U-turn near Magbanua, right at Timog, right at T. Morato, right at E. Rodriguez, left at Gilmore, straight to Granada , right to Santolan Road or right at N. Domingo, left at Pinaglabanan, right at P. Guevarra, left at L. Mencias, right at Shaw Blvd., left at Acacia Lane, right at F. Ortigas, left at P. Cruz, left at F. Blumentrit, left at Coronado, take Mandaluyong - Makati Bridge to destination. Route 1a: From Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA): Turn right at Scout Borromeo, left at Scout Ybardolaza / Scout Torillo / Scout T. Morato / Scout Tuazon or Scout Tobias, right at E. Rodriguez, left at Gilmore, straight to Granada , right to Santolan Road or right at N. Domingo, left at Pinaglabanan, right at P. Guevarra, left at L. Mencias, right at Shaw Blvd., left at Acacia Lane, right at F. Ortigas, left at P. Cruz, left at F. Blumentrit, left at Coronado, take Mandaluyong - Makati Bridge to destination. Route 2: From Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA): Turn right at West Avenue, right at Del Monte Ave., left at Sto. Domingo or Biak na Bato, right at Amoranto , left at Banawe or D. Tuazon, right at Maria Clara or Dapitan to destination. Route 3: From North Luzon Expressway : Exit at Mindanao Avenue Access Ramp, right at Mindanao Ave., left at Congressional, right at Luzon Avenue, take Bridge crossing Commonwealth Avenue, Katipunan Avenue, C-5 to destination. -

PORT of MANILA - Bls with No Entries As of July 5, 2021 Actual Cargo Arrival Date of July 2-4, 2021

PORT OF MANILA - BLs with No Entries as of July 5, 2021 Actual Cargo Arrival Date of July 2-4, 2021 ACTUAL DATE ACTUAL DATE OF No. CONSIGNEE/NOTIFY PARTY CONSIGNEE ADDRESS REGNUM BL DESCRIPTION OF ARRIVAL DISCHARGED 10TH AND 11TH FLOORS THE FINANCE CENTRE 26TH CORNER 9TH PART OF 1X40 CTNR 7 PACKAGES STC OFFICE AND 1 3M PHILIPPINES INC 7/4/2021 7/4/2021 APL0073-21 SIN210757896 AVENUE LABORATORY SUPPLIES HS CODE 350691 BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY TAGUIG METRO MANILA 1634 PHILIPPINES 10TH AND 11TH FLOORS THE FINANCE CENTRE 26TH CORNER 9TH PART OF 1X40 CTNR 1 PACKAGE STC OFFICE AND 2 3M PHILIPPINES INC 7/4/2021 7/4/2021 APL0073-21 SIN210762820 AVENUE LABORATORY SUPPLIES HS CODE 630710 BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY TAGUIG METRO MANILA 1634 PHILIPPINES 10TH AND 11TH FLOORS THE FINANCE CENTRE 26TH CORNER 9TH PART OF 1X20 CTNR 1 PACKAGE STC OFFICE AND 3 3M PHILIPPINES INC 7/4/2021 7/4/2021 APL0073-21 SIN210725529 AVENUE LABORATORY SUPPLIES HS CODE 391910 BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY TAGUIG METRO MANILA 1634 PHILIPPINES 10TH AND 11TH FLOORS THE FINANCE CENTRE 26TH CORNER 9TH PART OF 1X20 CTNR 2 PACKAGES STC OFFICE AND 4 3M PHILIPPINES INC 7/4/2021 7/4/2021 APL0073-21 SIN210762824 AVENUE LABORATORY SUPPLIES HS CODE 960390 BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY TAGUIG METRO MANILA 1634 PHILIPPINES 10TH AND 11TH FLOORS THE FINANCE 1X20 CTNR 7 PACKAGES STC 17002 6 SML UTILITY HOOKS MP CENTRE 26TH CORNER 9TH 5 3M PHILIPPINES INC 7/4/2021 7/4/2021 APL0073-21 SIN210767819 17006ANZ MINI HOOKS 17081ANZ DESIGNER MED HOOK AND AVENUE ETC HS CODE 39269099 39249090 39199099 BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY -

No. Company Star

Fair Trade Enforcement Bureau-DTI Business Licensing and Accreditation Division LIST OF ACCREDITED SERVICE AND REPAIR SHOPS As of January 31, 2020 No. Star- Expiry Company Classific Address City Contact Person Tel. No. E-mail Category Date ation 1 1-29 Car Aircon Service Center 1 Star Blk 1 Lot 1, Sheryll Mirra Street, Parañaque City Ma. Luz M. Reyes - Proprietress (02)8821 1202 maluzreyes129@g Automotive (Including 31-Dec-20 Multinational Village, Parañaque City mail.com Aircon Servicing) 2 1st Corinthean's Appliance Services 1 Star 515-B Quintas Street, CAA BF Int'l. Las Piñas City Felvicenso L. Arguelles - Owner (02)463 0229 vinzarguelles@yah Ref and Airconditioning 31-Dec-20 Village, Las Piñas City oo.com (Type A) 3 2 + 1 Electronics Repair Shop 1 Star Unit 1 MOQ Building, Escoda Street, Parañaque City Emilia L. Manalang - Owner (02)8809 4517 Electronics 31-Dec-20 Phase 1 BF Homes, Parañaque City 4 2539 Cycle Parts Enterprises 1 Star 2539 M. Roxas St., Sta. Ana, Manila Manila Rober C. Quides - Owner (02)7954 4704 Automotive 31-Dec-20 (Motorcycle/Small Engine Servicing) 5 5 Jay Machine Shop 1 Star 2125 G. Tuazon Street, Sampaloc, Manila Thelma R. Germina - Owner (02)501 3137 fivejay_machinesh Machine Shop 31-Dec-20 Manila [email protected] 6 5-J Airconditioning Services 1 Star 9 Alfonso Street, Brgy. Rosario, Pasig Pasig City Edgar L. Sambajon Jr. - Technician (+63)0929 977 None Automotive (Including 31-Dec-20 City and Owner 4974 Aircon Servicing) 7 A.B. Joyce Electronic Service 1 Star Stall C-40-520, P. -

SHELL PHILIPPINES LIST of STATIONS OFFERING DISCOUNTS to Puvs AS of JUNE 30, 2019

SHELL PHILIPPINES LIST OF STATIONS OFFERING DISCOUNTS TO PUVs AS OF JUNE 30, 2019 Site Name STATION ADDRESS Product SH EDSA CALOOCAN QC BOUND COSS. 472 EDSA CALOOCAN CITY FS ADO SH EDSA CALOOCAN QC BOUND COSS. 472 EDSA CALOOCAN CITY FS Gas SH EDSA CALOOCAN QC BOUND COSS. 472 EDSA CALOOCAN CITY VPN+ SH 8TH 9TH AVE B SERRANO COSS. 67 B. SERRANO ST BRGY 108 CALOOCAN CITY FS ADO SH 8TH 9TH AVE B SERRANO COSS. 67 B. SERRANO ST BRGY 108 CALOOCAN CITY FS Gas SH 8TH 9TH AVE B SERRANO COSS. 67 B. SERRANO ST BRGY 108 CALOOCAN CITY VPN+ SH UNITED NATIONS PEREZ COSS. U.N. AVE. COR. PEREZ ST., PACO, MANILA FS Gas SH UNITED NATIONS PEREZ COSS. U.N. AVE. COR. PEREZ ST., PACO, MANILA VPN+ SH EDSA BANSALANGIN QC COSS. 1015 EDSA COR BANSALANGIN ST BRGY VETERANS VILL QUEZON CITY FS ADO SH EDSA BANSALANGIN QC COSS. 1015 EDSA COR BANSALANGIN ST BRGY VETERANS VILL QUEZON CITY FS Gas SH EDSA BANSALANGIN QC COSS. 1015 EDSA COR BANSALANGIN ST BRGY VETERANS VILL QUEZON CITY VPN+ SH A BONIFACIO BINUANG COSS 185 A. BONIFACIO AVE., COR. BINUANG ST., N.S. AMORANTO QUEZON CITY FS ADO SH A BONIFACIO BINUANG COSS 185 A. BONIFACIO AVE., COR. BINUANG ST., N.S. AMORANTO QUEZON CITY FS Gas SH A BONIFACIO BINUANG COSS 185 A. BONIFACIO AVE., COR. BINUANG ST., N.S. AMORANTO QUEZON CITY VPN+ SH MCARTHUR TINAJEROS COSS. MC ARTHUR HIWAY CORNER UNIV AVE POTRERO, MALABON CITY FS ADO SH MCARTHUR TINAJEROS COSS. MC ARTHUR HIWAY CORNER UNIV AVE POTRERO, MALABON CITY FS Gas SH MCARTHUR TINAJEROS COSS.