What Clinical Features Are Most Useful to Distinguish Definite Multiple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper Motor Neuron Dominant Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia

brain sciences Review Upper Motor Neuron Disorders: Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper Motor Neuron Dominant Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Timothy Fullam and Jeffrey Statland * Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas, KS 66160, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Following the exclusion of potentially reversible causes, the differential for those patients presenting with a predominant upper motor neuron syndrome includes primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP), or upper motor neuron dominant ALS (UMNdALS). Differentiation of these disorders in the early phases of disease remains challenging. While no single clinical or diagnostic tests is specific, there are several developing biomarkers and neuroimaging technologies which may help distinguish PLS from HSP and UMNdALS. Recent consensus diagnostic criteria and use of evolving technologies will allow more precise delineation of PLS from other upper motor neuron disorders and aid in the targeting of potentially disease-modifying therapeutics. Keywords: primary lateral sclerosis; amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; hereditary spastic paraplegia Citation: Fullam, T.; Statland, J. Upper Motor Neuron Disorders: Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper 1. Introduction Motor Neuron Dominant Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) and Wilhelm Erb (1840–1921) are credited with first Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and describing a distinct clinical syndrome of upper motor neuron (UMN) tract degeneration in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia. Brain isolation with symptoms including spasticity, hyperreflexia, and mild weakness [1,2]. Many Sci. 2021, 11, 611. https:// of the earliest described cases included cases of hereditary spastic paraplegia, amyotrophic doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050611 lateral sclerosis, and underrecognized structural, infectious, or inflammatory etiologies for upper motor neuron dysfunction which have since become routinely diagnosed with the Academic Editors: P. -

Management of Neurogenic Dysphagia

694 Postgrad Med J 2001;77:694–699 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.77.913.694 on 1 November 2001. Downloaded from Management of neurogenic dysphagia A M O Bakheit Dysphagia is common in patients with neuro- of the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, brain logical disorders. It may result from lesions in stem, cerebellum, and lower cranial nerves may the central or peripheral nervous system as well result in dysphagia. Degeneration of the as from diseases of muscle and disorders of the myenteric ganglion cells in the oesophagus, neuromuscular junction. Drugs that are com- muscle diseases and disorders of neuromusc- monly used in the management of neurological ular transmission, for example myasthenia conditions may also precipitate or aggravate gravis and Eaton-Lambers syndrome, are other swallowing diYculties in some patients. Neuro- less common causes. genic dysphagia often results in serious compli- cations, including pulmonary aspiration, dehy- CEREBRAL CORTEX dration, and malnutrition. These The commonest condition associated with complications are usually preventable if the dysphagia resulting from cortical lesions is stroke. Acute stroke is complicated by dys- dysphagia is recognised early and managed 1 appropriately. phagia in about 25%–42% of all cases. Dysphagia in these patients is usually associ- Physiological mechanisms of neurogenic ated with hemiplegia due to lesions of the brain stem or the involvement of one or both dysphagia The act of swallowing may be viewed as three hemispheres. However, on rare occasions, dys- discrete but inter-related physiological stages: phagia may be the sole manifestation of a cer- the oral, pharyngeal, and oesophageal phases. -

Diagnostic Clues in Multiple System Atrophy

DO I:10.4274/Tnd.82905 Case Report / Olgu Sunumu Diagnostic Clues in Multiple System Atrophy: A Case Report and Literature Review Multisistem Atrofi Tanısında İpuçları: Bir Olgu Sunumu ve Literatürün Gözden Geçirilmesi Mehmet Yücel, Oğuzhan Öz, Hakan Akgün, Semai Bek, Tayfun Kaşıkçı, İlter Uysal, Yaşar Kütükçü, Zeki Odabaşı Gülhane Military Medical Academy, Ankara, Turkey Sum mary Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is an adult-onset, sporadic, progressive neurodegenerative disease. Based on the consensus criteria, patients with MSA are clinically classified into cerebellar (MSA-C) and parkinsonian (MSA-P) subtypes. In addition to major diagnostic criteria including poor response to levodopa, and presence of pyramidal or cerebellar signs (ataxia) or autonomic failure, certain clinical features or ‘‘red flags’’ may raise the clinical suspicion for MSA. In our case report we present a 67-year-old female patient admitted to our hospital due to inability to walk, with poor response to levodopa therapy, whose neurological examination revealed severe Parkinsonism, ataxia and who fulfilled all criteria for MSA, as rarely seen in clinical practice.(Turkish Journal of Neurology 2013; 19:28-30) Key Words: Multiple system atrophy, autonomic failure, diagnostic criteria Özet Multisistem atrofi (MSA) erişkin dönemde başlayan, ilerleyici, nedeni bilinmeyen sporadik nörodejeneratif bir hastalıktır. MSA kabul görmüş tanı kriterlerine göre klinik olarak serebellar (MSA-C) ve parkinsoniyen (MSA-P) alt tiplerine ayrılmaktadır. Düşük levadopa yanıtı, piramidal, serebellar bulguların (ataksi) ya da otonomik bozukluk olması gibi majör tanı kriterlerininin yanında “red flags” olarak isimlendirilen belirgin klinik bulgular ya da uyarı işaretlerinin olması MSA tanısı için klinik şüpheyi oluşturmalıdır. Olgu sunumunda 67 yaşında yürüyememe şikayeti ile polikliniğimize müracaat eden ve levadopa tedavisine düşük yanıt gösteren ciddi parkinsonizm bulguları ile ataksi bulunan kadın hasta MSA tanı kriterlerini tam olarak karşıladığı ve klinik pratikte nadir görüldüğü için sunduk. -

Hereditary Ataxia Multigene Panel Testing

Lab Management Guidelines V1.0.2021 Hereditary Ataxia Multigene Panel Testing MOL.TS.310.A v1.0.2021 Introduction Hereditary Ataxia Multigene Panel testing is addressed by this guideline. Procedures addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedures addressed by this Procedure codes guideline Hereditary Ataxia Multigene Panel 81443 (including sequencing of at least 15 genes) Genomic Unity Ataxia Repeat Expansion 0216U and Sequence Analysis Genomic Unity Comprehensive Ataxia 0217U Repeat Expansion and Sequence Analysis Unlisted molecular pathology procedure 81479 What are hereditary ataxias Definition The hereditary ataxias are a group of genetic disorders. They are characterized by slowly progressive uncoordinated, unsteady movement and gait, and often poor coordination of hands, eye movements, and speech. Cerebellar atrophy is also frequently seen.1 Incidence and prevalence Prevalence estimates vary. The prevalence of autosomal dominant ataxias is approximately 1-5:100,000.1 One study in Norway estimated the prevalence of hereditary ataxia at 6.5 per 100,000 people.2 © 2020 eviCore healthcare. All Rights Reserved. 1 of 8 400 Buckwalter Place Boulevard, Bluffton, SC 29910 (800) 918-8924 www.eviCore.com Lab Management Guidelines V1.0.2021 Symptoms Although hereditary ataxias are made up of multiple different conditions, they are characterized by slowly progressive uncoordinated, unsteady movement and gait, and often poor coordination of hands, eye movements, and speech. Cerebellar atrophy is also frequently seen.1 Cause Hereditary ataxias are caused by mutations in one of numerous genes. -

Multiple System Atrophy

Multiple System Atrophy U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service National Institutes of Health Multiple System Atrophy What is multiple system atrophy? ultiple system atrophy (MSA) is M a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a combination of symptoms that affect both the autonomic nervous system (the part of the nervous system that controls involuntary action such as blood pressure or digestion) and move- ment. The symptoms reflect the progressive loss of function and death of different types of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. Symptoms of autonomic failure that may be seen in MSA include fainting spells and prob- lems with heart rate, erectile dysfunction, and bladder control. Motor impairments (loss of or limited muscle control or movement, or limited mobility) may include tremor, rigidity, and/or loss of muscle coordination as well as difficulties with speech and gait (the way a person walks). Some of these features are similar to those seen in Parkinson’s disease, and early in the disease course it often may be difficult to distinguish these disorders. MSA is a rare disease, affecting potentially 15,000 to 50,000 Americans, including men and women and all racial groups. Symptoms tend to appear in a person’s 50s and advance rapidly over the course of 5 to 10 years, with progressive loss of motor function and 1 eventual confinement to bed. People with MSA often develop pneumonia in the later stages of the disease and may suddenly die from cardiac or respiratory issues. While some of the symptoms of MSA can be treated with medications, currently there are no drugs that are able to slow disease progression and there is no cure. -

ICD9 & ICD10 Neuromuscular Codes

ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM NEUROMUSCULAR DIAGNOSIS CODES ICD-9-CM ICD-10-CM Focal Neuropathy Mononeuropathy G56.00 Carpal tunnel syndrome, unspecified Carpal tunnel syndrome 354.00 G56.00 upper limb Other lesions of median nerve, Other median nerve lesion 354.10 G56.10 unspecified upper limb Lesion of ulnar nerve, unspecified Lesion of ulnar nerve 354.20 G56.20 upper limb Lesion of radial nerve, unspecified Lesion of radial nerve 354.30 G56.30 upper limb Lesion of sciatic nerve, unspecified Sciatic nerve lesion (Piriformis syndrome) 355.00 G57.00 lower limb Meralgia paresthetica, unspecified Meralgia paresthetica 355.10 G57.10 lower limb Lesion of lateral popiteal nerve, Peroneal nerve (lesion of lateral popiteal nerve) 355.30 G57.30 unspecified lower limb Tarsal tunnel syndrome, unspecified Tarsal tunnel syndrome 355.50 G57.50 lower limb Plexus Brachial plexus lesion 353.00 Brachial plexus disorders G54.0 Brachial neuralgia (or radiculitis NOS) 723.40 Radiculopathy, cervical region M54.12 Radiculopathy, cervicothoracic region M54.13 Thoracic outlet syndrome (Thoracic root Thoracic root disorders, not elsewhere 353.00 G54.3 lesions, not elsewhere classified) classified Lumbosacral plexus lesion 353.10 Lumbosacral plexus disorders G54.1 Neuralgic amyotrophy 353.50 Neuralgic amyotrophy G54.5 Root Cervical radiculopathy (Intervertebral disc Cervical disc disorder with myelopathy, 722.71 M50.00 disorder with myelopathy, cervical region) unspecified cervical region Lumbosacral root lesions (Degeneration of Other intervertebral disc degeneration, -

History-Of-Movement-Disorders.Pdf

Comp. by: NJayamalathiProof0000876237 Date:20/11/08 Time:10:08:14 Stage:First Proof File Path://spiina1001z/Womat/Production/PRODENV/0000000001/0000011393/0000000016/ 0000876237.3D Proof by: QC by: ProjectAcronym:BS:FINGER Volume:02133 Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 95 (3rd series) History of Neurology S. Finger, F. Boller, K.L. Tyler, Editors # 2009 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved Chapter 33 The history of movement disorders DOUGLAS J. LANSKA* Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tomah, WI, USA, and University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, USA THE BASAL GANGLIA AND DISORDERS Eduard Hitzig (1838–1907) on the cerebral cortex of dogs OF MOVEMENT (Fritsch and Hitzig, 1870/1960), British physiologist Distinction between cortex, white matter, David Ferrier’s (1843–1928) stimulation and ablation and subcortical nuclei experiments on rabbits, cats, dogs and primates begun in 1873 (Ferrier, 1876), and Jackson’s careful clinical The distinction between cortex, white matter, and sub- and clinical-pathologic studies in people (late 1860s cortical nuclei was appreciated by Andreas Vesalius and early 1870s) that the role of the motor cortex was (1514–1564) and Francisco Piccolomini (1520–1604) in appreciated, so that by 1876 Jackson could consider the the 16th century (Vesalius, 1542; Piccolomini, 1630; “motor centers in Hitzig and Ferrier’s region ...higher Goetz et al., 2001a), and a century later British physician in degree of evolution that the corpus striatum” Thomas Willis (1621–1675) implicated the corpus -

Deep Brain Stimulation in the Treatment of Dyskinesia and Dystonia

Neurosurg Focus 17 (1):E2, 2004, Click here to return to Table of Contents Deep brain stimulation in the treatment of dyskinesia and dystonia HIROKI TODA, M.D., PH.D., CLEMENT HAMANI, M.D., PH.D., AND ANDRES LOZANO, M.D., PH.D., F.R.C.S.(C) Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Toronto Western Hospital, University of Toronto, Ontario, Cananda Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has become a mainstay of treatment for patients with movement disorders. This modality is directed at modulating pathological activity within basal ganglia output structures by stimulating some of their nuclei, such as the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and the globus pallidus internus (GPi), without making permanent lesions. With the accumulation of experience, indications for the use of DBS have become clearer and the effective- ness and limitations of this form of therapy in different clinical conditions have been better appreciated. In this review the authors discuss the efficacy of DBS in the treatment of dystonia and levodopa-induced dyskinesias. The use of DBS of the STN and GPi is very effective for the treatment of movement disorders induced by levodopa. The relative ben- efits of using the GPi as opposed to the STN as a target are still being investigated. Bilateral GPi stimulation is gain- ing importance in the therapeutic armamentarium for the treatment of dystonia. The DYT1 forms of generalized dys- tonia and cervical dystonias respond to DBS better than secondary dystonia does. Discrimination between the diverse forms of dystonia and a better understanding of the pathophysiological features of this condition will serve as a plat- form for improved outcomes. -

THE SYNDROMES of the ARTERIES of the BRAIN and SPINAL CORD Part 1 by LESLIE G

65 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.29.328.65 on 1 February 1953. Downloaded from THE SYNDROMES OF THE ARTERIES OF THE BRAIN AND SPINAL CORD Part 1 By LESLIE G. KILOH, M.D., M.R.C.P., D.P.M. First Assistant in the Joint Department of Psychological Medicine, Royal Victoria Infirmary and University of Durham Introduction general circulatory efficiency at the time of the Little interest is shown at present in the syn- catastrophe is of the greatest importance. An dromes of the arteries of the brain and spinal cord, occlusion, producing little effect in the presence of and this perhaps is related to the tendency to a normal blood pressure, may cause widespread minimize the importance of cerebral localization. pathological changes if hypotension co-exists. Yet these syndromes are far from being fully A marked discrepancy has been noted between elucidated and understood. It must be admitted the effects of ligation and of spontaneous throm- that in many cases precise localization is often of bosis of an artery. The former seldom produces little more than academic interest and ill effects whilst the latter frequently determines provides Protected by copyright. nothing but a measure of personal satisfaction to infarction. This is probably due to the tendency the physician. But it is worth recalling that the of a spontaneous thrombus to extend along the detailed study of the distribution of the bronchi affected vessel, sealing its branches and blocking and of the pathological anatomy of congenital its collateral circulation, and to the fact that the abnormalities of the heart, was similarly neglected arterial disease is so often generalized. -

Part Ii – Neurological Disorders

Part ii – Neurological Disorders CHAPTER 14 MOVEMENT DISORDERS AND MOTOR NEURONE DISEASE Dr William P. Howlett 2012 Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Moshi, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania BRIC 2012 University of Bergen PO Box 7800 NO-5020 Bergen Norway NEUROLOGY IN AFRICA William Howlett Illustrations: Ellinor Moldeklev Hoff, Department of Photos and Drawings, UiB Cover: Tor Vegard Tobiassen Layout: Christian Bakke, Division of Communication, University of Bergen E JØM RKE IL T M 2 Printed by Bodoni, Bergen, Norway 4 9 1 9 6 Trykksak Copyright © 2012 William Howlett NEUROLOGY IN AFRICA is freely available to download at Bergen Open Research Archive (https://bora.uib.no) www.uib.no/cih/en/resources/neurology-in-africa ISBN 978-82-7453-085-0 Notice/Disclaimer This publication is intended to give accurate information with regard to the subject matter covered. However medical knowledge is constantly changing and information may alter. It is the responsibility of the practitioner to determine the best treatment for the patient and readers are therefore obliged to check and verify information contained within the book. This recommendation is most important with regard to drugs used, their dose, route and duration of administration, indications and contraindications and side effects. The author and the publisher waive any and all liability for damages, injury or death to persons or property incurred, directly or indirectly by this publication. CONTENTS MOVEMENT DISORDERS AND MOTOR NEURONE DISEASE 329 PARKINSON’S DISEASE (PD) � � � � � � � � � � � -

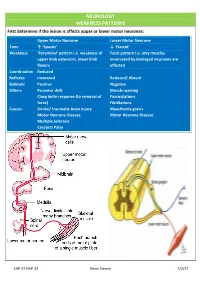

NEUROLOGY WEAKNESS PATTERNS First Determine If the Lesion Is Affects Upper Or Lower Motor Neurones

NEUROLOGY WEAKNESS PATTERNS First determine if the lesion is affects upper or lower motor neurones: Upper Motor Neurone Lower Motor Neurone Tone ↑ ‘Spastic’ ↓ ‘Flaccid’ Weakness ‘Pyramidal’ pattern i.e. weakness of Focal pattern i.e. only muscles upper limb extensors, lower limb innervated by damaged neurones are flexors affected Coordination Reduced Reflexes Increased Reduced/ Absent Babinski Positive Negative Others Pronator drift Muscle wasting Clasp knife response (to removal of Fasciculations force) Fibrillations Causes Stroke/ traumatic brain injury Myasthenia gravis Motor Neurone Disease Motor Neurone Disease Multiple Sclerosis Cerebral Palsy CAP 37 HAP 33 Kevin Gervin 7/2/17 What do we mean by extrapyramidal? Extrapyramidal symptoms Symptoms affecting tracts other than corticospinal and corticobulbar Extrapyramidal tracts don’t travel through the medullary pyramids The system regulates posture and muscle tone so pathology usually leads to movement disorders Most common cause is typical antipsychotics affecting Dopamine (D2) receptors e.g. haloperidol Treatment is anticholinergics e.g. procyclidine Extrapyramidal conditions: Acute dystonic reactions → muscle spasms e.g. neck, jaw, back. Akathisia- feeling of internal restlessness Drug induced Parkinsonism- tremor, rigidity etc. Tardive dyskinesia- involuntary muscle movements of lower face and extremities, often permanent What’s the difference between a Bulbar and Pseudobulbar palsy? Bulbar Pseudobulbar Pathophysiology LMN lesion CN V, VII, IX- XII Disease of corticobulbar -

Lewy Body Diseases and Multiple System Atrophy As ␣-Synucleinopathies

Molecular Psychiatry (1998) 3, 462–465 1998 Stockton Press All rights reserved 1359–4184/98 $12.00 GUEST EDITORIAL Lewy body diseases and multiple system atrophy as ␣-synucleinopathies Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies synuclein are the first known genetic causes of Parkin- are among the most common neurodegenerative dis- son’s disease. They are located in the amino-terminal eases. They share the Lewy body and the Lewy neurite half of ␣-synuclein, which consists of seven imperfect as their defining neuropathological characteristics. repeats of 11 amino acids each, with the consensus Originally described in 1912 as a light-microscopic sequence KTKEGV (Figure 1). It has been suggested entity, the Lewy body was shown to be made of abnor- that ␣-synuclein may bind through these repeats to mal filaments in the 1960s. Over the past year, the bio- membranes rich in acidic phospholipids.3 chemical nature of the Lewy body filament has been This work raised the question whether ␣-synuclein revealed. is a component of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites of A large number of different proteins has been idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and of dementia with reported to be present in Lewy bodies and Lewy neur- Lewy bodies. Using well-characterised anti-␣-synuc- ites by immunohistochemical methods. However, these lein antibodies, Spillantini et al showed strong staining findings do not permit us to distinguish between of both Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in idiopathic intrinsic Lewy body components and normal cellular Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies.4 constituents that get merely trapped in the filaments They also reported the lack of staining of these patho- that make up the Lewy body.