Note Deconstructing the Façade of Amateurism: Antitrust And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LSU Basketball Vs

THE BRADY ERA | In 10th YEAR, 6 POSTSEASON TOURN., 3 WESTERN DIV. and 2 SEC TITLES; 2006 FINAL 4 LSU Basketball vs. University of Connecticut January 6, 2007, 8 p.m. CST (LSU Sports Radio Network, ESPN) Pete Maravich Assembly Center -- Baton Rogue, La. LSU (10-3) Probable LSU Starters (based on the last game): G -- 2Dameon Mason (6-6, 183, Jr., Kansas City, Mo.) 8.0 ppg, 3.5 rpg, 1.2 apg NOVEMBER Mason started last four games, 11 in all this season ... Had 14, 13 and 11 points during the three games of the 9 E. A. Sports (Exh.) W, 70-65 HCF Classic ... 14 vs. Wright State (12/27) season est ... Out of starting lineup against Oregon State (12/17) 15 Louisiana College (Exh.) W, 94-41 and Washington (12/20) because of migraines ... Five total games scoring in double figures. 17 Nicholls State W, 96-42 19 Louisiana-Monroe (CST) W, 88-57 G -- 14 Garrett Temple (6-5, 190, So., Baton Rouge, La.) 10.2 ppg, 2.8 rpg, 4.1 apg 25 #24 Wichita State (CST) L, 53-57 Six games in double figures ... Had career highs of seven assists in back-to-back games of HCF Classic (Miss. 29 McNeese State (CST) W, 91-57 Valley, 12/28; Samford 12/29) with just five combined turnovers ... In first seven games had 23 assists and just DECEMBER 7 turnovers ... Career high of 18 at Tulane (12/2) with 17 vs. McNeese (11/29) and at Oregon State (12/17) ... 2 At Tulane (1) W, 74-67 Earned reputation as defensive stopper after holding Duke’s J.J. -

Bankruptcy Forms for Non-Individuals, Is Available

Case 16-50379 Doc 1 Filed 01/05/16 Entered 01/05/16 17:02:40 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 27 Fill in this information to identify your case: United States Bankruptcy Court for the: NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA Case number (if known) Chapter you are filing under: Chapter 7 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Check if this an amended filing Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy 12/15 If more space is needed, attach a separate sheet to this form. On the top of any additional pages, write the debtor's name and case number (if known). For more information, a separate document, Instructions for Bankruptcy Forms for Non-Individuals, is available. 1. Debtor's name Titan Team Management, LLC 2. All other names debtor used in the last 8 years Include any assumed names, trade names and doing business as names 3. Debtor's federal Employer Identification 45-3985275 Number (EIN) 4. Debtor's address Principal place of business Mailing address, if different from principal place of business 2150 Boggs Road, Suite 300/370 Duluth, GA 30096 Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code P.O. Box, Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code Gwinnett Location of principal assets, if different from principal County place of business Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code 5. Debtor's website (URL) titanteamsports.com 6. Type of debtor Corporation (including Limited Liability Company (LLC) and Limited Liability Partnership (LLP)) Partnership Other. Specify: Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy page 1 Case 16-50379 Doc 1 Filed 01/05/16 Entered 01/05/16 17:02:40 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 27 Debtor Titan Team Management, LLC Case number (if known) Name 7. -

Ellies 2018 Finalists Announced

Ellies 2018 Finalists Announced New York, The New Yorker top list of National Magazine Award nominees; CNN’s Don Lemon to host annual awards lunch on March 13 NEW YORK, NY (February 1, 2018)—The American Society of Magazine Editors today published the list of finalists for the 2018 National Magazine Awards for Print and Digital Media. For the fifth year, the finalists were first announced in a 90-minute Twittercast. ASME will celebrate the 53rd presentation of the Ellies when each of the 104 finalists is honored at the annual awards lunch. The 2018 winners will be announced during a lunchtime presentation on Tuesday, March 13, at Cipriani Wall Street in New York. The lunch will be hosted by Don Lemon, the anchor of “CNN Tonight With Don Lemon,” airing weeknights at 10. More than 500 magazine editors and publishers are expected to attend. The winners receive “Ellies,” the elephant-shaped statuettes that give the awards their name. The awards lunch will include the presentation of the Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame Award to the founding editor of Metropolitan Home and Saveur, Dorothy Kalins. Danny Meyer, the chief executive officer of the Union Square Hospitality Group and founder of Shake Shack, will present the Hall of Fame Award to Kalins on behalf of ASME. The 2018 ASME Award for Fiction will also be presented to Michael Ray, the editor of Zoetrope: All-Story. The winners of the 2018 ASME Next Awards for Journalists Under 30 will be honored as well. This year 57 media organizations were nominated in 20 categories, including two new categories, Social Media and Digital Innovation. -

ECF 56 Third Amended Complaint

Case 1:19-cv-00160-RMC Document 56 Filed 09/19/19 Page 1 of 27 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE .DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TAMRYN SPRUTLL and JACOB SUNDSTROM, individually and on behalf of all those similarly situated, Plaintiffs, Civil Action No.: l:l 9-cv-00160-RMC vs. Class Action Complaint VOX MEDIA, INC, Jury Trial Demanded Defendants. THIRD AMENDED COMPLAINT I. INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs Tainryn Spruill and Jacob Sundstrom (together, "Plaintiffs") bring this class and representative action against Defendant Vox Media, Inc., ("Defendant' or "Vox") on behalf of themselves and all other former and current paid content contributors for Vox's sports blogging network. and flagship property SB :Nation in California, who Vox classified as independent contractors. S.B Nation operates over 300 team. sites dedicated to publishing written articles, videos, and other content on professional and college sports. Each team. site posts daily coverage on games, statistics, player trades, and culture. 'The more traffic the team sites attract, the more advertising revenue Vox generates. Vox pays Plaintiffs and similarly situated class members ("Content Contributors") a small monthly stipend to create and edit the written, video, and. audio content on these team sites. Content Contributors' posts are the core of Vox's business. 2. .During the entire class period, Vox. uniformly and consistently misclassfied Content Contributors —including job titles such as Site Manager, Associate Editor, Managing Editor, Deputy Editor, and Contributor — as independent contractors in order to avoid its duties 1 764747.8 Case 1:19-cv-00160-RMC Document 56 Filed 09/19/19 Page 2 of 27 and obligations owed to employees under California law and to gain. -

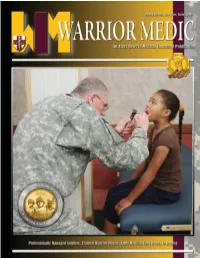

Table of Contents Words from the Wise

Table Of Contents Words from the Wise ....................................4-5 Expanding Readiness Capabilities ..................6 Company Affirms Support of Reserve..........7 Panama Residents Benefit from Army Reserve Medical Training................8 Reserve Surgeon Buried With Honors ..........9 Commentary: Community Events Unite Civilians, Soldiers ............................10 Historic Command Tenure Ends ..................11 Soldier Saves a Life..........................................12 Officer Receives Leadership Award..............12 74-year-old Set for Another Combat Tour..13 An Optical Milestone ......................................13 Healing Iraq ......................................................14 AR-MEDCOM Solder Helps Inaugurate New Commander-In-Chief......................15 'Paradise' is a Medical Nightmare for Some Locals ..................................16-17 Angels of the Battlefield ................................18 Unit Trains Iraqi Nurses ................................19 AR-MEDCOM NCO Feature Story: 369th CSH NCOs......................................20 'Combat Gynecologist' Returns ....................21 At 52, Dallas Cardiologist Answered Call to Serve................................................22 Soldiers Help Homeless Vets ........................23 Commentary: A MER Can Help ..................24 Yellow Ribbon Reintegration Program ........25 Bike Ride Unites Unit, Community ..............26 AR-MEDCOM Soldier New MALO ..........27 On The Cover: Lt. Col. Thomas Murphy, a physician serving with the -

How Cities Can Benefit from America's Fastest Growing Workforce Trend

COMMUNITIES AND THE GIG ECONOMY How cities can benefit from America’s fastest growing workforce trend BY PATRICK TUOHEY, LINDSEY ZEA OWEN PARKER AND SCOTT TUTTLE 4700 W. ROCHELLE AVE., SUITE 141, LAS VEGAS, NEVADA | (702) 546-8736 | BETTER-CITIES.ORG ANNUAL REPORT - 2019/20 M I S S I O N Better Cities Project uncovers ideas that work, promotes realistic solutions and forges partnerships that help people in America’s largest cities live free and happy lives. ANNUAL REPORT - 2019/20 BETTER CITIES PROJECT WHAT DOES A NEW CONTENTS WAY OF WORKING 2 MEAN FOR CITIES? INTRODUCTION he gig economy is big and growing — 4 THE STATE OF THE GIG even if there is not yet an agreed-upon ECONOMY T definition of the term. For cities, this offers the prospect of added tax revenue 5 and economic resilience. But often, legacy METHODOLOGY policies hold back gig workers. Given the organic growth in gig work and its function as a safety net 6 for millions of workers impacted by the pandemic, it’s reasonable to AMERICA’S GIG ECONOMY IS expect gig-work growth will continue and even speed up; cities with a IN A TUG OF WAR ACROSS THE NATION permissive regulatory structure may be more insulated from econom- ic chaos. Key areas for city leaders to focus on include: 7 WORKERS LIKE GIG WORK n THE GAP BETWEEN REGULATION AND TECHNOLOGY CAN HOLD CITI- ZENS BACK AND COST SIGNIFICANT TAX REVENUE. Regulation often lags behind technological innovation and, in the worst circumstanc- 9 es, can threaten to snuff it out. -

Tripadvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson As President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit

TripAdvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson as President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit October 25, 2018 A recognized leader in digital media, new CoreX president will oversee the TripAdvisor brand, lead content development and scale revenue generating consumer products and features that enhance the travel journey NEEDHAM, Mass., Oct. 25, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- TripAdvisor, the world's largest travel site*, today announced that Lindsay Nelson will join the company as president of TripAdvisor's Core Experience (CoreX) business unit, effective October 30, 2018. In this role, Nelson will oversee the global TripAdvisor platform and brand, helping the nearly half a billion customers that visit TripAdvisor monthly have a better and more inspired travel planning experience. "I'm really excited to have Lindsay join TripAdvisor as the president of Core Experience and welcome her to the TripAdvisor management team," said Stephen Kaufer, CEO and president, TripAdvisor, Inc. "Lindsay is an accomplished executive with an incredible track record of scaling media businesses without sacrificing the integrity of the content important to users, and her skill set will be invaluable as we continue to maintain and grow TripAdvisor's position as a global leader in travel." "When we created the CoreX business unit earlier this year, we were searching for a leader to be the guardian of the traveler's journey across all our offerings – accommodations, air, restaurants and experiences. After a thorough search, we are confident that Lindsay is the right executive with the experience and know-how to enhance the TripAdvisor brand as we evolve to become a more social and personalized offering for our community," added Kaufer. -

Cosida E-Digest August 2014 • 1 Cosida E-Digest August 2014 • 2 Cosida E-Digest August 2014 • 3 Cosida E-Digest August 2014 • 4 2014 Cosida AUGUST E-DIGEST

CoSIDA E-Digest August 2014 • 1 CoSIDA E-Digest August 2014 • 2 CoSIDA E-Digest August 2014 • 3 CoSIDA E-Digest August 2014 • 4 2014 CoSIDA AUGUST E-DIGEST Supporting CoSIDA > • ASAP Sports .......................................48 • Capital One ...........................................2 • CBS Sports Network/Stat Crew.........42 • College Football Playoff ....................42 • CoSIDA’s “Service Providers” ..........34 Table of Contents . • ESPN ...................................................12 2014-15 CoSIDA Board & Staff ........................................................................ 6-7 2014 CoSIDA Convention Photo Gallery ........................................................ 8-31 • Heisman Trophy .................................38 Capital One Academic All-America® • Learfield Sports ....................................4 Academic All-American of the Year Videos .............................................. 32-33 Jim Seavey Named Massassachusetts Maritime Employee of the Year ........... 35 • NCAA .....................................................3 Bob Vazquez Retires After 37 Years in Media Relations ................................... 36 • NewTek ..................................................4 Annual Membership and Convention Totals ...................................................... 37 Bill Morgal and Shawn Medeiros Honored by USTFCCCA ............................... 39 • NBA ......................................................42 LSU’s Will Stafford Honored by USTFCCCA .................................................... -

NEI Focus: City Creatives Economy Initiative, Round Two

20140203-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 1/31/2014 6:25 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 30, No. 5 FEBRUARY 3 – 9, 2014 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2014 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved Page 3 ROUND-TWO FUNDERS OF NEI Here are the 10 funders of the New Budget cuts put defense NEI focus: City creatives Economy Initiative, round two. Ⅲ The John S. and James L. Knight contracts in line of fire Foundation (Miami): $5 million “Entrepreneurship and innova- Ⅲ Ford Foundation (New York): $5 million 2nd funding round tion, as stand-alones, are valuable Ⅲ The Kresge Foundation (Detroit): in growing the economy,” said $5 million LARRY PEPLIN NEI Executive Director Dave Eg- Ⅲ W.K. Kellogg Foundation (Battle to target innovation, ner. “But the more we can con- Creek): $5 million nect them, the greater we can ac- Ⅲ The William Davidson Foundation celerate each. (Troy): $5 million entrepreneurism “In the end, without innova- Ⅲ Hudson-Webber Foundation tion, there are no new ideas to (Detroit): $2.5 million Amid financial emergency, BY SHERRI WELCH commercialize. And without en- Ⅲ Charles Stewart Mott Foundation CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS Egner trepreneurs at the ready, there’s (Flint): $2 million Highland Park’s hopeful no one to commercialize them.” Ⅲ Community Foundation for After seven years and nearly $100 million in invest- NEI’s initial funders and one new foundation have Southeast Michigan (Detroit): Calif. firm poised to buy ment, the New Economy Initiative has figured out the committed a second-round investment of $33 million $1.5 million types of projects that will give it the most bang for its toward a $40 million target, Egner told Crain’s last Ⅲ The Max M. -

Homosexuality and the Olympic Movement*

Homosexuality and the Olympic Movement* By Matthew Baniak and Ian Jobling Sport remains “one of the last bastions of cultural and the inception of the modern Games until today. An Matthew Baniak institutional homophobia” in Western societies, despite examination of key historical events that shaped the was an Exchange Student from the University of Saskatchewan, the advances made since the birth of the gay rights gay rights movement helps determine the effect homo- Canada at the University of movement.1 In a heteronormative culture such as sport, sexuality has had on the Olympic Movement. Through Queensland, Australia in 2013. Email address: mob802@mail. lack of knowledge and understanding has led to homo- such scrutiny, one may see that the Movement has usask.ca phobia and discrimination against openly gay athletes. changed since the inaugural modern Olympic Games The Olympic Games are no exception to this stigma. The in 1896. With the momentum of news surrounding the Ian Jobling goal of the Olympic Movement is to 2014 Sochi Games and the anti-gay laws in Russia, this is Director, Centre of Olympic … contribute to building a peaceful and better world issue of homosexuality and the Olympic Movement Studies and Honorary Associate by educating youth through sport united with art has never been so significant. Sections of this article Professor, School of Human Movement Studies, University of and culture practiced without discrimination of any will outline the effect homosexuality has had on the Queensland. Email address: kind and in the -

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

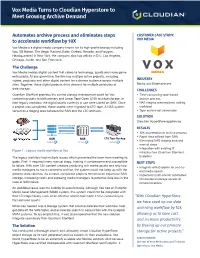

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

Case 16-44815 Doc 638 Filed 11/17/16 Entered 11/18/16 00:01:16 Imaged Certificate of Notice Pg 1 of 22

Case 16-44815 Doc 638 Filed 11/17/16 Entered 11/18/16 00:01:16 Imaged Certificate of Notice Pg 1 of 22 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MISSOURI EASTERN DIVISION In re: #464 Case No. 16-44815-705 THI SELLING CORPORATION, f/k/a Chapter 11 TOTAL HOCKEY, INC., et al.,1 (Jointly Administered) Debtors. ORDER (I) APPROVING PAYMENT OF ADMINISTRATIVE EXPENSES AND UNSECURED PRIORITY CLAIMS; (II) APPROVING PRO RATA DISTRIBUTIONS ON ACCOUNT OF GENERAL UNSECURED CLAIMS; (III) AUTHORIZING THE DESTRUCTION, ABANDONMENT, OR OTHER DISPOSITION OF REMAINING RECORDS AND DOCUMENTS; (IV) APPROVING DISMISSAL OF THE DEBTORS’ CHAPTER 11 CASES; AND (V) GRANTING RELATED RELIEF Upon the motion [Docket No. 464] (the “Motion”)2 of the Debtors for entry of an order, pursuant to 105(a), 305, 349, 363(b)(1), 554(a) and 1112(b) of title 11 of the United States Code (as amended, the “Bankruptcy Code”), and rules 1017, 2002 and 6007 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedures (the “Bankruptcy Rules”), for entry orders (i) approving payment of administrative expenses and unsecured priority claims; (ii) approving pro rata distributions on account of general unsecured claims; (iii) authorizing the destruction, abandonment or other disposition of remaining records and documents; (iii) dismissing the Debtors’ Chapter 11 Cases, and (v) granting related relief, as more fully set forth in the Motion; and the Court having jurisdiction to consider the Motion and the relief requested therein pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1334; and consideration of the Motion and the relief 1 The Debtors in these cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtors’ federal tax identification number, are: THI Selling Corporation (f/k/a Total Hockey, Inc.) (4010); PBC Selling Corporation (f/k/a Player’s Bench Corporation) (8085); and Hipcheck, L.L.C.