Threatened, Endangered, Candidate & Proposed Plant Species of Utah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USFWS) 2008A, 17 Pp.)

U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE SPECIES ASSESSMENT AND LISTING PRIORITY ASSIGNMENT FORM Scientific Name: Astragalus anserinus Common Name: Goose Creek milkvetch Lead region: Region 6 (Mountain-Prairie Region) Information current as of: 03/29/2013 Status/Action ___ Funding provided for a proposed rule. Assessment not updated. ___ Species Assessment - determined species did not meet the definition of the endangered or threatened under the Act and, therefore, was not elevated to the Candidate status. ___ New Candidate _X_ Continuing Candidate ___ Candidate Removal ___ Taxon is more abundant or widespread than previously believed or not subject to the degree of threats sufficient to warrant issuance of a proposed listing or continuance of candidate status ___ Taxon not subject to the degree of threats sufficient to warrant issuance of a proposed listing or continuance of candidate status due, in part or totally, to conservation efforts that remove or reduce the threats to the species ___ Range is no longer a U.S. territory ___ Insufficient information exists on biological vulnerability and threats to support listing ___ Taxon mistakenly included in past notice of review ___ Taxon does not meet the definition of "species" ___ Taxon believed to be extinct ___ Conservation efforts have removed or reduced threats ___ More abundant than believed, diminished threats, or threats eliminated. Petition Information ___ Non-Petitioned _X_ Petitioned - Date petition received: 02/03/2004 90-Day Positive:08/16/2007 12 Month Positive:09/10/2009 Did the Petition -

Field Release of the Leaf-Feeding Moth, Hypena Opulenta (Christoph)

United States Department of Field release of the leaf-feeding Agriculture moth, Hypena opulenta Marketing and Regulatory (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Programs Noctuidae), for classical Animal and Plant Health Inspection biological control of swallow- Service worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Field release of the leaf-feeding moth, Hypena opulenta (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), for classical biological control of swallow-worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. -

Project: 2003-NPS-305-P Seed Fates of Arctomecon Californica By

Project: 2003-NPS-305-P Seed Fates of Arctomecon californica By: Laura Megill & Dr. Lawrence Walker University of Nevada, Las Vegas Final Report Clark County Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan June 30, 2006 ** A copy of the finished thesis and subsequent publications will be sent upon completion. INTRODUCTION The Las Vegas bearpoppy, Arctomecon californica Torr. and Frem., is a rare herbaceous perennial endemic to the Mojave Desert that mainly inhabits gypsum outcrops. The Las Vegas bearpoppy is listed as Critically Endangered by the State of Nevada (Mistretta et al., 1995). A vital aspect of the life history of the bearpoppy that has been overlooked in previous studies is the fate of seeds. The unknown fate of the bearpoppy seeds provides an information gap in conservation management plans that is critical to plan mitigation measures (Powell and Walker 2003). Therefore, the objective of this research project is to determine the seed fates of the Las Vegas bearpoppy to further promote conservation efforts. The scope of this project follows seed fates through seed production, seed dispersal, and granivory to incorporation within the soil seed bank. In addition, seed viability testing will occur throughout the project to substantiate seed fate data. The research data will be collected from four study areas with an additional area added for soil seed bank studies traversing the natural range of the Las Vegas bearpoppy over a two-year consecutive period. The following hypotheses will be addressed in this research study: (1) Seed production corresponds to capsule size and number of rosettes. (2) Primary seed dispersal declines leptokurtically from the source. -

Milkweeds a Conservation Practitioner’S Guide

Milkweeds A Conservation Practitioner’s Guide Plant Ecology, Seed Production Methods, and Habitat Restoration Opportunities Brianna Borders and Eric Lee-Mäder The Xerces Society FOR INVERTEBRATE CONSERVATION The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation 1 MILKWEEDS A Conservation Practitioner's Guide Brianna Borders Eric Lee-Mäder The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation Oregon • California • Minnesota • Nebraska North Carolina • New Jersey • Texas www.xerces.org Protecting the Life that Sustains Us The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation is a nonproft organization that protects wildlife through the conservation of invertebrates and their habitat. Established in 1971, the Society is at the forefront of invertebrate protection, harnessing the knowledge of scientists and the enthusiasm of citizens to implement conservation programs worldwide. The Society uses advocacy, education, and applied research to promote invertebrate conservation. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation 628 NE Broadway, Suite 200, Portland, OR 97232 Tel (855) 232-6639 Fax (503) 233-6794 www.xerces.org Regional ofces in California, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Texas. The Xerces Society is an equal opportunity employer and provider. © 2014 by The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation Acknowledgements Funding for this report was provided by a national USDA-NRCS Conservation Innovation Grant, The Monarch Joint Venture, The Hind Foundation, SeaWorld & Busch Gardens Conservation Fund, Disney Worldwide Conservation Fund, The Elizabeth Ordway Dunn Foundation, The William H. and Mattie Wat- tis Harris Foundation, The CERES Foundation, Turner Foundation Inc., The McCune Charitable Founda- tion, and Xerces Society members. Thank you. For a full list of acknowledgements, including project partners and document reviewers, please see the Acknowledgements section on page 113. -

Asclepias Welshii N& P

TOC Page | 31 Asclepias welshii N& P. Holmgren Welsh’s Milkweed Family: Asclepiadaceae Synonyms: None NESL Status: G3 Federal Status: Listed Threatened (52 FR 41435 41441) Plant Description: Herbaceous perennial from extensive underground rootstock; stems erect, stout, 2.5 – 10 dm tall; leaves 6 – 9 (15) cam long, 3 – 6 (8) cam broad, opposite, elliptic to ovate or obovate, rounded to truncate and mucronate apically, rounded to cordate basally; young growth densely wooly, upper leaves with short petiole, lower leaves without petiole. Flowers cream-colored with a rose-tinged middle, 12 – 14 mm wide, in a tight spherical inflorescence, 7 cm wide, with ca. 30 flowers. Flowering occurs from June to July; seed development and dispersal occur from July to early September. The juvenile form of this species has long, linear leaves. Because of the differences between juvenile and mature plants, juveniles are easily overlooked or misidentified. Similar Species: Recognized by its large seeds (20+ mm long), spreading to pendulous follicles, cottony-pubescent pedicles, and the main leaves obovate to broadly elliptic, rounded to truncate apically. Habitat: Active sand dunes derived from Navajo sandstone in sagebrush, juniper, and ponderosa pine communities. Known populations occur from 5000 to 6230 ft elevation. General Distribution: Kane Co, UT, northern AZ. Navajo Nation Distribution: Coconino Co, north of Tuba City, south of Monument Valley in Navajo & Apache counties. Potential Navajo Nation Distribution: All active sand dunes between Page and Tuba City, east to the Chinle Creek drainage. Survey Period: June through September. Suitable habitat can be identified year round. Recommended Avoidance: A 200 ft buffer zone is recommended to avoid disturbance; maybe more or less, depending on size and nature of the project References: Arizona Rare Plant Committee. -

US Fish and Wildlife Service

BARNEBY REED-MUSTARD (S. barnebyi ) CLAY REED-MUSTARD SHRUBBY REED-MUSTARD (S,arguillacea) (S. suffrutescens) .-~ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service UTAH REED—MUSTARDS: CLAY REED-MUSTARD (SCHOENOCRAMBE ARGILLACEA) BARNEBY REED—MUSTARD (SCHOENOCRAMBE BARNEBYI) SI-IRUBBY REED-MUSTARD (SCHOENOCRAMBE SUFFRUTESCENS) RECOVERY PLAN Prepared by Region 6, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Approved: Date: (~19~- Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions which are believed to be required to recover and/or protect the species. Plans are prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, sometimes with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives will only be attained and funds expended contingent upon appropriations, priorities, and other budgetary constraints. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or approvals of any individuals or agencies, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, involved in the plan formulation. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as an~roved Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature Citation should read as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Utah reed—mustards: clay reed—mustard (Schoenocrambe argillacea), Barneby reed-mustard (Schoenocrambe barnebyl), shrubby reed—mustard (Schoenacranibe suffrutescens) recovery plan. Denver, Colorado. 22 pp. Additional copies may be purchased from: Fish and Wildlife Reference Service 5430 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 110 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 Telephone: 301/492—6403 or 1—800—582—3421 The fee for the plan varies depending on the number of pages of the plan. -

The Plant Press the ARIZONA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY

The Plant Press THE ARIZONA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY Volume 36, Number 1 Summer 2013 In this Issue: Plants of the Madrean Archipelago 1-4 Floras in the Madrean Archipelago Conference 5-8 Abstracts of Botanical Papers Presented in the Madrean Archipelago Conference Southwest Coralbean (Erythrina flabelliformis). Plus 11-19 Conservation Priority Floras in the Madrean Archipelago Setting for Arizona G1 Conference and G2 Plant Species: A Regional Assessment by Thomas R. Van Devender1. Photos courtesy the author. & Our Regular Features Today the term ‘bioblitz’ is popular, meaning an intensive effort in a short period to document the diversity of animals and plants in an area. The first bioblitz in the southwestern 2 President’s Note United States was the 1848-1855 survey of the new boundary between the United States and Mexico after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848 ended the Mexican-American War. 8 Who’s Who at AZNPS The border between El Paso, Texas and the Colorado River in Arizona was surveyed in 1855- 9 & 17 Book Reviews 1856, following the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. Besides surveying and marking the border with monuments, these were expeditions that made extensive animal and plant collections, 10 Spotlight on a Native often by U.S. Army physicians. Botanists John M. Bigelow (Charphochaete bigelovii), Charles Plant C. Parry (Agave parryi), Arthur C. V. Schott (Stephanomeria schotti), Edmund K. Smith (Rhamnus smithii), George Thurber (Stenocereus thurberi), and Charles Wright (Cheilanthes wrightii) made the first systematic plant collection in the Arizona-Sonora borderlands. ©2013 Arizona Native Plant In 1892-94, Edgar A. Mearns collected 30,000 animal and plant specimens on the second Society. -

Dynamics of a Dwarf Bear-Poppy (Arctomecon Humilis) Population Over a Sixteen-Year Period

Western North American Naturalist Volume 64 Number 4 Article 8 10-29-2004 Dynamics of a dwarf bear-poppy (Arctomecon humilis) population over a sixteen-year period K. T. Harper Brigham Young University Renée Van Buren Utah Valley State College, Orem, Utah Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Harper, K. T. and Van Buren, Renée (2004) "Dynamics of a dwarf bear-poppy (Arctomecon humilis) population over a sixteen-year period," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 64 : No. 4 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol64/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 64(4), © 2004, pp 482–491 DYNAMICS OF A DWARF BEAR-POPPY (ARCTOMECON HUMILIS) POPULATION OVER A SIXTEEN-YEAR PERIOD K.T. Harper1,2 and Renée Van Buren3 ABSTRACT.—A population of the dwarf bear-poppy (Arctomecon humilis Coville, Papaveraceae) at Red Bluff, Wash- ington County, Utah, was monitored twice annually between 1987 and 2002. This is a narrowly endemic, gypsophilous species that has been formally listed as endangered since 1979. During the 16 years of observation, density of this species has fluctuated between 3 and 1336 individuals on the 0.07-ha monitoring plot. Moderate to large recruitments of seedlings occurred in 1992, 1995, and 2001. Seedling recruitments from a large, long-lived seed bank are triggered by abundant precipitation during the February–April period. -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

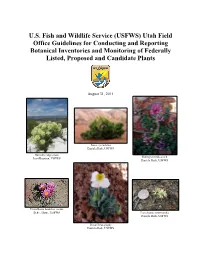

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Utah Field Office Guidelines for Conducting and Reporting Botanical Inventories and Monit

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Utah Field Office Guidelines for Conducting and Reporting Botanical Inventories and Monitoring of Federally Listed, Proposed and Candidate Plants August 31, 2011 Jones cycladenia Daniela Roth, USFWS Barneby ridge-cress Holmgren milk-vetch Jessi Brunson, USFWS Daniela Roth, USFWS Uinta Basin hookless cactus Bekee Hotze, USFWS Last chance townsendia Daniela Roth, USFWS Dwarf bear-poppy Daniela Roth, USFWS INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE These guidelines were developed by the USFWS Utah Field Office to clarify our office’s minimum standards for botanical surveys for sensitive (federally listed, proposed and candidate) plant species (collectively referred to throughout this document as “target species”). Although developed with considerable input from various partners (agency and non-governmental personnel), these guidelines are solely intended to represent the recommendations of the USFWS Utah Field Office and should not be assumed to satisfy the expectations of any other entity. These guidelines are intended to strengthen the quality of information used by the USFWS in assessing the status, trends, and vulnerability of target species to a wide array of factors and known threats. We also intend that these guidelines will be helpful to those who conduct and fund surveys by providing up-front guidance regarding our expectations for survey protocols and data reporting. These are intended as general guidelines establishing minimum criteria; the USFWS Utah Field Office reserves the right to establish additional standards on a case-by-case basis. Note: The Vernal Field Office of the BLM requires specific qualifications for conducing botanical field work in their jurisdiction; nothing in this document should be interpreted as replacing requirements in place by that (or any other) agency. -

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Daniel G. Milchunas General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-169 April 2006 Milchunas, Daniel G. 2006. Responses of plant communities to grazing in the southwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-169. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 126 p. Abstract Grazing by wild and domestic mammals can have small to large effects on plant communities, depend- ing on characteristics of the particular community and of the type and intensity of grazing. The broad objective of this report was to extensively review literature on the effects of grazing on 25 plant commu- nities of the southwestern U.S. in terms of plant species composition, aboveground primary productiv- ity, and root and soil attributes. Livestock grazing management and grazing systems are assessed, as are effects of small and large native mammals and feral species, when data are available. Emphasis is placed on the evolutionary history of grazing and productivity of the particular communities as deter- minants of response. After reviewing available studies for each community type, we compare changes in species composition with grazing among community types. Comparisons are also made between southwestern communities with a relatively short history of grazing and communities of the adjacent Great Plains with a long evolutionary history of grazing. Evidence for grazing as a factor in shifts from grasslands to shrublands is considered. An appendix outlines a new community classification system, which is followed in describing grazing impacts in prior sections. -

Morphological Variability and Genetic Diversity in Carex Buxbaumii and Carex Hartmaniorum (Cyperaceae) Populations

Morphological variability and genetic diversity in Carex buxbaumii and Carex hartmaniorum (Cyperaceae) populations Helena Wi¦cªaw1, Magdalena Szenejko1,2, Thea Kull3, Zofia Sotek1, Ewa R¦bacz-Maron4 and Jacob Koopman5 1 Institute of Marine and Environmental Sciences, University of Szczecin, Szczecin, Poland 2 Molecular Biology and Biotechnology Center, University of Szczecin, Szczecin, Poland 3 Institute of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Tartu, Estonia 4 Institute of Biology, University of Szczecin, Szczecin, Poland 5 Unaffiliated, Choszczno, Poland ABSTRACT Background. Carex buxbaumii and C. hartmaniorum are sister species of the clade Papilliferae within the monophyletic section Racemosae. An unambiguous identifica- tion of these species is relatively difficult due to the interspecific continuum of some morphological characters as well as the intraspecific variability. The study was aimed at determining the range of variability, both morphological and genetic, within and between these two closely related and similar species. Methods. The sedges were collected during botanical expeditions to Armenia, Estonia, the Netherlands, and Poland. The morphological separation of the two species and their populations was tested using the Discriminant Function Analysis (DFA). The genetic variability of the 19 Carex populations was assessed in the presence of eight Inter Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR) primers. Results. Results of the study indicate a considerable genetic affinity between the two sedge species (mean Si D 0.619). However, the populations of C. hartmaniorum are, morphologically and genetically, more homogenous than the populations of C. buxbaumii. Compared to C. hartmaniorum, C. buxbaumii usually has wider leaf Submitted 10 September 2020 blades, a shorter inflorescence, a lower number of spikes which are shorter, but wider, Accepted 7 April 2021 and longer bracts and utricles.