Intermittent Reduction in Ocean Heat Transport Into the Getz Ice Shelf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ekman Layer at the Sea Surface • Ekman Mass Transport • Application of Ekman Theory • Langmuir Circulation • Important Concepts

Principle of Oceanography Gholamreza Mashayekhinia 2013_2014 Response of the Upper Ocean to Winds Contents • Inertial Motion • Ekman Layer at the Sea Surface • Ekman Mass Transport • Application of Ekman Theory • Langmuir Circulation • Important Concepts Inertial Motion The response of the ocean to an impulse that sets the water in motion. For example, the impulse can be a strong wind blowing for a few hours. The water then moves under the influence of coriolis force and gravity. No other forces act on the water. In physics, the Coriolis effect is a deflection of moving objects when they are viewed in a rotating reference frame. This low pressure system over Iceland spins counter-clockwise due to balance between the Coriolis force and the pressure gradient force. Such motion is said to be inertial. The mass of water continues to move due to its inertia. If the water were in space, it would move in a straight line according to Newton's second law. But on a rotating Earth, the motion is much different. The equations of motion for a frictionless ocean are: 푑푢 1 휕푝 = − + 2Ω푣 푠푖푛휑 (1a) 푑푡 휌 휕푥 푑푣 1 휕푝 = − − 2Ω푢 푠푖푛휑 (1b) 푑푡 휌 휕푦 푑휔 1 휕푝 = − + 2Ω푢 푐표푠휑 − 푔 (1c) 푑푡 휌 휕푥 Where p is pressure, Ω = 2 π/(sidereal day) = 7.292 × 10-5 rad/s is the rotation of the Earth in fixed coordinates, and φ is latitude. We have also used Fi = 0 because the fluid is frictionless. Let's now look for simple solutions to these equations. To do this we must simplify the momentum equations. -

Article Is Available On- J.: the International Bathymetric Chart of the Southern Ocean Line At

The Cryosphere, 14, 1399–1408, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-14-1399-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Getz Ice Shelf melt enhanced by freshwater discharge from beneath the West Antarctic Ice Sheet Wei Wei1, Donald D. Blankenship1, Jamin S. Greenbaum1, Noel Gourmelen2, Christine F. Dow3, Thomas G. Richter1, Chad A. Greene4, Duncan A. Young1, SangHoon Lee5, Tae-Wan Kim5, Won Sang Lee5, and Karen M. Assmann6,a 1Institute for Geophysics and Department of Geological Sciences, Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA 2School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK 3Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada 4Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, USA 5Korea Polar Research Institute, Incheon, South Korea 6Department of Earth Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden apresent address: Institute of Marine Research, Tromsø, Norway Correspondence: Wei Wei ([email protected]) Received: 18 July 2019 – Discussion started: 26 July 2019 Revised: 8 March 2020 – Accepted: 10 March 2020 – Published: 27 April 2020 Abstract. Antarctica’s Getz Ice Shelf has been rapidly thin- 1 Introduction ning in recent years, producing more meltwater than any other ice shelf in the world. The influx of fresh water is The Getz Ice Shelf (Getz herein) in West Antarctica is over known to substantially influence ocean circulation and bi- 500 km long and 30 to 100 km wide; it produces more fresh ological productivity, but relatively little is known about water than any other source in Antarctica (Rignot et al., 2013; the factors controlling basal melt rate or how basal melt is Jacobs et al., 2013), and in recent years its melt rate has spatially distributed beneath the ice shelf. -

Glacier Change Along West Antarctica's Marie Byrd Land Sector

Glacier change along West Antarctica’s Marie Byrd Land Sector and links to inter-decadal atmosphere-ocean variability Frazer D.W. Christie1, Robert G. Bingham1, Noel Gourmelen1, Eric J. Steig2, Rosie R. Bisset1, Hamish D. Pritchard3, Kate Snow1 and Simon F.B. Tett1 5 1School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK 2Department of Earth & Space Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, USA 3British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge, UK Correspondence to: Frazer D.W. Christie ([email protected]) Abstract. Over the past 20 years satellite remote sensing has captured significant downwasting of glaciers that drain the West 10 Antarctic Ice Sheet into the ocean, particularly across the Amundsen Sea Sector. Along the neighbouring Marie Byrd Land Sector, situated west of Thwaites Glacier to Ross Ice Shelf, glaciological change has been only sparsely monitored. Here, we use optical satellite imagery to track grounding-line migration along the Marie Byrd Land Sector between 2003 and 2015, and compare observed changes with ICESat and CryoSat-2-derived surface elevation and thickness change records. During the observational period, 33% of the grounding line underwent retreat, with no significant advance recorded over the remainder 15 of the ~2200 km long coastline. The greatest retreat rates were observed along the 650-km-long Getz Ice Shelf, further west of which only minor retreat occurred. The relative glaciological stability west of Getz Ice Shelf can be attributed to a divergence of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current from the continental-shelf break at 135° W, coincident with a transition in the morphology of the continental shelf. Along Getz Ice Shelf, grounding-line retreat reduced by 68% during the CryoSat-2 era relative to earlier observations. -

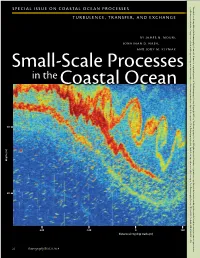

Small-Scale Processes in the Coastal Ocean

or collective redistirbution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The Oceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] ofor Th e The to: [email protected] Oceanography approval Oceanography correspondence PO all portionthe Send Society. ofwith any permitted articleonly photocopy by Society, is of machine, reposting, this means or collective or other redistirbution article has This been published in SPECIAL ISSUE ON CoasTal Ocean PRocesses TuRBulence, TRansFER, anD EXCHanGE Oceanography BY JAMes N. MouM, JonaTHan D. NasH, , Volume 21, Number 4, a quarterly journal of The Oceanography Society. Copyright 2008 by The Oceanography Society. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to copy this article for use in teaching and research. research. for this and teaching article copy to use in reserved.by The 2008 rights is granted journal ofCopyright OceanographyAll The Permission 21, NumberOceanography 4, a quarterly Society. Society. , Volume anD JODY M. KLYMak Small-Scale Processes in the Coastal Ocean 20 depth (m) 40 B ox 1931, ox R ockville, R epublication, systemmatic reproduction, reproduction, systemmatic epublication, MD 20849-1931, USA. -200 -100 0 100 distance along ship track (m) 22 Oceanography Vol.21, No.4 ABSTRACT. Varied observations over Oregon’s continental shelf illustrate the beauty and complexity of geophysical flows in coastal waters. Rapid, creative, and sometimes fortuitous sampling from ships and moorings has allowed detailed looks at boundary layer processes, internal waves (some extremely nonlinear), and coastal currents, including how they interact. These processes drive turbulence and mixing in shallow coastal waters and encourage rapid biological responses, yet are poorly understood and parameterized. -

On the Patterns of Wind-Power Input to the Ocean Circulation

2328 JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY VOLUME 41 On the Patterns of Wind-Power Input to the Ocean Circulation FABIEN ROQUET AND CARL WUNSCH Department of Earth, Atmosphere and Planetary Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts GURVAN MADEC Laboratoire d’Oce´anographie Dynamique et de Climatologie, Paris, France (Manuscript received 1 February 2011, in final form 12 July 2011) ABSTRACT Pathways of wind-power input into the ocean general circulation are analyzed using Ekman theory. Direct rates of wind work can be calculated through the wind stress acting on the surface geostrophic flow. However, because that energy is transported laterally in the Ekman layer, the injection into the geostrophic interior is actually controlled by Ekman pumping, with a pattern determined by the wind curl rather than the wind itself. Regions of power injection into the geostrophic interior are thus generally shifted poleward compared to regions of direct wind-power input, most notably in the Southern Ocean, where on average energy enters the interior 108 south of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current core. An interpretation of the wind-power input to the interior is proposed, expressed as a downward flux of pressure work. This energy flux is a measure of the work done by the Ekman pumping against the surface elevation pressure, helping to maintain the observed anomaly of sea surface height relative to the global-mean sea level. 1. Introduction or the input to surface gravity waves (601 TW; Wang and Huang 2004b), but they are not directly related to The wind stress, along with the secondary input from the interior flow. -

A Submarine Wall Protecting the Amundsen Sea Intensifies Melting of Neighboring Ice Shelves Özgür Gürses1, Vanessa Kolatschek1, Qiang Wang1, Christian B

The Cryosphere Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2019-32 Manuscript under review for journal The Cryosphere Discussion started: 15 March 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Brief communication: A submarine wall protecting the Amundsen Sea intensifies melting of neighboring ice shelves Özgür Gürses1, Vanessa Kolatschek1, Qiang Wang1, Christian B. Rodehacke1, 2 1Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, Bremerhaven, D-27570, Germany 5 2Danish Meteorological Institute, Copenhagen Ø, DK-2100, Denmark Correspondence to: Christian B. Rodehacke ([email protected]) Abstract Disintegration of ice shelves in the Amundsen Sea has the potential to cause sea level rise by inducing an acceleration of grounded ice streams. Moore et al (2018) proposed that using a submarine wall to block the penetration of warm water into 10 the ice shelf cavities could reduce this risk. We use a global sea ice-ocean model to show that a wall shielding the Amundsen Sea below 350 m depth successfully suppresses the inflow of warm water and reduces ice shelf melting. However, the warm water gets redirected towards neighboring ice shelves, which reduces the effectiveness of the wall. 1 Introduction One of the consequences of the warming in the Earth's climate system is sea level rise. Sea level rise will impact coastal 15 societies, and economic activities in these areas. Currently the main contributors to rising global mean sea level are a steric component driven by the thermal expansion of the warming ocean, the mass loss from the Greenland Ice Sheet, and the world-wide retreat of glaciers (Rietbroek et al., 2016). -

I!Ij 1)11 U.S

u... I C) C) co 1 USGS 0.. science for a changing world co :::2: Prepared in cooperation with the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom Coastal-change and glaciological map of the (I) ::E Bakutis Coast area, Antarctica: 1972-2002 ;::+' ::::r ::J c:r OJ ::J By Charles Swithinbank, RichardS. Williams, Jr. , Jane G. Ferrigno, OJ"" ::J 0.. Kevin M. Foley, and Christine E. Rosanova a :;:,..... CD ~ (I) I ("') a Geologic Investigations Series Map I- 2600- F (2d ed.) OJ ~ OJ '!; :;:, OJ ::J <0 co OJ ::J a_ <0 OJ n c; · a <0 n OJ 3 OJ "'C S, ..... :;:, CD a:r OJ ""a. (I) ("') a OJ .....(I) OJ <n OJ n OJ co .....,...... ~ C) .....,0 ~ b 0 C) b C) C) T....., Landsat Multispectral Scanner (MSS) image of Ma rtin and Bea r Peninsulas and Dotson Ice Shelf, Bakutis Coast, CT> C) An tarctica. Path 6, Row 11 3, acquired 30 December 1972. ? "T1 'N 0.. co 0.. 2003 ISBN 0-607-94827-2 U.S. Department of the Interior 0 Printed on rec ycl ed paper U.S. Geological Survey 9 11~ !1~~~,11~1!1! I!IJ 1)11 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I-2600-F (2d ed.) U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY COASTAL-CHANGE AND GLACIOLOGICAL MAP OF THE BAKUTIS COAST AREA, ANTARCTICA: 1972-2002 . By Charles Swithinbank, 1 RichardS. Williams, Jr.,2 Jane G. Ferrigno,3 Kevin M. Foley, 3 and Christine E. Rosanova4 INTRODUCTION areas Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+)), RADARSAT images, and other data where available, to compare Background changes over a 20- to 25- or 30-year time interval (or longer Changes in the area and volume of polar ice sheets are intri where data were available, as in the Antarctic Peninsula). -

Sea-Ice Melt Driven by Ice-Ocean Stresses on the Mesoscale

manuscript submitted to JGR: Oceans 1 Sea-ice melt driven by ice-ocean stresses on the 2 mesoscale 1 1 2 1 3 Mukund Gupta , John Marshall , Hajoon Song , Jean-Michel Campin , 1 4 Gianluca Meneghello 1 5 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2 6 Yonsei University 7 Key Points: 8 • Ice-ocean drag on the mesoscale generates Ekman pumping that brings warm wa- 9 ters up to the surface 10 • This melts sea-ice in winter and spring and reduces its mean thickness by 10 % 11 under compact ice regions 12 • Sea-ice formation (melt) in cyclones (anticyclones) produces deeper (shallower) 13 mixed layer depths. Corresponding author: Mukund Gupta, [email protected] {1{ manuscript submitted to JGR: Oceans 14 Abstract 15 The seasonal ice zone around both the Arctic and the Antarctic coasts is typically 16 characterized by warm and salty waters underlying a cold and fresh layer that insulates 17 sea-ice floating at the surface from vertical heat fluxes. Here we explore how a mesoscale 18 eddy field rubbing against ice at the surface can, through Ekman-induced vertical mo- 19 tion, bring warm waters up to the surface and partially melt the ice. We dub this the 20 `Eddy Ice Pumping' mechanism (EIP). When sea-ice is relatively motionless, underly- 21 ing mesoscale eddies experience a surface drag that generates Ekman upwelling in an- 22 ticyclones and downwelling in cyclones. An eddy composite analysis of a Southern Ocean 23 eddying channel model, capturing the interaction of the mesoscale with sea-ice, shows 24 that within the compact ice zone, the mixed layer depth in cyclones is very deep (∼ 500 25 m) due to brine rejection, and very shallow in anticyclones (∼ 20 m) due to sea-ice melt. -

Effects of the Earth's Rotation

Effects of the Earth’s Rotation C. Chen General Physical Oceanography MAR 555 School for Marine Sciences and Technology Umass-Dartmouth 1 One of the most important physical processes controlling the temporal and spatial variations of biological variables (nutrients, phytoplankton, zooplankton, etc) is the oceanic circulation. Since the circulation exists on the earth, it must be affected by the earth’s rotation. Question: How is the oceanic circulation affected by the earth’s rotation? The Coriolis force! Question: What is the Coriolis force? How is it defined? What is the difference between centrifugal and Coriolis forces? 2 Definition: • The Coriolis force is an apparent force that occurs when the fluid moves on a rotating frame. • The centrifugal force is an apparent force when an object is on a rotation frame. Based on these definitions, we learn that • The centrifugal force can occur when an object is at rest on a rotating frame; •The Coriolis force occurs only when an object is moving relative to the rotating frame. 3 Centrifugal Force Consider a ball of mass m attached to a string spinning around a circle of radius r at a constant angular velocity ω. r ω ω Conditions: 1) The speed of the ball is constant, but its direction is continuously changing; 2) The string acts like a force to pull the ball toward the axis of rotation. 4 Let us assume that the velocity of the ball: V at t V + !V " V = !V V + !V at t + !t ! V = V!" ! V !" d V d" d" r = V , limit !t # 0, = V = V ($ ) !t !t dt dt dt r !V "! V d" V = % r, and = %, dt V Therefore, d V "! = $& 2r dt ω r To keep the ball on the circle track, there must exist an additional force, which has the same magnitude as the centripetal acceleration but in an opposite direction. -

Your Cruise the Ross

The Ross Sea From 16/2/2022 From Ushuaia Ship: LE COMMANDANT CHARCOT to 12/3/2022 to Ushuaia Sailing the Ross Sea means discovering one of the most extreme and conserved universes in the Antarctic. Partially occupied by the Ross Ice Shelf, the largest ice platform in Antarctica , this immense bay located several hundred kilometres from theSouth Pole, is considered as the“ last ocean”, the last intact marine ecosystem and the largest marine sanctuary since 2016. Here, the cold is more intense, the wind more powerful, the ice more impressive, and the scenery more spectacular… In the heart of this polar Garden of Eden, where the ice shelf turns into icebergs, you will encounter prodigious fauna, as well assurrealist landscapes, with infinite shades of blue and stunning reliefs. Antarctic petrels, Minke whales, orcas and seals are at home here, as are very large Overnight in Santiago + flight Santiago/Ushuaia + transfers + flight Ushuaia/Santiago colonies of Adelie and emperor penguins. We are privileged guests in these extreme lands where we are at the mercy of weather and ice conditions. Our navigation will be determined by the type of ice we come across; as the coastal ice must be preserved, we will take this factor into account from day to day in our itineraries. The sailing schedule and any landings, activities and wildlife encounters are subject to weather and ice conditions. These experiences are unique and vary with each departure. The Captain and the Expedition Leader will make every effort to ensure that your experience is as rich as possible, while respecting safety instructions and regulations imposed by the IAATO. -

Ekman Transport in Balanced Currents with Curvature

MAY 2017 W E N E G R A T A N D T H O M A S 1189 Ekman Transport in Balanced Currents with Curvature JACOB O. WENEGRAT AND LEIF N. THOMAS Department of Earth System Science, Stanford University, Stanford, California (Manuscript received 24 October 2016, in final form 6 March 2017) ABSTRACT Ekman transport, the horizontal mass transport associated with a wind stress applied on the ocean surface, is modified by the vorticity of ocean currents, leading to what has been termed the nonlinear Ekman transport. This article extends earlier work on this topic by deriving solutions for the nonlinear Ekman transport valid in currents with curvature, such as a meandering jet or circular vortex, and for flows with the Rossby number approaching unity. Tilting of the horizontal vorticity of the Ekman flow by the balanced currents modifies the ocean response to surface forcing, such that, to leading order, winds parallel to the flow drive an Ekman transport that depends only on the shear vorticity component of the vertical relative vorticity, whereas across- flow winds drive transport dependent on the curvature vorticity. Curvature in the balanced flow field thus leads to an Ekman transport that differs from previous formulations derived under the assumption of straight flows. Notably, the theory also predicts a component of the transport aligned with the surface wind stress, contrary to classic Ekman theory. In the case of the circular vortex, the solutions given here can be used to calculate the vertical velocity to a higher order of accuracy than previous solutions, extending possible ap- plications of the theory to strong balanced flows. -

Getz Ice Shelf Melt Enhanced by Freshwater Discharge from Beneath the West Antarctic Ice Sheet

Edinburgh Research Explorer Getz Ice Shelf melt enhanced by freshwater discharge from beneath the West Antarctic Ice Sheet Citation for published version: Wei, W, Blankenship, DD, Greenbaum, JS, Gourmelen, N, Dow, CF, Richter, TG, Greene, CA, Young, DA, Lee, S, Kim, T, Lee, WS & Assmann, KM 2020, 'Getz Ice Shelf melt enhanced by freshwater discharge from beneath the West Antarctic Ice Sheet', Cryosphere, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 1399-1408. https://doi.org/10.5194/tc- 14-1399-2020 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.5194/tc-14-1399-2020 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Cryosphere Publisher Rights Statement: © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 The Cryosphere, 14, 1399–1408, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-14-1399-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.