Sea-Ice Melt Driven by Ice-Ocean Stresses on the Mesoscale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ekman Layer at the Sea Surface • Ekman Mass Transport • Application of Ekman Theory • Langmuir Circulation • Important Concepts

Principle of Oceanography Gholamreza Mashayekhinia 2013_2014 Response of the Upper Ocean to Winds Contents • Inertial Motion • Ekman Layer at the Sea Surface • Ekman Mass Transport • Application of Ekman Theory • Langmuir Circulation • Important Concepts Inertial Motion The response of the ocean to an impulse that sets the water in motion. For example, the impulse can be a strong wind blowing for a few hours. The water then moves under the influence of coriolis force and gravity. No other forces act on the water. In physics, the Coriolis effect is a deflection of moving objects when they are viewed in a rotating reference frame. This low pressure system over Iceland spins counter-clockwise due to balance between the Coriolis force and the pressure gradient force. Such motion is said to be inertial. The mass of water continues to move due to its inertia. If the water were in space, it would move in a straight line according to Newton's second law. But on a rotating Earth, the motion is much different. The equations of motion for a frictionless ocean are: 푑푢 1 휕푝 = − + 2Ω푣 푠푖푛휑 (1a) 푑푡 휌 휕푥 푑푣 1 휕푝 = − − 2Ω푢 푠푖푛휑 (1b) 푑푡 휌 휕푦 푑휔 1 휕푝 = − + 2Ω푢 푐표푠휑 − 푔 (1c) 푑푡 휌 휕푥 Where p is pressure, Ω = 2 π/(sidereal day) = 7.292 × 10-5 rad/s is the rotation of the Earth in fixed coordinates, and φ is latitude. We have also used Fi = 0 because the fluid is frictionless. Let's now look for simple solutions to these equations. To do this we must simplify the momentum equations. -

Small-Scale Processes in the Coastal Ocean

or collective redistirbution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The Oceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] ofor Th e The to: [email protected] Oceanography approval Oceanography correspondence PO all portionthe Send Society. ofwith any permitted articleonly photocopy by Society, is of machine, reposting, this means or collective or other redistirbution article has This been published in SPECIAL ISSUE ON CoasTal Ocean PRocesses TuRBulence, TRansFER, anD EXCHanGE Oceanography BY JAMes N. MouM, JonaTHan D. NasH, , Volume 21, Number 4, a quarterly journal of The Oceanography Society. Copyright 2008 by The Oceanography Society. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to copy this article for use in teaching and research. research. for this and teaching article copy to use in reserved.by The 2008 rights is granted journal ofCopyright OceanographyAll The Permission 21, NumberOceanography 4, a quarterly Society. Society. , Volume anD JODY M. KLYMak Small-Scale Processes in the Coastal Ocean 20 depth (m) 40 B ox 1931, ox R ockville, R epublication, systemmatic reproduction, reproduction, systemmatic epublication, MD 20849-1931, USA. -200 -100 0 100 distance along ship track (m) 22 Oceanography Vol.21, No.4 ABSTRACT. Varied observations over Oregon’s continental shelf illustrate the beauty and complexity of geophysical flows in coastal waters. Rapid, creative, and sometimes fortuitous sampling from ships and moorings has allowed detailed looks at boundary layer processes, internal waves (some extremely nonlinear), and coastal currents, including how they interact. These processes drive turbulence and mixing in shallow coastal waters and encourage rapid biological responses, yet are poorly understood and parameterized. -

On the Patterns of Wind-Power Input to the Ocean Circulation

2328 JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY VOLUME 41 On the Patterns of Wind-Power Input to the Ocean Circulation FABIEN ROQUET AND CARL WUNSCH Department of Earth, Atmosphere and Planetary Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts GURVAN MADEC Laboratoire d’Oce´anographie Dynamique et de Climatologie, Paris, France (Manuscript received 1 February 2011, in final form 12 July 2011) ABSTRACT Pathways of wind-power input into the ocean general circulation are analyzed using Ekman theory. Direct rates of wind work can be calculated through the wind stress acting on the surface geostrophic flow. However, because that energy is transported laterally in the Ekman layer, the injection into the geostrophic interior is actually controlled by Ekman pumping, with a pattern determined by the wind curl rather than the wind itself. Regions of power injection into the geostrophic interior are thus generally shifted poleward compared to regions of direct wind-power input, most notably in the Southern Ocean, where on average energy enters the interior 108 south of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current core. An interpretation of the wind-power input to the interior is proposed, expressed as a downward flux of pressure work. This energy flux is a measure of the work done by the Ekman pumping against the surface elevation pressure, helping to maintain the observed anomaly of sea surface height relative to the global-mean sea level. 1. Introduction or the input to surface gravity waves (601 TW; Wang and Huang 2004b), but they are not directly related to The wind stress, along with the secondary input from the interior flow. -

Effects of the Earth's Rotation

Effects of the Earth’s Rotation C. Chen General Physical Oceanography MAR 555 School for Marine Sciences and Technology Umass-Dartmouth 1 One of the most important physical processes controlling the temporal and spatial variations of biological variables (nutrients, phytoplankton, zooplankton, etc) is the oceanic circulation. Since the circulation exists on the earth, it must be affected by the earth’s rotation. Question: How is the oceanic circulation affected by the earth’s rotation? The Coriolis force! Question: What is the Coriolis force? How is it defined? What is the difference between centrifugal and Coriolis forces? 2 Definition: • The Coriolis force is an apparent force that occurs when the fluid moves on a rotating frame. • The centrifugal force is an apparent force when an object is on a rotation frame. Based on these definitions, we learn that • The centrifugal force can occur when an object is at rest on a rotating frame; •The Coriolis force occurs only when an object is moving relative to the rotating frame. 3 Centrifugal Force Consider a ball of mass m attached to a string spinning around a circle of radius r at a constant angular velocity ω. r ω ω Conditions: 1) The speed of the ball is constant, but its direction is continuously changing; 2) The string acts like a force to pull the ball toward the axis of rotation. 4 Let us assume that the velocity of the ball: V at t V + !V " V = !V V + !V at t + !t ! V = V!" ! V !" d V d" d" r = V , limit !t # 0, = V = V ($ ) !t !t dt dt dt r !V "! V d" V = % r, and = %, dt V Therefore, d V "! = $& 2r dt ω r To keep the ball on the circle track, there must exist an additional force, which has the same magnitude as the centripetal acceleration but in an opposite direction. -

Ekman Transport in Balanced Currents with Curvature

MAY 2017 W E N E G R A T A N D T H O M A S 1189 Ekman Transport in Balanced Currents with Curvature JACOB O. WENEGRAT AND LEIF N. THOMAS Department of Earth System Science, Stanford University, Stanford, California (Manuscript received 24 October 2016, in final form 6 March 2017) ABSTRACT Ekman transport, the horizontal mass transport associated with a wind stress applied on the ocean surface, is modified by the vorticity of ocean currents, leading to what has been termed the nonlinear Ekman transport. This article extends earlier work on this topic by deriving solutions for the nonlinear Ekman transport valid in currents with curvature, such as a meandering jet or circular vortex, and for flows with the Rossby number approaching unity. Tilting of the horizontal vorticity of the Ekman flow by the balanced currents modifies the ocean response to surface forcing, such that, to leading order, winds parallel to the flow drive an Ekman transport that depends only on the shear vorticity component of the vertical relative vorticity, whereas across- flow winds drive transport dependent on the curvature vorticity. Curvature in the balanced flow field thus leads to an Ekman transport that differs from previous formulations derived under the assumption of straight flows. Notably, the theory also predicts a component of the transport aligned with the surface wind stress, contrary to classic Ekman theory. In the case of the circular vortex, the solutions given here can be used to calculate the vertical velocity to a higher order of accuracy than previous solutions, extending possible ap- plications of the theory to strong balanced flows. -

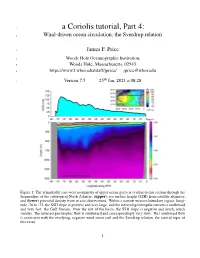

A Coriolis Tutorial, Part 4

1 a Coriolis tutorial, Part 4: 2 Wind-driven ocean circulation; the Sverdrup relation 3 James F. Price 4 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 5 Woods Hole, Massachusetts, 02543 6 https://www2.whoi.edu/staff/jprice/ [email protected] th 7 Version7.5 25 Jan, 2021 at 08:28 Figure 1: The remarkable east-west asymmetry of upper ocean gyres is evident in this section through the thermocline of the subtropical North Atlantic: (upper), sea surface height (SSH) from satellite altimetry, and (lower) potential density from in situ observations. Within a narrow western boundary region, longi- tude -76 to -72, the SSH slope is positive and very large, and the inferred geostrophic current is northward and very fast: the Gulf Stream. Over the rest of the basin, the SSH slope is negative and much, much smaller. The inferred geostrophic flow is southward and correspondingly very slow. This southward flow is consistent with the overlying, negative wind stress curl and the Sverdrup relation, the central topic of this essay. 1 8 Abstract. This essay is the fourth of a four part introduction to Earth’s rotation and the fluid dynamics 9 of the atmosphere and ocean. The theme is wind-driven ocean circulation, and the motive is to develop 10 insight for several major features of the observed ocean circulation, viz. western intensification of upper 11 ocean gyres and the geography of the mean and the seasonal variability. 12 A key element of this insight is an understanding of the Sverdrup relation between wind stress curl 13 and meridional transport. To that end, shallow water models are solved for the circulation of a model 14 ocean that is started from rest and driven by a specified wind stress field: westerlies at mid-latitudes and 15 easterlies in subpolar and tropical regions. -

2.011 Motion of the Upper Ocean

2.011 Motion of the Upper Ocean Prof. A. Techet April 20, 2006 Equations of Motion • Impart an impulsive force on the surface of the fluid to set it in motion (no other forces act on the fluid, except Coriolis). • Then, for a parcel of water moving with zero friction: Simplify the equations: • Assuming only Coriolis force is acting on the fluid then there will be no horizontal pressure gradients: • Assuming then the flow is only horizontal (w=0): • Coriolis Parameter: Solve these equations • Combine to solve for u: • Standard Diff. Eq. • Inertial Current Solution: (Inertial Oscillations) Inertial Current • Note this solution are equations for a circle Drifter buoys in the N. Atlantic • Circle Diameter: • Inertial Period: • Anti-cyclonic (clockwise) in N. Hemisphere; cyclonic (counterclockwise) in S. Hemi • Most common currents in the ocean! Courtesy of Prof. Robert Stewart. Used with permission. Source: Introduction to Physical Oceanography, http://oceanworld.tamu.edu/home/course_book.htm Ekman Layer • Steady winds on the surface generate a thin, horizontal boundary layer (i.e. Ekman Layer) • Thin = O (100 meters) thick • First noticed by Nansen that wind tended to blow ice at 20-40° angles to the right of the wind in the Arctic. Courtesy of Prof. Robert Stewart. Used with permission. Source: Introduction to Physical Oceanography, http://oceanworld.tamu.edu/home/course_book.htm Ekman’s Solution • Steady, homogeneous, horizontal flow with friction on a rotating earth • All horizontal and temporal derivatives are zero • Wind Stress in horizontal -

Estimates of Wind Energy Input to the Ekman Layer in the Southern Ocean from Surface Drifter Data Shane Elipot1,2 and Sarah T

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 114, C06003, doi:10.1029/2008JC005170, 2009 Click Here for Full Article Estimates of wind energy input to the Ekman layer in the Southern Ocean from surface drifter data Shane Elipot1,2 and Sarah T. Gille1,3 Received 24 October 2008; revised 19 February 2009; accepted 24 March 2009; published 5 June 2009. [1] The energy input to the upper ocean Ekman layer is assessed for the Southern Ocean by examining the rotary cross spectrum between wind stress and surface velocity for frequencies between 0 and 2 cpd. The wind stress is taken from European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts ERA-40 reanalysis, and drifter measurements from 15 m depth are used to represent surface velocities, with an adjustment to account for the vertical structure of the upper ocean. The energy input occurs mostly through the nonzero frequencies rather than the mean. Phenomenologically, the combination of a stronger anticyclonic wind stress forcing associated with a greater anticyclonic response makes the contribution from the anticyclonic frequencies dominate the wind energy input. The latitudinal and seasonal variations of the wind energy input to the Ekman layer are closely related to the variations of the wind stress, both for the mean and for the time-varying components. The contribution from the near-inertial band follows a different trend, increasing from 30°S to about 45°S and decreasing further south, possibly a consequence of the lack of variance in this band in the drifter and wind stress data. Citation: Elipot, S., and S. T. Gille (2009), Estimates of wind energy input to the Ekman layer in the Southern Ocean from surface drifter data, J. -

Intermittent Reduction in Ocean Heat Transport Into the Getz Ice Shelf

RESEARCH LETTER Intermittent Reduction in Ocean Heat Transport Into the 10.1029/2021GL093599 Getz Ice Shelf Cavity During Strong Wind Events Key Points: Nadine Steiger1,2 , Elin Darelius1,2 , Anna K. Wåhlin3 , and Karen M. Assmann4 • Observations at the western Getz Ice Shelf show eight intermittent events 1Geophysical Institute, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, 2Bjerknes Center for Climate Research, Bergen, Norway, of Winter Water deepening below 3Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 4Institute of Marine Research, 350 m depth during winter 2016 • The events are associated with Tromsø, Norway strong easterly winds and caused by non-local Ekman downwelling • The ocean heat transport into the Abstract The flow of warm water toward the western Getz Ice Shelf along the Siple Trough, West Getz Ice Shelf cavity is reduced by Antarctica, is intermittently disrupted during short events of Winter Water deepening. Here we show, 25% in the winter of 2016 due to the events using mooring records, that these 5–10 days-long events reduced the heat transport toward the ice shelf cavity by 25% in the winter of 2016. The events coincide with strong easterly winds and polynya opening in the region, but the Winter Water deepening is controlled by non-local coastal Ekman downwelling Supporting Information: Supporting Information may be found rather than polynya-related surface fluxes. The thermocline depth anomalies are forced by Ekman in the online version of this article. downwelling at the northern coast of Siple Island and propagate to the ice front as a coastal trapped wave. During the events, the flow at depth does no longer continue along isobaths into the ice shelf cavity but Correspondence to: aligns with the ice front. -

Observations of Ekman Currents in the Southern Ocean

768 JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY VOLUME 39 Observations of Ekman Currents in the Southern Ocean YUENG-DJERN LENN School of Ocean Sciences, Bangor University, Menai Bridge, Wales, United Kingdom TERESA K. CHERESKIN Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California (Manuscript received 29 October 2007, in final form 28 August 2008) ABSTRACT Largely zonal winds in the Southern Ocean drive an equatorward Ekman transport that constitutes the shallowest limb of the meridional overturning circulation of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC). Despite its importance, there have been no direct observations of the open ocean Ekman balance in the Southern Ocean until now. Using high-resolution repeat observations of upper-ocean velocity in Drake Passage, a mean Ekman spiral is resolved and Ekman transport is computed. The mean Ekman currents decay in amplitude and rotate anticyclonically with depth, penetrating to ;100-m depth, above the base of the annual mean mixed layer at 120 m. The rotation depth scale exceeds the e-folding scale of the speed by about a factor of 3, resulting in a current spiral that is compressed relative to predictions from Ekman theory. Transport estimated from the observed currents is mostly equatorward and in good agreement with the Ekman transport computed from four different gridded wind products. The mean temperature of the Ekman layer is not distinguishable from temperature at the surface. Turbulent eddy viscosities inferred from Ekman theory and a direct estimate of the time-averaged stress were O(102–103)cm2 s21. The latter calculation results in a profile of eddy viscosity that decreases in magnitude with depth and a time-averaged stress that is not parallel to the time-averaged vertical shear. -

A Coriolis Tutorial, Part 4

1 a Coriolis tutorial, Part 4: 2 wind-driven circulation and the Sverdrup relation 3 James F. Price 4 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 5 Woods Hole, Massachusetts, 02543 6 https://www2.whoi.edu/staff/jprice/ [email protected] 7 Version5.6 May23,2019 Figure 1: A zonal section through the North Atlantic thermocline at 35oN, viewed toward the north. (up- per) Sea surface height (SSH) from satellite altimetry. (lower) Potential density from in situ observations. This section shows the remarkable zonal asymmetry that is characteristic of the major ocean gyres. Within a narrow western boundary region, the SSH slope is positive and comparatively very large. The inferred geostrophic current, the Gulf Stream, is northward and fast. Over the rest of the basin, the SSH slope is negative and much smaller, and the inferred geostrophic flow is southward and very slow. This broadly distributed southerly flow is wind-driven Sverdrup flow, mainly, and is the central topic of this essay. 1 8 Abstract: This essay is the fourth of a four part introduction to the effects of Earth’s rotation on the 9 fluid dynamics of the atmosphere and ocean. The theme is wind-driven ocean circulation, and the central 10 topic is the Sverdrup relation between meridional transport and the curl of the wind stress. The goal is to 11 develop some insight for several features of the observed ocean circulation, viz. western intensification of 12 upper ocean gyres and the geography of seasonal variability. To that end, a shallow water model is solved 13 for the circulation of a model ocean that is started from rest by a specified wind stress field that includes 14 westerlies at mid-latitudes and easterlies in the lower subtropics. -

Lectures on Dynamical Meteorology

LECTURES ON DYNAMICAL METEOROLOGY Roger K. Smith Version: December 11, 2007 Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 Scales . 6 2 EQUILIBRIUM AND STABILITY 9 3 THE EQUATIONS OF MOTION 16 3.1 E®ective gravity . 16 3.2 The Coriolis force . 16 3.3 Euler's equation in a rotating coordinate system . 18 3.4 Centripetal acceleration . 19 3.5 The momentum equation . 20 3.6 The Coriolis force . 20 3.7 Perturbation pressure . 21 3.8 Scale analysis of the equation of motion . 22 3.9 Coordinate systems and the earth's sphericity . 23 3.10 Scale analysis of the equations for middle latitude synoptic systems . 25 4 GEOSTROPHIC FLOWS 28 4.1 The Taylor-Proudman Theorem . 30 4.2 Blocking . 34 4.3 Analogy between blocking and axial Taylor columns . 35 4.4 Stability of a rotating fluid . 38 4.5 Vortex flows: the gradient wind equation . 38 4.6 The e®ects of strati¯cation . 41 4.7 Thermal advection . 45 4.8 The thermodynamic equation . 46 4.9 Pressure coordinates . 47 4.10 Thickness advection . 48 4.11 Generalized thermal wind equation . 49 5 FRONTS, EKMAN BOUNDARY LAYERS AND VORTEX FLOWS 54 5.1 Fronts . 54 5.2 Margules' model . 54 5.3 Viscous boundary layers: Ekman's solution . 59 2 CONTENTS 3 5.4 Vortex boundary layers . 63 6 THE VORTICITY EQUATION FOR A HOMOGENEOUS FLUID 67 6.1 Planetary, or Rossby Waves . 68 6.2 Large scale flow over a mountain barrier . 74 6.3 Wind driven ocean currents . 75 6.4 Topographic waves .