The Cinematic Experience.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![CD Booklet W/ Essays [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3775/cd-booklet-w-essays-pdf-1773775.webp)

CD Booklet W/ Essays [PDF]

+ / vs. 01 | Booklet 4/10/02 6:46 PM Page 1 Komet + / vs. Bovine Life Introduction » Introduction Bovine Life» Bovine 2 reciprocal R designers Fehler. Fällt by artwork and features (Fällt) Murphy and Christopher by R work(s). other’s ofeach a remix w w contributing acollaborative assemblers sound two installmentfeatures This first them. between of musicalreciprocality and documenting theprocess assemblers sound of two thework(s) featuring split CDs R Fä with inassociation BiP-HOp by 4 ofchanges. orseries operation 3 orcourse ofsomething. progress otheroperation. or some s a esp. action orprocedure, process complementary. correspondent; eries ofstages inmanufacture eries eciprocess +/vs. eciprocess eciprocess + / vs. isco-curated +/vs. eciprocess of Aseries +/vs. eciprocess a natural orinvoluntary a natural orks; and finally, contributing orks; andfinally, ofindependentork; aseries mutual. (computing) on(data) operate llt are pleased topresent llt are I was in a record shop in my There are boundaries, but it’s as I was very keen that this was Philippe Petit (BiP-HOp) (BiP-HOp) Philippe Petit ofaprogram. means home town of Edinburgh - if the creator of the music has going to be a collaboration Avalanche - when I first heard set up the track like a science forged strictly over the net, so n. +v. 3 adj. +n. adj. Frank Bretschneider’s music. project - tamed the chaos, and we both sent each other inversely I loved it. then put the lid on the sound. economical .mp3 files to fashion 1 into new material. While this a course of I was struck by it’s exacting All this (warm) military precision method of working wasn’t 1 I was in a record shop in my in return. -

15 – 18 November 2012 SOUND EXCHANGE FESTIVAL Chemnitz Experimental Music Cultures in Central Europe a Project by Dock E.V

PRESS RELEASE 10/2012 October 2012 15 – 18 November 2012 SOUND EXCHANGE FESTIVAL Chemnitz Experimental Music Cultures in Central Europe A project by Dock e.V. and the Goethe-Institut, funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation. Concerts, Performances, Exhibition, Sound Installation and Film in weltecho, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, Neue Sächsische Galerie, Atomino Improvised and experimental music, jazz and New Music all have a long tradition in Central and Eastern Europe. For decades, the protagonists of these very different and highly diverse music scenes worked under extremely difficult conditions. They were subject to repression by the authorities and were mostly compelled to practice their art in secret. Free spirits in the arts were eyed with no less suspicion than political dissidents. Following the upheavals in the late 80’s and early 90’s, many local music traditions in Central and Eastern Europe fell into complete oblivion. The appeal of the West was too strong, the new digital developments too interesting. Starting 2011, the festival project SOUND EXCHANGE sets out in search of the origins and the present of experimental music culture in Central Europe, to follow the trail of a vital and internationally interlinked scene of musicians, artists and festivals. SOUND EXCHANGE makes vanished traditions audible and visible, and situates them in relationship to current developments in local music scenes. The SOUND EXCHANGE FESTIVAL Chemnitz in mid-November 2012 is the concluding station of the project as a whole that was organised by DOCK e.V. Berlin and the Goethe- Institut in cooperation with weltecho in Chemnitz, and is funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation. -

Conrad Schnitzler & Frank Bretschneider

Conrad Schnitzler & Frank Bretschneider Con-Struct CD / LP / Digital Release: 07. August 2020 About Conrad Schnitzler Conrad Schnitzler is one of the great pioneers of electronic music. There was a particular type of artist who could only have emerged in the legendary early 1970s. Few musicians fit the bill better than Conrad Schnitzler. Revolution, pop art and Fluxus created a climate which engendered unbridled artistic and social development. Radical utopias, excessive experimentation with drugs, ruthless (in a positive way) transgression of aesthetic frontiers were characteristic of the period. The magic words were “subculture”, “progressivity” and “avantgardism”. As an acolyte of action and object artist Joseph Beuys, Schnitzler embraced the former’s “extended definition of art”, in which controlled randomness assumed an important role. Schnitzler actually extended the concept of “music”. Or to put it another way: he cared not one iota for existing rules of music, preferring to create his own or conceptualizing a certain degree of lawlessness. In the first half of the 80s young pop musicians discovered the true potential of Schnitzler’s radical musical concept. Henceforth, his name was quoted with increasing regularity in the same breath as industrial, new wave and other experimental music genres of the 1980s. Schnitzler’s style was really too idiosyncratic ever to set a precedent, but he was, and still is, one of the most significant inspirations for pop music in more recent times. Already a figure of prominence, perhaps he will one day be elevated to the status of a legend. About Frank Bretschneider Frank Bretschneider is a musician, composer and video artist in Berlin. -

Pw Press Release

PW PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jennifer Benz Joy Public Relations Associate 212.421.3292 www.pacewildenstein.com Fades , 2006 THREE CONSECUTIVE EVENINGS IN OCTOBER DEVOTED TO ARTIST AND MUSICIAN CARSTEN NICOLAI EXHIBITION OPENING AT PACEWILDENSTEIN FOLLOWED BY LECTURE AT GOETHE-INSTITUT AND PERFORMANCE AT THE KITCHEN NEW YORK, September 24, 2007— PaceWildenstein is pleased to present new work by Carsten Nicolai in an exhibition entitled static balance from October 5 through November 3, 2007 at 534 West 25th Street, New York City. The artist will be present at a public reception held on Thursday, October 4 th from 6-8 p.m. Carsten Nicolai’s fusion of art and music has led to exhibitions and performances worldwide. static balance , Nicolai’s first exhibition with PaceWildenstein, blends electronic sounds and visual effects into highly energized environments that engage sensory perceptions. The PaceWildenstein opening is the first of three consecutive evenings devoted to the artist’s work in New York City. On Friday, October 5 th at 6:30 p.m., The Goethe-Institut, 1014 Fifth Avenue at 83 rd Street, will host a discussion between Nicolai and curator Gregory Volk about the artist’s newest work. Admission is free and open to the public. The following evening Saturday, October 6 at 8 p.m. Nicolai (a.k.a. alva noto) will present Xerrox vol. 2 . Created from a variety of ordinary source material ranging from Muzak to television advertising melodies, Nicolai will use a laptop to compress, multiply, and alter this digital information into a video projection of sonic visual abstraction. -

12Abc3d Ef4ghi5j Kl6mno7 Pqrs8tu V9wxyz

PROGRAMME 12ABC3D EF4GHI5J KL6MNO7 PQRS8TU V9WXYZ unsorted, SonicActsX Many new art forms have emerged The information arts are the theme in recent years (from business art to of unsorted, SonicActsX. The festi- genomic art and from computer art val takes place from Thursday 23rd to neo-conceptualism) which in form until Saturday September 25th and content are rooted in the infor- at Paradiso, Amsterdam. It consists mation society: the information arts. of three consecutive afternoons and These information arts defy several nights of live performances, a film paradigms on which traditional art programme, a two-day conference, forms are based. and an exhibition. PROGRAMME, 23rd September PROGRAMME, 24th September unsorted am/pm am/pm doors open . from 20:00–04:00 tobias c. van Veen . .CONFERENCE . .S . .16:00–16:45 MIMEO . .SPECIALS . .M . .20:30–00:15 CM von Hausswolff . .CONFERENCE . .S . .16:45–17:30 The Story of Computer Graphics . .FILM . .S . .20.30–22:00 Jon Wozencroft . .CONFERENCE . .S . .17:30–18:15 Meta . .LIVE CINEMA . .S . .22.45–23.30 Tom Betts & Joe Gilmore . .CONFERENCE . .S . .18:15–19:00 GAS DVD Night part 1 . .FILM . .S . .23.30–00:00 Abstract Cinema . .FILM . .S . .20:30–21:30 mise-en-trôpes . .LIVE CINEMA . .S . .00:00–00:45 CM von Hausswolff . .RASTER-NOTON . .M . .21:00–21:45 Radian & Jade . .LIVE CINEMA . .M . .00:15–01:00 Pixel . .RASTER-NOTON . .M . .21:45–22:30 GAS DVD Night part 2 . .FILM . .S . .00:45–01:15 Codespace . .LIVE CINEMA . .S . .22:15–23:00 Battery Operated . -

Aiff-Tiff.Pdf

raster-noton a i f f – t i f f raster-noton a i f f – t i f f olaf bender and frank bretschneider founded the record label rastermusic in 1996. it merged with carsten nicolai’s label noton . archiv alva noto 04 für ton und nichtton to form raster-noton . archiv für ton und nichtton in 1999. its head office is located in chemnitz, germany. cyclo. 16 frank bretschneider 26 raster-noton is meant to be a platform — a network covering the overlapping border areas of pop, art and science. the label real- nibo 36 izes music projects, publications and installation works. the common idea behind all releases is an experimental approach — an byetone 44 amalgamation of sound, art and design. signal 54 1996 年,オラフ・ベンダーとフランク・ブレットシュナイダーが共にレコードレーベル rastermusic を設立。1999 年,同レーベルがカールステン・ニコライの レーベル noton . archiv für ton und nichtton と合併し,raster-noton . archiv für ton und nichtton が設立された。その本部はドイツのケムニッツにある。 raster-noton はポップ,芸術,科学が交差する境界線をカバーするネットワークであり , そのプラットフォームとなることを企図されている。本レーベルは音楽 , 出版物 , インスタレーション作品を扱い,すべてのリリース作品はその背後に実験的な姿勢,すなわちサウンド,アート,デザインの融合という理念を共有している。 4 5 unitxt xerrox alva noto unitxt | xerrox unitxt — the title unitxt could be read as ‘unit extended’ – referring to a unit of a rhythmic grid – or ‘universal text’ – referring to a unitxt ̶̶ リズムの音節単位に言及する「unit extended(拡張された単位)」とも,数学の単位,定数,計測値,接頭辞,乗数のような普遍的な言語を指す「universal universal language, e.g. mathematics: units, constants, measurements, prefix-, SI system of units – and is represented in spoken text(普遍的なテキスト)」とも読める題名のこの作品は, 話された言葉に基づき,音自体を記号的に用いて表現されている。『unitxt』のヴィジュアルは,ソフトウ word and by codes in sound itself. the visuals of unitxt are based on the real-time manipulation / modulation of software-generated ェアによって生成された音声信号によるテストパターンを,リアルタイムに変調させることで制作された。それゆえ,生成される画像はつねに変化し,同じものが test patterns by an audio signal. -

Carsten Nicolai

Carsten Nicolai 1 2 Carsten Nicolai audio visual spaces 3 4 Inhoudstafel | Contents 7 Brief aan Carsten Nicolai 8 Letter to Carsten Nicolai Philippe Van Cauteren 13 Kijken met de oren: Enkele aandachtspunten bij Carsten Nicolai’s geluidswerk 21 Seeing with the Ear: Some Points of Focus in Carsten Nicolai’s Sound Work Ive Stevenheydens 33 Het essentiële assembleren voor een opmerkelijke reis 37 Assembling the essentials for a remarkable trip Carl Michael von Hausswolff 51 De golven vangen. De ‘Klangfiguren’ van Carsten Nicolai 59 Catching the Waves. Carsten Nicolai’s ‘Klangfiguren’ Antonio Somaini 85 Lijst van werken opgenomen in de tentoonstelling List of works in exhibition 5 6 Brief aan Carsten Nicolai Ik weet niet of ik je een kunstenaar kan noemen. Misschien ben je veeleer een weten- schapper of een musicus. Een meticuleus onderzoeker voor wie het museum een laboratorium wordt en de kunstwerken analytische instrumenten en waarnemings- modules. Wiskundige principes, fractalen en natuurkundige fenomenen sturen jouw analytisch beeldend denken. In de hedendaagse kunst is het een terugkerende démarche de relatie tussen woord en beeld te onderzoeken. Veel minder – of minder vaak – zijn beeldend kunstenaars begaan met geluid en vorm. In uitgepuurde streng esthetische ‘testsituaties’ maak jij echter verborgen mechanismen en principes uit de natuur zichtbaar die geluid visualiseren, ontrafel je frequenties, dissecteer je visuele prikkels, of tracht je geluid vast te houden. Toen ik vernam dat het kunsten- centrum Vooruit in Gent Raster-Noton (Olaf Bender, Frank Bretschneider, Carsten Nicolai) voor een maand te gast heeft, was mijn onmiddellijke reflex een deel van het S.M.A.K. -

CARSTEN NICOLAI UNIDISPLAY 2 Hangarbicocca

Carsten Nicolai 1 CARSTEN NICOLAI UNIDISPLAY 2 HangarBicocca In copertina/Cover page unidisplay, 2012 [Foto di/Photo by Richard-Max Tremblay] CARSTEN NICOLAI UNIDISPLAY Fondazione HangarBicocca Via Chiese 2 20126 Milano a cura di Chiara Bertola e Andrea Lissoni curated by Chiara Bertola and Andrea Lissoni Orari Opening hours giovedì / domenica Thursday to Sunday 11.00 – 23.00 11 am – 11 pm Testi di/Texts by Giovanna Amadasi lunedì / mercoledì Monday to Wednesday chiuso closed INGREsso libERO FREE ENTRancE Contatti Contacts Tel +39 02 66111573 T. +39 02 66111573 [email protected] [email protected] hangarbicocca.org hangarbicocca.org 4 HangarBicocca Carsten Nicolai 5 inTRoduZionE Carsten Nicolai, la cui identità sfugge volutamente alle rigide definizioni di “artista visivo”, “musicista”, “produttore”, è una figura di fondamentale importanza per la comprensione della scena culturale di ricerca degli ultimi quindici anni. Il suo percorso, infatti, si intreccia strettamente con la diffu- sione nella seconda metà degli anni ’90 di una cultura digitale che influenza le modalità di produzione e creazione nell’am- bito musicale, visivo e progettuale. Grazie all’accessibilità - per la prima volta nella storia - di tecnologie sofisticate alla portata di tutti, una nuova generazione di artisti, compositori, dj, architetti, videomaker e grafici crea e utilizza software in grado di dare vita a un immaginario completamente inedito e ibridato, condividendo pratiche, competenze, stili in modo fino ad allora impensabile. A Berlino, in particolare, in seguito al fermento sociale favo- rito dall’apertura delle frontiere con l’Est Europa, si genera una scena che permea il mondo della musica dance e dei club, influenzando in modo decisivo anche campi quali il design, la moda e l’arte e segnando così uno dei momenti culturali più innovativi degli ultimi decenni in Europa. -

For Immediate Release Datumsoria: an Exhibition of LIU Xiaodong

For immediate release Datumsoria: An Exhibition of LIU Xiaodong, Carsten Nicolai, and Nam June Paik A Project of A&T@ Opening reception: 17.09.2016 On view: 18.09.2016-30.12.2016 Venue: Chronus Art Center Address:BLDG.18, NO.50 Moganshan Road, Shanghai, China Chronus Art Center is pleased to announce the much-anticipated presentation of Datumsoria: An Exhibition of LIU Xiaodong, Carsten Nicolai, and Nam June Paik. A neologism, Datumsoria conjugates datum and sensoria, denoting a new perceptual space immanent to the information age. Upon entering the gallery, the audience is first greeted by a Genghis Khan of the 20th century transformed in a tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nam June Paik to amusingly pedal a bicycle rather than majestically command from horseback. Topped by a diving helmet, the prince’s torso is a patchwork made from a fuel dispenser conjoined with plastic pipe limbs. Loaded in the back of his overburdened vehicle is a pile of television cases stacked on top of each other encasing symbols, characters made of neon lights, intimating the transmission of encrypted messages through an electronic pathway. A screen that is embedded inside a hollowed-out part of the fuel-dispenser displays video images that morph from mundane objects to a pyramid of ancient glory. Created in 1993, the year when the first graphic web browser Mosaic was launched making the long-promised information superhighway a material reality, Rehabilitation of Genghis-Khan intuitively resonated with the coming of a new historical epoch in which the entire human experience would soon be transformed by the instantaneity and simultaneity of network immediacy, the gargantuanization of processing power and the nanonization of storage media. -

A Sound Legacy? Music and Politics in East Germany

Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program Series Volume 8 A SOUND LEGACY? MUSIC AND POLITICS IN EAST GERMANY Edited by Edward Larkey University of Maryland American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program Series Volume 8 A SOUND LEGACY? MUSIC AND POLITICS IN EAST GERMANY Edited by Edward Larkey University of Maryland The American Institute for Contemporary German Studies (AICGS) is a center for advanced research, study and discussion on the politics, culture and society of the Federal Republic of Germany. Established in 1983 and affiliated with The Johns Hopkins University but governed by its own Board of Trustees, AICGS is a privately incorporated institute dedicated to independent, critical and comprehensive analysis and assessment of current German issues. Its goals are to help develop a new generation of American scholars with a thorough understanding of contemporary Germany, deepen American knowledge and understanding of current German developments, contribute to American policy analysis of problems relating to Germany, and promote interdisciplinary and comparative research on Germany. Executive Director: Jackson Janes Board of Trustees, Cochair: Steven Muller Board of Trustees, Cochair: Harry J. Gray The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©2000 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-53-9 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. -

E M E 0 8 / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Dossier a R T I S T a S 2 0

E M E 0 8 / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Dossier A R T I S T A S 2 0 0 8 / / / / / / / / / / / / C O N C E R T O S – M U S I C O S e A R T I S T A S V I S U A I S / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / NNY (Portugal) GARCIA, MACHAS, MARANHA E MOTA (Portugal) THE BEAUTIFUL SCHIZOPHONIC (Portugal) SAFE & SOUND (Portugal) THE SIGHT BELOW ( (Estados Unidos) GREG HAINES (Inglaterra) HAUSCHKA (Alemanha) ANNA TROISI (Itália) SANSO-XTRO (Austrália) FRANK BRETSCHNEIDER (Alemanha) CARSTEN GOERTZ (Alemanha) TINA FRANK (Áustria) / / / / / / / / / / / / / / I N S T A L A Ç Õ E S / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / CARSTEN GOERTZ (Alemanha) ANDRÉ SIER (Portugal) TINA FRANK (Áustria) ANDRÉ GONÇALVES (Portugal) Alunos do Curso de Artes Digitais e New Media da Restart (Portugal) / / / / / / / / / / / W O R K S H O P, M A S T E R C L A S S E E N C O N T R O C O M A R T I S T A / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / CARSTEN GOERTZ (Alemanha) TINA FRANK (Áustria) FRANK BRETSCHNEIDER (Alemanha) NNY (Portugal) www.myspace.com/earational www.nothing.scene.org/nny NNY is the recording and performing name of Jerome Faria (b. 1983), a sound and visual artist based in Madeira, Portugal. Aside from a vast background as a musician in many bands, he released his first solo work signed as NNY in 2004: the "OFFEAR.EP" on Enough Records. That piece, quoted by the label as "brilliant experimental idm ambient", was followed by the first full-length album "ECT" in 2005 on Test Tube Records which described it as "a complex experiment in sound dissection, as Jerome pursues pure forms of sound composition, some being harsh and brute while others are harmonious and contemplating." 2006 saw the release of the highly conceptual record "COIL" on MiMi Records. -

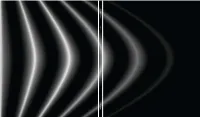

Cnicolai Fades.Pdf

carsten nicolai fades inside the black box a black box is a space or device in which inner functionality and mechanisms are on the inner process of the black box rather than its outcome. the consequence kept in the dark. the only concern lies in the result of the process between input and is far-reaching on many levels—the results are both perceptive and conceptive in output. bruno latour quotes that »when a machine runs efficiently, when a matter character. of fact is settled, one need focus only on its inputs and outputs and not on its inter- nal complexity. thus, paradoxically, the more science and technology succeed, the entering the room, we first seem to be surrounded by darkness. the only thing per- more opaque and obscure they become«*. this can be interpreted in a more philo- ceivable is a surrounding, high hissing white noise sound that in- and decreases sophical and cultural sense, where accordingly, a process, no matter what content while also changing from side to side of the room. as soon as our eyes get used it may convey, lacks further reflection, promotes indifference, and thereby supports to the light conditions, we slowly become aware of the space that is filled with a ignorance towards its purpose and impact. soft haze of mist. congruent to the sound, a gradually varying projection of light is permeating through the room. the rays of light from the projection form continually in contrast, a work of art establishes manifold new perspectives on processes, fading shapes that constantly change their flow through the haze, thus building up events, and apparent facts that are normally hidden under the surface of everyday a permanently changing light architecture.