An Alternative Reading of Warhol's Early Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Affective Temporalities in Gob Squad’S Kitchen (You’Ve Never Had It So Good)

56 ANA PAIS AFFECTIVE TEMPORALITIES IN GOB SQUAD’S KITCHEN (YOU’VE NEVER HAD IT SO GOOD) In this article I will be drawing upon affect theory to unpack issues of authenticity, mediation, participation in the production Gob Squads’s Kitchen, by Gob Squad. English/German collective reconstructed Andy Warhol’s early film Kitchen, shot 47 years before, in the flamboyant Factory, starring ephemeral celebrities such as Eve Sedgwick. Alongside Eat (1964), Sleep (1963) and Screen Test (1964-66). Although it premièred in Berlin, in 2007, the show has been touring in several countries and, in 2012, it received the New York Drama Desk Award for Unique Theatrical Experience.I will be examining how the production’s spatial dispositive creates a mediated intimacy that generates affective temporalities and how their performativity allows us to think of the audience as actively engaged in an affective resonance with the stage. Intimacy creates worlds (Berlant 2000). It brings audience and performer closer not only to each other but also to the shifting moment of Performance Art’s capture by institutional discourses and market value. Unleashing affective temporalities allows the audience to embody its potency, to be, again, “at the beginning”.Drawing upon André Lepecki’s notion of reenactments as activations of creative possibilities, I will be suggesting that Gob Squads’s Kitchen merges past and present by disclosing accumulated affects, promises and deceptions attached to the thrilling period of the sixties in order to reperform a possibility of a new beginning at the heart of a nowthen time. In conclusion, this article will shed new light on the performative possibilities of affect to surmount theatrical separation and weave intensive attachments. -

NO RAMBLING ON: the LISTLESS COWBOYS of HORSE Jon Davies

WARHOL pages_BFI 25/06/2013 10:57 Page 108 If Andy Warhol’s queer cinema of the 1960s allowed for a flourishing of newly articulated sexual and gender possibilities, it also fostered a performative dichotomy: those who command the voice and those who do not. Many of his sound films stage a dynamic of stoicism and loquaciousness that produces a complex and compelling web of power and desire. The artist has summed the binary up succinctly: ‘Talk ers are doing something. Beaut ies are being something’ 1 and, as Viva explained about this tendency in reference to Warhol’s 1968 Lonesome Cowboys : ‘Men seem to have trouble doing these nonscript things. It’s a natural 5_ 10 2 for women and fags – they ramble on. But straight men can’t.’ The brilliant writer and progenitor of the Theatre of the Ridiculous Ronald Tavel’s first two films as scenarist for Warhol are paradigmatic in this regard: Screen Test #1 and Screen Test #2 (both 1965). In Screen Test #1 , the performer, Warhol’s then lover Philip Fagan, is completely closed off to Tavel’s attempts at spurring him to act out and to reveal himself. 3 According to Tavel, he was so up-tight. He just crawled into himself, and the more I asked him, the more up-tight he became and less was recorded on film, and, so, I got more personal about touchy things, which became the principle for me for the next six months. 4 When Tavel turned his self-described ‘sadism’ on a true cinematic superstar, however, in Screen Test #2 , the results were extraordinary. -

Warhol, Andy (As Filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol

Warhol, Andy (as filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol. by David Ehrenstein Image appears under the Creative Commons Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Jack Mitchell. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com As a painter Andy Warhol (the name he assumed after moving to New York as a young man) has been compared to everyone from Salvador Dalí to Norman Rockwell. But when it comes to his role as a filmmaker he is generally remembered either for a single film--Sleep (1963)--or for works that he did not actually direct. Born into a blue-collar family in Forest City, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, Andrew Warhola, Jr. attended art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He moved to New York in 1949, where he changed his name to Andy Warhol and became an international icon of Pop Art. Between 1963 and 1967 Warhol turned out a dizzying number and variety of films involving many different collaborators, but after a 1968 attempt on his life, he retired from active duty behind the camera, becoming a producer/ "presenter" of films, almost all of which were written and directed by Paul Morrissey. Morrissey's Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972) are estimable works. And Bad (1977), the sole opus of Warhol's lover Jed Johnson, is not bad either. But none of these films can compare to the Warhol films that preceded them, particularly My Hustler (1965), an unprecedented slice of urban gay life; Beauty #2 (1965), the best of the films featuring Edie Sedgwick; The Chelsea Girls (1966), the only experimental film to gain widespread theatrical release; and **** (Four Stars) (1967), the 25-hour long culmination of Warhol's career as a filmmaker. -

California State University, Northridge Exploitation

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE EXPLOITATION, WOMEN AND WARHOL A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art by Kathleen Frances Burke May 1986 The Thesis of Kathleen Frances Burke is approved: Louise Leyis, M.A. Dianne E. Irwin, Ph.D. r<Iary/ Kenan Ph.D. , Chair California State. University, Northridge ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Dr. Mary Kenon Breazeale, whose tireless efforts have brought it to fruition. She taught me to "see" and interpret art history in a different way, as a feminist, proving that women's perspectives need not always agree with more traditional views. In addition, I've learned that personal politics does not have to be sacrificed, or compartmentalized in my life, but that it can be joined with a professional career and scholarly discipline. My time as a graduate student with Dr. Breazeale has had a profound effect on my personal life and career, and will continue to do so whatever paths my life travels. For this I will always be grateful. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In addition, I would like to acknowledge the other members of my committee: Louise Lewis and Dr. Dianne Irwin. They provided extensive editorial comments which helped me to express my ideas more clearly and succinctly. I would like to thank the six branches of the Glendale iii Public Library and their staffs, in particular: Virginia Barbieri, Claire Crandall, Fleur Osmanson, Nora Goldsmith, Cynthia Carr and Joseph Fuchs. They provided me with materials and research assistance for this project. I would also like to thank the members of my family. -

1 Bufferin Commercial Gary Needham Bufferin Commercial Refers in Its

Bufferin Commercial Gary Needham Bufferin Commercial refers in its title to a widely available brand of aspirin. The film is also typical of some of Warhol’s filmmaking practices in 1966 and, I will argue, anticipates Warhol’s philosophy on relations between business and art. In addition to offering some commentary on this relatively unknown film I also want to use Bufferin Commercial to explore some possible ways to explain and account for those filmmaking practices that Warhol described circa 1966 as being deliberately bad; Warhol pretended to be both incompetent and curious about the process of making films and even made a statement on network television advocating ‘bad camerawork.’1 Bufferin Commercial shouldn’t be confused with the other Bufferin (1966), the portrait film Warhol made in collaboration with Gerard Malanga and the subject of Jean Wainwright’s chapter in this volume. Bufferin Commercial is comprised of two 1200 foot thirty-three minute reels. The first reel is without sound (an unintentional accident) and the second reel has sound. There is some uncertainty surrounding the film’s projection history as being either a single screen 66 minute film, listed as 70 minutes in The Filmmaker’s Cooperative Catalogue No.4 (1967), or a double screen projection that would be 33 minutes in duration.2 It was filmed on Wednesday, 14 December 1966 with two cameras that ran simultaneously, one of them operated by Warhol and the other by Paul Morrissey. Bufferin Commercial’s absence from commentary on Warhol’s films may be due to it being one of the few of his sixties films that was an outside agency commission organised by Richard Frank from the Grey advertising agency in New York on behalf of the pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers. -

Chelsea Girls Free

FREE CHELSEA GIRLS PDF Eileen Myles | 288 pages | 29 Sep 2015 | Ecco Press | 9780062394668 | English | United States Chelsea Girl (album) - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. From the dramatic redbrick facade to the sweeping staircase dripping with art, the Chelsea Hotel has long been New York City's creative oasis for the many artists, writers, musicians, actors, filmmakers, and poets who have called it home—a scene Chelsea Girls Hazel Riley and actress Maxine Mead are determined to Chelsea Girls to their advantage. Yet they soon discover that the greatest obstacle to putting up a show on Broadway has nothing to do with their art, and everything to do with politics. A Red scare Chelsea Girls sweeping across America, and Senator Joseph McCarthy has started a witch hunt for Communists, with those in the entertainment industry in the crosshairs. As the pressure builds to Chelsea Girls names, it Chelsea Girls more than Hazel and Maxine's Broadway dreams that may suffer as they grapple with Chelsea Girls terrible consequences, but also their livelihood, their friendship, and even their freedom. Spanning from the s to the s, The Chelsea Girls deftly pulls back the curtain on the desperate political pressures of McCarthyism, the complicated bonds of female friendship, and the siren call of the uninhibited Chelsea Hotel. -

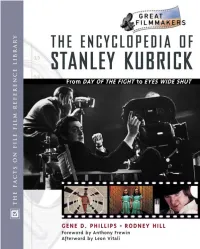

The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK GENE D. PHILLIPS RODNEY HILL with John C.Tibbetts James M.Welsh Series Editors Foreword by Anthony Frewin Afterword by Leon Vitali The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick Copyright © 2002 by Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hill, Rodney, 1965– The encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick / Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill; foreword by Anthony Frewin p. cm.— (Library of great filmmakers) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4388-4 (alk. paper) 1. Kubrick, Stanley—Encyclopedias. I. Phillips, Gene D. II.Title. III. Series. PN1998.3.K83 H55 2002 791.43'0233'092—dc21 [B] 2001040402 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K.Arroyo Cover design by Nora Wertz Illustrations by John C.Tibbetts Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

A Quarterly Magazine of Art and Culture Issue 8 Fall 2002 Us $8

A quArterly mAgAzine of Art And culture issue 8 Fall 2002 CABINET US $8 CanAdA $13 uK £6 cabinet All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction of any material here is a no-no. The views published in this magazine are not necessarily those of the writers, Immaterial Incorporated let alone the cowardly editors of Cabinet. 181 Wyckoff Street Brooklyn NY 11217 USA tel + 1 718 222 8434 Erratum: fax + 1 718 222 3700 We offer apologies to Tricia Keightley and Karen Arm whose paintings were email [email protected] reproduced on page 27 of issue 7 in the wrong orientation. www.immaterial.net Cover: Reed Anderson, Sour Serenade (detail), 2000. Courtesy Pierogi Gallery. Editor-in-chief Sina Najafi Page 4: Undercover narcotics officer posing as a “hippie” in 1968. Courtesy Senior editor Jeffrey Kastner AP Photos. Editors Frances Richard, David Serlin, Gregory Williams CD editor Brian Conley Art directors (Cabinet Magazine) Ariel Apte and Sarah Gephart of mgmt. Art director (Immaterial Incorporated) Richard Massey/OIG Editors-at-large Saul Anton, Mats Bigert, Jesse Lerner, Allen S. Weiss, Jay Worthington Website Kristofer Widholm and Luke Murphy Image editor Naomi Ben-Shahar Production manager Sarah Crowner Development consultant Alex Villari Contributing editors Joe Amrhein, Molly Bleiden, Eric Bunge, Andrea Codrington, Christoph Cox, Cletus Dalglish-Schommer, Pip Day, Carl Michael von Hausswolff, Srdjan Jovanovic Weiss, Dejan Krsic, Tan Lin, Roxana Marcoci, Ricardo de Oliveira, Phillip Scher, Rachel Schreiber, Lytle Shaw, Debra Singer, Cecilia Sjöholm, Sven-Olov Wallenstein Graphic design assistants Jessica Green & Emelie Bornhager Proofreaders Joelle Hann & Catherine Lowe Research assistants Sasha Archibald, Amoreen Armetta, Ernest Loesser, Normandy Sherwood Prepress Zvi @ Digital Ink Founding editors Brian Conley and Sina Najafi Printed in Belgium by Die Keure Cabinet (ISSN 1531-1430) is a quarterly magazine published by Immaterial Incorporated, 181 Wyckoff Street, Brooklyn NY 11217. -

Historic Context Statement for LGBT History in New York City

Historic Context Statement for LGBT History in New York City PREPARED FOR MAY 2018 Historic Context Statement for LGBT History in New York City PREPARED BY The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project: Jay Shockley, Amanda Davis, Ken Lustbader, and Andrew Dolkart EDITED BY Kathleen Howe and Kathleen LaFrank of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation PREPARED FOR The National Park Service and the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation Cover Image: Participants gather at the starting point of the first NYC Pride March (originally known as Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day) on Washington Place between Sheridan Square and Sixth Avenue, June 28, 1970. Photo by Leonard Fink. Courtesy of the LGBT Community Center National History Archive. Table of Contents 05 Chapter 1: Introduction 06 LGBT Context Statement 09 Diversity of the LGBT Community 09 Methodology 13 Period of Study 16 Chapter 2: LGBT History 17 Theme 1: New Amsterdam and New York City in the 17th and 18th Centuries 20 Theme 2: Emergence of an LGBT Subculture in New York City (1840s to World War I) 26 Theme 3: Development of Lesbian and Gay Greenwich Village and Harlem Between the Wars (1918 to 1945) 35 Theme 4: Policing, Harassment, and Social Control (1840s to 1974) 39 Theme 5: Privacy in Public: Cruising Spots, Bathhouses, and Other Sexual Meeting Places (1840s to 2000) 43 Theme 6: The Early Fight for LGBT Equality (1930s to 1974) 57 Theme 7: LGBT Communities: Action, Support, Education, and Awareness (1974 to 2000) 65 Theme -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The assumption of Lupe Velez / Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9gd07500 Author Gonzalez, Rita Aida Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Assumption of Lupe Velez A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Visual Arts by Rita Aida Gonzalez Committee in charge: Professor Steve Fagin, Chair Professor Anthony Burr Professor Grant Kester Professor John Welchman 2014 The Thesis of Rita Aida Gonzalez is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. v Abstract of the Thesis ........................................................................................................ ix Chapter One ........................................................................................................................ 1 Background to the Making of the Assumption of Lupe -

A Bibliography THESIS MASTER of ARTS

3 rlE NO, 6 . Articles on Drama and Theatre in Selected Journals Housed in the North Texas State University Libraries: A Bibliography THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Jimm Foster, B.A. Denton, Texas December, 1985 Foster, Jimm, Articles on Drama and Theatre in Texas State Selected Journals Housed in the North Master of Arts University Libraries: A Bibliography. 33 (Drama), December, 1985, 436 pp., bibliography, titles. The continued publication of articles concerning has drama and theatre in scholarly periodicals to the resulted in the "loss" of much research due to lack of retrieval tools. This work is designed the articles partially fill this lack by cassifying Trussler's found in fourteen current periodicals using taxonomy. Copyright by Jimm Foster 1985 ii - - - - - - - - - -- - -- - - - 4e.1J.metal,0..ilmis!!,_JGhiin IhleJutiJalla 's.lltifohyf;')Mil ;aAm"d="A -4-40---'+ .' "--*-0- -'e-"M."- - '*- -- - - -- - -" "'--- -- *- -"- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page * . - . v INTRODUCTION Chapter . - . - - - . I. REFERENCE - '. 1 OF THE 10 II. STUDY AND CRITICISM 10 PERFORMING ARTS . .. *. - - - * - 23 III. THEATRE AND EDUCATION IV. ANCIENT AND CLASSICAL DRAMA 6161-"-" AND THEATRE.. 67 THEATRE . - - - * V. MODERN DRAMA AND THEATRE . " - - 70 VI. EUROPEAN DRAMA AND THEATRE . * . - 71 VII. ITALIAN DRAMA AND THEATRE . - - 78 VIII. SPANISH DRAMA AND 85 THEATRE . - . IX. FRENCH DRAMA AND . 115 AND THEATRE . - - X. GERMAN DRAMA AND DUTCH DRAMA 130 XI. BELGIAN - 1 AND THEATRE . - THEATRE . " - - 133 XII. AUSTRIAN DRAMA AND 137 THEATRE . - - - XIII. SWISS DRAMA AND DRAMA XIV. EASTERN EUROPEAN ANDTHEATRE . -. 140 THEATRE . 147 XV. MODERN GREEK DRAMA AND 148 AND THEATRE . -

Andy Warhol 12/28/07 10:26 PM

Andy Warhol 12/28/07 10:26 PM contents great directors cteq annotations top tens about us links archive search Andy Warhol Andrew Warhola b. August 6, 1928, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA d. February 22, 1987, New York, New York, USA by Constantine Verevis Constantine Verevis teaches in the School of Literary, Visual and Performance Studies at Monash University, Melbourne. filmography bibliography articles in Senses web resources When people describe who I am, if they don't say, 'Andy Warhol the Pop artist,' they say, 'Andy Warhol the underground filmmaker.' Andy Warhol, POPism Andy Warhol was not only the twentieth century's most “famous” exponent of Pop art but, “a post-modern Renaissance man”: a commercial illustrator, a writer, a photographer, a sculptor, a magazine editor, a television producer, an exhibition curator, and one of the most important and provocative filmmakers of the New American Cinema group of the early 1960s. (1) The influence of Warhol's filmmaking can be found in both the Hollywood mainstream film, which took from his work a “gritty street-life realism, sexual explicitness, and on-the-edge performances,” and in experimental film, which “reworked his long-take, fixed-camera aesthetic into what came to be known as structural film.” (2) At the beginning of the 1960s Warhol emerged as a significant artist in the New York art scene, his first Manhattan show – at the Stable Gallery in the fall of '62 – featuring Coca- Cola, Dance Diagram, Do It Yourself, Elvis, Marilyn and disaster paintings. In 1963 Warhol established a work space in a vacant firehouse – a hook and ladder company – on East 87th Street, and later that same year moved his studio to 231 East 47th Street, the space which came to be known as the Factory.