A Turn to the Politics of Place in Hong Kong Independent Documentaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Translation) Minutes of the 23 Meeting of the 4 Wan Chai District

(Translation) Minutes of the 23rd Meeting of the 4th Wan Chai District Council Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Date: 7 July 2015 (Tuesday) Time: 2:30 p.m. Venue: District Council Conference Room, Wan Chai District Office, 21/F Southorn Centre, 130 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, H.K. Present Chairperson Mr SUEN Kai-cheong, SBS, MH, JP Vice-Chairperson Mr Stephen NG, BBS, MH, JP Members Ms Pamela PECK Ms Yolanda NG, MH Ms Kenny LEE Ms Peggy LEE Mr Ivan WONG, MH Mr David WONG Mr CHENG Ki-kin Dr Anna TANG, BBS, MH Ms Jacqueline CHUNG Dr Jeffrey PONG 1 23 DCMIN Representatives of Core Government Departments Ms Angela LUK, JP District Officer (Wan Chai), Home Affairs Department Ms Renie LAI Assistant District Officer (Wan Chai), Home Affairs Department Ms Daphne CHAN Senior Liaison Officer (Community Affairs), Home Affairs Department Mr CHAN Chung-chi District Environmental Hygiene Superintendent (Wan Chai), Food and Environmental Hygiene Department Mr Nelson CHENG District Commander (Wan Chai), Hong Kong Police Force Ms Dorothy NIEH Police Community Relation Officer (Wan Chai District), Hong Kong Police Force Mr FUNG Ching-kwong Assistant District Social Welfare Officer (Eastern/Wan Chai)1, Social Welfare Department Mr Nelson CHAN Chief Transport Officer/Hong Kong, Transport Department Mr Franklin TSE Senior Engineer 5 (HK Island Div 2), Civil Engineering and Development Department Mr Simon LIU Chief Leisure Manager (Hong Kong East), Leisure and Cultural Services Department Ms Brenda YEUNG District Leisure Manager (Wan Chai), Leisure and -

Hong Kong Final Report

Urban Displacement Project Hong Kong Final Report Meg Heisler, Colleen Monahan, Luke Zhang, and Yuquan Zhou Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Research Questions 5 Outline 5 Key Findings 6 Final Thoughts 7 Introduction 8 Research Questions 8 Outline 8 Background 10 Figure 1: Map of Hong Kong 10 Figure 2: Birthplaces of Hong Kong residents, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 11 Land Governance and Taxation 11 Economic Conditions and Entrenched Inequality 12 Figure 3: Median monthly domestic household income at LSBG level, 2016 13 Figure 4: Median rent to income ratio at LSBG level, 2016 13 Planning Agencies 14 Housing Policy, Types, and Conditions 15 Figure 5: Occupied quarters by type, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Figure 6: Domestic households by housing tenure, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Public Housing 17 Figure 7: Change in public rental housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 18 Private Housing 18 Figure 8: Change in private housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 19 Informal Housing 19 Figure 9: Rooftop housing, subdivided housing and cage housing in Hong Kong 20 The Gentrification Debate 20 Methodology 22 Urban Displacement Project: Hong Kong | 1 Quantitative Analysis 22 Data Sources 22 Table 1: List of Data Sources 22 Typologies 23 Table 2: Typologies, 2001-2016 24 Sensitivity Analysis 24 Figures 10 and 11: 75% and 25% Criteria Thresholds vs. 70% and 30% Thresholds 25 Interviews 25 Quantitative Findings 26 Figure 12: Population change at TPU level, 2001-2016 26 Figure 13: Change in low-income households at TPU Level, 2001-2016 27 Typologies 27 Figure 14: Map of Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Table 3: Table of Draft Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Typology Limitations 29 Interview Findings 30 The Gentrification Debate 30 Land Scarcity 31 Figures 15 and 16: Google Earth Images of Wan Chai, Dec. -

Town Planning Appeal No. 18 of 2005

IN THE TOWN PLANNING APPEAL BOARD Town Planning Appeal No. 18 of 2005 BETWEEN WAN SHUET CHUN (溫雪珍) 1st Appellant CHAN WAI HING (陳惠興) 2nd Appellant LEE YUK PING (李玉萍) 3rd Appellant LAU WING YEE (劉穎而) 4th Appellant TAM KIN YEUNG (譚建陽) 5th Appellant YEUNG YUET YING (JANET) 6th Appellant CHAN TAK MING & TAM KWAN HING 7th Appellant TSANG SIM (曾嬋) 8th Appellant NG MAN SHING (伍萬成) 9th Appellant FOK LAI CHING 10th Appellant FREE WAVE CO. LTD. 11th Appellant RACO INVESTMENT LTD (偉恆昌) 12th Appellant WEI HUA DEVELOPMENT LTD (偉華發展) 13th Appellant IP TAK HING 14th Appellant CHAN NGO & YIP PUI (陳娥 & 葉培) 15th Appellant CHING KANG HOI (程鏡海) 16th Appellant TSE SAI KUI (謝世區) 17th Appellant LEE KIT MAN (李潔雯) 18th Appellant SUEN CHING TONG (孫政堂) 19th Appellant and THE TOWN PLANNING BOARD Respondent Appeal Board : Mr. Patrick FUNG Pak-tung, SC (Chairman) Mr. KAM Man-kit (Member) Ms. Helen KWAN Po-jen (Member) Ms. Ivy TONG May-hing (Member) Mr. WONG Chun-wai (Member) In Attendance : Miss Christine PANG (Secretary) Representation : Mr. TO Lap-kee, Madam FOK Lai-ching & Others as representatives of the Appellants Mr. Simon LAM (instructed by the Department of Justice) for the Respondent Date of Hearing: 1st, 3rd, 14th November & 6th December 2006 Date of Decision: 12th April 2007 D E C I S I O N - 2 - The Constitution of the Appeal Board 1. Before we go into the substance of this Appeal, we need to deal with the constitution of the Appeal Board. 2. As indicated by the formal part of this Decision above, this Appeal was originally heard by five members of the Appeal Board, including Mr. -

Page 1 of Annex a Development Proposals/Cases Related To

Page 1 of Annex A Development Proposals/Cases Related to Preservation of Historic Buildings (Position as at 30 November 2010) Hong Kong Island Development Project/Case Built Heritage At The Site Background & Current Progress 1. Revitalization of the Former Central The CPS Compound comprising the Central Following extensive consultation with the public and Police Station Compound (CPS Police Station, the Central Magistracy and the the local arts and cultural sector, a revised design for Compound) Victoria Prison has been declared a monument the project was announced on 11 October 2010. since 1995. There are a number of Victoria-style buildings within the site. A Conservation Under the revised design, the CPS Compound will be Management Plan (CMP) was presented to the revitalised as a centre for heritage, art and leisure, Board at its meeting on 26 November 2008. complementing the organic development of the neighbouring area as a contemporary arts zone. All 15 historic buildings in the Compound will be preserved. Two new buildings of a modest scale will be constructed, namely the Old Bailey Wing to house gallery space and the Arbuthnot Wing to house a multi-purpose venue as well as central plant. In response to the public views received, the height and the bulk of the proposed new structures have been substantially reduced and the F Hall will be preserved. Accessibility to the compound and connectivity within the compound has been enhanced under the revised design. 2. Re-provisioning of David Trench The Old Upper Levels Police Station, commonly HIA including a CMP has been conducted for the Rehabilitation Centre to the Old known as “No. -

Views and Suggestions Received from the Public on the Review of Built Heritage Conservation Policy

LC Paper No. CB(2)1599/06-07(01) For discussion on 20 April 2007 Legislative Council Panel on Home Affairs Views and Suggestions Received from the Public on the Review of Built Heritage Conservation Policy Purpose This paper sets out a summary of the public views and suggestions gathered on the review of built heritage conservation policy from 2004 to early 2007. Background 2. At the meeting of the Legislative Council Panel on Home Affairs on 9 March 2007, Members proposed that the Administration should provide a summary of major views, concerns and suggestions received since the 2004 public consultation exercise. The summary should include views relating to legislative, funding or administrative proposals, as well as key issues over which consensus or divided views had been expressed by the public. Summary of Public Views 3. Against the above background, a summary of views, concerns, and suggestions covering the following main areas regarding built heritage conservation is at Annex – (a) What do we conserve; (b) How do we conserve; (c) How much, and who should pay; and (d) Suggestions on legislative and institutional measures. Page 1 4. The public views we have received so far point to the need for substantial improvements to the current policy and practices on built heritage conservation. There was general support for – (a) Adopting a holistic approach to heritage conservation; (b) Revising the current assessment and selection process of built heritage; (c) Expanding the scope of protection from individual buildings to “streets” and -

A Relational Geography of Heritage in Post-1997 Hong Kong

A RELATIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF HERITAGE IN POST-1997 HONG KONG by Lachlan Barber B.A., The University of King’s College, 2004 M.A., The University of British Columbia, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2014 © Lachlan Barber, 2014 Abstract The central question of this dissertation is: what can Hong Kong teach us about the geography of heritage? The study considers the discursive transformation of cultural heritage as a feature of Hong Kong’s transition since the 1997 retrocession to Chinese sovereignty. Specifically, it traces the contradictory growth of interest in heritage as an urban amenity on the part of the government, and its simultaneous framing as a socio-political critique of neoliberal governance on the part of actors in civil society. The study analyses these dynamics from a perspective attentive to the relationships – forged through various forms of mobility and comparison – between Hong Kong and other places including mainland China, Great Britain, and urban competitors. The project relies on data gathered through English-language research conducted over a period of two and a half years. Sixty in-depth interviews were carried out with experts, activists, professionals and politicians in Hong Kong. Extensive surveys of government documents, the print and online media, and archival materials were undertaken. Other methods employed include site visits and participant observation. The methodology was oriented around the analysis of processes of heritage policy and contestation over a number of sites in Central, Hong Kong and surrounding districts where contradictory visions of the meaning of heritage have played out materially. -

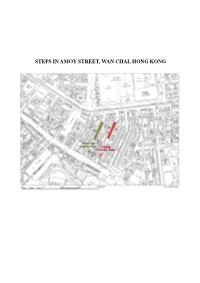

Steps in Amoy Street, Wan Chai, Hong Kong

STEPS IN AMOY STREET, WAN CHAI, HONG KONG Contents 1. Background of the Study 2. Research on the Study Area 2.1 Early History of the Study Area 2.2 Amoy Street: Origins and Early Development 3. The Steps in Amoy Street: Preliminary Findings 3.1 Site Observations 3.2 Land Records 4. Findings of Ground Investigations at No. 186 Queen’s Road East 5. Comparison with Swatow Street 6. Conclusions 7. Bibliography 8. Chronology of Events 9. Plates 1 Pottinger’s Map (1842) 2 Gordon’s Map (1843) 3 Lt Collinson’s Ordnance Survey (1845) 4 Plan of Marine Lot 40 (1859) 5 Plan of Marine Lot 40 (1866) 6 Plan of Marine Lot 40 (1889) 7 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Lanes (1901) 8 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Streets (1921) 9 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Streets (1936) 10 Widening of Amoy Street (1949) 11 Surrender of Sec. A of I.L. 4333 (1949) 12 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Streets (1959) 13 Plan of Swatow Street (1938) 14 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Streets (1963) 15 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Streets (1967) 1 1. Background of the Study 1.1 The Urban Renewal Authority (URA) will redevelop the site of Lee Tung Street and McGregor Street for a comprehensive commercial and residential development with GIC facilities and public open space. Shophouses at 186-190 Queen’s Road East (Grade II) will be conserved for adaptive re-use. The Town Planning Board (TPB) at its meeting on 22 May 2007 approved the Master Layout Plan submitted by URA with conditions including the submission of a conservation plan for the shophouses to be preserved within the site to the satisfaction of the Director of Leisure and Cultural Services or of the TPB. -

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T. Tsang Tai Uk (曾大屋, literally the Big Mansion of the Tsang Family) is also Historical called Shan Ha Wai (山廈圍, literally, Walled Village at the Foothill). Its Interest construction was started in 1847 and completed in 1867. Measuring 45 metres by 137 metres, it was built by Tsang Koon-man (曾貫萬, 1808-1894), nicknamed Tsang Sam-li (曾三利), who was a Hakka (客家) originated from Wuhua (五華) of Guangdong (廣東) province which was famous for producing masons. He came to Hong Kong from Wuhua working as a quarryman at the age of 16 in Cha Kwo Ling (茶果嶺) and Shaukiwan (筲箕灣). He set up his quarry business in Shaukiwan having his shop called Sam Lee Quarry (三利石行). Due to the large demand for building stone when Hong Kong was developed as a city since it became a ceded territory of Britain in 1841, he made huge profit. He bought land in Sha Tin from the Tsangs and built the village. The completed village accommodated around 100 residential units for his family and descendents. It was a shelter of some 500 refugees during the Second World War and the name of Tsang Tai Uk has since been adopted. The sizable and huge fortified village is a typical Hakka three-hall-four-row Architectural (三堂四横) walled village. It is in a Qing (清) vernacular design having a Merit symmetrical layout with the main entrance, entrance hall, middle hall and main hall at the central axis. Two other entrances are to either side of the front wall. -

Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” the HK UDA

Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” The HK UDA •The Hong Kong Urban Design Alliance (HK UDA) was established in 2001 •Objective - Improving the quality of urban life in Hong Kong by fostering greater awareness and promoting higher standards of urban design •An Alliance of: •HKIP; and •HKIA. •With participation from the HKILA, AIA-HK (UDC) and the PIA (HK) •The UDA promotes a high standard of urban design, the art of making places for people – the public realm – and improving the quality of urban life Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” Aerial View of Entire Central Waterfront Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” Previous Central Reclamation Plan Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” Aerial Photo of Harbour Reclamations Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” 1998 Draft Central Extension OZP Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” Aerial View of Harbour with Lines of Potential Reclamation Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” Government’s Current Proposal • The UDA Submitted specific comments on Government’s Consultation Digest •The UDA Disagrees with many of the claims made by Government in this Document under several headings • For comparison sake, the same criteria set out in the Government’s document has been used for our proposal •The UDA have commented on these and made a comparison with our own proposal Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” Designing Hong Kong’s Central Waterfront of Hong Kong International Urban Planning & Design Competition 1st Prize – Amphibian Carpet nd 2 Prize – Hong Kong Waterfront 3rd Prize – Emerald Necklace 4th Prize - Sky for Dragon, Earth for People Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” Central Harbour -“The Happening Place” Central Harbour - “The Happening A. -

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2021-22 Reply Serial No

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2021-22 Reply Serial No. DEVB(W)076 CONTROLLING OFFICER’S REPLY (Question Serial No. 1968) Head: (194) Water Supplies Department Subhead (No. & title): (000) Operational Expenses Programme: (1) Water Supply: Planning and Distribution Controlling Officer: Director of Water Supplies (LO Kwok-wah) Director of Bureau: Secretary for Development Question: Regarding water consumption in the past 3 years in Hong Kong, would the Government inform this Committee of: 1. the water consumption per year in Hong Kong and the source of drinking water supply; 2. the number and results of tests on drinking water of residential units each year; 3. the ratio of using fresh water for flushing; whether it will be lowered in the coming 10 years; if yes, of the details; 4. the estimated number of households living in village houses in rural areas that will convert to salt water for flushing in the coming year (broken down by District Council district); 5. the respective number of reports of fresh water main bursts and salt water main bursts in each district each year; 6. the total quantity of drinking water wasted each year; and 7. the progress of the Replacement and Rehabilitation Programme for water mains? Asked by: Hon CHAN Hak-kan (LegCo internal reference no.: 87) Reply: 1. The sources of fresh water supply in Hong Kong include rainwater collected from local catchments of impounding reservoirs and Dongjiang water imported from Guangdong Province. The fresh water consumptions (including consumption of fresh water for flushing) in Hong Kong in the past 3 years are tabulated below: Year Fresh water consumption (million cubic metres) 2018 1 013 2019 996 2020 1 027 2. -

Hopewell Focuses on Sustainability

HOPEWELL FOCUSES ON SUSTAINABILITY OUR HISTORY GUIDES OUR FUTURE Contents About This Report 1 Our People 23 Managing Director’s Message 2 Customers and Communities 27 Our Business 3 Procurement and Supply Chain 34 Our Sustainability Vision and Focus 6 Progress of Actions and Sustainability Targets for 2012/13 36 Stakeholder Engagement 9 Economic Performance Table 39 Case Study 1: Hopewell 40th Anniversary 13 Environmental Performance Tables 40 Environmental Performance 15 Social Performance Table 43 Case Study 2: Green Transportation 20 Verification Statements 45 Case Study 3: Hopewell New Town: GRI Index Table 47 Building a Green Community 22 Glossary 51 ABOUT THIS REPORT Hopewell Holdings Limited (“HHL” and together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”) published its first Sustainability Report in 2011. This second annual Sustainability Report (“Report”) demonstrates our continuing commitment to transparency and accountability to our stakeholders. A summary of this Report has been incorporated into our Annual Report 2011/12 and the full version is available for download at http://www.hopewellholdings.com/en-US/corporate-sustainability/sustainability-report. Scope of the Report This Report presents a group-wide approach to sustainability and our performance in the economic, environmental and social aspects of our business during our 2011/12 financial year, i.e. from 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. It covers the activities of HHL, its key subsidiaries and joint-venture operations central to our core business activities in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Our core operations involve four business sectors: property investment and development, hospitality, highways and energy. How we Report The materiality of the topics covered in this Report was determined through stakeholder dialogue – both structured and informal. -

Administration's Paper on Work of the Urban Renewal Authority

LC Paper No. CB(1) 1006/20 -21(03) For discussion on 22 June 2021 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL ON DEVELOPMENT Work of the Urban Renewal Authority PURPOSE In accordance with established practice, the Urban Renewal Authority (“URA”) reports to the Legislative Council Panel on Development annually the progress of its work and its future work plan. This paper attaches the report submitted by URA in respect of the progress of its work in 2020-21 and its Business Plan for 2021-22. BACKGROUND 2. URA was established in May 2001 to undertake urban renewal in accordance with the Urban Renewal Authority Ordinance (Cap. 563) (“URAO”). The purposes of URA and membership of URA Board are at Annex A. 3. The URAO provides for the formulation of an Urban Renewal Strategy (“URS”), the implementation of which should be undertaken by URA and other stakeholders / participants. Since the promulgation of the new URS in February 2011 (“the 2011 URS”), URA has launched all the new initiatives set out in the 2011 URS and adopted “Redevelopment” and “Rehabilitation” as its two core businesses. WORK OF URA IN 2020-21 AND BUSINESS PLAN FOR 2021-22 4. The report submitted by URA on the progress of its work in implementing the 2011 URS and its work plan for the following financial year is at Annex B. - 2 - ADVICE SOUGHT 5. Members are invited to note the work of URA in 2020-21 and its future work plan. Development Bureau June 2021 Annex A Urban Renewal Authority (URA) According to Section 5 of the Urban Renewal Authority Ordinance (Cap.