Civilitas 政學 Editor-In-Chief IP Ka Wing Helen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Translation) Minutes of the 23 Meeting of the 4 Wan Chai District

(Translation) Minutes of the 23rd Meeting of the 4th Wan Chai District Council Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Date: 7 July 2015 (Tuesday) Time: 2:30 p.m. Venue: District Council Conference Room, Wan Chai District Office, 21/F Southorn Centre, 130 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, H.K. Present Chairperson Mr SUEN Kai-cheong, SBS, MH, JP Vice-Chairperson Mr Stephen NG, BBS, MH, JP Members Ms Pamela PECK Ms Yolanda NG, MH Ms Kenny LEE Ms Peggy LEE Mr Ivan WONG, MH Mr David WONG Mr CHENG Ki-kin Dr Anna TANG, BBS, MH Ms Jacqueline CHUNG Dr Jeffrey PONG 1 23 DCMIN Representatives of Core Government Departments Ms Angela LUK, JP District Officer (Wan Chai), Home Affairs Department Ms Renie LAI Assistant District Officer (Wan Chai), Home Affairs Department Ms Daphne CHAN Senior Liaison Officer (Community Affairs), Home Affairs Department Mr CHAN Chung-chi District Environmental Hygiene Superintendent (Wan Chai), Food and Environmental Hygiene Department Mr Nelson CHENG District Commander (Wan Chai), Hong Kong Police Force Ms Dorothy NIEH Police Community Relation Officer (Wan Chai District), Hong Kong Police Force Mr FUNG Ching-kwong Assistant District Social Welfare Officer (Eastern/Wan Chai)1, Social Welfare Department Mr Nelson CHAN Chief Transport Officer/Hong Kong, Transport Department Mr Franklin TSE Senior Engineer 5 (HK Island Div 2), Civil Engineering and Development Department Mr Simon LIU Chief Leisure Manager (Hong Kong East), Leisure and Cultural Services Department Ms Brenda YEUNG District Leisure Manager (Wan Chai), Leisure and -

Hong Kong Final Report

Urban Displacement Project Hong Kong Final Report Meg Heisler, Colleen Monahan, Luke Zhang, and Yuquan Zhou Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Research Questions 5 Outline 5 Key Findings 6 Final Thoughts 7 Introduction 8 Research Questions 8 Outline 8 Background 10 Figure 1: Map of Hong Kong 10 Figure 2: Birthplaces of Hong Kong residents, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 11 Land Governance and Taxation 11 Economic Conditions and Entrenched Inequality 12 Figure 3: Median monthly domestic household income at LSBG level, 2016 13 Figure 4: Median rent to income ratio at LSBG level, 2016 13 Planning Agencies 14 Housing Policy, Types, and Conditions 15 Figure 5: Occupied quarters by type, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Figure 6: Domestic households by housing tenure, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Public Housing 17 Figure 7: Change in public rental housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 18 Private Housing 18 Figure 8: Change in private housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 19 Informal Housing 19 Figure 9: Rooftop housing, subdivided housing and cage housing in Hong Kong 20 The Gentrification Debate 20 Methodology 22 Urban Displacement Project: Hong Kong | 1 Quantitative Analysis 22 Data Sources 22 Table 1: List of Data Sources 22 Typologies 23 Table 2: Typologies, 2001-2016 24 Sensitivity Analysis 24 Figures 10 and 11: 75% and 25% Criteria Thresholds vs. 70% and 30% Thresholds 25 Interviews 25 Quantitative Findings 26 Figure 12: Population change at TPU level, 2001-2016 26 Figure 13: Change in low-income households at TPU Level, 2001-2016 27 Typologies 27 Figure 14: Map of Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Table 3: Table of Draft Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Typology Limitations 29 Interview Findings 30 The Gentrification Debate 30 Land Scarcity 31 Figures 15 and 16: Google Earth Images of Wan Chai, Dec. -

Grand Bauhinia Medal (GBM)

Appendix Grand Bauhinia Medal (GBM) The Honourable Chief Justice CHEUNG Kui-nung, Andrew Chief Justice CHEUNG is awarded GBM in recognition of his dedicated and distinguished public service to the Judiciary and the Hong Kong community, as well as his tremendous contribution to upholding the rule of law. With his outstanding ability, leadership and experience in the operation of the judicial system, he has made significant contribution to leading the Judiciary to move with the times, adjudicating cases in accordance with the law, safeguarding the interests of the Hong Kong community, and maintaining efficient operation of courts and tribunals at all levels. He has also made exemplary efforts in commanding public confidence in the judicial system of Hong Kong. The Honourable CHENG Yeuk-wah, Teresa, GBS, SC, JP Ms CHENG is awarded GBM in recognition of her dedicated and distinguished public service to the Government and the Hong Kong community, particularly in her capacity as the Secretary for Justice since 2018. With her outstanding ability and strong commitment to Hong Kong’s legal profession, Ms CHENG has led the Department of Justice in performing its various functions and provided comprehensive legal advice to the Chief Executive and the Government. She has also made significant contribution to upholding the rule of law, ensuring a fair and effective administration of justice and protecting public interest, as well as promoting the development of Hong Kong as a centre of arbitration services worldwide and consolidating Hong Kong's status as an international legal hub for dispute resolution services. The Honourable CHOW Chung-kong, GBS, JP Over the years, Mr CHOW has served the community with a distinguished record of public service. -

Saving Hong Kong's Cultural Heritage

SAVING HONG KONG’S CULTURAL HERITAGE BY CECILIA CHU AND KYLIE UEBEGANG February 2002 Civic Exchange Room 601, Hoseinee House, 69 Wyndham Street, Central Tel: 2893-0213 Fax: 3105-9713 www.civic-exchange.org TABLE OF CONTENTS. page n.o ABBREVIATIONS AND TERMINOLOGY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ………………………………………………………..….. 3 INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………….……. 4 PART I: CONSERVING HONG KONG 1. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK…………………………………… 6 1.1 WHY CONSERVE? …………………………………………….. 6 1.2 HERITAGE CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT .…………..…. 6 1.3 CHALLENGES OF HERITAGE CONSERVATION ……………..….. 7 1.4 AN OVERVIEW OF HERITAGE CONSERVATION IN HONG KONG… 7 2. PRACTICAL FRAMEWORK 2.1 EXISTING HERITAGE CONSERVATION FRAMEWORK …………. 9 • LEGAL FRAMEWORK ……………………………………..…….10 • ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK …..………………….. 13 • TOURISM BODIES ……………………………..……… 14 • INTERNATIONAL BODIES …………………….………. 15 • PRIVATE SECTOR PARTICIPATION .………….……….. 17 2.2 CONSTRAINTS WITH THE EXISTING HERITAGE CONSERVATION FRAMEWORK • OVERALL ……………………………………………… 19 • LEGAL FRAMEWORK ..………………………………… 21 • ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK ………...…………….. 24 • TOURISM BODIES ….…………………………………… *27 PART II: ACHIEVING CONSERVATION 3. RECOMMENDATIONS 3.1 OVERALL ……..………………………………………………. 29 3.2 LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE .………...……...………………….. 33 4. CASE STUDIES 4.1 NGA TSIN WAI VILLAGE …….………………………………. 34 4.2 YAUMATEI DISTRICT ………………………………………... 38 CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………… 42 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ………………………………………………………………. 43 ABBREVIATIONS AAB Antiquities Advisory Board AFCD Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department -

Branch List English

Telephone Name of Branch Address Fax No. No. Central District Branch 2A Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2160 8888 2545 0950 Des Voeux Road West Branch 111-119 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 2546 1134 2549 5068 Shek Tong Tsui Branch 534 Queen's Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, Hong Kong 2819 7277 2855 0240 Happy Valley Branch 11 King Kwong Street, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 2838 6668 2573 3662 Connaught Road Central Branch 13-14 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2841 0410 2525 8756 409 Hennessy Road Branch 409-415 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2835 6118 2591 6168 Sheung Wan Branch 252 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2541 1601 2545 4896 Wan Chai (China Overseas Building) Branch 139 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2529 0866 2866 1550 Johnston Road Branch 152-158 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2574 8257 2838 4039 Gilman Street Branch 136 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2135 1123 2544 8013 Wyndham Street Branch 1-3 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong 2843 2888 2521 1339 Queen’s Road Central Branch 81-83 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong 2588 1288 2598 1081 First Street Branch 55A First Street, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong 2517 3399 2517 3366 United Centre Branch Shop 1021, United Centre, 95 Queensway, Hong Kong 2861 1889 2861 0828 Shun Tak Centre Branch Shop 225, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2291 6081 2291 6306 Causeway Bay Branch 18 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2572 4273 2573 1233 Bank of China Tower Branch 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong 2826 6888 2804 6370 Harbour Road Branch Shop 4, G/F, Causeway Centre, -

Future Working Relationship Between the Urban Renewal Authority and the Government

Future Working Relationship between the Urban Renewal Authority and the Government Purpose This paper sets out the future working relationship between the Planning, Environment and Lands Bureau (PELB) and concerned government departments, and the Urban Renewal Authority (URA). Background 2. In his 1999 Policy Address, the Chief Executive announced that a new statutory body, the URA, will be established in 2000 to implement the Government’s urban renewal strategy in the 21st century. The URA will replace the existing Land Development Corporation (LDC) and take over all the assets and liabilities of the LDC, including redevelopment projects in progress, when the URA is set up. 3. The LDC was set up in January 1988 as a statutory body to carry out urban renewal projects. A well-established working relationship between PELB, the Planning Department (PlanD) and the Lands Department (LandsD) has developed over the years to facilitate and speed up LDC’s redevelopment projects. 4. Dedicated urban renewal teams have been set up in PELB (7 posts), PlanD (21 posts) and LandsD (30 posts) to facilitate the work of the LDC and coordinate the duties and responsibilities between the concerned departments. - 2 - Future Working Relationship 5. The existing structure and working relationship will continue after the establishment of the URA. The dedicated teams will remain in PELB, PlanD and LandsD to facilitate the work of the URA. 6. The main tasks of the URA will be: (a) redevelopment of dilapidated buildings (a 20-year urban renewal programme, including 200 priority projects concentrating in 9 urban renewal target areas)(a map showing the 9 target areas is at the Annex); (b) rehabilitation of older buildings within the 9 target areas; and (c) preservation of buildings of historical, cultural or architectural interest in the 9 target areas and other urban redevelopment sites. -

The Chief Executive's 2020 Policy Address

The Chief Executive’s 2020 Policy Address Striving Ahead with Renewed Perseverance Contents Paragraph I. Foreword: Striving Ahead 1–3 II. Full Support of the Central Government 4–8 III. Upholding “One Country, Two Systems” 9–29 Staying True to Our Original Aspiration 9–10 Improving the Implementation of “One Country, Two Systems” 11–20 The Chief Executive’s Mission 11–13 Hong Kong National Security Law 14–17 National Flag, National Emblem and National Anthem 18 Oath-taking by Public Officers 19–20 Safeguarding the Rule of Law 21–24 Electoral Arrangements 25 Public Finance 26 Public Sector Reform 27–29 IV. Navigating through the Epidemic 30–35 Staying Vigilant in the Prolonged Fight against the Epidemic 30 Together, We Fight the Virus 31 Support of the Central Government 32 Adopting a Multi-pronged Approach 33–34 Sparing No Effort in Achieving “Zero Infection” 35 Paragraph V. New Impetus to the Economy 36–82 Economic Outlook 36 Development Strategy 37 The Mainland as Our Hinterland 38–40 Consolidating Hong Kong’s Status as an International Financial Centre 41–46 Maintaining Financial Stability and Striving for Development 41–42 Deepening Mutual Access between the Mainland and Hong Kong Financial Markets 43 Promoting Real Estate Investment Trusts in Hong Kong 44 Further Promoting the Development of Private Equity Funds 45 Family Office Business 46 Consolidating Hong Kong’s Status as an International Aviation Hub 47–49 Three-Runway System Development 47 Hong Kong-Zhuhai Airport Co-operation 48 Airport City 49 Developing Hong Kong into -

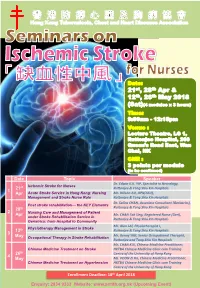

21St, 28Th Apr & 12Th, 26Th May 2018 (Sat)(4 Modules X 3 Hours)

Date: 21st, 28th Apr & 12th, 26th May 2018 (Sat)(4 modules x 3 hours) Time: 9:00am - 12:15pm Venue : Lecture Theatre, LG 1, Ruttonjee Hospital, 266 Queen’s Road East, Wan Chai, HK CNE : 3 points per module (to be confirmed) Date Topic Speaker Dr. Edwin K.K. YIP, Specialist in Neurology, Ischemic Stroke for Nurses 21st Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 1 Apr Acute Stroke Service in Hong Kong: Nursing Mr. Wilson AU, APN(ASU), Management and Stroke Nurse Role Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Dr. Selina CHAN, Associate Consultant (Geriatrics), Post stroke rehabilitation— the KEY Elements 28th Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 2 Nursing Care and Management of Patient Apr Mr. CHAN Tak Sing, Registered Nurse (Geri), under Stroke Rehabilitation Service in Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Geriatrics: from Hospital to Community Mr. Alan LAI, Physiotherapist I, Physiotherapy Management in Stroke 12th Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 3 Mr. Benny YIM, Senior Occupational Therapist, May Occupational Therapy in Stroke Rehabilitation Ruttonjee and Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Mr. CHAN KUI, Chinese Medicine Practitioner, Chinese Medicine Treatment on Stroke HKTBA Chinese Medicine Clinic cum Training 26th Centre of the University of Hong Kong 4 May Ms. POON Zi Ha, Chinese Medicine Practitioner, Chinese Medicine Treatment on Hypertension HKTBA Chinese Medicine Clinic cum Training Centre of the University of Hong Kong Enrollment Deadline: 18th April 2018 Enquiry: 2834 9333 Website: www.antitb.org.hk (Upcoming Event) Seminars on “Ischemic Stroke” for Nurses Objectives a) To strengthen, update and develop knowledge of nurses on the topic of endocrine system. b) To enhance the skills and technique in daily practice. -

Town Planning Appeal No. 18 of 2005

IN THE TOWN PLANNING APPEAL BOARD Town Planning Appeal No. 18 of 2005 BETWEEN WAN SHUET CHUN (溫雪珍) 1st Appellant CHAN WAI HING (陳惠興) 2nd Appellant LEE YUK PING (李玉萍) 3rd Appellant LAU WING YEE (劉穎而) 4th Appellant TAM KIN YEUNG (譚建陽) 5th Appellant YEUNG YUET YING (JANET) 6th Appellant CHAN TAK MING & TAM KWAN HING 7th Appellant TSANG SIM (曾嬋) 8th Appellant NG MAN SHING (伍萬成) 9th Appellant FOK LAI CHING 10th Appellant FREE WAVE CO. LTD. 11th Appellant RACO INVESTMENT LTD (偉恆昌) 12th Appellant WEI HUA DEVELOPMENT LTD (偉華發展) 13th Appellant IP TAK HING 14th Appellant CHAN NGO & YIP PUI (陳娥 & 葉培) 15th Appellant CHING KANG HOI (程鏡海) 16th Appellant TSE SAI KUI (謝世區) 17th Appellant LEE KIT MAN (李潔雯) 18th Appellant SUEN CHING TONG (孫政堂) 19th Appellant and THE TOWN PLANNING BOARD Respondent Appeal Board : Mr. Patrick FUNG Pak-tung, SC (Chairman) Mr. KAM Man-kit (Member) Ms. Helen KWAN Po-jen (Member) Ms. Ivy TONG May-hing (Member) Mr. WONG Chun-wai (Member) In Attendance : Miss Christine PANG (Secretary) Representation : Mr. TO Lap-kee, Madam FOK Lai-ching & Others as representatives of the Appellants Mr. Simon LAM (instructed by the Department of Justice) for the Respondent Date of Hearing: 1st, 3rd, 14th November & 6th December 2006 Date of Decision: 12th April 2007 D E C I S I O N - 2 - The Constitution of the Appeal Board 1. Before we go into the substance of this Appeal, we need to deal with the constitution of the Appeal Board. 2. As indicated by the formal part of this Decision above, this Appeal was originally heard by five members of the Appeal Board, including Mr. -

Members of Board and Profiles

76 MEMBERS OF BOARD AND PROFILES MEMBERS OF THE BOARD FROM RIGHT FRONT ROW Mr Victor SO Hing-woh (Chairman), Mr Edward CHOW Kwong-fai, Mr Laurence HO Hoi-ming, Dr Lawrence POON Wing-cheung BACK ROW The Honourable Alice MAK Mei-kuen, Professor the Honourable Joseph LEE Kok-long, Mrs Cecilia WONG NG Kit-wah, The Honourable WU Chi-wai, Mr Thomas CHAN Chung-ching, Mr Evan AU YANG Chi-chun, Mr Roger LUK Koon-hoo, Mr Stanley WONG Yuen-fai, Mr Michael MA Chiu-tsee (Executive Director), Mr Raymond LEE Kai-wing 77 MEMBERS OF BOARD AND PROFILES FROM LEFT FRONT ROW Ir WAI Chi-sing (Managing Director), Mr Nelson LAM Chi-yuen, Mr Timothy MA Kam-wah BACK ROW Ms Judy CHAN Ka-pui, Dr Gregg LI G. Ka-lok, Mr Michael WONG Yick-kam, Mr Laurence LI Lu-jen, Dr CHEUNG Tin-cheung, Miss Vega WONG Sau-wai, Mr Pius CHENG Kai-wah (Executive Director), Dr the Honourable Ann CHIANG Lai-wan, Professor Eddie HUI Chi-man, Mr David TANG Chi-fai 78 MEMBERS OF BOARD AND PROFILES Chairman : Mr Victor SO Hing-woh, SBS, JP Managing Director : Ir WAI Chi-sing, GBS, JP, FHKEng Executive Directors : Mr Pius CHENG Kai-wah Mr Michael MA Chiu-tsee Non-Executive Directors (non-official): Mr Evan AU YANG Chi-chun (from 1 December 2017) Ms Judy CHAN Ka-pui Dr the Honourable Ann CHIANG Lai-wan, SBS, JP Mr Edward CHOW Kwong-fai, JP Mr Laurence HO Hoi-ming Professor Eddie HUI Chi-man, MH Mr Nelson LAM Chi-yuen Professor the Honourable Joseph LEE Kok-long, SBS, JP Dr Gregg LI G. -

District Profiles 地區概覽

Table 1: Selected Characteristics of District Council Districts, 2016 Highest Second Highest Third Highest Lowest 1. Population Sha Tin District Kwun Tong District Yuen Long District Islands District 659 794 648 541 614 178 156 801 2. Proportion of population of Chinese ethnicity (%) Wong Tai Sin District North District Kwun Tong District Wan Chai District 96.6 96.2 96.1 77.9 3. Proportion of never married population aged 15 and over (%) Central and Western Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District North District District 33.7 32.4 32.2 28.1 4. Median age Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District Sha Tin District Yuen Long District 44.9 44.6 44.2 42.1 5. Proportion of population aged 15 and over having attained post-secondary Central and Western Wan Chai District Eastern District Kwai Tsing District education (%) District 49.5 49.4 38.4 25.3 6. Proportion of persons attending full-time courses in educational Tuen Mun District Sham Shui Po District Tai Po District Yuen Long District institutions in Hong Kong with place of study in same district of residence 74.5 59.2 58.0 45.3 (1) (%) 7. Labour force participation rate (%) Wan Chai District Central and Western Sai Kung District North District District 67.4 65.5 62.8 58.1 8. Median monthly income from main employment of working population Central and Western Wan Chai District Sai Kung District Kwai Tsing District excluding unpaid family workers and foreign domestic helpers (HK$) District 20,800 20,000 18,000 14,000 9. -

Wan Chai Connect Design Group Lead Consultant / Ideation / Buro Happold Multi Disciplinary Engineering / Sustainability Strategy

52 CITIES Wan Chai Connect Design Group Lead Consultant / Ideation / Buro Happold Multi Disciplinary Engineering / Sustainability Strategy Conceptual Architects Urban Design DCMSTUDIOS Architects Conceptual Master Planning Studio B Cost Management Currie and Brown Public Relations Stakeholder Engagement Executive Counsel Real Estate Advisory Knight Frank WAN CHAI Socal Economic Impact Waters Economics BuroHappold marketing and relationships director, Peter Dampier, said: “Serving as a catalyst for regeneration, we hope this sparks serious debate around the provision and ownership of quality public space. Private developers haven’t always historically worked with local communities to create functional but iconic public spaces or looked beyond the site to maximise value.” The Design Group believes that the provision of public space should be considered now in conjunction with the needs and desires of the Wan Chai community. The estimated cost of Wan Chai Connect’s social infrastructure (excluding the extension to the convention centre and new commercial tower) is HK$1.65 Billion. CONNECTS Wan Chai Connect presents a rare, visionary and unmissable opportunity to restore illed as Hong Kong’s equivalent of the New York High Line, Wan Chai Connect is a Hong Kong’s position as a leading World City. vision for the future, weaving old Wan Chai and the harbour, back together. Studio B managing director, Peter Brannan, said: “Taking inspiration from innovative projects B such as New York High Line (an abandoned railway redeveloped into a green walkway Making something out of nothing, Wan Chai Connect is a progressive idea conceptualised to deliver true world-class placemaking, a significant new public space, maximising societal and now the No.1 tourist attraction in New York), Seoul’s Seoullo (a former highway value, connecting the fragmented, and making it safe, enjoyable and smart to walk easily transformed to a sky garden) and Hong Kong Mid-Levels escalators (that has catalysed around Wan Chai.