The Fraser Canyon Encountered COLE HARRIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser River from Source to Mouth

FRASER RIVER FROM SOURCE TO MOUTH September 5, 2017 - 11 Days Fares Per Person: $3395 double/twin $4065 single $3210 triple > Please add 5% GST. Early Bookers: $160 discount on first 12 seats; $80 on next 8 > Experience Points: Earn 76 points from this tour. Redeem 76 points if you book by July 5. Includes Flight from Victoria to Kelowna St. John the Divine Church in Yale Coach transportation for 10 days Harrison Hot Springs pools 10 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes Copper Room music & dancing with Jones Boys Helicopter to the source of the Fraser River Fraser River Safari boat excursion Fraser River raft float trip (no white water) Paddlewheeler cruise from New Westminster Huble Homestead tour to the mouth of the Fraser River Farwell Canyon and pictographs Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site Cariboo Chilcotin Museum Transfer from New Westminster to Victoria Hat Creek Historic Ranch and roadhouse tour Knowledgeable tour director Hell’s Gate Airtram Luggage handling at hotels Alexandra Suspension Bridge 21 meals: 8 breakfasts, 9 lunches, 4 dinners Activity Level This is a unique tour with lots of activity and time outdoors while you experience many aspects of the Fraser River. The trip to the source of the Fraser requires getting in and out of a helicopter, and walking about ½ km in an alpine meadow at 2,000 metres altitude. On other days, you are boarding a large raft and two boats. Walks in- clude Farwell Canyon pictographs, Alexandra Bridge, and the boat dock to Kilby Store. This tour has activity ranging from somewhat rigorous to sedentary. -

Simon Fraser University Exchange / Study Abroad Fact Sheet: 2017/18

Simon Fraser University Exchange / Study Abroad Fact Sheet: 2017/18 GENERAL INFORMATION _________________________________________________ About SFU Simon Fraser University was founded 50 years ago with a mission to be a different kind of university – to bring an interdisciplinary rigour to learning, to embrace bold initiatives, and to engage deeply with communities near and far. Our vision is to be Canada’s most community-engaged research university. Today, SFU is Canada’s leading comprehensive research university and is ranked one of the top universities in the world. With campuses in British Columbia’s three largest cities – Vancouver, Burnaby and Surrey – SFU has eight faculties, delivers almost 150 programs to over 35,000 students, and boasts more than 130,000 alumni in 130 countries around the world. SFU is currently ranked as Canada’s top comprehensive university (Macleans 2017 University Rankings). The QS 2015 rankings placed SFU second in Canada for the international diversity of its students and for research citations per faculty member. For more, see: <www.sfu.ca/sfu-fastfacts> Campus Locations Simon Fraser University’s three unique campuses, spread throughout Metropolitan Vancouver, are all within an hour of one another by public transit. Burnaby (main campus): Perched atop Burnaby Mountain, Simon Fraser University’s original Arthur Erickson-designed campus now includes more than three dozen academic buildings and is flanked by UniverCity, a flourishing sustainable residential community. Surrey: A vibrant community hub located in the heart of one of Canada’s fastest-growing cities. Vancouver: Described by local media as the “intellectual heart of the city”, SFU’s Vancouver Campus transformed the landscape of urban education in downtown Vancouver. -

Francophone Historical Context Framework PDF

Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Canot du nord on the Fraser River. (www.dchp.ca); Fort Victoria c.1860. (City of Victoria); Fort St. James National Historic Site. (pc.gc.ca); Troupe de danse traditionnelle Les Cornouillers. (www. ffcb.ca) September 2019 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Table of Contents Historical Context Thematic Framework . 3 Theme 1: Early Francophone Presence in British Columbia 7 Theme 2: Francophone Communities in B.C. 14 Theme 3: Contributing to B.C.’s Economy . 21 Theme 4: Francophones and Governance in B.C. 29 Theme 5: Francophone History, Language and Community 36 Theme 6: Embracing Francophone Culture . 43 In Closing . 49 Sources . 50 2 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework - cb.com) - Simon Fraser et ses Voya ses et Fraser Simon (tourisme geurs. Historical contexts: Francophone Historic Places • Identify and explain the major themes, factors and processes Historical Context Thematic Framework that have influenced the history of an area, community or Introduction culture British Columbia is home to the fourth largest Francophone community • Provide a framework to in Canada, with approximately 70,000 Francophones with French as investigate and identify historic their first language. This includes places of origin such as France, places Québec, many African countries, Belgium, Switzerland, and many others, along with 300,000 Francophiles for whom French is not their 1 first language. The Francophone community of B.C. is culturally diverse and is more or less evenly spread across the province. Both Francophone and French immersion school programs are extremely popular, yet another indicator of the vitality of the language and culture on the Canadian 2 West Coast. -

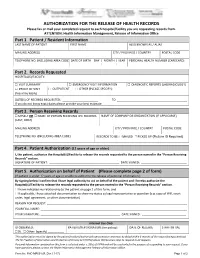

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. -

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867”

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867” The format would include a 45 minute talk on the subject with Power Point illustrations, followed by a 15 minute question and answer period. Sunday, November 19, 1:30 pm - The First Nations – First of all, I will outline the geographical setting and then examine the culture of the Plateau Native People both pre-horse and post-horse, with particular attention to the Okanagans. The lecture will look at the subsistence culture of the Plateau First Nations, both the Salish and Sahaptan language groups and the changes that the coming of the horse brought about. I will look at their annual cycle, material culture and inter-tribal trade routes with a focus on the Okanagan Valley trail that connected the Columbia and Fraser River drainage systems. Saturday, November 25, 1:30 pm - The Fur Traders from 1811 to 1847– Beginning with the first contact with white traders such as David Thompson of the North West Company and David Stuart of the Pacific Fur Company, I will look at the routes followed and the trading posts established, particularly in the Okanagan Valley and its vicinity. The brigade trail, which ran through the Okanagan Valley from Fort Okanagan to Fort Kamloops and beyond, was the major transportation route in the Interior. I will also examine the relationship between the traders and the First Nations and the inevitable tensions of this “clash of cultures.” Sunday, December 3, 1:30 pm - The Miners’ Brigades and the Traders from 1858 to 1866 – Beginning in early 1858, there was a rush of miners to the Lower Fraser River, mostly though Victoria and Fort Langley. -

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon Brian Pegg* Introduction ritish Columbia was created as a political entity because of the events of 1858, when the entry of large numbers of prospectors during the Fraser River gold rush led to a short but vicious war Bwith the Nlaka’pamux inhabitants of the Fraser Canyon. Due to this large influx of outsiders, most of whom were American, the British Parliament acted to establish the mainland colony of British Columbia on 2 August 1858.1 The cultural landscape of the Fraser Canyon underwent extremely significant changes between 1858 and the end of the nineteenth century. Construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road and the Canadian Pacific Railway, the establishment of non-Indigenous communities at Boston Bar and North Bend, and the creation of the reserve system took place in the Fraser Canyon where, prior to 1858, Nlaka’pamux people held largely undisputed military, economic, legal, and political power. Before 1858, the most significant relationship Nlaka’pamux people had with outsiders was with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which had forts at Kamloops, Langley, Hope, and Yale.2 Figure 1 shows critical locations for the events of 1858 and immediately afterwards. In 1858, most of the miners were American, with many having a military or paramilitary background, and they quickly entered into hostilities with the Nlaka’pamux. The Fraser Canyon War initially conformed to the pattern of many other “Indian Wars” within the expanding United States (including those in California, from whence many of the Fraser Canyon miners hailed), with miners approaching Indigenous inhabitants * The many individuals who have contributed to this work are too numerous to list. -

Recent Research Directions at Keatley Creek (Eeri 7) and Secret Societies in the Pacific Northwest Jesse Morin

Recent Research Directions at Keatley Creek (EeRI 7) and Secret Societies in the Pacific Northwest Jesse Morin Keatley Creek (EeRl 7) is a prehistoric large pithouse village site on the Fraser River north of Lillooet, and it had an estimated population of 1200-1500 at its zenith, with the Classic Lillooet occupation (2,300-1, 100 BP ), although the extent and development of this and other large communities is currently much debated (Hayden 2005, Prentiss et al2005, Kuijt and Prentiss 2004) (Figures 2 and 3). It has been a focus of considerable archaeologi cal investigation, nearly continuously from 1985 to present, and provides almost certainly the largest body of comparative data on household variability (especially living floors) from a single site in the Pacific Northwest (with 7 completely and 15 partially excavated pithouses of all sizes and primarily of Plateau, Kamloops, and Protohistoric Horizons) (Hayden 2000a and 2000b, 2004). It is probably not reasonable to assume all 120 of the housepits at Keatley Creek are the collapsed remains of domestic winter pithouses. We suggest that recent excavations at the peripheries of the site have revealed two sets structures and features that are very distinctive from the domestic housepits that dominate the core of the site. We suggest that the most appropriate cultural model to explain this patterning is that these locations represent two secret society compounds associated with the-site that span Plateau, Kamloops and Protohistoric occupations. Above (Figure 1): Ornaments recovered from ST 106. Includes examples of cervid tooth pendant (one of three recovered from the site), and bird bone beads (three of seven recovered from the site) (Photo by Keith Gavac). -

The Stō:Ló Is a River of Knowledge, Halq'eméylem Is a River of Stories

Walking Backwards into the Future with Our Stories: The Stō:ló is a River of Knowledge, Halq’eméylem is a River of Stories by lolehawk Laura Buker M.A. (Education), Simon Fraser University, 1980 B.Ed., University of British Columbia, 1975 Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Curriculum Theory & Implementation Program Faculty of Education © lolehawk Laura Buker Simon Fraser University Summer 2011 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for "Fair Dealing." Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Laura Buker Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: Walking Backwards Into the Future With Our Stories: The St6:lo is a River of Knowledge, Haq'emeylem is a River of Stories Examining Committee: Chair: Robin Brayne, Adjunct Professor Allan MacKinnon, Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Vicki Kelly, Assistant Professor Committee Member Elizabeth Phillips, Elder, St6:lo Nation Committee Member Heesoon Bai, Associate Professor Internal/External Examiner Jan Hare, University of British Columbia External Examiner Date Defended/Approved: ii Partial Copyright Licence Abstract Storytelling is the original form of education for the indigenous families along the Fraser River. These stories have informed ecological, linguistic and cultural knowledge for thousands of years. This story begins in the time of the oldest inhabitants of the Fraser Valley along the St ó:lō where the river and the indigenous peopleevolutionary share changethe same and name: transformation Stó:lō, People that of is the personal River. -

Thank YOLI! |~He Riistoric Fort

ou Parks Thank Y ror visiting our f)'\te.\ Pares Welcome to.. Our^tory. Canada Canada "Long ago, they never go by thermometer; they just go by animals. That's what they used to do. The beavers come out in the spring; this is when they come out. Sometimes, if they were seen to open their dams wide, it would mean that it would be a wet summer. But if they don't open their "ort ifjt. James dams, and the beaver fixes the dam right away, it meant that it would be a dry summer. Things like that, the old people watched out for. And in the late fall, if the beaver gathered its food National Jl i s t o r i c early, it meant a cold winter ahead or a long winter." ^ite of (panada Nak 'azdli Elder, Betsy Leon from "Nak'azdli Elders Speak" Long before Alexander Mackenzie came west of the Rocky Mountains in search of a navigable route to the Pacific Ocean, the Nak'azdli had their home here. Part of the Dakelh or Carrier people, the Nak'azdli nation depended mainly on the salmon for sustenance over the long winters. It was in their territory that Simon Fraser built the first trading post, Stuart Lake Outpost, in 1806. The post formed an important part of the North West Company's expansion west of the Rocky Mountains. Simon Fraser, John Stuart and those that accompanied them, found this area rich in all kinds of fur-bearing ani mals. Once established, the post became an important trading place for the Dakelh. -

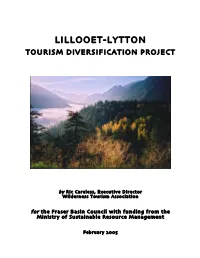

Lillooet-Lytton Tourism Diversification Project

LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT by Ric Careless, Executive Director Wilderness Tourism Association for the Fraser Basin Council with funding from the Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management February 2005 LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT by Ric Careless, Executive Director Wilderness Tourism Association for the Fraser Basin Council with funding from the Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management February 2005 LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM PROJECT 1. PROJECT BACKGROUND ..................................................................................4 1.1 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Terms of Reference............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Study Area Description...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Local Economic Challenges............................................................................................................................... 8 2. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF TOURISM.....................................................................9 2.1 Tourism in British Columbia............................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Nature-Based Tourism and Rural BC............................................................................................................ -

Assessing Simon Fraser's Legacy

SAMPLE UNIT In this sample unit, students undertake activities involving selected primary and Assessing Simon Fraser’s legacy secondary sources to support six critical thinking tasks—one The tasks in this unit focus on Simon Fraser’s exploration of the Fraser River in 1808. for each of the six For demonstration purposes, we have designed the activities as though the lessons foundational concepts are taught in the order in which they are presented. When using these lessons with of historical thinking. a class, you may want to select from among them or re-order them. However, when adapting these lessons, ensure that students have the tools they need to address the tasks presented to them. Historical Concept Critical Challenge Historical significance What was the most significant event in Fraser’s journey? Evidence and interpretation Based on the additional sources, propose at least five revisions to the account of Fraser’s journey to reflect your conclusion about the expedition. Continuity and change To what extent did Fraser change as a result of his experiences? To what extent did Indigenous reactions to Europeans change as a result of their experiences with Fraser? Historical perspective Why did various Indigenous peoples respond to Fraser as they did in the three identified incidents? Cause and consequence Based on their experiences with Fraser, how might Chief Whattlekainum and his people react to further visits from these “sky-people”? Ethical judgment How should Simon Fraser be remembered—as a gifted negotiator or a lucky bully? Launch the unit inquiry Introduce the Tell students that Simon Fraser was a famous Canadian explorer. -

Download Download

The Ethno-Genesis of the Mixed-Ancestry Population in New Caledonia Duane Thomson n British Columbia and elsewhere in Canada the question of which mixed-ancestry persons qualify for Métis status is a largely unresolved public policy issue. Whether this issue is eventually Idecided by legal decisions or by political accommodation, the historical background relating to British Columbia’s mixed-ancestry population is an important element in the discussion and requires detailed exploration. Historical research conducted for the Department of Justice forms the basis of this study of the ethno-genesis of the mixed-ancestry population of central British Columbia.1 To understand the parameters of this research, some background regarding the 2003 R. v. Powley decision in the Supreme Court of Canada is necessary. The Court ruled that Steve and Roddy Powley, two mixed-ancestry men from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, qualified for Métis status. They thus enjoyed a constitutionally protected right to hunt for food under s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.2 In its decision, the Court also set out the criteria that succeeding mixed-ancestry applicants must meet to similarly qualify for Métis status. One important criterion was that Métis Aboriginal rights rest in the existence of a historic, self- 1 For a summary of some of these legal and political issues, see Jean Barman and Mike Evans, “Reflections on Being, and Becoming, Métis in British Columbia,” BC Studies 161 (Spring 2009): 59-91. New Caledonia is the region chosen by Barman and Evans in their attempt to show that a Métis community developed in British Columbia.