1 Gazette Project Interview with Richard Portis Little Rock, Arkansas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS APRIL 12, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 20 BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] INSIDE Tenille Arts Overcomes Multiple Challenges En Route To An Unlikely First Top 10 Stapleton, Tenille Arts won’t be taking home any trophies from the 2019, it entered the chart dated Feb. 15, 2020, at No. 59, just Barrett 56th annual Academy of Country Music (ACM) Awards on weeks before COVID-19 threw businesses around the world Rule Charts April 18 — competitor Gabby Barrett received the new female into chaos. Shortly afterward, Reviver was out of the picture. >page 4 artist honor in advance — but Arts has already won big by Effective with the chart dated May 2, 19th & Grand — headed overcoming an extraordinary hurdle to claim a precedent- by CEO Hal Oven — was officially listed as the lone associated setting top 10 single with her first bona label. Reviver executive vp/GM Gator Mi- fide hit. chaels left to form a consultancy in April Clint Black Arts, who was named a finalist for new 2020 and tagged Arts and 19th & Grand ‘Circles’ TV female when nominations were unveiled as his initial clients. Former Reviver vp Feb. 26, moves to No. 9 on the Country Air- promotion Jim Malito likewise shifted to >page 11 play chart dated April 17 in her 61st week 19th & Grand, using the same title. Four on the list. Co-written with producer Alex of the five current 19th & Grand regionals Kline (Terri Clark, Erin Enderlin) and Alli- are also working the same territory they son Veltz Cruz (“Prayed for You”), “Some- worked at Reviver. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS NOVEMBER 9, 2020 | PAGE 1 OF 17 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Russell Dickerson ASCAP, BMI, SESAC Country Extends Streak >page 4 Winners Reflect On Their Jobs’ Value CMA Battles COVID-19 Successful country songwriters know how to embed their songs song of the year victor for co-writing the Luke Combs hit “Even >page 9 with just the right amount of repetition. Though I’m Leaving.” Old Dominion’s “One Man Band” took The performing rights organizations set the top of their 2020 the ASCAP country song trophy for three of the group’s mem- winners’ lists to repeat as the ASCAP, BMI and SESAC country bers — Trevor Rosen, Brad Tursi and Matthew Ramsey, who songwriter and publisher of the year awards all went to enti- previously earned the ASCAP songwriter-artist trophy in 2017 Christmas With ties who have pre- — plus songwriter The Oaks, LeVox, viously taken top Josh Osborne, Dan + Shay honors. A shley who adds the title >page 10 Gorley (“Catch,” to two song of the “Living”) hooked year winners he ASCAP’s song- co-wrote with Sam writer medallion Hunt: 2018 cham- Trebek Leaves Some for the eighth time, pion “Body Like a Trivia In His Wake and for the sev- Back Road” and >page 10 enth year in a row, 2015 victor “Leave when victors were the Night On.” unveiled Nov. 9. Even Ben Bur- Makin’ Tracks: Ross Copperman gess, who won Michael Ray’s (“What She Wants his first-ever BMI Tonight,” “Love award with “Whis- ‘Whiskey And Rain’ COPPERMAN GORLEY McGINN >page 14 Someone”) swiped key Glasses,” BMI’s songwriter cruised to the PRO’s title for the fourth time on Nov. -

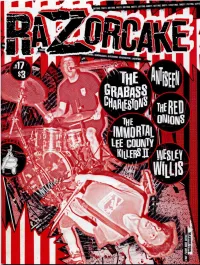

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #17 www.razorcake.com It’s strange the things you learn about yourself when you travel, I took my second trip to go to the wedding of an old friend, andI the last two trips I took taught me a lot about why I spend so Tommy. Tommy and I have been hanging out together since we much time working on this toilet topper that you’re reading right were about four years old, and we’ve been listening to punk rock now. together since before a lot of Razorcake readers were born. Tommy The first trip was the Perpetual Motion Roadshow, an came to pick me up from jail when I got arrested for being a smart independent writers touring circuit that took me through seven ass. I dragged the best man out of Tommy’s wedding after the best cities in eight days. One of those cities was Cleveland. While I was man dropped his pants at the bar. Friendships like this don’t come there, I scammed my way into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. See, along every day. they let touring bands in for free, and I knew this, so I masqueraded Before the wedding, we had the obligatory bachelor party, as the drummer for the all-girl Canadian punk band Sophomore which led to the obligatory visit to the strip bar, which led to the Level Psychology. My facial hair didn’t give me away. Nor did my obligatory bachelor on stage, drunk and dancing with strippers. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS FEBRUARY 22, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 20 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Taylor Swift’s Country Radio Seminar Addresses ‘Love Story’ Epilogue Page 4 A Virtual Pack Of Problems Country Radio Seminar may have been experienced by radio broadcasts, a larger number than any other single source, CRS Has Tigers attendees in the isolation of their own homes or offices — though when the individual digital platforms — Amazon Music, By The Tail thanks, COVID-19 — but there were plenty of elephants YouTube, Apple Music, Spotify and Pandora — are combined, Page 10 crowding the room. they account for 60% of first-time exposure, more than double The pandemic, for one, reared its head in just about every terrestrial’s turf. The difference is even more pronounced among panel discussion or showcase conversation during the conven- adults aged 18-24, who will be among country’s core listeners tion, held Feb. 16-19. The issue of country’s racial disparities — in the next decade. Brad Paisley On keyed by a series of national incidents since May and accelerated “That hurt our heart a little bit,” said KNCI Sacramento, Jeannie Seely’s Moxie by Morgan Wallen’s use of a racial slur in February — spurred Calif., PD Joey Tack, “but if we don’t hear that, how are we Page 11 one of the most dis- going to adapt?” cussed panels in the Strategies are conference’s history certainly available. as Maren Morris They include better FGL, Johnny Cash and Luke Combs educating listeners Take TPAC Country challenged country about how to find Page 11 to improve its per- their station on digi- formance. -

Template for Oral History Documents

FORT BEND COUNTY HISTORICAL COMMISSION ORAL HISTORY COMMITTEE Interviewee: Daniel L. Pavlas Interview Date: 04/29/2016 Interviewers: Jane Goodsill and Bradley Stavinoha Transcriber: Sylvia Vacek Location: Needville, Texas 17 Pages This oral history is copyrighted 2018, by the Fort Bend County Historical Commission. All Rights Reserved. For information contact: Fort Bend County Historical Commission, Attn: Chairman-Oral History Committee, 301 Jackson St., Richmond, TX, 77469. Terms and Conditions These oral histories do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the County Historical Commission or Fort Bend County. This file may not be modified or changed in any way without the express written permission of the Fort Bend County Historical Commission. This file may not be redistributed for profit. Please do not 'hot link' to this file. Please do not repost this file. Daniel L. Pavlas Page 2 04/29/2016 Transcript GOODSILL: Today is April 29, 2016; my name is Jane Goodsill, and I interviewing Dan Pavlas for the first time in Needville, Texas, for the Fort Bend County Historical Commission. Let’s start with your date of birth. PAVLAS: I was born July 3, 1930. GOODSILL: How did your family get to America? PAVLAS: My dad and mom were born here, but my grandpas from both sides came here from Czechoslovakia, I don’t remember what year. My father was Julius Pavlas and my mother was Frances Brazda. My grandpa’s last name was Felix from Czechoslovakia. He lost his wife and remarried and I don’t know who he remarried to be honest, I wasn’t here at the time [both chuckle]. -

The Musicrow Weekly Friday, November 20, 2020

November 20, 2020 The MusicRow Weekly Friday, November 20, 2020 EXCLUSIVE: Sony/ATV Nashville Acquires River House Artists Catalogue, Signs Joint Venture SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES EXCLUSIVE: Sony/ATV Nashville Acquires River House Artists Catalogue, Signs Joint Venture CRB Reveals New Faces Of Country Music Show Pictured (L-R): Sony/ATV Chairman and CEO Jon Platt, River House Artists Nominees Founder Lynn Oliver-Cline, Sony/ATV Nashville CEO Rusty Gaston. Home Team, Warner Sony/ATV Nashville has acquired the River House Artists’ catalogue of top- Chappell Music Sign charting country songs, which includes Luke Combs’ No. 1 hits “Forever Parker Welling After All,” “Beautiful Crazy,” “When It Rains It Pours,” and “Lovin’ On You.” The company also signed a joint venture with River House Artists to provide creative services to its talent. JoJamie Hahr Appointed Sr. VP, BBR Music Group Indie record label and publishing company River House Artists launched in 2016 under the leadership of veteran industry executive Lynn Oliver-Cline, ACM Lifting Lives Board Of and is home to some of today’s top country hitmakers, including Combs’ long-time friend and collaborator Ray Fulcher, well known for co-writing Directors Announced For beloved songs such as “Does To Me,” “Even Though I’m Leaving” and 2020-2021 Term “When It Rains It Pours” by Combs. CMA Awards Leaders River House Artists also represents Drew Parker, rising artist-songwriter Sarah Trahern, Robert and Sirius XM’s latest Highway Find who has co-written hits including Deaton Discuss Navigating Combs’ “1,2 Many” and “Nothing Like You,” as well as No. -

INSIDE (RCA) DAVID BOWIE on the EVE of Tonight NEW EDITION CONSTRUCTION: (EMI) Coolit Now RED ROCKERS ****** (MCA) LET's ACTIVE Cypress (IRS)

One Hallidie Plaza, Suite 725 San Francisco, California 94102 FIRST CLASS Og? U S POSTAGE PAID A ,44,1,,,ir "R48 San Francisco. GA r_ 8F Permit No 14615 W8RU/F pp['qt.)! /4, ADP 1 d rj L) PRiv AI LVULENT 0,?906 s ` t'/'`,,',0"-00`efsIeise,00',,`1`0 s s s , COUNTRY TOPFORT'? AMERICA SpecialGirl ANNE MURRAY (Capitol) E & Nobody LOGGINS Loves HALL &OATES You Me Like Touch Do Out Of SERGIOMENDES (Capitol) (RCA) Real Life (A&M) RONNIE HART. Prisoner MILSAP COREY Of TheHighway It Ain'tEnough (RCA) (EMI) Iv Ilk 1 inn) 4A1I111 ,00,r r 01..00 ;; ; THE BLACKPAGE -;,: ALBUM DIANAROSS ALTERNATIVEACTION Swept Away INSIDE (RCA) DAVID BOWIE ON THE EVE OF Tonight NEW EDITION CONSTRUCTION: (EMI) CoolIt Now RED ROCKERS ****** (MCA) LET'S ACTIVE Cypress (IRS) Issue # 1526 SAMMY'S HITTING 120 (stations) INTHIRD(weeks) 111 Can't Drive7-29173 . GEFFEN RECORDS Produced By From the Geffen Album VOA GHS 24043 TED TEMPLEMAN EL MANAGEMENT/ ED LEFFLER SAMMYH11G1111 THE GAVIN REPORT TOP FORTY EDITOR: DAVE SHOLIN POWER TRIO CERTIFIED RECORDTO WATCH MOST ADDED PRINCE A CYNDI LAUPER Let's Go Crazy HALL & OATES NEW EDITION All Through The Night (Warner Brothers) Out Of Touch Cool It Now (Portrait) -158 Adds (RCA) (MCA) LIONEL RICHIE MADONNA Penny Lover Lucky Star COREY HART Hot Week...see (Motown) -113 Adds (Sire/Warner Brothers) It Ain't Enough Analysis. CULTURE CLUB (EMI) The War Song CHICAGO (Virgin/Epic)- 113 Adds Hard Habit To Break (Full Moon /W,. .B .) "I A = Top New Airplay 2W LW TW September 28,1984 2. -

BUT WILL IT PLAY in GRAND RAPIDS? the ROLE of GATEKEEPERS in MUSIC SELECTION in 1960S TOP 40 RADIO

BUT WILL IT PLAY IN GRAND RAPIDS? THE ROLE OF GATEKEEPERS IN MUSIC SELECTION IN 1960s TOP 40 RADIO By Leonard A. O’Kelly A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Media and Information Studies - Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT BUT WILL IT PLAY IN GRAND RAPIDS? THE ROLE OF GATEKEEPERS IN MUSIC SELECTION IN 1960s TOP 40 RADIO By Leonard A. O’Kelly The decision to play (or not to play) certain songs on the radio can have financial ramifications for performers and for radio stations alike in the form of ratings and revenue. This study considers the theory of gatekeeping at the individual level, paired with industry factors such as advertising, music industry promotion, and payola to explain how radio stations determined which songs to play. An analysis of playlists from large-market Top 40 radio stations and small-market stations within the larger stations’ coverage areas from the 1960s will determine the direction of spread of song titles and the time frame for the spread of music, shedding light on how radio program directors (gatekeepers) may have been influenced in their decisions. By comparing this data with national charts, it may also be possible to determine whether or not local stations had any influence over the national trend. The role of industry trade publications such as Billboard and The Gavin Report are considered, and the rise of the broadcast consultant as a gatekeeper is explored. This study will also analyze the discrepancy in song selection with respect to race and gender as compared to national measures of popularity. -

Caroline in the Billboard Country Update!

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS APRIL 5, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 19 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] New Leaders On The Class Of ’91: A Dozen Former New Kids Three Top Charts >page 4 Have Graduated To Key Influencers CMA, MHA Staff Up Time, as Tracy Lawrence sang in a 1990s classic, marches on. and Pam Tillis; Lawrence and fellow traditionalists Aaron Tippin >page 10 The current time finds Lawrence celebrating 30 years since and Sammy Kershaw; plus pop- and folk-influenced singers his debut single — “Sticks and Stones,” which first appeared on Collin Raye, Billy Dean and Hal Ketchum. Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart dated Nov. 9, 1991 —and And it really was a class, in the sense that all the acts — ar- that anniversary arrives as ’90s country is a big deal again. riving just as Brooks had attracted the national spotlight to the Combs, Rhett, Luke Combs, Carly Pearce, Jon Pardi, Tenille Arts and Mi- genre — experienced their launch with a greater sense of pos- Bentley On ACMs chael Ray are among the modern hitmakers who count music sibility than many of their predecessors were afforded. >page 11 from that era as an “Everything was influence on their new and buzzy and work. exciting,” recalls There’s a good McBride & The Alan Jackson case to be made R i d e f r o n t m a n Is Back that Lawrence and Terry McBride. >page 11 11 other artists who “There was that debuted the same camaraderie of year, the Class of those artists, sort Makin’ Tracks: ’91, form an under- of a kinship and Caroline Jones’ appreciated founda- friendship that ‘Come In’ tion for the country was being made music that resonates from seeing these >page 16 LAWRENCE TILLISDEAN McBRIDE in 2021. -

R: This Is Kenneth Rock, and I'm Visiting Today with Mr. and Mrs

R: This is Kenneth Rock, and I'm visiting today with Mr. and Mrs. Harold Henkel. Their home, 15 Burlington, Longmont, Colorado. This is 21st of March, 1977, and we're talking about some of their experiences. So, which one of you would like to go first? Mrs. Henkel? KH: To start in, my name is Katherine Rudy (Rudi) Henkel. My mother--my dad's name was Peter Rudy, and he came from Pobotschnaja, Russia. R: Could you spell that if you have it there? KH: Pobotschnaja, Russia? R: Mm-hmm. KH: That would, let's see- R: Okay, we have it on that other-- KH: There it is, okay, the colony was, um, it's called in German [inaudible], its colony, and then Pobotschnaja is spelled P-o-b-o-t-s-c-h-n-a-j-a. That is Russian. That's when the Russian people who wouldn't let the German people name their colonies after German names anymore. My dad left Russia ahead of my mother two years, and he went to South America first. And he spent quite some time in Argentina looking for a home there, and he didn't like it, and he worked his way into America. In other words, he had to earn money, and he would go step by step. He came to the port of San Francisco. He was on the vessel the S.S. San Jose on July 24, 1913. R: That was after he was in Latin America? KH: That's right, after he was in Latin America, yes. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS MARCH 8, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 17 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] It’s Niko Moon’s Campbells’ Soup: Craig Campbell The ‘Time’ >page 4 Artist Hires Craig Campbell The Publicist Now See These: When his phone pinged several years ago, Campbell his first single, “What a Girl Will Make You Do,” on Feb. 12, re- Chesney, Midland, Entertainment Group founder Craig Campbell opened a text calling the home-life theme of his 2010 debut, “Family Man.” Clark from a number he didn’t recognize: “I’m coming home late “When people hear this song, they will know me,” the artist >page 9 from the studio. Will you pick says. “That had a lot to do with up some milk and bread on your picking this song.” way home?” For listeners within the busi- “Who is this?” he wrote back. ness, they also have to know Country Regroups “Mindy.” which Craig Campbell they’re >page 10 “Mindy who?” addressing. It’s not exactly “YOUR WIFE!” a new problem, though their That exchange was perhaps current working relationship a prelude to a new chapter in heightens the dynamic. In Grammys Tout Campbell’s professional life. the mid-2000s, Campbell the Country Women Mindy Campbell thought she new G. first found out about >page 10 was texting the artist Craig Campbell the O.G. while trying Campbell. Now the two men out for the USA Network show with the same name are work- Nashville Star. Judge Tracy Makin’ Tracks: ing together in a potentially Gershon told the artist that a Dan + Shay ‘Exist’ confusing manner: Music publicist was already working >page 14 journalists are receiving press with the same moniker.