Gas Pricing Reform in India: Implications for the Indian Gas Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PPAC's Snapshot of India's Oil & Gas Data

PPAC's Snapshot of India’s Oil & Gas data Abridged Ready Reckoner May, 2021 Petroleum Planning & Analysis Cell (Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas) As on 18.06.2021 Petroleum Planning & Analysis Cell (PPAC), an attached office of the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas (MoPNG), Government of India, collects and analyses data on the Oil and Gas sector. It disseminates many reports on the Oil & Gas sector to the various stakeholders. The data is obtained from the Public Sector companies, Government agencies as well as the Private companies. Given the ever-increasing demand for energy and transition of energy demand to renewables and Biofuels, Policy makers and Analysts need to be well informed about the updated trends in the Oil & Gas industry. The PPAC’s Snapshot of India’s Oil & Gas data (Abridged Ready Reckoner) provides a comprehensive compilation of the latest data/information in a single volume for the latest month and historical time series. The Snapshot of India’s Oil & Gas data is also published on PPAC’s website (www.ppac.gov.in) and is accessible on mobile app-PPACE. This publication is a concerted effort by all divisions of PPAC. The cooperation of the oil and gas industry is acknowledged for their timely inputs. Table of contents Table Description Page No. Highlights for the month 2-3 ECONOMIC INDICATORS 1 Selected indicators of the Indian economy 5 2 Crude oil, LNG and petroleum products at a glance; Graph 6-7 CRUDE OIL, REFINING & PRODUCTION 3 Indigenous crude oil production 9 4 Domestic oil & gas production vis-à-vis overseas -

Energy News Monitor

28 December 2018, Volume XV, Issue 29 Energy News Monitor UJJWALA YOJANA INCREASES SUBSIDY BILL Monthly Oil News Commentary: November - December 2018 India figures. Due to increased migration, some of the states like Delhi and Punjab end up having population that’s ccording to the government, nine out of 10 Indian higher than the estimates, resulting in an LPG coverage homes now use cleaner cooking gas according to A ratio of more than 100%. Overall, Goa has the highest the government. State oil companies, pushed by the oil coverage ratio of 139%. Telangana, Puducherry, Kerala ministry, have added record 100 million consumers since and Mizoram are other states with higher than 100% April 2015, expanding the active consumer base by two- coverage. Southern states together have a coverage of thirds. This has increased access to cooking gas, or LPG 99.7% while western states have 81.9%. With 74.6% to 89% of the country’s households by October end, a coverage, the eastern states are at the bottom of the pile sharp jump from 56.2% on 1 April 2015. A subsidy for although they have come a long way from their fresh LPG connection to poor families helped fuel traditionally poor access to clean energy. The worst demand. Rural areas still have untapped potential with among major states are Jharkhand (65.4%), Bihar (67%) more than half of all consumers, or about 136 million and Odisha (66.9%). In Gujarat too, the LPG coverage residing in urban areas. India has a total of 249 million ratio is 66.6% but that’s more because the state is already active customers, of which 229 million receive subsidy. -

Central Electricity Regulatory Commission, New Delhi

CENTRAL ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION, NEW DELHI Petition No. 126/MP/2017 Coram: Shri P.K. Pujari, Chairperson Shri A.K. Singhal, Member Shri A.S. Bakshi, Member Dr. M. K. Iyer, Member Date of Order: 4th May, 2018 In the matter of: Petition under Section 79(1) (c) and (d) of the Electricity Act, 2003 read with Regulations 20 and 21 of the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (Sharing of inter State transmission charges and losses) Regulations, 2010 for declaration and direction with regard to the status of the 400kV D/C Transmission Line from Indira Gandhi Super Thermal Power Station (Aravali Power Station) to Daulatabad owned, operated and maintained by Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam Limited (HVPNL). And In the matter of 1. Uttar Haryana Bijli Vitran Nigam Limited C-6, Vidyut Sadan, Sector-6, Panchkula, Haryana 2. Dakshin Haryana Bijli Vitran Nigam Limited Vidyut Sadan, Vidyut Nagar, Hissar Both represented by Haryana Power Purchase Centre A joint forum set up by Uttar Haryana Bijli Vitran Nigam and Dakshin Haryana Bijli Vitran Nigam Room No. UH 305, 2nd floor, Shakti Bhawan Sector 6 Panchkula 3. Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam Limited Shakti Bhawan Sector-6 Panchkula - Petitioners Versus 1. Power System Operation Corporation Limited, B-9, First Floor, Qutab Industrial Area, Order in Petition No. 126/MP/2017 Page 1 of 34 Katwaria Sarai, New Delhi – 110 016 2. Central Transmission Utility, Powergrid Corporation of India Limited, „Saudamini‟, Plot No. 2, Sector-29, Gurgaon-122001, Haryana 3. Aravali Power Company Pvt Limited NTPC Bhawan, Scope Complex, 7, Institutional area, Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110003 - Respondents Parties present: Shri M.G. -

(India) Pvt. Ltd. Petro Mag Petroleum Bazaar Page 1

Petroleum Bazaar.com (India) Pvt. Ltd. Issue No. :111 01, Monday, 17th March 2020 P e t r o M a g Petroleum Bazaar P a g e 1 | 50 Petroleum Bazaar.com (India) Pvt. Ltd. NEWS National News Exploration News International News Crude Oil News PRICES International Prices National Prices Retail Selling Prices STOCK PRICES Crude oil Stock Daily Share Price MCX Bhav copy DATA Import & Export – Port wise Data Industry Sales Pipeline Transfers Natural Gas Import, Sale And Production OMC-HSD Consumption OMC HSD DIRECT Consumption OMC MS DIRECT Consumption OMC-MS Consumption Import / Export Tankers Position - Petroleum Tankers Position - LPG PRODUCTION DATA Crude Oil production Natural Gas Production Refinery Production UPDATES Projects Update P e t r o M a g Petroleum Bazaar P a g e 2 | 50 Petroleum Bazaar.com (India) Pvt. Ltd. Minister Of Petroleum And Natural Gas NATIONAL NEWS Shri Dharmendra Pradhan ➢ French energy giant Total acquires 37.4% in Adani Gas for Rs 5,152 crore Secretary Dr. M M Kutty ➢ Indian refiners plan to wind down Venezuelan oil buys in April: Sources EXPLORATION NEWSNATIONAL NEWS ➢ Haldia Petrochemicals, ExxonMobil keen to set up shop in AP Additional Secretary Shri Rajiv Bansal ➢ India’s gas demand projected to rise by 66% in 5 yrs ➢ Price hike on BS-VI won't hurt consumers, will meet April deadline: IOC Joint Secretary(Refineries) Shri Sunil Kumar ➢ Hindustan Petroleum Sets up 1st EV Charging Station in Vadodara ➢ LPG penetration is 100 % in Karnataka, says IOC official Dir (Admn./Fp) Shri Mrityunjay Jha ➢ Petronet launches India’s first commercial LNG bus ➢ How falling crude prices are helping India manage inflationary, fiscal pressure Additional Secretary & Financial Adviser, ➢ 36 bottlenecks faced by 17 infra projects reviewed by Goyal-led panel Shri. -

Citizen's Charter Is to Improve the Quality of Public Services

Citizen’s Charter GAIL (India) Limited 16 Bhikaiji Cama Place, New Delhi GAIL (India) Limited – Citizen’s Charter The main objective of the Citizen's Charter is to improve the quality of public services. This is done by letting people know the mandate of the Corporation, how one can get in touch with its officials, what to expect by way of services and how to seek a remedy if something goes wrong. The Citizen’s Charter does not by itself create new legal rights, but it surely helps in enforcing existing ones. GAIL (India) Limited – Citizen’s Charter GAIL (India) Limited – Citizen’s Charter Mission To accelerate and optimize the effective and economic use of Natural Gas and its fractions for the benefit of the national economy Vision To be the leading company in Natural Gas and Beyond, with Global Focus, Committed to Customer Care, Value Creation for all Stakeholders and Environmental Responsibility. Key Elements of GAIL's Vision Ethics: We are transparent, fair and consistent in dealing with all people. We insist on honesty, integrity and trustworthiness in all our activities. Customer: We strive relentlessly to exceed the expectations of our customers, both internal and external. Our customers prefer us. People: We believe our success is driven by the commitment and excellence of our people. We attract and retain result-oriented people who are proud their work and are satisfied with nothing less than the very best in everything they do. We encourage individual initiative by creating opportunities for our people to learn and grow. We respect the individual rights and dignity of all people. -

The Challenges Facing India on Its Road to a Gas-Based Economy

The Challenges Facing India on its Road to a Gas-Based Economy Anne-Sophie Corbeau, Shahid Hasan and Swati Dsouza October 2018 Doi: 10.30573/KS--2018-DP41 The Challenges Facing India on its Road to a Gas-Based Economy The Challenges Facing India on its Road to a Gas-Based Economy 1 About KAPSARC The King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC) is a non-profit global institution dedicated to independent research into energy economics, policy, technology and the environment across all types of energy. KAPSARC’s mandate is to advance the understanding of energy challenges and opportunities facing the world today and tomorrow, through unbiased, independent, and high-caliber research for the benefit of society. KAPSARC is located in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Legal Notice © Copyright 2018 King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC). No portion of this document may be reproduced or utilized without the proper attribution to KAPSARC. The Challenges Facing India on its Road to a Gas-Based Economy 2 Key Points ndian policymakers have stressed the role and relevance of natural gas in India’s overall energy mix in the 21st century but expectations of its share have been scaled back. For example, the Hydrocarbon Vision 2025, released in 1999, projected the share of gas would reach 20 percent of the primary energy Imix by 2025, while India’s current vision puts this target at 15 percent by 2030. Now, however, India’s climate change pledge at the United Nations Conference of Parties 21 (COP21) is set to reverse this with policies to promote gas in industry and transportation as well as its complementary role in achieving ambitious renewable energy targets in the long term. -

Fuel Management of Coal Based Power Stations of NTPC Limited

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Fuel Management of Coal Based Power Stations of NTPC Limited Union Government (Commercial) Ministry of Power Report No. 35 of 2016 (Performance Audit) Table of Contents Chapter Description Page No. Preface i Executive Summary iii 1 Introduction 1 2 Audit Framework 5 3 Procurement of Domestic Coal 7 4 Import of Coal 19 5 Assessment of Quality and Quantity of Coal 25 6 Coal Supply Management 35 7 Consumption of Coal by Power Stations 41 8 Conclusion and Recommendations 45 Annexures 49 List of Abbreviations 57 Glossary of Technical Terms 59 Preface The Performance Audit Report has been prepared under the provisions of Section 19-A of the Comptroller and Auditor General’s (Duties, Powers and Conditions of Service) Act, 1971, as amended in 1984. The audit has been carried out in line with the Regulations on Audit and Accounts, 2007 and Performance Audit Guidelines, 2014 of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India. Coal cost constitutes 60 to 70 percent of the total generation tariff of coal based power stations and has significant impact on cost of supply of power to consumers. Keeping this in view, a performance audit of fuel management in coal based power stations of NTPC Limited was taken up. The performance audit covers fuel management of 13 out of 26 coal based power stations of NTPC Limited and its Joint Ventures during the period from April 2010 to March 2016. Audit wishes to acknowledge the co-operation received from NTPC Limited and Ministry of Power, Government of India at each stage of the audit process. -

FAU 2021.Cdr

Two Day International Residential Conference 9-10 April 2021 at Country Inn & Suites, Goa 10th EDITION Supported By Organised By U T I L I S A T I O N Ministry of Coal Ministry of Steel CONFERENCE Ministry of Power Ministry of Road Transport & Highways Ministry of Science & Technology AWARDS Ministry of Environment & Forest Ministry of Urban Development BOX CRICKET 2 Day Residential Conference Holiday Destination Fly Ash Utilisation Awards Live Entertainment International B2C EXPO Cooking Class for Spouse Box Cricket Tournament Accompany With Spouse Cocktail Dinner Covid-19 Precautions in Place TITLE sponsor PRINCIPAL sponsor SUPPORTING sponsor ASSOCIATE sponsors HTTPS://MISSIONENERGY.ORG/FLYASH2021/ [email protected] +91 98560 98360 Two Day International Residential Conference 10th 9-10 April 2021 at Country Inn & Suites, Goa EDITION U T I L I S A T I O N CONFERENCE AWARDS BOX CRICKET A BRIEF Tackling climate change is impossible without reducing our dependence on fossil fuels, especially coal. The problem is, coal is cheap and developing economies like India prefer low-cost fuel sources. Coal-fired plants generate 70% of India’s electricity. This, combined with the growth of coal - consuming industrial sectors like steel, is why the solid fuel source will continue to be integral to India’s economy in the next couple of decades. This is despite the government’s ambitious plans to increase generation of renewable energy. India is world’s second largest producer of coal; producing a tenth of the world’s coal and also being the second largest coal importer in the world. The Indian government has been pushing for a target of 660 Million Tonne of coal production annually by end of FY 2021, most of which will be used in the power sector. -

India's Vision to a Gas-Based Economy

CEDIGAZ Insights n° 24 October 2017 India’s vision to a gas-based economy Drivers and Challenges Sylvie Cornot-Gandolphe CEDIGAZ LNG SERVICE A COMPLETE DATA SERVICE FOR THE LNG ANALYST The LNG Service provides the LNG analyst with all the data needed to follow the developments of the fast moving LNG market. The LNG Service includes comprehensive, quarterly updated, worldwide databases on liquefaction projects, regasification projects, long-term gas supply contracts and LNG trade between countries, as well as monthly bulletins on traded volumes and prices. The company reports allow for an easy assessment and benchmarking of the main players in the market and the CEDIGAZ LNG Outlook provides CEDIGAZ’s views on medium and long-term LNG market perspectives. FEATURES DATABASES Liquefaction plants: More than 150 existing and planned liquefaction facilities. Quarterly update. Regasification terminals: More than 200 existing or planned regasification terminals in the world. Quarterly update. Long-term Supply contracts: Over 200 sales/tolling contracts currently in force plus contracts with projects under development. Quarterly update. LNG trade: Annual LNG flows between exporting and importing countries since 1970. LNG MONTHLY BULLETIN M onthly LNG import volumes and prices* by country of origin. *when available CEDIGAZ LNG OUTLOOK CEDIGAZ’s medium and long-term perspectives on LNG supply and demand. COMPANY REPORTS A summary of the information of the LNG databases by company. DOWNLOAD SAMPLES: http://www.cedigaz.org/products/LNG%20Service/cedigaz-lng-service.aspx PRICE 2018 CEDIGAZ Full & Corporate Members € 3 705 CEDIGAZ Associate & Corresponding Members € 5 410 Non members € 9 270 CONTACT US Contact: [email protected] CEDIGAZ +33 1 47 52 67 20 1 et 4 Avenue de Bois-Préau Website: www.cedigaz.org 92852 Rueil Malmaison - France October 2017 India’s vision to a gas-based economy. -

PPAC Cover Nov 2020 Final

Preface The Oil and Gas sector in the country is constantly evolving with a great thrust towards alternate fuels by way of policy intervention, technology and innovation to create a sustainable energy which is accessible to all. The dominance of India in the world energy landscape is apparent with being the third largest energy consumer in the world and having recorded a CAGR of 4.7% in energy consumption for last decade as compared to 1.9% of the world. With a vibrant population of 1.4 billion which is equivalent to 17.7% of world population and the third largest economy (PPP) in the world, India is and will be a key player in the world energy markets. Around 36% of India’s energy need is met by the Oil & Gas sector as of 2019. Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell (PPAC), is an attached office of the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (MOP&NG), Government of India and undertakes analysis of trends of consumption, pricing, subsidy and new developments in domestic Oil and Gas energy sector. It is a nodal hub for data in the on the Oil & Gas sector and publishes the aggregated data on an industry basis on its website www.ppac.gov.in. The data is obtained from the Public Sector companies, Government agencies as well as the Private companies. Oil & Gas statistics is a crucial input for many stakeholders that include the Government, academia, industry and research agencies. Consistent and accurate data enable both decision making and policy making. Publication entitled ‘Ready Reckoner’ is brought out twice a year and endeavour is made to deliver accurate and timely information to all stakeholders. -

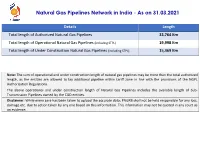

Natural Gas Pipelines Network in India - As on 31.03.2021

Natural Gas Pipelines Network in India - As on 31.03.2021 Details Length Total length of Authorized Natural Gas Pipelines 33,764 Km Total length of Operational Natural Gas Pipelines (including STPL) 19,998 Km Total length of Under Construction Natural Gas Pipelines (including STPL) 15,369 Km Note: The sum of operational and under construction length of natural gas pipelines may be more than the total authorized length, as the entities are allowed to lay additional pipeline within tariff zone in line with the provisions of the NGPL Authorization Regulations. The above operational and under construction length of Natural Gas Pipelines includes the available length of Sub- Transmission Pipelines owned by the CGD entities. Disclaimer: While every care has been taken to upload the accurate data; PNGRB shall not be held responsible for any loss, damage etc. due to action taken by any one based on this information. This information may not be quoted in any court as an evidence. List of Abbreviations AGCL Assam Gas Company Limited HEPL H-Energy Private Limited NGPL Naveriya Gas Private Limited AGPKLPL AGP Karaikal LNG Private Limited HNGPL Haridwar Natural Gas Private Limited ONGC Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited APCPL Astha Power Corporation Private HPGGG High Pressure Gujarat Gas Grid OPaL ONGC Petro addition Limited Limited APGDC Andhra Pradesh Gas Distribution HPOIL HPOIL Gas Private Limited PIL Pipelines Infrastructure Limited Corporation Limited BGL Bhagyanagar Gas Limited HPPL Hooghly Pipelines Private Limited RCIPL Recasil Ceramics Industries Private Limited BGRL Bharat Gas Resources Limited HVJ Integrated Hazira-Vijaipur-Jagdishpur RGPL Reliance Gas Pipelines Limited NGPL CGSML Charotar Gas Sahakari Mandali IGGL Indradhanush Gas Grid Limited SCPL Silica Ceramica Private Limited Limited CUGL Central UP Gas Limited IGL Indraprastha Gas Limited SEIL Steel Exchange India Limited DFPCL Deepak Fertilizer and Petrochemical IMC IMC Limited SnGL Sanwariya Gas Limited Corporation Ltd. -

Global Coal Risk Assessment: Data Analysis and Market Research

Working Paper GLOBAL COAL RISK ASSESSMENT: Data ANALYSIS AND MARKET RESEARCH AILUN YANG AND YIYUN CUI KEY FINDINGS CONTENTS 1. According to IEA estimates, global coal consumption Introduction ..................................................................2 reached 7,238 million tonnes in 2010. China account- ed for 46 percent of consumption, followed by the Part I: Proposed Coal-Fired Plants ..................................2 United States (13 percent), and India (9 percent). Part II: Existing Coal-Fired Plants ..................................10 Part III: Global Coal Trade .............................................12 2. According to WRI’s estimates, 1,199 new coal-fired Part IV: Coal Finance ...................................................18 plants, with a total installed capacity of 1,401,278 megawatts (MW), are being proposed globally. These Part V: Data Gap .........................................................22 projects are spread across 59 countries. China and Appendix – Complete List of India together account for 76 percent of the proposed Proposed New Coal-Fired Plants ..............................26 new coal power capacities. 3. New coal-fired plants have been proposed in 10 de- veloping countries: Cambodia, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Laos, Morocco, Namibia, Oman, Senegal, Sri Lanka, and Uzbekistan. Currently, there is limited Disclaimer: Working Papers contain preliminary or no capacity for domestic coal production in any of research, analysis, findings, and recommendations. They these countries. are circulated to stimulate timely discussion and critical feedback and to influence ongoing debate on emerging 4. Our analysis found that 483 power companies have issues. Most working papers are eventually published in proposed new coal-fired plants. With 66 proposed another form and their content may be revised. projects, Huaneng (Chinese) has proposed the most, followed by Guodian (Chinese), and NTPC (Indian).