EPHEMERAL GAMES Is It Barbaric to Design Videogames a Er Auschwitz? Gonzalo Frasca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian Cinema As Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr

ENGL 2090: Italian Cinema as Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr. Lisa Verner [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course surveys Italian cinema during the postwar period, charting the rise and fall of neorealism after the fall of Mussolini. Neorealism was a response to an existential crisis after World War II, and neorealist films featured stories of the lower classes, the poor, and the oppressed and their material and ethical struggles. After the fall of Mussolini’s state sponsored film industry, filmmakers filled the cinematic void with depictions of real life and questions about Italian morality, both during and after the war. This class will chart the rise of neorealism and its later decline, to be replaced by films concerned with individual, as opposed to national or class-based, struggles. We will consider the films in their historical contexts as literary art forms. REQUIRED TEXTS: Rome, Open City, director Roberto Rossellini (1945) La Dolce Vita, director Federico Fellini (1960) Cinema Paradiso, director Giuseppe Tornatore (1988) Life is Beautiful, director Roberto Benigni (1997) Various articles for which the instructor will supply either a link or a copy in an email attachment LEARNING OUTCOMES: At the completion of this course, students will be able to 1-understand the relationship between Italian post-war cultural developments and the evolution of cinema during the latter part of the 20th century; 2-analyze film as a form of literary expression; 3-compose critical and analytical papers that explore film as a literary, artistic, social and historical construct. GRADES: This course will require weekly short papers (3-4 pages, double spaced, 12- point font); each @ 20% of final grade) and a final exam (20% of final grade). -

Ephemeral Games: Is It Barbaric to Design Videogames After Auschwitz?

Ephemeral games: Is it barbaric to design videogames after Auschwitz? © 2000 Gonzalo Frasca ([email protected]) Reproduction forbidden without written authorization from the autor. Originally published in the Cybertext Yearbook 2000. According to Robert Coover, if you are looking for "serious" hypertext you should visit Eastgate.com. While, of course, "seriousness" is hard to define, we can at least imagine what we are not going to find in these texts. We are not probably going to find princesses in distress, trolls and space ships with big laser guns. So, where should we go if we are looking for "serious" computer games? As far as we know, nowhere. The reason is simple: there is an absolute lack of "seriousness" in the computer game industry. Currently, videogames are closer to Tolkien than to Chekhov; they show more influence from George Lucas rather than from François Truffaut. The reasons are probably mainly economical. The industry targets male teenagers and children and everybody else either adapts to that content or looks for another form of entertainment. However, we do not believe that the current lack of mature, intellectual content is just due to marketing reasons. As we are going to explore in this paper, current computer game design conventions have structural characteristics that prevent them to deal with "serious" content. We will also suggest different strategies for future designers in order to overcome some of these problematic issues. For the sake of our exposition, we will use the Holocaust as an example of "serious" topic, because it is usually treated with a mature approach, even if crafting a comedy, as Roberto Benigni recently did in his film "Life is Beautiful". -

Course Outline 3/23/2018 1

5055 Santa Teresa Blvd Gilroy, CA 95023 Course Outline COURSE: HUM 6 DIVISION: 10 ALSO LISTED AS: TERM EFFECTIVE: Fall 2018 CURRICULUM APPROVAL DATE: 03/12/2018 SHORT TITLE: CONTEMPORARY WORLD CINEMA LONG TITLE: Contemporary World Cinema Units Number of Weeks Contact Hours/Week Total Contact Hours 3 18 Lecture: 3 Lecture: 54 Lab: 0 Lab: 0 Other: 0 Other: 0 Total: 3 Total: 54 COURSE DESCRIPTION: This class introduces contemporary foreign cinema and includes the examination of genres, themes, and styles. Emphasis is placed on cultural, economic, and political influences as artistically determining factors. Film and cultural theories such as national cinemas, colonialism, and orientalism will be introduced. The class will survey the significant developments in narrative film outside Hollywood. Differing international contexts, theoretical movements, technological innovations, and major directors are studied. The class offers a global, historical overview of narrative content and structure, production techniques, audience, and distribution. Students screen a variety of rare and popular films, focusing on the artistic, historical, social, and cultural contexts of film production. Students develop critical thinking skills and address issues of popular culture, including race, class gender, and equity. PREREQUISITES: COREQUISITES: CREDIT STATUS: D - Credit - Degree Applicable GRADING MODES L - Standard Letter Grade REPEATABILITY: N - Course may not be repeated SCHEDULE TYPES: 02 - Lecture and/or discussion STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Demonstrate the recognition and use of the basic technical and critical vocabulary of motion pictures. 3/23/2018 1 Measure of assessment: Written paper, written exams. Year assessed, or planned year of assessment: 2013 2. Identify the major theories of film interpretation. -

Copyright by Jodi Heather Egerton 2006

Copyright by Jodi Heather Egerton 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Jodi Heather Egerton Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “Kush mir in tokhes!”: Humor and Hollywood in Holocaust Films of the 1990s Committee: _________________________ Mia Carter, Co-Supervisor _________________________ Ann Cvetkovich, Co-Supervisor _________________________ Pascale Bos _________________________ John Ruszkiewicz _________________________ Phillip Barrish “Kush mir in tokhes!”: Humor and Hollywood in Holocaust Films of the 1990s by Jodi Heather Egerton, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2006 Dedication For Grandma Gertie and Grandma Gert, for filling me with our stories. For Owen, my beloved storyteller. For Arden, the next storyteller. Acknowledgements Thank you to Ann Cvetkovich and Mia Carter, for your unending support and insight, to Sabrina Barton and Phil Barrish, for guiding me especially in the early stages of the project, to Pascale Bos, for the scoop, and to John Ruszkiewicz, for helping me to discover who I am as a teacher and a scholar. Thank you to my early academic mentors, Abbe Blum, Nat Anderson, Alan Kuharski and Tom Blackburn, and my early academic colleagues Rachel Henighan, Megin Charner, and Liza Ewen, my Swarthmore community who continue to inspire me. Thank you to Joyce Montalbano, my second and fifth grade teacher, who honored the spark she saw in me and showed me the excitement of an intellectual challenge. Thank you to Eliana Schonberg and Ashley Shannon, because I can’t imagine any of this without you. -

92ND ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS® SIDEBARS (Revised)

92ND ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS® SIDEBARS (revised) A record 64 women were nominated, one third of this year’s nominees. Emma Tillinger Koskoff (Joker, The Irishman) and David Heyman (Marriage Story, Once upon a Time...in Hollywood) are the sixth and seventh producers to have two films nominated for Best Picture in the same year (since 1951 when individual producers first became eligible as nominees in the category). Previous producers were Francis Ford Coppola and Fred Roos (1974), Scott Rudin (2010), Megan Ellison (2013), and Steve Golin (2015). The Best Picture category expanded from five to up to ten films with the 2009 Awards year. Parasite is the eleventh non-English language film nominated for Best Picture and the sixth to be nominated for both International Feature Film (formerly Foreign Language Film) and Best Picture in the same year. Each of the previous five (Z, 1969; Life Is Beautiful, 1998; Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, 2000; Amour, 2012; Roma, 2018) won for Foreign Language Film but not Best Picture. In April 2019, the Academy’s Board of Governors voted to rename the Foreign Language Film category to International Feature Film. With his ninth Directing nomination, Martin Scorsese is the most-nominated living director. Only William Wyler has more nominations in the category, with a total of 12. In the acting categories, five individuals are first-time nominees (Antonio Banderas, Cynthia Erivo, Scarlett Johansson, Florence Pugh, Jonathan Pryce). Eight of the nominees are previous acting winners (Kathy Bates, Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hanks, Anthony Hopkins, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci, Charlize Theron, Renée Zellweger). Adam Driver is the only nominee who was also nominated for acting last year. -

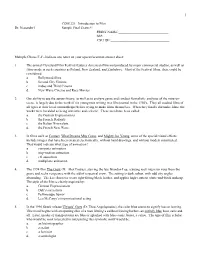

COM 221: Introduction to Film Dr. Neuendorf Sample Final Exam #1 PRINT NAME: SS

1 COM 221: Introduction to Film Dr. Neuendorf Sample Final Exam #1 PRINT NAME:_____________________________ SS#:______________________________________ CSU ID#:__________________________________ Multiple Choice/T-F--Indicate one letter on your opscan/scantron answer sheet: 1. The annual Cleveland Film Festival features American films not produced by major commercial studios, as well as films made in such countries as Poland, New Zealand, and Zimbabwe. Most of the Festival films, then, could be considered: a. Bollywood films b. Second City Cinema c. indies and Third Cinema d. New Wave Cinema and Race Movies 2. Our ability to use the auteur theory, as well as to analyze genre and conduct formalistic analyses of the mise-en- scene, is largely due to the work of six young men writing in a film journal in the 1950's. They all studied films of all types at their local cinematheque before trying to make films themselves. When they finally did make films, the works were heralded as being inventive and eclectic. These men have been called: a. the German Expressionists b. the French Dadaists c. the Italian Neorealists d. the French New Wave 3. In films such as Contact, What Dreams May Come, and Mighty Joe Young, some of the special visual effects include images that have been created electronically, without hand drawings, and without models constructed. That would indicate what type of animation? a. computer animation b. stop-motion animation c. cel animation d. multiplane animation 4. The 1994 film The Crow (D: Alex Proyas), starring the late Brandon Lee, a young rock musician rises from the grave and seeks vengeance with the aid of a spectral crow. -

Italian Films (Updated April 2011)

Language Laboratory Film Collection Wagner College: Campus Hall 202 Italian Films (updated April 2011): Agata and the Storm/ Agata e la tempesta (2004) Silvio Soldini. Italy The pleasant life of middle-aged Agata (Licia Maglietta) -- owner of the most popular bookstore in town -- is turned topsy-turvy when she begins an uncertain affair with a man 13 years her junior (Claudio Santamaria). Meanwhile, life is equally turbulent for her brother, Gustavo (Emilio Solfrizzi), who discovers he was adopted and sets off to find his biological brother (Giuseppe Battiston) -- a married traveling salesman with a roving eye. Bicycle Thieves/ Ladri di biciclette (1948) Vittorio De Sica. Italy Widely considered a landmark Italian film, Vittorio De Sica's tale of a man who relies on his bicycle to do his job during Rome's post-World War II depression earned a special Oscar for its devastating power. The same day Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) gets his vehicle back from the pawnshop, someone steals it, prompting him to search the city in vain with his young son, Bruno (Enzo Staiola). Increasingly, he confronts a looming desperation. Big Deal on Madonna Street/ I soliti ignoti (1958) Mario Monicelli. Italy Director Mario Monicelli delivers this deft satire of the classic caper film Rififi, introducing a bungling group of amateurs -- including an ex-jockey (Carlo Pisacane), a former boxer (Vittorio Gassman) and an out-of-work photographer (Marcello Mastroianni). The crew plans a seemingly simple heist with a retired burglar (Totó), who serves as a consultant. But this Italian job is doomed from the start. Blow up (1966) Michelangelo Antonioni. -

BFI Film Quiz – August 2015

BFI Film Quiz – August 2015 General Knowledge 1 The biographical drama Straight Outta Compton, released this Friday, is an account of the rise and fall of which Los Angeles hip hop act? 2 Only two films have ever won both the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and the Academy Award for Best Picture. Name them. 3 Which director links the films Terms of Endearment, Broadcast News & As Good as it Gets, as well as TV show The Simpsons? 4 Which Woody Allen film won the 1978 BAFTA Award for Best Film, beating fellow nominees Rocky, Net- work and A Bridge Too Far? 5 The legendary Robert Altman was awarded a BFI Fellowship in 1991; but which British director of films including Reach for the Sky, Educating Rita and The Spy Who Loved Me was also honoured that year? Italian Film 1 Name the Italian director of films including 1948’s The Bicycle Thieves and 1961’s Two Women. 2 Anna Magnani became the first Italian woman to win the Best Actress Academy Award for her perfor- mance as Serafina in which 1955 Tennessee Williams adaptation? 3 Name the genre of Italian horror, popular during the 1960s and ‘70s, which includes films such as Suspiria, Black Sunday and Castle of Blood. 4 Name Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1961 debut feature film, which was based on his previous work as a novelist. 5 Who directed and starred in the 1997 Italian film Life is Beautiful, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, amongst other honours. -

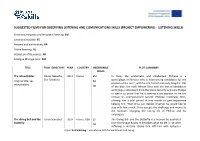

Project Empowering - Listening Skills)

SUGGESTED FILMS FOR OBSERVING LISTENING AND COMUNICATIONS SKILLS (PROJECT EMPOWERING - LISTENING SKILLS) Emotions, empathy and empathic listening: EM Emotional stability: ES Respect and authenticity: RA Active listening: AL Activation of Resources: AR Dialogue Management: DM TITLE FILM DIRECTOR YEAR COUNTRY OBSERVABLE PLOT SUMMARY SKILLS The Intouchables Olivier Nakache, 2011 France EM In Paris, the aristocratic and intellectual Philippe is a Original title: Les Éric Toledano RA quadriplegic millionaire who is interviewing candidates for the intouchables position of his carer, with his red-haired secretary Magalie. Out AR of the blue, the rude African Driss cuts the line of candidates and brings a document from the Social Security and asks Phillipe to sign it to prove that he is seeking a job position so he can receive his unemployment benefit. Philippe challenges Driss, offering him a trial period of one month to gain experience helping him. Then Driss can decide whether he would like to stay with him or not. Driss accepts the challenge and moves to the mansion, changing the boring life of Phillipe and his employees. The diving bell and the Julian Schnabel 2007 France, USA ES The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is a memoir by journalist butterfly AR Jean-Dominique Bauby. It describes what his life is like after suffering a massive stroke that left him with locked-in Project EmPoWEring - Educational Path for Emotional Well-being Original title: Le DM syndrome. It also details what his life was like before the scaphandre et le stroke. papillon On December 8, 1995, Bauby, the editor-in-chief of French Elle magazine, suffered a stroke and lapsed into a coma. -

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY , Florence Italy Fall 2010 Syllabus for History of Italian Cinema

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY , Florence Italy Fall 2010 Syllabus for History of Italian Cinema Class Meetings: Wednesdays 4:30-7:15 pm Screenings: Film Screenings: Monday or Tuesday 6:00-8:00 pm Professor: Tina Fallani Benaim [email protected] Office Hours: after class or by appointment Required Reading: Peter Bondanella: Italian Cinema (Continuum Third Edition 2003) Millicent Marcus: In the Light of Neorealism (Princeton university Press 1986) Chapters 1,2,6, included in the Course Reader Packet of Articles and Reviews in the Course Reader (see weekly calendar) that includes Essays by: Bazin, Burke, Chatman, Michaiczyck Assignments: Attendance to lectures and screenings One midterm paper and a final test (essay questions) covering the entire program Oral presentations Grading System: Participation 20% Oral Presentations 20% Mid-term exam 25% Final Exam 35% Course description The course introduces the student to the world of Italian Cinema. In the first part the class will be analysing Neorealism , a cinematic phenomenon that deeply influenced the ideological and aesthetic rules of film art. In the second part we will concentrate on the films that mark the decline of Neorealism and the talent of "new" auteurs such as Fellini and Antonioni . The last part of the course will be devoted to the cinema from 1970's to the present in order to pay attention to the latest developments of the Italian industry. The course is a general 1 1 analysis of post-war cinema and a parallel social history of this period using films as "decoded historical evidence". Together with masterpieces such as "Open City" and "The Bicycle Thief" the screenings will include films of the Italian directors of the "cinema d'autore" such as "The Conformist", "Life is Beautiful" and the 2004 candidate for the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, “I am not scared”. -

LS 180.01: Introduction to Film

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Fall 9-1-2000 LS 180.01: Introduction to Film Lynn Purl University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Purl, Lynn, "LS 180.01: Introduction to Film" (2000). Syllabi. 5178. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/5178 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Autumn 2000 Lynn Purl Liberal Studies 180 [email protected] Intro to Film Office: LA 155 M 1:10-4:00, UC Theatre 243 -5314 W 1:10-3:00, GBB L09 Home: 721-0517 Mailbox: Liberal Studies office, LA 101 Office hours: W 12:00-1:00,Th 2:00-3:30, and by appointment Course description:This course will serve as an introduction to basic concepts of film and film theory. The goal is to encourage you to become more sophisticated viewers and consumers of movies, with an ability to view films as art, as marketplace commodities, as technology, as historical documents, and as cultural and ideological forces. I also hope you will increase your ability to organize and articulate your insights, both in class discussions and in writing. Required text:Understanding Movies, eighth edition, by Louis Giannetti Course requirements:Quizzes, final, term paper, and discussion paragraphs, as well as regular attendance and participation. -

Following Is a Listing of Public Relations Firms Who Have Represented Films at Previous Sundance Film Festivals

Following is a listing of public relations firms who have represented films at previous Sundance Film Festivals. This is just a sample of the firms that can help promote your film and is a good guide to start your search for representation. 11th Street Lot 11th Street Lot Marketing & PR offers strategic marketing and publicity services to independent films at every stage of release, from festival premiere to digital distribution, including traditional publicity (film reviews, regional and trade coverage, interviews and features); digital marketing (social media, email marketing, etc); and creative, custom audience-building initiatives. Contact: Lisa Trifone P: 646.926-4012 E: [email protected] www.11thstreetlot.com 42West 42West is a US entertainment public relations and consulting firm. A full service bi-coastal agency, 42West handles film release campaigns, awards campaigns, online marketing and publicity, strategic communications, personal publicity, and integrated promotions and marketing. With a presence at Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Tribeca, SXSW, New York and Los Angeles film festivals, 42West plays a key role in supporting the sales of acquisition titles as well as launching a film through a festival publicity campaign. Past Sundance Films the company has represented include Joanna Hogg’s THE SOUVENIR (winner of World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic), Lee Cronin’s THE HOLE IN THE GROUND, Paul Dano’s WILDLIFE, Sara Colangelo’s THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER (winner of Director in U.S. competition), Maggie Bett’s NOVITIATE