(2020) History and Archaeology of the St Wulstan's Hospital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Worcester Great Mal Vern 24Pp DL TT Booklet REV4 Layout 1 27/04/2010 12:28 Page 2

24pp DL TT Booklet REV4_Layout 1 27/04/2010 12:28 Page 1 Red line 44 44A 45 Your local bus guide to services in Worcester Great Mal vern 24pp DL TT Booklet REV4_Layout 1 27/04/2010 12:28 Page 2 Welcome to th Welcome to your new information guide for bus services between Worcester and Great Malvern also serving Ledbury 44/44A/44B & 45. For connecting bus services, serving other parts of the Malvern Hills please see pages 25-27. These services provide a circular route around Malvern giving direct links to Great Malvern, Malvern Retail Park, Worcester City Centre & Worcestershire Royal Hospital. Also included is service 44B which runs to Ledbury via Malvern Hills & British Camp on Sundays & Bank Holiday Mondays during the summer. Buses run every 15 minutes throughout the main part of the day on Monday to Saturdays and every hour on Sundays. Modern, high-specification buses operate on this service making your journey enjoyable and more comfortable, a wide entrance, low floor and kneeling facility gives easy access for wheelchairs and buggies. 2 24pp DL TT Booklet REV4_Layout 1 27/04/2010 12:29 Page 3 th e Red line! Customer Feedback We welcome your feedback on all areas of service we provide to you. Your comments are important to us and help us improve the areas where you feel we are not delivering a satisfactory service. Contact our Customer Services on Monday to Thursday 0830 to 1700 0800 587 7381 Friday 0830 to 1630 Alternatively, click the 'Contact Us' section on our website, www.firstgroup.com. -

Choice Plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 3 Home HOME Choice CHOICE .ORG.UK Plus PLUS

home choice plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 3 Home HOME Choice CHOICE .ORG.UK Plus PLUS ‘Working in partnership to offer choice from a range of housing options for people in housing need’ home choice plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 4 The Home Choice Plus process The Home Choice Plus process 2 What is a ‘bid’? 8 Registering with Home Choice plus 3 How do I bid? 9 How does the banding system work? 4 How will I know if I am successful? 10 How do I find available properties? 7 Contacts 11 What is Home Choice Plus? Home Choice Plus has been designed to improve access to affordable housing. The advantage is that you only register once and the scheme allows you to view and bid on available properties for which you are eligible across all of the districts. Home Choice Plus has been developed by a number of Local Authorities and Housing Associations working in partnership. Home Choice Plus is a way of allocating housing and advertising other housing options across the participating Local Authority areas. (Home Choice Plus will also be used for advertising other housing options such as private rents and intermediate rents). This booklet explains how to look for housing across all of the Districts involved in this scheme. Please see website for further information. Who is eligible to join the Home Choice Plus register? • Some people travelling to the United Kingdom are not entitled to Housing Association accommodation on the basis of their immigration status. • You may be excluded if you have a history of serious rent arrears or anti social behaviour. -

Malvern Hills Joint Advisory Committee

AGENDA ITEM 8 MALVERN HILLS AONB JOINT ADVISORY COMMITTEE 23 APRIL 2021 INFORMATION ITEMS Management Plan ref. Project (abridged) LP3 Promote positive Land management advice change to landowners, The Unit commissioned call-off advice from a land managers, developers management advisor towards the end of 2019/20 and again etc. in 2020/21. This has helped us to step-up our conservation advisory work with owners and farmers with 6 advisory visits taking place in 2020/21. 2 owners also benefitted from meadow restoration plans produced by the Herefordshire Meadows Group. 1 owner received support with preparing and submitting a Woodland Management Plan. BP2 Conserve, enhance Biodiversity grants and expand key 8 biodiversity grants were provided to support work as habitats and diverse as orchard creation at Barton Court, planting a new populations of key woodland in Malvern Wells, hedge laying in Suckley and species in line with fencing a ‘wet’ field in Colwall. local biodiversity priorities The volunteers of Colwall Orchard Group received a grant to restore traditional orchards in the parish, and so planted 73 trees in 10 orchards. BP4 Improve Nature Recovery Planning knowledge and The data assessment and mapping phase of a Nature understanding of the Recovery Plan is almost complete. Baseline and opportunity AONB’s biodiversity maps have been created for ecological opportunities and for a range of Ecosystem Services in the area. We have attempted to integrate landscape and the historic environment into this work too. Partners from a number of bodies have made a contribution to this work. FP6 – Encourage the Countryside Stewardship Facilitation Fund take-up of options and An event on shooting and conservation in woodlands was management practices held on-line in December 2020. -

Lime Kilns in Worcestershire

Lime Kilns in Worcestershire Nils Wilkes Acknowledgements I first began this project in September 2012 having noticed a number of limekilns annotated on the Ordnance Survey County Series First Edition maps whilst carrying out another project for the Historic Environment Record department (HER). That there had been limekilns right across Worcestershire was not something I was aware of, particularly as the county is not regarded to be a limestone region. When I came to look for books or documents relating specifically to limeburning in Worcestershire, there were none, and this intrigued me. So, in short, this document is the result of my endeavours to gather together both documentary and physical evidence of a long forgotten industry in Worcestershire. In the course of this research I have received the help of many kind people. Firstly I wish to thank staff at the Historic Environmental Record department of the Archive and Archaeological Service for their patience and assistance in helping me develop the Limekiln Database, in particular Emma Hancox, Maggi Noke and Olly Russell. I am extremely grateful to Francesca Llewellyn for her information on Stourport and Astley; Simon Wilkinson for notes on Upton-upon-Severn; Gordon Sawyer for his enthusiasm in locating sites in Strensham; David Viner (Canal and Rivers Trust) in accessing records at Ellesmere Port; Bill Lambert (Worcester and Birmingham Canal Trust) for involving me with the Tardebigge Limekilns Project; Pat Hughes for her knowledge of the lime trade in Worcester and Valerie Goodbury -

Malvern Hills Site Assessments August 2019 LC-503 Appendix B MH Sites 1 310519CW.Docx Appendix B: Malvern Hills Site Assessments

SA of the SWDPR: Malvern Hills Site Assessments August 2019 LC-503_Appendix_B_MH_Sites_1_310519CW.docx Appendix B: Malvern Hills Site Assessments © Lepus Consulting for Malvern Hills District Council Bi SA of the SWDPR: Malvern Hills Site Assessments August 2019 LC-503_Appendix_B_MH_Sites_1_310519CW.docx Appendix B Contents B.1 Abberley ..................................................................................................................................... B1 B.2 Astley Cross ............................................................................................................................. B8 B.3 Bayton ...................................................................................................................................... B15 B.4 Bransford ............................................................................................................................... B22 B.5 Broadwas ............................................................................................................................... B29 B.6 Callow End ............................................................................................................................ B36 B.7 Clifton upon Teme ............................................................................................................. B43 B.8 Great Witley ........................................................................................................................... B51 B.9 Hallow ..................................................................................................................................... -

Old Hills Malvern Headlines

Old Hills Malvern Headlines th 25 October 2020 Keeping you in touch with your churches across Powick, Callow End, Guarlford and Madresfield with Newland SERVICES FOR THE COMING PERIOD Sunday Evening Worship Sunday Gathered Worship 25th October th 25 October 5.30pm – Contemplative Evening Prayer 9.30am Living Communion at Callow End 1st November 11.00am Guarlford and Madresfield with 5.30pm- All Souls Open Memorial Service Newland Annual Meeting and Service of On Zoom Video Conferencing Thanksgiving at Madresfield Please contact us for access codes st 1 November All Saints Day Thursday Night Prayers th th 10.30am Zoom Service 29 October and 5 November 8.30pm On Zoom Video Conferencing Remembrance Sunday – 8th November Please contact us for access codes 9. 30am Wreath Laying at the war memorial and 2 minutes silence at Guarlford 10.45am Church Service for Remembrance Sunday (Rev Canon Claire Griffiths) at Madresfield 10.50am The Powick Parish Royal British Legion Remembrance at Callow End War Memorial In all situations where gatherings occur around or in the vicinity of war memorials, remember the Rule of Six and Social Distancing provisions. You are strongly urged to Remember this year in your own way, in your own home with a poppy A set of weekly intercessions for personal use is available each week on the website. Rev Gary is on holiday during half term VICAR’S BLOG! week (w/c 26th October), hopefully away but that depends on the virus! It is with sadness that I write to let you know that our He will leave the parishes Parishes' patron, Lady Morrison, passed away after a in the capable hands of the churchwardens.... -

Worcestershire Malvern

44 •' Malvern Worcestershire I --------------------------------------------~----------------------------- "Eastwick", Graham rd Evans J & Son, Newtown SMITH J H, purveyor of meat, K.notsford Lodge, Abbey rd Ford R, Cowleigh road, North West Malvern ~on t r o se Boarding H o u se, Malvern Spencer C, Court rd Graham rd J AMES WILLIAM, builder & Sutton E, Wells td, Malvern Wells Scarhorough House, 'North Mal- contractor, plumber, painter & THE COLWALL CAS R v-ern-IM,m Bake•., prtoprietress decorator, The Wyche, Upper MEAT SUPPLY C0.1 Col- Sutherland Boarding Houser Colwall. Tel. No. 47 Colwall wall. Fresh supply daily .Abbey rd Layton M & Son, 3 Park Oottruge, WALKER W R, family butcher Vaughan's Lodge Malvern Wells. Court rd Malvern Wells. Families waited Lewis A G, West. Malvern upon daily for <nders. Estab- McCANN T W, builder, con- Jjshed 1835. Tel. 10 COlwall traclor and undertaker, etc., Whittle R, Lower Newtown 13 OOXSELLERS. Worcester rd, \Malvern Link. Whittle T, Upper Wyche Tel. No. 271 Baylis S & F Belle Vue Terrace Porter W, Wells rd JONES C ' second-hand book- Prioo W T, West Malvern seller, Library, Cheap Music & Wilesmith M, builder, Malvern 'fypewriting Offices, 6 Colonn- Link CAB & CAR PROPRIETORS. ade WILLIAMS F, builder, carpen- Thompson J, Church st ter, joiner and undertaker, etc. Allsep F J, Gra.ham Livery Barnards Green rd &tables, Gmham rd Bannister H, W .oodbine Co.bba,ge, BOOT AND SHOE • West Malvern MAKERS. Go bey W, The Mews, Worcester BUILDERS' MERCHANTS. rd, Malvern Link BADHAM G T, boot and shoe Griffiths J B, Church st maker, Chester House, Col wall. -

Old Hills Malvern Headlines

Old Hills Malvern Headlines th 11 October 2020 Keeping you in touch with your churches across Powick, Callow End, Guarlford and Madresfield with Newland SERVICES FOR THE COMING PERIOD Sunday Evening Worship Sunday Gathered Worship 11th October th 11 October 5.30pm – Contemplative Evening Prayer – Kindness 9.30am BCP Holy Communion at Callow End 18th October 11.00am BCP Holy Communion at Madresfield 5.30pm- Contemplative Evening Prayer - Peace th 18 October On Zoom Video Conferencing 9.30am Harvest Communion at Guarlford Please contact us for access codes th (deferred from 4 October) 11.00am Powick Parish Annual Meeting and Thursday Night Prayers Service of Thanksgiving at Powick 15th and 22nd October 8.30pm On Zoom Video Conferencing A set of weekly intercessions for personal use is available each week on the website. Please contact us for access codes Annual Parochial Church Council Meetings VICAR’S BLOG! Sunday 18th October Harvest has been a very different experience for us all this Powick Parish at St Peter's Church Powick. - as year. Rather than lugging tins and packets into well part of the Sunday worship - from 11am (the decorated churches, we have used our Harvest of talents to service and meeting will finish by 12.30pm) support Tearfund and their "Rubbish Year" projects. Thank Sunday 25th October you - the total will be advised in the next Headlines. For the Guarlford, Madresfield with Newland Parish at first time in my ministry, I had to cease worship at a church St Mary’s, Madresfield – as part of the Sunday as we were infested by flies! The weather was worship - from 11am (the service and meeting howling outside at Guarlford too. -

Malvern Walking and Cycling Guide A

To Leigh To Worcester To Worcester Sinton Cricket Ground 449 Malvern Walking and Cycling Guide A D To Leigh A KINNERSLEY O R Y Sinton E ROAD FK B AL H 4 5 MALTON 0 Newland CLOSE 3 ROAD OAD STWARD Lower L R WE ITA OSP S TANHO H A B D D N E Howsell REDWING D V A A CLOSE E D FIELDFARE P US A O R O Sports O IP LE AY R T Y W E R R CLOSE N E SCE M LAN R CRE IC HA Ground Y R D A L W E MANOR EL E R T PALE CLOSE A L CRE H S TW E G E S R C W ROA SCEN A S U R HILL VIE D E B O Y W N W M To Worcester Y A I WA T AYSON W ILL T O D A H E H D D S Upper N F E W R BU O E I COOPER M N SU ME T STREET D E S Y WALK TERCU A RFI K A Howsell RO R EL U F S D I R BRACKEN WAY LD E D ROAD D IE RD E LL NF E R E OA . L D RE KFIE W 10 AN O P Dyson Perrins G LD D A AD O R D VALE ROAD L COOPER CLOSE O C of E Sports College Malvern ST. AD BRACKEN R RO Cricket R WAY BOSBURY Retail Park O ET A N TR Ground D EN E . -

JBA Consulting Report Template 2015

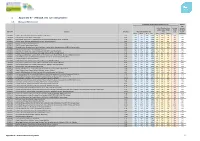

1 Appendix B – SHELAA site screening tables 1.1 Malvern Hills District Proportion of site shown to be at risk (%) Area of site Risk of flooding from Historic outside surface water (Total flood of Flood Site code Location Area (ha) Flood Zones (Total %s) %s) map Zones FZ 3b FZ 3a FZ 2 FZ 1 30yr 100yr 1,000yr (hectares) CFS0006 Land to the south of dwelling at 155 Wells road Malvern 0.21 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 6% 0% 0.21 CFS0009 Land off A4103 Leigh Sinton Leigh Sinton 8.64 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% <1% 4% 0% 8.64 CFS0011 The Arceage, View Farm, 11 Malvern Road, Powick, Worcestershire, WR22 4SF Powick 1.79 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1.79 CFS0012 Land off Upper Welland Road and Assarts Lane, Malvern Malvern 1.63 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1.63 CFS0016 Watery Lane Upper Welland Welland 0.68 0% 0% 0% 100% 4% 8% 26% 0% 0.68 CFS0017 SO8242 Hanley Castle Hanley Castle 0.95 0% 0% 0% 100% 2% 2% 13% 0% 0.95 CFS0029 Midlands Farm, (Meadow Farm Park) Hook Bank, Hanley Castle, Worcestershire, WR8 0AZ Hanley Castle 1.40 0% 0% 0% 100% 1% 2% 16% 0% 1.40 CFS0042 Hope Lane, Clifton upon Teme Clifton upon Teme 3.09 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 3.09 CFS0045 Glen Rise, 32 Hallow Lane, Lower Broadheath WR2 6QL Lower Broadheath 0.53 0% 0% 0% 100% <1% <1% 1% 0% 0.53 CFS0052 Land to the south west of Elmhurst Farm, Leigh Sinton, WR13 5EA Leigh Sinton 4.39 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 4.39 CFS0060 Land Registry. -

Worcestershire. (Kelly's

274 FAB WORCESTERSHIRE. (KELLY'S Faber Mrs. Shrawley house, Worcester Fieldwick Rev. George Thomas, Hanley Fork Alfred, 4 Elderfield villM, Coven~ road, Malvern Link Castle, Worcester try street, Kidderminster Fairley Henry, Round's green, Oldbury Finch Rev. William M.A. The Monks, Forrest Very Rev. Robert William D.D, Faram Charles, Holmden, Battenhall Chaddesley Corbett, Kidderminster The Deanery, Worcester road, Worcester Finch Michael, Camp Hillrd. Worcester ForrestE.3IBowlingGreen rd.Stourbrdg FarmerRev.W.The Crescent,Bromsgrve Finch Miss,Avondale,Bredon,Tewkesbry Forrest Saml. Hy. 4~ Church st.Oldbry Farmer F. H. Bromyard rd. Worcester Finch Mrs. Henwick road, St. John's, Forster Misses, College yard, Worcester Farmer Miss, Holy cross, Stourbridge Worcester Forsyth James, Blenhe1m lodge, Chest• Farmer Miss, Pound bank, Barnard's Finch Mrs. Inkford, Wythall, Redditch nut walk, Worcester green, Great Malvern :Finch Mrs. q Tything, Worcester Forsyth William, 6 Tything, Worcester FarmerMrs. soChester rd.Kidderminster FinchW. W. I Lansdowne cres. Worcester Forster Mrs. North Hallow, Worcester Farmer Mrs. Coney Brae, We. Malvern Fincher Mrs. r Fernleigh, Bromyard rd. Forty Miss, 2 Avenue ter. Stourbridge FarmerMrs.IField ter.Bath rd. Worcestr St. John's, Worcester Fosbroke George Haynes, Rose place, Farr Harry, I5 Richmond rd. Worcestr Findon .Alfred, z Elderfield vils. Coven- North Claines, Worcester FarrMrs.Lovela.OldSwinford,Stourbrdg try street, Kidderminster Foster Rev. Henry, jun. M.A. 5 Colleg~ Farrant Mrs. Heather bank, Welland, FindullMrs.3YewTree rd.Kidderminster grounds, Great Malvern Great Malvern FinneyMrs.Church-fields ho.Bromsgrve Foster Charles Edward, 2 Myrtle villiJS, Farrell Miss, I Battenhall place, London Finney Mrs. Raleigh villas, Finstall, Dixon's green, Dudley road, Worcester Bromsgrove Foster George, The Ha wthornes, Dixon's Farrington William Henry, r7 Rich- Finni~ Mrs. -

Recommended Local Accommodation

RECOMMENDED LOCAL ACCOMMODATION BASED IN MALVERN: The Abbey Hotel Ashbury Bed & Breakfast Morgan visitors are offered a 10% discount – quote Morgan Morgan visitors are offered a 10% discount – quote Morgan Great Malvern, Worcestershire WR14 3ET (minimum two-night stay) 1 Old Hollow, Malvern, Worcestershire WR14 4NP 01684 892332 www.sarova.com 01684 574225 www.ashburybedandbreakfast.co.uk Malvern Spa Hotel Morgan visitors are offered a 10% discount – quote Morgan10 Grovewood Road, Malvern, Worcestershire WR14 1GD 01684 898290 www.themalvernspa.com The Colwall Park Hotel Morgan visitors are offered a 10% discount – quote Morgan10 Walwyn Road, Colwall, Worcestershire WR13 6QG 01684 540000 www.colwall.co.uk Morgan Plus Six photographed at Stanbrook Abbey Hotel. The Cotford Hotel Morgan visitors are offered a 10% discount – quote Morgan BASED OUTSIDE MALVERN: 51 Graham Road, Malvern, Worcestershire WR14 2HU 01684 572427 www.cotfordhotel.co.uk Stanbrook Abbey Hotel Morgan visitors are offered a 10% discount – please enter The Cottage in The Wood Hotel PMOR17 when making a reservation. Callow End, Worcestershire. Morgan visitors are offered a 10% discount – quote Morgan 01905 409 300 [email protected] Holywell Road, Malvern, Worcestershire WR14 4LG www.handpickedhotels.co.uk/stanbrookabbey 01684 588860 www.cottageinthewood.co.uk Treherne House (Guesthouse) The Verzon House Hotel Complimentary free drink for all Morgan guests. Morgan visitors are offered a 10% discount – quote Morgan 54 Guarlford Road, Malvern, Worcestershire WR14 3QP Hereford Road, Trumpet HR8 2PZ 01684 572445 www.trehernehouse.co.uk 01531 670381 www.verzonhouse.com Air BnB Diglis House Hotel Morgan visitors are offered a 10% discount – quote Morgan Morgan visitors are offered a 10% discount – quote Morgan 207 Malvern Wells, Worcestershire Severn Street, Worcester WR1 2NF www.airbnb.co.uk/rooms/24951192 01905 353518 www.diglishousehotel.co.uk FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE VISIT OUR WEBSITE: WWW.MORGAN-MOTOR.COM/MORGAN-EXPERIENCE-CENTRE.