Community-Based Care for Older Persons Implications from China, Korea and Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Republic of Korea

The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in the Republic of Korea Samsik Lee Ae Son Om Sung Min Kim Nanum Lee Institute of Aging Society, Hanyang University Seoul, Republic of Korea The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in the Republic of Korea This report is prepared with the cooperation of HelpAge International. To cite this report: Samsik Lee, Ae Son Om, Sung Min Kim, Nanum Lee (2020), The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in in the Republic of Korea, HelpAge International and Institute of Aging Society, Hanyang University, Seoul, ISBN: 979-11-973261-0-3 Contents Chapter 1 Context 01 1. COVID -19 situation and trends 1.1. Outbreak of COVID-19 1.2. Ruling on social distancing 1.3. Three waves of COVID-19 09 2. Economic trends 2.1. Gloomy economic outlook 2.2. Uncertain labour market 2.3. Deepening income equality 13 3. Social trends 3.1. ICT-based quarantine 3.2. Electronic entry 3.3. Non-contact socialization Chapter 2 Situation of older persons Chapter 3 Responses 16 1. Health and care 47 1. Response from government 1.1. COVID-19 among older persons 1.1. Key governmental structures Higher infection rate for the young, higher death rate for the elderly 1.2. COVID-19 health and safety Critical elderly patients out of hospital Total inspections Infection routes among the elderly Cohort isolation 1.2. Healthcare system and services 1.3. Programming and services Threat to primary health system Customized care services for senior citizens Socially distanced welfare facilities for elderly people Senior Citizens' Job Project Emergency care services Online exercise 1.3. -

Resilient Seoul

SEOUL A Strategy for Urban Resilience 2019 RESILIENT 2019 RESILIENT SEOUL | A Strategy for Urban Resilience 2019 Smart Safe City for All, Seoul A Strategy for Urban Resilience 2019 3 | RESILIENT SEOUL | 1 Photo by An Yeon-soo CONTENTS 01 Introduction 04 02 Executive Summary 08 03 What is Urban Resilience? 10 04 Introducing Seoul 12 05 Seoul in Context 18 06 Seoul’s History of Disasters 20 07 Journey Towards Resilient Seoul 22 08 100RC Network 36 09 Goal 1 Governance- Resilience through Collaboration 38 A Program 1. Safety Governance Strategy Program 2. Smart Safety Net for Program 3. Climate Change Response System Urban Program 4. Proactive Management for Aging Infrastructure Resilience Program 5. Safer Neighborhoods 2019 10 Goal 2 Community- Stronger and Connected Community 66 Program 6. Connected Neighborhood for the Vulnerable Program 7. Stable and Affordable Housing for All Program 8. Childbirth and Childcare Service Program 9. Innovative Solutions in Community 11 Goal 3 Inclusive Growth- Prosperous Seoul for All 80 Program 10. Youth Welfare and Jobs Program 11. Employment Opportunities for the Elderly Program 12. Microbusiness and the Self-employed Program 13. Respect for Labor Program 14. Expansion of Social Economy 12 What’s Next? 104 13 Acknowledgements 106 2 | RESILIENT SEOUL | 3 01 MAYOR'S MESSAGE Park Won Soon Mayor of Seoul More than half of the world’s population resides in natural and social disasters and foster the capacity to urban areas. Not limited to just people, major infra- recover quickly in times of crisis. In 2013, Seoul took structure, including the economy, culture, transporta- part in the Making Cities Resilient campaign of the A Strategy tion, education, and health, are also densely located UNISDR. -

The Effect of a Special Interest Group on Apartment Price Collusion 1

The Effect of a Special Interest Group on Apartment Price Collusion 1 Eun Pyo Hong * This paper examines the effect of collusion by a special interest group (Association of the Resident Housewives, ARH) in the apart- ment market between 2006 and 2007 in Korea. Using the Difference- In-Difference (DID) design and carefully matching the apartments, it is estimated that every instance of collusion results in an increase of from KRW 7.2 to 40.3 million in the apartment price. The amount of increase varies by districts and apartment unit characteristics. The result in this paper shows that the effects of collusion explain the cause of a rapid rise in the price of apartment between 2006 and 2007. This paper contributes to the collusion literature by closely examining how a special interest group (ARH) affects price through the collusion. Keywords: Apartment price, Collusion, Special interest group, Difference in Difference (DID), Bidding ring JEL Classification: C5, D4 I. Introduction In Korea, residential apartments are considered as an effective solution for providing housing in major metropolitan areas. Apartments do not only provide housing but further serve as symbol of wealth and social status as they are highly valuable assets, constituting the largest por- tion of a typical household’s wealth. Therefore, the price volatility of the apartments is a very serious concern for apartment residents. * Graduate Student, Department of Economics, Seoul National University, Shillim Dong, Seoul, 151-746 (E-mail) [email protected]. This work was supported by “The Second Stage of the Brain Korea 21 Department of Economics, Seoul National University” Project in 2011. -

The Politics of Struggle in a State–Civil Society Partnership: a Case Study of a South Korean Workfare Partnership Programme

The London School of Economics and Political Science The Politics of Struggle in a State–Civil Society Partnership: A Case Study of a South Korean Workfare Partnership Programme Suyoung Kim A thesis submitted to the Department of Social Policy of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, June 2011 1 Declaration of Authorship I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. (Some items have been removed from this electronic version of the thesis as the copyrights are owned by other organisations.) Suyoung Kim June 2011 2 Acknowledgements In the course of writing this thesis, I have had the privilege of receiving help from a legion of people. At the top of the list stands my most sincere gratitude to my academic supervisor, Professor Hartley Dean, who guided the whole journey of my research with his extensive theoretical knowledge and professional experiences in welfare rights field. -

A Study of Perceptions of How to Organize Local Government Multi-Lateral Cross- Boundary Collaboration

Title Page A Study of Perceptions of How to Organize Local Government Multi-Lateral Cross- Boundary Collaboration by Min Han Kim B.A. in Economics, Korea University, 2010 Master of Public Administration, Seoul National University, 2014 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Membership Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH GRADUATE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS This dissertation was presented by Min Han Kim It was defended on February 2, 2021 and approved by George W. Dougherty, Jr., Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs William N. Dunn, Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs Tobin Im, Professor, Graduate School of Public Administration, Seoul National University Dissertation Advisor: B. Guy Peters, Maurice Falk Professor of American Government, Department of Political Science ii Copyright © by Min Han Kim 2021 iii Abstract A Study of Perceptions of How to Organize Local Government Multi-Lateral Cross- Boundary Collaboration Min Han Kim University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation research is a study of subjectivity. That is, the purpose of this dissertation research is to better understand how South Korean local government officials perceive the current practice, future prospects, and potential avenues for development of multi-lateral cross-boundary collaboration among the governments that they work for. To this purpose, I first conduct literature review on cross-boundary intergovernmental organizations, both in the United States and in other countries. Then, I conduct literature review on regional intergovernmental organizations (RIGOs). -

Age Integration Aging Society ISSN 2586-5692(Online)

Quarterly Brief 1 Age Integration Aging Society ISSN 2586-5692(Online) The 6th issue Issue Date. 2019. 04.30 Publisher. Soondool Chung Ewha Institute for Age Integration Research / Room No. 504-1. SK Telecom Center. 52, Ewhayeodae-gil, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03760 / TEL.02.3277.2235 Issue report I Creating a physical environment for an aged society: Korea’s experience Eun-ha JEONG Team Manager, Research and Development Team Policy Research Department Seoul Welfare Foundation The most crucial contribution made by the Global Network of Age-friendly Cities and Communities, a World Health Organization (WHO) initiative launched in 2010, is the government- led endeavors on reminding the global community of the need to develop policies in preparation for an aged society. It is particularly notable that the initiative puts cities and communities as the main agent of policy-making, enabling substantial changes that are relevant to citizens on the ground. The eight domains of an age-friendly community under the initiative cover the aspects of physical living environment, such as outdoor spaces and facilities, transportation, and housing, along with the issues related to the physical environment. This feature helped policy-makers expand and diversify their areas of interest in their efforts to prepare for population aging. Given the limited mobility in an old age, the lives of elderly people largely revolve around their decades-long residence and their community. The local community is therefore the backbone of their social relationships, enabling interactions with residents of various age groups and assistance for one another. This warrants attention to local communities as a spatial scope of activity where older citizens lead their everyday lives while maintaining various forms of social bonds. -

Daycare Center Shortage Problem in Seoul, Korea I. Background II

GIS Project Daycare Center Shortage Problem in Seoul, Korea Inhee Lee 3141-4698-85 I. Background These days, daycare center shortage is a serious problem in Seoul, Korea. Seoul is a huge city whose population is over 10 million, but the number of daycare centers is not enough to satisfy the young parents who have kids of age 0 to 5. Some daycare centers are so popular that you should get on the waiting-list as soon as you give a birth to a baby. Recently, Seoul City announced that they will open 600 new public daycare centers within 2020 to reduce the shortage problem. The new daycare centers should be allocated effectively, considering the relevant factors such as the population of children by districts. In this project, each area’s level of demand for public daycare center will be analyzed. II. Gathering Data For this project, I collected data from different sources as shown in the Table 1. Type Name Source Shapefile Map of Seoul http://www.arcgis.com/ Shapefile Location of Daycare Center (2015) http://map.seoul.go.kr/ List and Capacity Excel File http://iseoul.seoul.go.kr of Daycare Center (2015) Population, Birthrate, and Average Excel File http://kosis.kr/ Income of Each District (2015) Excel File Area of Each District http://stat.seoul.go.kr/ Table 1. Used Data List Page 1 / 12 III. Process 1. Idea Flows Map 1. Location of Daycare Centers and the Buffers The Map 1 shows the location of daycare centers and the 400-meter buffers around them. There are three types of daycare center; public daycare centers (red points), private daycare centers (blue points), and the daycare centers operated by companies for their employees (black stars). -

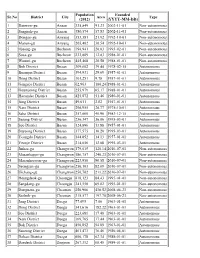

List of Districts of South Korea

Population Founded Sr.No District City Area Type (2012) (YYYY-MM-DD) 1 Danwon-gu Ansan 335,849 91.23 2002-11-01 Non-autonomous 2 Sangnok-gu Ansan 380,574 57.83 2002-11-01 Non-autonomous 3 Dongan-gu Anyang 353,381 21.92 1992-10-01 Non-autonomous 4 Manan-gu Anyang 265,462 36.54 1992-10-01 Non-autonomous 5 Ojeong-gu Bucheon 194,941 20.03 1993-02-01 Non-autonomous 6 Sosa-gu Bucheon 232,809 12.83 1988-01-01 Non-autonomous 7 Wonmi-gu Bucheon 445,468 20.58 1988-01-01 Non-autonomous 8 Buk District Busan 309,602 39.44 1978-02-15 Autonomous 9 Busanjin District Busan 394,931 29.69 1957-01-01 Autonomous 10 Dong District Busan 101,251 9.78 1957-01-01 Autonomous 11 Gangseo District Busan 62,963 180.24 1988-01-01 Autonomous 12 Geumjeong District Busan 255,979 65.17 1988-01-01 Autonomous 13 Haeundae District Busan 425,872 51.46 1980-01-01 Autonomous 14 Jung District Busan 49,011 2.82 1957-01-01 Autonomous 15 Nam District Busan 296,955 26.77 1975-10-01 Autonomous 16 Saha District Busan 357,060 40.96 1983-12-15 Autonomous 17 Sasang District Busan 256,347 36.06 1995-03-01 Autonomous 18 Seo District Busan 124,896 13.88 1957-01-01 Autonomous 19 Suyeong District Busan 177,575 10.20 1995-03-01 Autonomous 20 Yeongdo District Busan 144,852 14.13 1957-01-01 Autonomous 21 Yeonje District Busan 214,056 12.08 1995-03-01 Autonomous 22 Jinhae-gu Changwon 179,015 120.14 2010-07-01 Non-autonomous 23 Masanhappo-gu Changwon 186,757 240.23 2010-07-01 Non-autonomous 24 Masanhoewon-gu Changwon 223,956 90.58 2010-07-01 Non-autonomous 25 Seongsan-gu Changwon 250,103 82.09 2010-07-01 -

Overcoming the Not-In-My-Backyard Phenomenon in Waste Management

CASE STUDY November 2019 Overcoming the Not-in-My-Backyard Phenomenon in Waste Management: How Seoul Worked with a Citizens’ TABLE OF CONTENTS Opposition Movement and Built Executive Summary .............. 1 Incineration Facilities to Dispose of the Introduction ......................... 2 City’s Waste, 1991–2013 Delivery Challenges .............. 3 Tracing the Implementation Process .................................. 3 PROJECT DATA Lessons Learned ................... 8 ORGANIZATION: COUNTRY: Seoul Metropolitan Government Republic of Korea References ........................... 9 ORGANIZATION TYPE: REGION: City government East Asia DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGE: PROJECT DURATION: Waste management 1991–2013 DELIVERY CHALLENGES: AUTHOR Stakeholder Engagement, Opposition or Ahram Han Lack of Consensus SECTOR: Environment Executive Summary Proper waste disposal is difficult, especially when no one wants disposal facilities in his or her neighborhood. A sound waste management plan has to consider both environmental sustainability and the wishes of the local community. In Seoul’s case, it took two decades of efforts to develop consensus on building and operating incinerators in the Republic of Korea’s capital city to dispose of residents’ waste. City officials held hundreds of open discussions to provide information on waste disposal and to listen to local residents’ concerns. Incorporating citizens’ demands, the government introduced stringent standards for pollutant emissions and related control systems, and it provided compensation to residents in the affected residential areas. At the same time that it built incinerators to dispose of the city’s trash, the government introduced new energy and recycling policies that made energy production more efficient and reduced waste generation. Those policies made residents’ heating and electricity bills more affordable and reduced the total amount of waste the city had to dispose of. -

BTㆍGTㆍNT INDUSTRY in SEOUL SEOUL METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT BTㆍGTㆍNT INDUSTRY in SEOUL SEOUL METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT Contents

ENGLISH BTㆍGTㆍNT INDUSTRY IN SEOUL SEOUL METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT BTㆍGTㆍNT INDUSTRY IN SEOUL SEOUL METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT Contents BTㆍGTㆍNT INDUSTRY IN SEOUL BT Industry 06 GT Industry 32 Incentives for the BTㆍNTㆍGT Industry 50 SEOUL METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT The Global Biotechnology Industry 07 Global GT Industry 33 Tax Reduction/Exemption for BT GT Foreign-Invested Companies 51 Overview of the Korean Biotechnology Industry 09 Korea’s GT Industry 34 Market Size by Sector 11 Industry Trend 35 Major Industry’s Market Trend 12 GT Fields Given Priority by the INVEST 56 Seoul Metropolitan Government 39 Foreign Investment Process Industry Outlook and Investments 14 Business Activities of Foreign Foreign Investment in GT Industry 39 57 BT Labor Force 16 Companies in Korea Magok District 40 Government Support 17 Foreign Direct Investment Process 58 Competition 18 Nano Industry 42 The Biotechnology Industry in Seoul 20 Foreign Investment Incentives 60 Korea’s Nano Industry 43 Seoul’s BT Strategy 21 NT Land Support 61 Seoul’s Nano Industry 44 Success Story : Novartis Korea 22 Tax Support 61 Government Support Policy 44 Labor Cost of BT Industry 23 Cash Grant 62 New Growth Engine Hope Fund 45 Distribution of Biotechnology Companies in Seoul 24 Other Support 62 Gongneung District 46 Digital Media City 25 Foreign Investment Incentives 63 Magok District 48 Magok District 27 Support Organizations 64 Industry Overview BT Industry The Global Biotechnology Industry SEOUL METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT SEOUL METROPOLITAN The global biotechnology market is expanding at a double-digit growth rate thanks to countries focusing their investments in biotechnology as the national strategic sector. This trend is expected to last for some time, as is continued growth with committed investments. -

Health Profile Ⅰ

Songpa District Health Profile Ⅰ. Introduction to Songpa District 1. History of Songpa District 2. Location and Climate 3. Population 4. Administrative Organization 5. Public Health Center Ⅱ. General Health Level 1. Mortality 2. Disease Development 3. Obesity 4. Health Concern 5. Other Health Problems Ⅲ. Health Awareness and Lifestyle 1. Smoking 2. Drinking 3. Diet 4. Weight Control 5. Exercise Ⅳ. Use of Medical Service 1. Patients with Chronic Disease 2. Medical Check-Up 3. Cancer Test Ⅴ. Physical and Social Environment 1. Physical Environment 2. Social and Economic Environment Ⅵ. Public Health and Medical Service 1. Medical Service 2. Public Health Center Ⅰ Introduction to Songpa District 1. History of Songpa District In old days, Songpa was the capital of Hanseong Baekje 2,000 years ago. In modern days, it proudly hosted the 1986 Asian Games and 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. Songpa is a good place to live where traditional and modern cultures harmoniously exist together. It is believed that the name of Songpa dates back to even before the Goryeo Dynasty and it means a hill with pine trees (Song means a pine tree and Pa means a hill). Due to its location along the Han River, Songpa was the place where Neolithic men lived in prehistoric age. Later, as an ancient nation was built, Songpa was a place for living for the people of Gojoseon and it was the capital of Baekje for about 493 years from the founder, King Onjo to 21st King Gaero. Jamsil is the name given by a command of King Sejong of the Chosun Dynasty. Mulberry trees were planted in current Jamsil area and called “Dongjamsil”.