Overcoming the Not-In-My-Backyard Phenomenon in Waste Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Construction of Hong-Dae Cultural District : Cultural Place, Cultural Policy and Cultural Politics

Universität Bielefeld Fakultät für Soziologie Construction of Hong-dae Cultural District : Cultural Place, Cultural Policy and Cultural Politics Dissertation Zur Erlangung eines Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Soziologie der Universität Bielefeld Mihye Cho 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Jörg Bergmann Bielefeld Juli 2007 ii Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Research Questions 4 1.2 Theoretical and Analytical Concepts of Research 9 1.3 Research Strategies 13 1.3.1 Research Phase 13 1.3.2 Data Collection Methods 14 1.3.3 Data Analysis 19 1.4 Structure of Research 22 Chapter 2 ‘Hong-dae Culture’ and Ambiguous Meanings of ‘the Cultural’ 23 2.1 Hong-dae Scene as Hong-dae Culture 25 2.2 Top 5 Sites as Representation of Hong-dae Culture 36 2.2.1 Site 1: Dance Clubs 37 2.2.2 Site 2: Live Clubs 47 2.2.3 Site 3: Street Hawkers 52 2.2.4 Site 4: Streets of Style 57 2.2.5 Site 5: Cafés and Restaurants 61 2.2.6 Creation of Hong-dae Culture through Discourse and Performance 65 2.3 Dualistic Approach of Authorities towards Hong-dae Culture 67 2.4 Concluding Remarks 75 Chapter 3 ‘Cultural District’ as a Transitional Cultural Policy in Paradigm Shift 76 3.1 Dispute over Cultural District in Hong-dae area 77 3.2 A Paradigm Shift in Korean Cultural Policy: from Preserving Culture to 79 Creating ‘the Cultural’ 3.3 Cultural District as a Transitional Cultural Policy 88 3.3.1 Terms and Objectives of Cultural District 88 3.3.2 Problematic Issues of Cultural District 93 3.4 Concluding Remarks 96 Chapter -

SOUTH KOREA – November 2020

SOUTH KOREA – November 2020 CONTENTS PROPERTY OWNERS GET BIG TAX SHOCK ............................................................................................................................. 1 GOV'T DAMPER ON FLAT PRICES KEEPS PUSHING THEM UP ...................................................................................................... 3 ______________________________________________________________________________ Property owners get big tax shock A 66-year-old man who lives in Mok-dong of Yangcheon District, western Seoul, was shocked recently after checking his comprehensive real estate tax bill. It was up sevenfold.He owns two apartments including his current residence. They were purchased using severance pay, with rent from the second unit to be used for living expenses. Last year, the bill was 100,000 won ($90) for comprehensive real estate tax. This year, it was 700,000 won. Next year, it will be about 1.5 million won. “Some people might say the amount is so little for me as a person who owns two apartments. However, I’m really confused now receiving the bill when I’m not earning any money at the moment,” Park said. “I want to sell one, but then I'll be obliged to pay a large amount of capital gains tax, and I would lose a way to make a living.” On Nov. 20, the National Tax Service started sending this year’s comprehensive real estate tax bills to homeowners. The homeowners can check the bills right away online, or they will receive the bills in the mail around Nov. 26. The comprehensive real estate tax is a national tax targeting expensive residential real estate and some kinds of land. It is separate from property taxes levied by local governments. Under the government’s comprehensive real estate tax regulation, the tax is levied yearly on June 1 on apartment whose government-assessed value exceeds 900 million won. -

The Republic of Korea

The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in the Republic of Korea Samsik Lee Ae Son Om Sung Min Kim Nanum Lee Institute of Aging Society, Hanyang University Seoul, Republic of Korea The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in the Republic of Korea This report is prepared with the cooperation of HelpAge International. To cite this report: Samsik Lee, Ae Son Om, Sung Min Kim, Nanum Lee (2020), The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in in the Republic of Korea, HelpAge International and Institute of Aging Society, Hanyang University, Seoul, ISBN: 979-11-973261-0-3 Contents Chapter 1 Context 01 1. COVID -19 situation and trends 1.1. Outbreak of COVID-19 1.2. Ruling on social distancing 1.3. Three waves of COVID-19 09 2. Economic trends 2.1. Gloomy economic outlook 2.2. Uncertain labour market 2.3. Deepening income equality 13 3. Social trends 3.1. ICT-based quarantine 3.2. Electronic entry 3.3. Non-contact socialization Chapter 2 Situation of older persons Chapter 3 Responses 16 1. Health and care 47 1. Response from government 1.1. COVID-19 among older persons 1.1. Key governmental structures Higher infection rate for the young, higher death rate for the elderly 1.2. COVID-19 health and safety Critical elderly patients out of hospital Total inspections Infection routes among the elderly Cohort isolation 1.2. Healthcare system and services 1.3. Programming and services Threat to primary health system Customized care services for senior citizens Socially distanced welfare facilities for elderly people Senior Citizens' Job Project Emergency care services Online exercise 1.3. -

Seoul IBX Data Center Seoul, South Korea [email protected]

IBX TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS Digital Media City 24 World cup buk-ro 60-gil SL1 Sangam-dong, Mapo-gu +82.2.6138.4511 (Sales) Seoul IBX Data Center Seoul, South Korea [email protected] EQUINIX SEOUL DATA CENTERS Equinix helps accelerate business performance by connecting ay ssw re p companies to their customers and partners inside the world’s most x Seongbuk-gu E u S N b networked data centers. When it opens later in 2019, the SL1 e ae o n g Jongno-gu ® a Equinix International Business Exchange™ (IBX ) will be our first m - ro data center in South Korea, one of the most digitally connected TY4SL1 W o ld countries in Asia. eu W Seodaemun-gu ke o o rl m d C -r up o B u k Located in the Mapo district of Seoul, SL1 will be in close proximity - ro to Seoul’s central business district and the Yeouido financial district, O Mapo-gu lym pic to provide 1,685m² (18,137ft²) of colocation space in Phase 1. -d Seoul a ® e G a bykeo Forming part of Platform Equinix , it will offer the products, services ro n g nb uk - r and solutions to deploy an Interconnection Oriented Architecture® o ® (IOA ) strategy and connect you to partners and customers in the Yongsan-gu capital city of South Korea, the 4th largest metropolitan economy y Yeongdeungpo-gu a globally, and in over 52 cities around the world. w s s re p x E SEOUL IBX® BENEFITS u b o • Strategic location near Seoul’s central business district and the e Dongjak-gu S Yeouido financial district • Our carrier-neutral data center will provide multiple network and cloud connectivity options • Connect to the digital ecosystem in Seoul, the 4th largest Seocho-gu metropolitan economy globally and the capital city of South Gwanak-gu Korea, one of the most digitally connected countries in Asia Equinix.com SL1 Seoul IBX Data Center IBX TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS Building Amenities Reliability Space • Break Room Our IBX data centers boast an Colocation Space Phase 1: 1,685 m2 (18,137 ft2) • Loaner Tools industry-leading, high average uptime • Work Kiosks track record of >99.9999% globally. -

Focusing on the Street Quarter of Mapo-Ro in Seoul Young-Jin

Urbanities, Vol. 8 · No 2· November 2018 © 2018 Urbanities High-rise Buildings and Social Inequality: Focusing on the Street Quarter of Mapo-ro in Seoul Young-Jin Kim (Sungshin University, South Korea) [email protected] In this article I discuss the cause and the effects of the increase in high-rise buildings in the ‘street quarter’ of Mapo-ro in Seoul, South Korea. First, I draw on official reports and Seoul Downtown Redevelopment Master Plans to explore why this phenomenon has occurred. Second, I investigate the sociocultural effects of high-rise buildings using evidence collected through an application of participant observation, that is, a new walking method for the study of urban street spaces. I suggest that the Seoul government’s implementation of deregulation and benefits for developers to facilitate redevelopment in downtown Seoul has resulted in the increase of high-rise buildings. The analysis also demonstrates that this increase has contributed to gentrification and has led to the growth of private gated spaces and of the distance between private and public spaces. Key words: High-rise buildings, residential and commercial buildings, walking, Seoul, Mapo-ro, state-led gentrification. Introduction1 First, I wish to say how this study began. In the spring of 2017, a candlelight rally was held every weekend in Gwanghwamun square in Seoul to demand the impeachment of the President of South Korea. On 17th February, a parade was added to the candlelight rally. That day I took photographs of the march and, as the march was going through Mapo-ro,2 I was presented with an amazing landscape filled with high-rise buildings. -

Making Cities More Livable: the Korean Model Workshop on Smart City in Environment, Equity, and Economy (3Es)

Knowledge Series No. 11 Making Cities More Livable: The Korean Model Workshop on Smart City in Environment, Equity, and Economy (3Es) 28-31 October 2019 Seoul, Republic of South Korea Knowledge Series No. 11 Making Cities More Livable Co-Organized by the Digital Technology for Development Unit, Seoul, Republic of South Korea Sustainable Development and Climate Change Department, 28-31 October 2019 Asian Development Bank; and Seoul Housing & Communities Corporation Contents 01 Workshop Overview 02 Programme 05 Opening Remarks INTEGRATED URBAN PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT 06 Managing City Growth 10 Site Visit : Magok District (Seoul Botanic Park) 11 Site Visit : Seoul Housing Lab ENVIRONMENTALLY SUSTAINABLE CITY 12 City Development and River 14 Site Visit : Han River Ferry Cruise 16 Environment and Waste Management 18 Site Visit : Bakdal Wastewater Treatment Plant 19 Site Visit : Mapo Resource Recovery Facility URBAN TRANSPORTATION FOR INCLUSIVE CITY 20 Urban Development and Transportation 24 Site Visit : Transport Operation and Information Service (TOPIS) Center COMPETITIVE CITY 26 Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Startup Support Programs 28 Site Visit: Seoul Start Up Hub 29 Site Visit: KU Anam-dong Campus Town 30 E-Government and Smart Administration 32 Group Discussions and Presentations Knowledge Series No. 11 Workshop Overview ities in Asia and the Pacific have unprecedented Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) Strategy 2030 Copportunities to transform human well-being and identified “Making Cities More Livable” as one of its catalyze economic development by 2030. At the same seven operational priorities and will support cities in time, these cities face several mega trends, including developing member countries (DMCs) for developing high rates of urbanization, growing infrastructure the right institutions, policies, and enabling environment deficits, increasing risks of climate change impacts and to become more livable. -

Resilient Seoul

SEOUL A Strategy for Urban Resilience 2019 RESILIENT 2019 RESILIENT SEOUL | A Strategy for Urban Resilience 2019 Smart Safe City for All, Seoul A Strategy for Urban Resilience 2019 3 | RESILIENT SEOUL | 1 Photo by An Yeon-soo CONTENTS 01 Introduction 04 02 Executive Summary 08 03 What is Urban Resilience? 10 04 Introducing Seoul 12 05 Seoul in Context 18 06 Seoul’s History of Disasters 20 07 Journey Towards Resilient Seoul 22 08 100RC Network 36 09 Goal 1 Governance- Resilience through Collaboration 38 A Program 1. Safety Governance Strategy Program 2. Smart Safety Net for Program 3. Climate Change Response System Urban Program 4. Proactive Management for Aging Infrastructure Resilience Program 5. Safer Neighborhoods 2019 10 Goal 2 Community- Stronger and Connected Community 66 Program 6. Connected Neighborhood for the Vulnerable Program 7. Stable and Affordable Housing for All Program 8. Childbirth and Childcare Service Program 9. Innovative Solutions in Community 11 Goal 3 Inclusive Growth- Prosperous Seoul for All 80 Program 10. Youth Welfare and Jobs Program 11. Employment Opportunities for the Elderly Program 12. Microbusiness and the Self-employed Program 13. Respect for Labor Program 14. Expansion of Social Economy 12 What’s Next? 104 13 Acknowledgements 106 2 | RESILIENT SEOUL | 3 01 MAYOR'S MESSAGE Park Won Soon Mayor of Seoul More than half of the world’s population resides in natural and social disasters and foster the capacity to urban areas. Not limited to just people, major infra- recover quickly in times of crisis. In 2013, Seoul took structure, including the economy, culture, transporta- part in the Making Cities Resilient campaign of the A Strategy tion, education, and health, are also densely located UNISDR. -

The Effect of a Special Interest Group on Apartment Price Collusion 1

The Effect of a Special Interest Group on Apartment Price Collusion 1 Eun Pyo Hong * This paper examines the effect of collusion by a special interest group (Association of the Resident Housewives, ARH) in the apart- ment market between 2006 and 2007 in Korea. Using the Difference- In-Difference (DID) design and carefully matching the apartments, it is estimated that every instance of collusion results in an increase of from KRW 7.2 to 40.3 million in the apartment price. The amount of increase varies by districts and apartment unit characteristics. The result in this paper shows that the effects of collusion explain the cause of a rapid rise in the price of apartment between 2006 and 2007. This paper contributes to the collusion literature by closely examining how a special interest group (ARH) affects price through the collusion. Keywords: Apartment price, Collusion, Special interest group, Difference in Difference (DID), Bidding ring JEL Classification: C5, D4 I. Introduction In Korea, residential apartments are considered as an effective solution for providing housing in major metropolitan areas. Apartments do not only provide housing but further serve as symbol of wealth and social status as they are highly valuable assets, constituting the largest por- tion of a typical household’s wealth. Therefore, the price volatility of the apartments is a very serious concern for apartment residents. * Graduate Student, Department of Economics, Seoul National University, Shillim Dong, Seoul, 151-746 (E-mail) [email protected]. This work was supported by “The Second Stage of the Brain Korea 21 Department of Economics, Seoul National University” Project in 2011. -

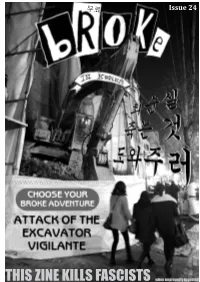

THIS ZINE KILLS FASCISTS When Improperly Ingested Letter from the Editor Table of Contents Well That Took a While

무료 Issue 24 THIS ZINE KILLS FASCISTS when improperly ingested Letter from the Editor Table of Contents Well that took a while. I’ve concluded it’s hard to motivate myself to 1. Cover write zines while I’m also working at a newspaper. Even if it’s “that” newspaper, it still lets me print a lot of crazy stuff, at least until I start 2. This Page pushing it too far. Issue 24 The last issue was starting to seem a little lazy, as I was recycling con- 3. Letters to the Editor June/Sept 2017 tent also published in the newspaper. For this issue I wanted to cut down on that, as well as on lengthy interviews. So we have a lot of smaller 4. Ash stories, and all sorts of other quick content. I interviewed a lot of people This zine has been published and sliced up their interviews into pieces here and there. I also filched a 5. Dead Gakkahs at random intervals for the lot of content from social media, mainly as PSAs. Think of it more as a past ten years. social media share/retweet, but on paper; hope no one’s pissed. 6. Pseudo & BurnBurnBurn There’s a page spread on Yuppie Killer memories I solicited way back Founders when Yuppie Killer had their last show. There’s also a similar spread on 7. WDI & SHARP Jon Twitch people’s memories of Hongdae Playground, where you can get a sense 8. Playground Paul Mutts of how radically the place has changed, as well as possibly the effect we had on it ourselves. -

Mapo-Gu 3153-9217 - Purchase PP Gunny Bags at the Stores Where You Can Buy Garbage Bags

Foreigner Registration The Discharge of Recycling Waste Large-sized Waste - Visit the Community Center : Report at the Community Center and pay the charges > Get the Information on Standard Plastic Garbage Bags Registration period : Within 90 days from the entry date, at the time when a foreigner acquires the The Discharge Way of Recycling Waste sticker > Discharge with the sticker H residence qualification or the change permission of residence qualification - Discharge in front of the house and store at the designated day after putting a recycling waste in - On-line Application : Web-site for big-sized waste(www.mapo.go.kr/bigclean) >On-line application Purchase and Management of Standard Plastic Garbage Bag Required Documents : Foreigner registration form, Passport, Picture 1(3x4cm), Attached Hospital Address Specialty Foreign Language Business Hours the clear plastic bag (not in the black plastic bag) without foreign substances >Payment >Output the discharge sticker >Discharge with the sticker - You should purchase the standard garbage bags at designated stores. When you move to other No. Tel. Note. documents by residence qualifications Name (Location details) Day Night Day time Night time Weekday Saturday - If it is discharged not in the accordance with the rules, it will be get the pick-up refusal sticker and When report the discharge, it must be correctly filled in the place and date of discharge. areas, you can return the garbage bags to the place of purchase. Fees: 10,000 Won (Government revenue stamp) The Disposal of Small Construction Waste less than 5 Tons Sinchon Rotary Subway Orthopedics, Orthopedics, not be collected. Waste available for recycling : Sinchon Recycling Center 713-7289 Sinchon No. -

Community-Based Care for Older Persons Implications from China, Korea and Vietnam

Community-based Care for Older Persons Implications from China, Korea and Vietnam The Sasakawa Peace Foundation Community-based Care for Older Persons Implications from China, South Korea, and Vietnam Community-based Care for Older Persons: Implications from China, Korea, and Vietnam Published in 2019 by The Sasakawa Peace Foundation The Sasakawa Peace Foundation Bldg. 1-15-16 Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8524, Japan Phone: +81-3-5157-5430 Fax: +81-3-5157-5420 URL: https://www.spf.org/ All rights reserved Copyrights © The Sasakawa Peace Foundation Table of Contents Table of Contents Foreword ....................................................................................................................................v Preface and Acknowledgements .............................................................................................vi Introduction ...............................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Informal Care Program in Shanghai, China ........................................................7 1. Case 1: Si Tang Jian .............................................................................................................7 1.1. Background .................................................................................................................7 1.2. The Government-subsidized Si Tang Jian in Dongfeng-cun .......................................9 1.3. Privately-sector-assisted Si Tang Jian in Lvqiao-cun ...............................................12 -

The Politics of Struggle in a State–Civil Society Partnership: a Case Study of a South Korean Workfare Partnership Programme

The London School of Economics and Political Science The Politics of Struggle in a State–Civil Society Partnership: A Case Study of a South Korean Workfare Partnership Programme Suyoung Kim A thesis submitted to the Department of Social Policy of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, June 2011 1 Declaration of Authorship I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. (Some items have been removed from this electronic version of the thesis as the copyrights are owned by other organisations.) Suyoung Kim June 2011 2 Acknowledgements In the course of writing this thesis, I have had the privilege of receiving help from a legion of people. At the top of the list stands my most sincere gratitude to my academic supervisor, Professor Hartley Dean, who guided the whole journey of my research with his extensive theoretical knowledge and professional experiences in welfare rights field.