Conservation Prioritization KKMEZW “Middle” Islands Conservation Prioritization KKMEZW “Middle” Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tongass National Forest Roadless Rule Complaint

Katharine S. Glover (Alaska Bar No. 0606033) Eric P. Jorgensen (Alaska Bar No. 8904010) EARTHJUSTICE 325 Fourth Street Juneau, AK 99801 907.586.2751; [email protected]; [email protected] Nathaniel S.W. Lawrence (Wash. Bar No. 30847) (pro hac vice pending) NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL 3723 Holiday Drive, SE Olympia, WA 98501 360.534.9900; [email protected] Garett R. Rose (D.C. Bar No. 1023909) (pro hac vice pending) NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL 1152 15th St. NW Washington DC 20005 202.289.6868; [email protected] Attorneys for Plaintiffs Organized Village of Kake, et al. IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF ALASKA ORGANIZED VILLAGE OF KAKE; ORGANIZED VILLAGE OF ) SAXMAN; HOONAH INDIAN ASSOCIATION; KETCHIKAN ) INDIAN COMMUNITY; KLAWOCK COOPERATIVE ) ASSOCIATION; WOMEN’S EARTH AND CLIMATE ACTION ) Case No. 1:20-cv- NETWORK; THE BOAT COMPANY; UNCRUISE; ALASKA ) ________ LONGLINE FISHERMEN’S ASSOCIATION; SOUTHEAST ) ALASKA CONSERVATION COUNCIL; NATURAL RESOURCES ) DEFENSE COUNCIL; ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS; ) ALASKA WILDERNESS LEAGUE; SIERRA CLUB; DEFENDERS ) OF WILDLIFE; NATIONAL AUDUBON SOCIETY; CENTER FOR ) BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY; FRIENDS OF THE EARTH; THE ) WILDERNESS SOCIETY; GREENPEACE, INC.; NATIONAL ) WILDLIFE FEDERATION; and ENVIRONMENT AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) v. ) ) SONNY PERDUE, in his official capacity as Secretary of ) Agriculture, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ) AGRICULTURE, STEPHEN CENSKY, or his successor, in his ) official capacity as Deputy Secretary of Agriculture; and UNITED ) STATES FOREST SERVICE, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF (5 U.S.C. §§ 701-706; 16 U.S.C. § 551; 16 U.S.C. § 1608; 42 U.S.C. § 4332; 16 U.S.C. § 3120) INTRODUCTION 1. This action challenges a rule, 36 C.F.R. -

Annual Report of Survey-Inventory Activities 1 July 1988-30 June 1989 .....ELK

Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Annual Report of Survey-Inventory Activities 1 July 1988-30 June 1989 .....ELK- Compiled and edited by Sid 0. Morsan, Publications Technician Vol XX, Part ill Project W-23-2, Study 13.0 May 1990 STATE OF ALASKA Steve Cowper, Governor DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Don W. Collinsworth, Commissioner DIVISION OF WILDLIFE CONSERVATION W. Lewis Pamplin, Jr., Director W. Bruce Dinneford, Acting Planning Chief Persons intending to cite this material should obtain prior permis sion from the author(s) and/or the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Because most reports deal with preliminary results of conti nuing studies, conclusions are tentative and should be identified as such. Due credit will be appreciated. Additional copies of this report, or reports on other species covered in this series may be obtained from: Publications Technician ADF&G, Wildlife Conservation P.O. Box 3-2000 Juneau, AK 99802 (907) 465-4190 The Alaska Department of Fish & Game operates all of its public pro grams and activities free from discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, or handicap. Because the department receives federal funding, any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against should write to: O.E.O., U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. 20240. TABLE OF CONTENTS .. ) Game Management Unit Map. • . • . • • .I . • ii Statewide Harvest and Population status • .iii Game Management Unit/Geographical Description GMU 3 - Islands of the Petersburg, Wrangell, and Kake areas • . • . • • . 1 GMU 8 - Kodiak, Afognak, and adjacent islands. -

Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission

SALMON-TAGGING EXPERIMENTS IN ALASKA, 1924 AND 1925 1 .:I- By WILLIS H. RICH, Ph. D. Director, U. S. Biological Station, Seattle, Wash; .:I CONTENTS Page Introduction _ 109 Experiments in southeastern Alaska__hhu u __nn_h__u u u _ 116 Tagging record _ 116 Returns from experiments in Icy Strait__ n h_u u_..u u _ 119 Returns from experiments in Frederick Sound u huh _ 123 Returns from experiments in Chatham Strait; h u • _ 123 Returns from experiments in Sumner Strait, u_uuu .. u _ 128 Returns from experiments at Cape Muzon and Kaigani Point, ~ _ 135 Returns from experiments at Cape Chacon u n u h _ 137 Returns from experiments near Cape Fox and Duke Islandu _ 141 Variations in returns of tagged fish; h _u u n n h n __ h u_ 143 Conelusions _ 144 Experiments at Port Moller, 1925un__h_uu uu __ 145 INTRODUCTION The extensive salmon-tagging experiments conducted during 1922 and 1923 2 in the region of the Alaska Peninsula proved so productive of information, both of scientific interest and of practical application in the care of these fisheries, that it was considered desirable to undertake similar investigations in other districts; Accordingly, experiments were carried on in southeastern Alaska in 1924 and again in 1925. In 1925, also, at the request of one of the companies engaged in packing salmon in the Port Moller district, along the northern shore of the Alaska Penin sula, the work done there in 1922 was repeated. The results of these experiments form the basis for the following report. -

Southeast Alaska Mid-Region Access Port and Ferry Terminal Technical Memorandum

S A M-R A P Ferr T T M Prepared for Fr Highw An Through R Pecci Associates, I. 825 Custer Avenue Helena, Montana 59604 (406)447-5000 www.rpa-hln.com Prepared by T Gos Associates, I. 1201 Western Avenue, Suite 200 Seattle, WA 98101 www.glosten.com Pametri, I. 700 NE Multnomah, Suite 1000 Portland, OR 97232-4110 T. 503.233.2400 F, 503.233.4825 www.parametrix.com CITATION The Glosten Associates, Inc., Parametrix, Inc. 2011. Southeast Alaska Mid-Region Access Port and Ferry Terminal Technical Memorandum. Prepared by The Glosten Associates, Inc., Seattle, Washington, Parametrix, Inc., Portland, Oregon. April 2011. Port and Ferry Terminal Technical Memorandum TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... ES-1 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Purpose of the Mid-Region Access Study ......................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Southeast Alaska Mid-Region Access Study Corridors ..................................................... 1-3 1.2.1 Bradfield Canal Corridor ....................................................................................... 1-3 1.2.2 Stikine River Corridor ........................................................................................... 1-5 1.2.3 Aaron Creek Corridor............................................................................................ 1-5 1.3 Characteristics -

Kupreanof / Mitkof Province

Kupreanof / Mitkof Province and northeastern Kupreanof. In the southwestern corner fringing Rocky Pass, extensive volcanic rocks underlie a rolling, boggy plateau. Other portions of the province have greater relief, but only in the northwest corner are there highly productive parent materials that once supported extensive large-tree forest. Mitkof Island has the northernmost redcedars on the archipelago. (A few occur to the north at Farragut Bay on the mainland.) Yellow-cedars are abundant throughout the province, yet a large proportion of cedar stands are currently experiencing a systematic die-off that is wide-spread throughout Southeast Alaska and northern British Columbia (Hennon et al. 1990, Hennon et al. 2005). Compared to island provinces such as East Chichagof and North Prince of Wales, where deeply dissecting fiords and more rugged relief create obstacles to wildlife connectivity, Kupreanof-Mitkof Province has a low degree of natural fragmentation. This province has a high number of mammal species; collectively, Kupreanof and Mitkof host 21 known mammal species, the second largest number (after Wrangell/Etolin) for any island province (MacDonald FIG 1. Kupreanof-Mitkof Province. and Cook 1999). This species richness certainly reflects proximity to the Stikine River which is a major The biogeographic province of Kupreanof and Mitkof corridor connecting wildlife from the interior with the Islands is located in central Southeast north of the coastal forests. Stikine River Delta (Fig 1). This province has one of Kake and Petersburg–the province’s two mid-sized the highest proportions (65%) of development lands of communities– are both dependent upon the any province in Southeast and only 5% of the lands are surrounding marine and terrestrial environment. -

Alaska's Marine Highway Corridor Management Plan

ALASKAíS MARINE HIGHWAY CORRIDOR PARTNERSHIP PLAN Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the Nation’s Most Scenic Byway. Prepared for The Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities, as part of the submission materials required for the designation under the National Scenic Byways Program of the Federal Highway Administration Prepared by Jensen Yorba Lott, Inc. February 2002 With Whiteman and Taintor Christianson Communications, Inc. Assistance from Walsh Services Southeast Strategies The McDowell Group Gateway Technologies Alaskaís Marine Highway Corridor Partnership Plan January 22, 2002 Dear Reader, It is with great pleasure I endorse the proposal to Southcentral Alaska, as well as along the far-flung chain connections will be improved, allowing designate Alaska’s Marine Highway as a National of Aleutian Islands. It is a story about people who have recreational enthusiasts to go directly from ships Scenic Byway. One travel writer summed up the thrived for generations upon the richest landscape— to footpaths, to port communities, to hiking great power of Alaska’s Marine Highway this way: Native Alaskans, Russian settlers, Scandinavian trails, to other scenic byways, and beyond. “one of the world’s most scenic highways requires no fishermen, soldiers, miners, and timber harvesters. It is driving, no road maps, no expensive stops at the gas a story about marine and upland wildlife—humpback In 2003, Alaska’s Marine Highway turns 40 years station, and no automobile.” and killer whales, seals and sea lions, sea otters, salmon old. In honor of this milestone, the State of and a myriad of exotic fish, teeming colonies of Alaska is nominating the Marine Highway for As a water-based highway, Alaska’s Marine Highway seabirds, bears, deer, moose and wolves. -

Clarence Leroy Andrews Books and Papers in the Sheldon Jackson Archives and Manuscript Collection

Clarence Leroy Andrews Books and Papers in the Sheldon Jackson Archives and Manuscript Collection ERRATA: based on an inventory of the collection August-November, 2013 Page 2. Insert ANDR I RUSS I JX238 I F82S. Add note: "The full record for this item is on page 108." Page6. ANDR I RUSS I V46 /V.3 - ANDR-11. Add note: "This is a small booklet inserted inside the front cover of ANDR-10. No separate barcode." Page 31. ANDR IF I 89S I GS. Add note: "The spine label on this item is ANDR IF I 89S I 84 (not GS)." Page S7. ANDR IF I 912 I Y9 I 88. Add note: "The spine label on this item is ANDR IF/ 931 I 88." Page 61. Insert ANDR IF I 931 I 88. Add note: "See ANDR IF I 912 I Y9 I 88. Page 77. ANDR I GI 6SO I 182S I 84. Change the date in the catalog record to 1831. It is not 1931. Page 100. ANDR I HJ I 664S I A2. Add note to v.1: "A" number in book is A-2S2, not A-717. Page 103. ANDR I JK / 86S. Add note to 194S pt. 2: "A" number in book is A-338, not A-348. Page 10S. ANDR I JK I 9S03 I A3 I 19SO. Add note: "A" number in book is A-1299, not A-1229. (A-1229 is ANDR I PS/ S71 / A4 I L4.) Page 108. ANDR I RUSS I JX I 238 / F82S. Add note: "This is a RUSS collection item and belongs on page 2." Page 1SS. -

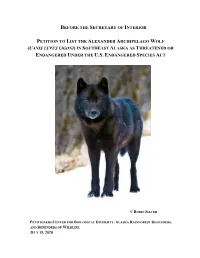

Petition to List the Alexander Archipelago Wolf in Southeast

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE ALEXANDER ARCHIPELAGO WOLF (CANIS LUPUS LIGONI) IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © ROBIN SILVER PETITIONERS CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS, AND DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE JULY 15, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Siekaniec, Alaska Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road Anchorage, AK 99503 [email protected] PETITIONERS Shaye Wolf, Ph.D. Larry Edwards Center for Biological Diversity Alaska Rainforest Defenders 1212 Broadway P.O. Box 6064 Oakland, California 94612 Sitka, Alaska 99835 (415) 385-5746 (907) 772-4403 [email protected] [email protected] Randi Spivak Patrick Lavin, J.D. Public Lands Program Director Defenders of Wildlife Center for Biological Diversity 441 W. 5th Avenue, Suite 302 (310) 779-4894 Anchorage, AK 99501 [email protected] (907) 276-9410 [email protected] _________________________ Date this 15 day of July 2020 2 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Alaska Rainforest Defenders, and Defenders of Wildlife petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”), to list the Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) in Southeast Alaska as a threatened or endangered species. -

Alaska Resources Library & Information Services Anr

Nl? 1- li4S~ FIELD INVESTIGATIONS OF THE HERPETOLOGICAL TAXA IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA , Bradford R. Norman1 and Thomas J. Hassler National Biological Service California Cooperative Fishery Research Unit Humboldt State University Arcata, California 95521 FINAL REPORT 29-95 ARLIS Alaska Resources Library & Information Services Anr.honu1f' Al~~k::l 1Present address: 3390 William Street, Eureka, California 95503 2 ABSTRACT Herpetological investigations were conducted at 285 transects from 28 March through 31 September 1992 in southeast Alaska. Key museum collections were examined and a complete review of the state of Alaskan herpetological literature was undertaken. The 1992 vouchers were inventoried and analyzed from 1993 through 1995. Several thousand individual specimen observations of six amphibian species were tabulated. The six herpetological species encountered in 1992 were: rough-skinned newt (Tariaha granulosa), western toad (Bufo boreas), long-toed salamander (Ambystoma maarodaatylum), spotted frog (Rana pretiosa), wood frog (R. sylvatiaa), and Pacific chorus frog (Pseudacris regilla). In many cases combinations of these species were found to breed sympatrically (i.e., at the same location and concurrently over the period of observations). Special attempts to trap and/or observe various additional herpetological taxa were made but with negative results. The herpetological species which were specifically searched for but which were not encountered were: the Alaskan slender salamander (Batraahoseps caudatus), northwestern salamander (Ambystoma gracile), Pacific giant salamanders (genus Diaamptodon), tailed frog (Asaaphus truei), Siberian salamanders (genus Hynobius), garter snakes (Thamnophis spp.), and sea turtles (Families: Cheloniidae and Dermochelyidae). The presence of garter snakes in the state of Alaska could not be verified during this study though considerable effort was put forth to this end. -

By S.M. Karl and R.D. Koch

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP MF-197C C U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAPS AND PRELIMINARY INTERPRETATION OF ANOMALOUS ROCK GEOCHEMICAL DATA FROM THE PETERSBURG QUADRANGLE, AND PARTS OF THE PORT ALEXANDER, SITKA, AND SUMDUM QUADRANGLES, SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA By S.M. Karl and R.D. Koch INTRODUCTION flysch, volcanic rocks, and melange that includes fault- bounded blocks of older sedimentary and volcanic rocks. Statistical analyses of minor- and trace-element The eastern part of the study area comprises the geochemical data for 6,974 rock samples from the Mainland belt of Brew and others (1984), which include" Petersburg quadrangle and minor parts of the Port the Taku and Tracy Arm terranes of Berg and others Alexander, Sitka, and Sumdum quadrangles (hereafter (1978). According to Brew and others (1984), rocks of referred to as the Petersburg study area) identified 887 the Taku and Tracy Arm terranes may include samples with anomalously high concentrations of one or metamorphosed equivalents of the Alexander terrane more elements. This report includes a list of the 887 rocks. The country rocks of the Mainland belt increase samples (table 1), histograms showing the distribution of in metamorphic grade from west to east, to as high as chemical values (see fig. 2), a brief description of the amphibolite facies, and are intruded by various igneous geologic context and distribution of the samples, a map components of the Coast plutonic-metamorphic complex of bedrock geochemical groups (sheet 1), and 12 maps of Brew and Ford (1984) (sheet 1). showing the locations of samples that have anomalous The Coast plutonic-metamorphic complex includes amounts of precious metals, base metals, and selected rare the metamorphosed equivalents of the Paleozoic and metals (sheets 2-7). -

Petersburg Borough Comprehensive Plan Update

PETERSBURG BOROUGH COMPREHENSIVE PLAN UPDATE February 22, 2016 Prepared by Agnew::Beck Consulting, Moffat and Nichol, and Northern Economics for the Petersburg Borough this page left intentionally blank ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Listed below are the many individuals, groups and organizations that have contributed to the Petersburg Borough comprehensive planning update process, beginning in the fall of 2014. THANK YOU for contributing your valuable time, knowledge of your community, the Borough, the region, and most of all, for your creative and innovative ideas on how Petersburg Borough can continue to be a great place to live, grow up, raise a family, start and own a business, build a career, and recreate. Your commitment to this process, including subsequent prioritization and implementation of key strategies and actions, is the key to the success of the plan, and the ultimate goal of sustaining the Borough by strategically building and expanding upon everything that makes Petersburg Borough great. Also – if we forgot someone in the list below, our apologies. We had so much great feedback from so many folks that we may have missed a name or two. Thank you, too! Petersburg Borough Residents – thanks to everyone that participated in the community survey, attended a planning event/meeting and/or shared your feedback in some other format. The Petersburg Borough Assembly • Mark Jensen, Mayor • Cindi Lagoudakis, Vice Mayor • Bob Lynn • Jeigh Stanton Gregor • John Havrilek (former) • Kurt Wohlhueter • Nancy Strand • Eric Castro The Petersburg Borough -

Important Bird Areas in Southeastern Alaska

Important Bird Areas in Southeastern Alaska Iain J. Stenhouse As the U.S. Partner for BirdLife International, a sites in their communities. To date, 46 states have global coalition of more than 100 organizations, the initiated IBA programs and more than 1,800 IBAs National Audubon Society is working to identify a have already been identified in the U.S. network of sites that provide critical habitat for birds. This effort, known as the Important Bird QUALIFICATION AS AN IBA Areas (or IBA) Program, recognizes that habitat loss IBAs are sites that provide essential habitat for and fragmentation are the most serious threats facing one or more bird species. They include sites for populations of birds across North America and breeding, wintering, and/or migrating, and range around the world. By working through partnerships, from sites of a few hundred acres to hundreds of principally the North American Bird Conservation thousands of acres. They are usually discrete sites Initiative (NABCI), to identify those places that are that stand out from the surrounding landscape, they critical to birds during some part of their life cycle, may include public or private lands, or both, and we hope to minimize the effects that habitat they may be protected or unprotected. degradation and loss have on bird populations. The To qualify as an IBA, a site must satisfy at least IBA program is a global effort to identify areas that one of the following criteria. The site must support: are most important for maintaining bird populations • species of conservation concern (species and focus conservation efforts at protecting these already considered threatened or endangered); sites.