The Art of Kiki Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to the Secretary-General Tonight You and Mrs. Annan Have

Note to the Secretary-General Tonight you and Mrs. Annan have agreed to drop by (from 6:35-6:45 p.m.) the reception in the West Terrace hosted by Yoko Ono wherein she will present grants to an Israeli and a Palestinian artist in her own Middle East humanitarian arts initiative. When Mrs. Annan and you arrive David Finn, Philippa Polskin and Holly Peppe of Ruder-Finn, will greet you. You will then be accompanied into the center of the room where two easels will display the work of the two artist recipients of the LennonOno Grants, Khalil Rabah and Zvi Goldstein. The following people will greet you and stand with you for a brief photo-op: > Yoko Ono > Zvi Goldstein, Israeli artist, grant recipient > Khalil Rabah, Palestinian artist, grant recipient > Jack Persekian, Founder & Director, Anadiel Gallery, Jerusalem > Suzanne Landau, Chief Curator, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem > Shlomit Shaked, Independent Curator, Israel. At 6:45 p.m. you will proceed to the Macalester Reception and dinner, in Private Dining Room #8. Kevin S.: 9 October 2002 Copy to: Ms. S. Burnheim ROUTING SLIP FICHE DE TRANSMISSION TO: A A: OJ *Mt* FROM: / /" DE: /64< ^*^/^^~^ Room No. — No de bureau Extension — Poste Date / G&W aiLbfo^ FOR ACTION POUR SUITE A DONNER FOR APPROVAL POUR APPROBATION FOR SIGNATURE POUR SIGNATURE FOR COMMENTS POUR OBSERVATIONS MAY WE DISCUSS? POURRIONS-NOUS EN PARLER ? YOUR ATTENTION VOTRE ATTENTION AS DISCUSSED COMME CONVENU AS REQUESTED SUITE A VOTRE DEMANDS NOTE AND RETURN NOTER ET RETOURNER FOR INFORMATION POUR INFORMATION COM.6 12-78) ZVI GOLDSTEIN Artist Recipient of the LennonOno Grant for Peace Born in Transylvania, Romania in 1947, artist Zvi Goldstein immigrated to Israel in 1958. -

Kiki Smith : Natural Etchings [Text Byjudith B

Kiki Smith : natural etchings [text byJudith B. Hecker] Author Smith, Kiki, 1954- Date 2003 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Prints and Illustrated Books Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/133 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art Kiki Smith Natura I Etchings In the second half of the 1990s the focus of Kiki Smith's Smith's first etchings of animals were based on printmaking shifted from the human body to the bodies museum specimens and are characterized by simple of birds and animals, and to exploring humanity's rela linearity and powerful morbidity, as in the multipart tionship with other earthly creatures. She often sketched etchings Destruction of Birds (1997, dated 1998) and directly from dead and stuffed specimens (some deli White Mammals (1998), where the bodies seem to berately sought out in natural history museums, some dangle in the space of each sheet. She then moved on encountered in ordinary life), depicting them isolated on to more richly described representations. To achieve blank backgrounds that directed attention to their form the detail and realism of Fawn (2001), Smith built up and symbolic resonance rather than to their environ the image slowly on the metal etching plate, gradually ment. Her regard for the life of animals was matched developing the varying textures of the animal's fur, the by an appreciation of the aesthetic qualities of their tufts on its chest, and the position of its limbs. -

Press Release Kiki Smith. Hearing You with My Eyes 9.10.2020 – 10.1.2021

Page 1 of 16 Press release Lausanne, 8 October 2020 Kiki Smith. Hearing You with My Eyes (9.10.2020 – 10.1.2021) Kiki Smith. Hearing You with My Eyes 9.10.2020 – 10.1.2021 Contents 1. Press release 2. Media photographs 3. Artist’s biography 4. Excerpts from the catalogue 5. Public engagement– Public outreach services 6. Museum services: Book and Giftshop, Le Nabi Café-restaurant 7. MCBA Partners and sponsors Contact: Aline Guberan Communication and marketing manager 079 179 91 03 [email protected] Florence Dizdari Press coordinator 079 232 40 06 [email protected] Page 2 of 16 Press release Lausanne, 8 October 2020 Kiki Smith. Hearing You with My Eyes (9.10.2020 – 10.1.2021) 1. Press release Exploring the body and the senses: a major Swiss show on the work of Kiki Smith The work of the American artist Kiki Smith is the featured subject of a major temporary show this fall at the MCBA Musée cantonal des Beaux- Arts of Lausanne. Boasting a selection of nearly one hundred works, some of which are on display for the very first time in Europe, this survey covers almost four decades of artmaking, focusing on a theme that is central to her output yet has been little explored until now, i.e., sensory perception. Devoted to the work of Kiki Smith (born 1954), the show Hearing You with My Eyes is a rare opportunity for the general public to get to know the major themes that run through the American artist’s output, themes that spring from her observation of the human body. -

Feminist Perspectives on Curating

Feminist perspectives on curating Book or Report Section Published Version Richter, D. (2016) Feminist perspectives on curating. In: Richter, D., Krasny, E. and Perry, L. (eds.) Curating in Feminist Thought. On-Curating, Zurich, pp. 64-76. ISBN 9781532873386 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/74722/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.on-curating.org/issue-29.html#.Wm8P9a5l-Uk Publisher: On-Curating All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online ONN CURATING.org Issue 29 / May 2016 Notes on Curating, freely distributed, non-commercial Curating in Feminist Thought WWithith CContributionsontributions bbyy NNanneanne BBuurmanuurman LLauraaura CastagniniCastagnini SSusanneusanne ClausenClausen LLinaina DzuverovicDzuverovic VVictoriaictoria HorneHorne AAmeliamelia JJonesones EElkelke KKrasnyrasny KKirstenirsten LLloydloyd MMichaelaichaela MMeliánelián GGabrielleabrielle MMoseroser HHeikeeike MMunderunder LLaraara PPerryerry HHelenaelena RReckitteckitt MMauraaura RReillyeilly IIrenerene RevellRevell JJennyenny RichardsRichards DDorotheeorothee RichterRichter HHilaryilary RRobinsonobinson SStellatella RRolligollig JJulianeuliane SaupeSaupe SSigridigrid SSchadechade CCatherineatherine SSpencerpencer Szuper Gallery, I will survive, film still, single-channel video, 7:55 min. Contents 02 82 Editorial It’s Time for Action! Elke Krasny, Lara Perry, Dorothee Richter Heike Munder 05 91 Feminist Subjects versus Feminist Effects: Public Service Announcement: The Curating of Feminist Art On the Viewer’s Rolein Curatorial Production (or is it the Feminist Curating of Art?) Lara Perry Amelia Jones 96 22 Curatorial Materialism. -

Pop up 1 Montauk Final

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Prentice Art Communications 212.228.4048 [email protected] Fabiola Beracasa and Art Production Fund In association with Gary Carrion-Murayari and Joyce Sitterly present Pop Up 1: Montauk August 1 – September 8, 2013 (Montauk, NY) – Fabiola Beracasa and Art Production Fund, in association with Gary Carrion-Murayari and Joyce Sitterly of the New Museum, are pleased to present Pop Up 1: Montauk, an outdoor pop-up exhibition featuring site- specific installations by artists Anya Kielar, Virginia Overton, and Olympia Scarry. On view from August 1 to September 8, 2013, the exhibition will be located on an undeveloped lot at 333 Old Montauk Highway. It will be open to the public Thursday-Sunday from 12-6 p.m. and by appointment on the remaining weekdays. A public opening reception for the artists will be held on August 1 from 6-8p.m. "By commissioning three emerging contemporary artists to engage with the site and local community, we aim to honor Montauk's artistic legacy and continue its fertile cultural dialogue," said gallerist Fabiola Beracasa. Anya Kielar will present a series of new fabric paintings made of gauze, tulle, and ripped canvas that will hang from clothing lines installed on the lot. Envisioned by the artist as a mise-en-scène, the transparent paintings feature stylized portraits of women and encourage viewer interaction. The outdoor site prompted Kielar to incorporate elements of nature in her production process, including a sun printing technique used to weather the fabric. Virginia Overton will produce a new sculptural piece conceived specifically for the Old Montauk Highway site. -

HIRSHHORN MUSEUM and SCULPTURE GARDEN LIBRARY VIDEO COLLECTION Recordings May Not Be Usable in Current Format

HIRSHHORN MUSEUM AND SCULPTURE GARDEN LIBRARY VIDEO COLLECTION Recordings may not be usable in current format. Check with Library staff. Video materials are not circulated. (updated August 26, 2008) VHS TAPES 1. 41-10 Mr. & Mrs. Chagall, daughter, son-in-law 2. 74-60 HMSG Opening Ceremonies 3. 74-90 Visit of architect Gordon Bunshaft 4. 74-210 Hirshhorn Museum dedication ceremony 5. 75-00 Hirshhorn: Man and Museum-Camera 3 6. 76-20 A life of its own, v-1 7. 79-50 John Baldessari 8. 87-20 Mark Di Suvero: Storm King 9. 88-20 “Cornered” video Installation (Adrian piper piece) 10. 89-20 Buster Simpson (HMSG) 11. 90-30 Scenes and Songs from Boyd Webb (video documentary) 12. 92-80 Robert Irwin- In response 13. 93-20 Paul Reed Catalog #9-1936-1992 (artists’ work) 14. 93-30 Collection that Became a Museum (Smithsonian Film Transfer) 15. 93-30 Collection that Became a Museum (copy) 16. 93-50 A life of its own 17. 93-50 A life of its own 1976 18. 96-20 Thomas Eakins and the Swimming Picture 19. 96-60 Beverly Semmes 20. 97-10 Judith Zilczer interview on De Kooning 21. 97-80 Jeff Wall segment 22. 97-100 Willem De Kooning 23. 98-10 George Segal (HMSG) 24. 98-20 George Segal-Dialogue (HMSG) 25. 00-30 The Ephemeral is Eternal (De Stijl play) 26. 00-40 Gary Hill- Dig 27. 00-60 Willem De Kooning 28. 00-100 The collection that became a Museum-Ron J. Cavalier (HMSG) 29. 1974 Visit of Architect Bunshaft (HMSG) 30. -

William Gropper's

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2014 Volume 3, Number 6 Artists Against Racism and the War, 1968 • Blacklisted: William Gropper • AIDS Activism and the Geldzahler Portfolio Zarina: Paper and Partition • Social Paper • Hieronymus Cock • Prix de Print • Directory 2014 • ≤100 • News New lithographs by Charles Arnoldi Jesse (2013). Five-color lithograph, 13 ¾ x 12 inches, edition of 20. see more new lithographs by Arnoldi at tamarind.unm.edu March – April 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Fierce Barbarians Associate Publisher Miguel de Baca 4 Julie Bernatz The Geldzahler Portfoio as AIDS Activism Managing Editor John Murphy 10 Dana Johnson Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios Makeda Best 15 News Editor Twenty-Five Artists Against Racism Isabella Kendrick and the War, 1968 Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Shaurya Kumar 20 Zarina: Paper and Partition Online Columnist Jessica Cochran & Melissa Potter 25 Sarah Kirk Hanley Papermaking and Social Action Design Director Prix de Print, No. 4 26 Skip Langer Richard H. Axsom Annu Vertanen: Breathing Touch Editorial Associate Michael Ferut Treasures from the Vault 28 Rowan Bain Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad Reviews Britany Salsbury 30 Programs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre Kate McCrickard 33 Hieronymus Cock Aux Quatre Vents Alexandra Onuf 36 Hieronymus Cock: The Renaissance Reconceived Jill Bugajski 40 The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda Sarah Andress 42 Nicola López: Big Eye Susan Tallman 43 Jane Hammond: Snapshot Odyssey On the Cover: Annu Vertanen, detail of Breathing Touch (2012–13), woodcut on Maru Rojas 44 multiple sheets of machine-made Kozo papers, Peter Blake: Found Art: Eggs Unique image. -

Untitled (Forever), 2017

PUBLISHERS DISTRIBUTED BY D.A.P. SP21 CATALOG CAPTIONS PAGE 6: Georgia O’Keeffe, Series I—No. 3, 1918. Oil on Actes Sud | Archive of Modern Conflict | Arquine | Art / Books | Art Gallery of York board, 20 × 16”. Milwaukee Art Museum. Gift of Jane University | Art Insights | Art Issues Press | Artspace Books | Aspen Art Museum | Atelier Bradley Pettit Foundation and the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. PAGE 7: Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Mesa Éditions | Atlas Press | August Editions | Badlands Unlimited | Berkeley Art Museum | Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II, 1930. Oil on canvas. 24.5 x 36”. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Gift Blank Forms | Bokförlaget Stolpe | Bywater Bros. Editions | Cabinet | Cahiers d’Art of the Burnett Foundation. PAGE 8: (Upper) Emil Bisttram, | Canada | Candela Books | Carnegie Museum Of Art | Carpenter Center | Center For Creative Forces, 1936. Oil on canvas, 36 x 27”. Private collection, Courtesy Aaron Payne Fine Art, Santa Fe. Art, Design and Visual Culture, UMBC | Chris Boot | Circle Books | Contemporary Art (Lower) Raymond Jonson, Casein Tempera No. 1, 1939. Casein on canvas, 22 x 35”. Albuquerque Museum, gift Museum, Houston | Contemporary Art Museum, St Louis | Cooper-Hewitt | Corraini of Rose Silva and Evelyn Gutierrez. PAGE 9: (Upper) The Editions | DABA Press | Damiani | Dancing Foxes Press | Deitch Projects Archive | Sun, c. 1955. Oil on board, 6.2 × 5.5”. Private collection. © Estate of Leonora Carrington. PAGE 10: (Upper left) DelMonico Books | Design Museum | Deste Foundation for Contemporary Art | Dia Hayao Miyazaki, [Woman] imageboard, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). © Studio Ghibli. (Upper right) Center For The Arts | Dis Voir, Editions | Drawing Center | Dumont | Dung Beetle | Hayao Miyazaki, [Castle in the Sky] imageboard, Castle Dust to Digital | Eakins Press | Ediciones Poligrafa | Edition Patrick Frey | Editions in the Sky (1986). -

De Biënnale Van Venetië Een Handleiding Op Sneakers

De Biënnale van Venetië Een handleiding op sneakers. Door Chantal Pattyn. Alles voor de kunst Van maandag tot donderdag om 17u THE SUMMER OF LOVE AND ART 2017 is een historisch jaar voor de beeldende kunst. Na een proloog in Athene (nog tot 16 juli) vindt in Kassel de vijfjaarlijkse Documenta plaats. Op een steenworp daarvandaan, in Münster, is er Skulptur Projekte, dat slechts om de tien jaar wordt georganiseerd en deze keer in handen is van de oude en wijze curator Kasper König. Maar om de twee jaar trekken wij trouw naar de grand old lady aller tentoonstellingen: La Biennale di Venezia. De Dogen- stad kreunt dan nog meer dan anders onder het gewicht van de kunst, met naast de Biënna- le zelf tal van tentoonstellingen, zoals van Damien Hirst, Philip Guston en Shirin Neshat. De Belgen zijn alvast goed vertegenwoordigd. Dirk Braeckman toont zijn sublieme foto’s in het Belgisch Paviljoen. Koen Vanmechelen steelt de show aan het Canal Grande met een bronzen kippenpoot en twee gigantische eieren. Jan Fabre is present met Glass and Bone Sculptures. Edith Dekyndt is met prachtig werk vertegenwoordigd op Viva Arte Viva. Axel Vervoordt pakt voor de laatste keer het Palazzo Fortuny in met de innemende tentoonstelling Intuition. Geen mens die het allemaal bekeken kan krijgen, maar voor uw mentaal comfort, alsmede antici- perend op zere voeten en een hoofd dat van al die beelden zeer explosief kan worden, lijst ik een paar persoonlijke hoogtepunten op. De Biënnale vindt traditioneel plaats in de Giardini, het mooie park van Venetië. In het Cen- trale Paviljoen kan je het eerste deel van de grote tentoonstelling bekijken. -

DAVID WOJNAROWICZ (1954–1992) B

DAVID WOJNAROWICZ (1954–1992) b. 1954, Red Bank, NJ d. 1992, New York, NY SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 I is Someone Else, Morán Morán, Los Angeles CA David Wojnarowicz, Photography & Film, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC 2019 History Keeps Me Awake at Night, Museum Reina Sofia, Madrid David Wojnarowicz, Photography & Film, Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2018 History Keeps Me Awake at Night, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY Soon All This Will be Picturesque Ruins: The Installations of David Wojnarowicz, P·P·O·W, New York, NY David Wojnarowicz: Video and Photography, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany. David Wojnarowicz: Flesh of My Flesh, Iceberg Projects, Chicago, IL 2016 Raging Through: The Art of David Wojnarowicz, Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 2011 Spirituality, P·P·O·W, New York, NY 2009 David Wojnarowicz, Supportico Lopez, Berlin, Germany 2006 Rimbaud in New York, CABINET, London, England David Wojnarowicz, Between Bridges, London, England 2004 Out of Silence: Artworks with Original Text by David Wojnarowicz, P·P·O·W, New York, NY David Wojnarowicz: Rimbaud in New York, Roth Horowitz Gallery, New York, NY Close Up sur David Wojnarowicz, Forum des Halles Espace Rencontres, Paris, France 2001 Featured Works VI: David Wojnarowicz: The Elements, Fire and Water, Earth and Wind, Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, IL 1999 Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz, New Museum, New York, NY David Wojnarowicz: The Boys Go Off -

Aarhus Commissions Book

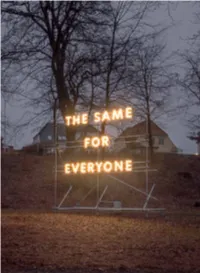

2 3 Commissions: European Capital of Culture Aarhus 2017 4 5 Contents 177 LIST with Hideyuki Nakayama Architecture and Matilde Cassani Harbour Magnets 193 Chunky Move Depth of Field — Aarhus Variation 19 Foreword 205 Mikhail Karikis Rebecca Matthews The Chalk Factory 22 Introduction 221 Maria Hassabi Juliana Engberg STAGING - undressed 39 Nathan Coley 235 Berlinde De Bruyckere THE SAME FOR EVERYONE Embalmed - Twins, 2017 57 Barbara Kruger 251 Ulla Von Brandenburg Untitled (Never Enough) It Has A Golden Sun And An Elderly Grey Moon 71 Jenny Holzer 269 Angelica Mesiti For Aarhus Mother Tongue 87 Jasmina Cibic 288 Artist Biographies & Acknowledgements A Shining City on a Hill 300 Writer Biographies 109 Wayne McGregor LightLens 301 Aarhus 2017 Acknowledgements 125 Anohni with Kembra Pfahler and Johanna Constantine 302 Public Partners Future Feminism 303 Foundations, International Commissioning Partners & Sponsors 141 Public Movement Rescue (2017) 304 Members of the Board in 2017 153 Eglè Budvytytè 305 Aarhus 2017 Team in 2017 Shakers, Lovers and Bystanders 306 Project Teams 167 Callum Morton Sisyphus 308 Images Foreword Rebecca Matthews - CEO In an amazing year of programme highlights, we are delighted to bring together in this book some of the outstanding visual and performing art commissions created for European Capital of Culture Aarhus 2017. We have invited writers to make interpreta- tions of the works so that the ideas and imaginings of our guest artists can travel even further and live into future times. Through the vision of artists we are able to see our special year as relevant and meaningful in many ways. These projects read the mood of now, a time in which we ask pertinent questions about our European context, our shared sense of community and those things that bind and challenge us. -

Kiki Smith Biography

Kiki Smith Biography Kiki Smith was born in 1954 in Nuremberg, Germany, before her family moved to the United States in 1955. The daughter of the American actress and opera singer Jane Lawrence and the architect, painter and Abstract Expressionist sculptor Tony Smith (1912–1980), she grew up in an artistic environment which informed her sense of possibility. Virtually self-taught, Smith describes herself as a “thing-maker." In the 1970s she was drawn to representational art because when she moved to New York at that time many artists were interested in figuration. Around 1978, she joined Collaborative Projects, Inc. (Colab), an artists' collective devoted to making art accessible through exhibitions outside commercial gallery settings. It was during this period that she made her first artworks, monotypes and drawings of everyday objects. Kiki Smith's works explore emotional states such as fear and dissonance as well as existential responses to being in the world. Her attention to themes of death and mortality evolved from her own life experience. Her father died in 1980 and in the late 1980s, Kiki Smith's younger sister died from an AIDS-related illness, along with many of her colleagues from the art community. Kiki Smith had her first solo exhibition in 1988 at the Fawbush Gallery in New York, and her first one-person museum show in 1989 at the Dallas Museum of Art, followed by her first European exhibition at the Centre d'art Contemporain in Geneva in 1990. In 1991, she was included in the Whitney Biennial in New York for the first time.